Home : Travel : Berlin and Prague : Part 4

Despite only having scratched the surface of an enigmatic city, I

decided to move south to Prague by train, which is a wonderfully romantic

journey. For about an hour one rolls through Eastern German

countryside that might best be described as "Midwestern flat." In

these first weeks of spring, the fields were green or carpeted with

yellow flowers and many trees sported lovely white blossoms. The main

difference from the U.S. was the absence of modern cars and farm

equipment. Also the houses are rather old, brown, and decrepit.

Rolling into Dresden was fascinating. Berlin, especially West Berlin,

doesn't have large barren spaces and haphazard redevelopment. It is

therefore a bit tough to imagine how thoroughly the city was bombed.

Dresden, however, still looks like a wasteland with a few restored or

at least remaining houses separated by large empty spaces. Some of

those spaces are punctuated by tall plain apartment or office

buildings, but the overall effect looks neither charming nor

planned.

After bomb-scarred Dresden, the storybook valley of the Elbe was

particularly beguiling. Our train traveled up this river for about

three hours. The German side is studded with fine old houses and

occasional towns nestled into side canyons. The walls of the valley

are often quite steep, with sheer rock faces 75m high in some places.

Eastern Germans bicycled along the road on the other bank and the

river was ever so flat and lazy. Once we got to the Czech Republic,

the river became much more industrial and houses lost their charm.

After bomb-scarred Dresden, the storybook valley of the Elbe was

particularly beguiling. Our train traveled up this river for about

three hours. The German side is studded with fine old houses and

occasional towns nestled into side canyons. The walls of the valley

are often quite steep, with sheer rock faces 75m high in some places.

Eastern Germans bicycled along the road on the other bank and the

river was ever so flat and lazy. Once we got to the Czech Republic,

the river became much more industrial and houses lost their charm.

Germany is great preparation for Prague. First, although the Czechs heartily dislike Germans, one often encounters waitresses who speak German but not English (I was glad for once that I hadn't learned German too well; my accent and mistakes were a plus here). Second, the filthy cars and cigarette smoke in Germany toughened up my lungs for the even filthier cars driven by the Czechs. Third, German officialdom takes itself so seriously that the Czechs seem positively Italian by comparison. Fourth, the aggressive German drivers cushioned the blow of arriving in a city where the speed limit is 100 kph on all streets after 11:00 pm.

Germany is great preparation for Prague. First, although the Czechs heartily dislike Germans, one often encounters waitresses who speak German but not English (I was glad for once that I hadn't learned German too well; my accent and mistakes were a plus here). Second, the filthy cars and cigarette smoke in Germany toughened up my lungs for the even filthier cars driven by the Czechs. Third, German officialdom takes itself so seriously that the Czechs seem positively Italian by comparison. Fourth, the aggressive German drivers cushioned the blow of arriving in a city where the speed limit is 100 kph on all streets after 11:00 pm.

A quick walk along the Vltava or Moldau (yes, the same river that inspired Smetana) bewitched me with unexpected beauty at every corner. A lot of unmarked buildings here have more grace to them than all of the tourist sights in Berlin combined. Furthermore, the whole atmosphere of the city is light. One sees lovers embracing and people eating on the streets, rare sights indeed in Berlin. London and Paris are wonderful, of course, but 95% of the people one sees in those cities are rushing off to do something productive. It always makes me feel lazy after a few days. In the center of Prague, however, one sees mostly tourists or very relaxed locals.

A quick walk along the Vltava or Moldau (yes, the same river that inspired Smetana) bewitched me with unexpected beauty at every corner. A lot of unmarked buildings here have more grace to them than all of the tourist sights in Berlin combined. Furthermore, the whole atmosphere of the city is light. One sees lovers embracing and people eating on the streets, rare sights indeed in Berlin. London and Paris are wonderful, of course, but 95% of the people one sees in those cities are rushing off to do something productive. It always makes me feel lazy after a few days. In the center of Prague, however, one sees mostly tourists or very relaxed locals.

Upon reaching the famous Karlov Most (Charles Bridge), I knew that I'd

found tourist heaven. Visa cash advances, pizza, guidebooks, sketch

artists, schlock artists, money changers, all open for business on a

Sunday evening. The medieval bridge is reserved for pedestrians and

is thronged with deadbeats from many nations. They strum their

guitars and sing Czech and American folk music. Imagine Harvard

Square on steroids.

Upon reaching the famous Karlov Most (Charles Bridge), I knew that I'd

found tourist heaven. Visa cash advances, pizza, guidebooks, sketch

artists, schlock artists, money changers, all open for business on a

Sunday evening. The medieval bridge is reserved for pedestrians and

is thronged with deadbeats from many nations. They strum their

guitars and sing Czech and American folk music. Imagine Harvard

Square on steroids.

After a couple of hours in Prague, I'd already noticed what every other male tourist had: Czech women are stunning. They tend to be tall, blond, slender, have interesting features, and are a bit proud and aloof. They won't boldly meet your eye like women in France or Italy, but it would be unfair to call them cold. In fact, the unhappiest person in Prague is probably an ambassador who shall remain nameless. He's single. He's got the mansion, he's got the servants, he's got the big car. His misfortune is that the country he represents might be embarrassed if he were seen running around town with any of the locals. Anyway, you won't forget that Paulina Porizikova is Czech; every tenth woman here might be her sister.

All alone in Prague, I really appreciated how easy it was to meet people, especially other tourists. Everyone is relaxed and at his or her best. On my first evening stroll, I met two Czechs, seven Americans, and a smattering of Europeans. This is the world's best city for practicing languages. In just one day, I spoke English to the Dutch tourists, French to the French, German to get food, Italian to the Italians, even a bit of Hebrew to an Israeli and a few words of Japanese to a couple of stunned Osakans.

Despite spending most of my time socializing, I managed to see a lot of Prague's tourist treasures on my very first day. Praguers were early Protestants and prone to hurling Catholic officials out of windows or off of bridges. The Jesuits were sent in to awe and threaten the citizens back to Catholicism and dotted the city with Baroque splendors such as St. Nicholas. This church would have kept Moses busy for awhile; huge golden idols hover above each chapel and graven images cover the walls.

Despite spending most of my time socializing, I managed to see a lot of Prague's tourist treasures on my very first day. Praguers were early Protestants and prone to hurling Catholic officials out of windows or off of bridges. The Jesuits were sent in to awe and threaten the citizens back to Catholicism and dotted the city with Baroque splendors such as St. Nicholas. This church would have kept Moses busy for awhile; huge golden idols hover above each chapel and graven images cover the walls.

As I walked up to the renowned Prague Castle, from which Václav Havel continues a centuries-old tradition of Czech governance, the guard was changing with a flourish of brass. The castle is a collection of walled-in buildings on top of a hill, the most notable of which is St. Vitus Cathedral. My second favorite feature of the cathedral is an Art Nouveau stained glass window that was even financed by an insurance company and shows the psalm "Those who Sow in Tears Shall Reap in Joy."

As I walked up to the renowned Prague Castle, from which Václav Havel continues a centuries-old tradition of Czech governance, the guard was changing with a flourish of brass. The castle is a collection of walled-in buildings on top of a hill, the most notable of which is St. Vitus Cathedral. My second favorite feature of the cathedral is an Art Nouveau stained glass window that was even financed by an insurance company and shows the psalm "Those who Sow in Tears Shall Reap in Joy."

My favorite part of the cathedral was something I'd have missed completely without the Cadogan guide: St. John Nepomuk's tongue. John was hurled into the river in 1383 for appointing an abbot against King Wenceslas IV's wishes. Three centuries later the Jesuits were casting about for a Prague-base saint and invented the following tale: that the King had demanded John relate what the Queen had confessed to him, and that John went to his death rather than betray her confidence. In 1715 a canonization committee exhumed John's body and found that his tongue was "throbbing with life" and still growing; he was canonized in 1729. Although there are numerous parts of dead people that are available for worship around Prague, the tongue was removed in the 1980's after further examination revealed that it was in fact a desiccated brain. John has a 1700 kg (as much as a full-size Chevrolet) solid silver tomb with beautiful Baroque figures of angels surrounding the swooning saint.

My favorite part of the cathedral was something I'd have missed completely without the Cadogan guide: St. John Nepomuk's tongue. John was hurled into the river in 1383 for appointing an abbot against King Wenceslas IV's wishes. Three centuries later the Jesuits were casting about for a Prague-base saint and invented the following tale: that the King had demanded John relate what the Queen had confessed to him, and that John went to his death rather than betray her confidence. In 1715 a canonization committee exhumed John's body and found that his tongue was "throbbing with life" and still growing; he was canonized in 1729. Although there are numerous parts of dead people that are available for worship around Prague, the tongue was removed in the 1980's after further examination revealed that it was in fact a desiccated brain. John has a 1700 kg (as much as a full-size Chevrolet) solid silver tomb with beautiful Baroque figures of angels surrounding the swooning saint.

One of the biggest draws of the Prague castle is the Golden Lane,

lined with tiny colorful houses. They didn't do much for me, not even

one where Kafka lived for four months (he spent his whole life in

Prague so that practically every other building has some Kafka story).

The house was rented by his sister Ottla, who was exempted from

wartime anti-Jewish laws because of her German husband. After her

sisters and their husbands were hauled off to the Lodz ghetto, she

became less sold on Aryan culture and divorced her husband. Ottla was

sent first to Theresienstadt, then volunteered to escort a children's

train to Auschwitz where she died.

One of the biggest draws of the Prague castle is the Golden Lane,

lined with tiny colorful houses. They didn't do much for me, not even

one where Kafka lived for four months (he spent his whole life in

Prague so that practically every other building has some Kafka story).

The house was rented by his sister Ottla, who was exempted from

wartime anti-Jewish laws because of her German husband. After her

sisters and their husbands were hauled off to the Lodz ghetto, she

became less sold on Aryan culture and divorced her husband. Ottla was

sent first to Theresienstadt, then volunteered to escort a children's

train to Auschwitz where she died.

I walked down the hill to the Old Town Square--armed with my

Cadogan guide to Prague--and found it rich in history. Here was the

balcony from which the communist state was announced and then cheered

every year thereafter, there was the place where Protestant nobles

were beheaded, along the east edge was the church where Tycho Brahe is

entombed. The square looks peaceful today, but it has been the site

of numerous bloodbaths. The most recent was May 8, 1945, a week after

Hitler's suicide and the same day people in Paris and New York were

celebrating V-E day. Prague was actually the last European

battlefield of WWII. Three days earlier, Prague had risen against the

Nazis and, in part of a battle that left 5000 Czechs dead, the Germans

obliterated one wing of the town hall with a tank. It was two more

days before the Russians liberated the town (US forces could have

gotten there earlier, but stood idle so as not to breach the Yalta

agreement).

I walked down the hill to the Old Town Square--armed with my

Cadogan guide to Prague--and found it rich in history. Here was the

balcony from which the communist state was announced and then cheered

every year thereafter, there was the place where Protestant nobles

were beheaded, along the east edge was the church where Tycho Brahe is

entombed. The square looks peaceful today, but it has been the site

of numerous bloodbaths. The most recent was May 8, 1945, a week after

Hitler's suicide and the same day people in Paris and New York were

celebrating V-E day. Prague was actually the last European

battlefield of WWII. Three days earlier, Prague had risen against the

Nazis and, in part of a battle that left 5000 Czechs dead, the Germans

obliterated one wing of the town hall with a tank. It was two more

days before the Russians liberated the town (US forces could have

gotten there earlier, but stood idle so as not to breach the Yalta

agreement).

My next stop was the old Jewish quarter containing a few remains of a

community dating back at least to the 10th century. Jews were spread

out on both sides of the river originally, but in 1179 the Church

announced that Christians should avoid contact with Jews, by either

moating or walling them in. Jews were locked in at night and all

through Easter/Passover. Despite some pogroms and banishments, the

Prague ghetto was a center of mysticism and Jewish thought. In 1784,

Emperor Joseph II opened the ghetto and Jews with money or ability

moved out (much as middle class blacks abandoned U.S. inner cities in

the 1960's, leaving them today with just half their 1960 population).

The ghetto became a sparsely-inhabited slum and nearly all the old

buildings were razed to make room for broad streets and Art Nouveau

buildings. Only six synagogues, the town hall, and a cemetery were

spared and these ended up being selected by Hitler for a postwar

"Exotic Museum of an Extinct Race."

Everyone had told me how great the cemetery was, with its tombstones

practically piled on top of one another. Consequently, it was a

disappointment. Not only did it look just as I'd imagined, but it was

packed with Italian and French tourists. Unlike the Germans, the

Czechs have developed their Jewish quarter into a major tourist

attraction and the resulting lack of solitude inhibits quiet

reflection.

Everyone had told me how great the cemetery was, with its tombstones

practically piled on top of one another. Consequently, it was a

disappointment. Not only did it look just as I'd imagined, but it was

packed with Italian and French tourists. Unlike the Germans, the

Czechs have developed their Jewish quarter into a major tourist

attraction and the resulting lack of solitude inhibits quiet

reflection.

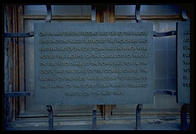

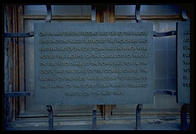

Within the cemetery is the Pinkasova synagogue. After the war, someone painted the walls with the names, birthdates, and deathdates of the 77,297 Czech Jews killed by the Germans. The Communists didn't take very good care of Hitler's Jewish museum and this synagogue was no exception. After the Yom Kippur War, they ripped out the names and even installed some anti-Israel exhibits in this area. Artists are currently painstaking painting the names back in.

Within the cemetery is the Pinkasova synagogue. After the war, someone painted the walls with the names, birthdates, and deathdates of the 77,297 Czech Jews killed by the Germans. The Communists didn't take very good care of Hitler's Jewish museum and this synagogue was no exception. After the Yom Kippur War, they ripped out the names and even installed some anti-Israel exhibits in this area. Artists are currently painstaking painting the names back in.

Although I didn't see the museum containing exhibits of children's art from concentration camps (it was closed for "technical reasons"--this is a popular expression in Prague museumdom but I never figured out what it meant), the Nazi collection of Jewish stuff from all over Europe was nothing to write home about. Let's face it: the prohibition on idolatry and the sheer poverty of European Jewry prevented them from ever making anything very interesting.

In the evening, I met Rebecca, Becky, Michelle, and Angela (all Americans flexing their Delta Airlines employee benefits) at a marionette version of Don Giovanni. This combines two big Prague traditions: Don Giovanni, which was premiered here, and puppetry. It was fun if you knew the story well and didn't mind expressions that were, well, wooden. Being in the company of four attractive women wasn't bad either, although Rebecca was just recovering from having her wallet stolen (this is a familiar lament among Prague tourists).

I spent the next day lazily roaming through Prague's innumerable parks

and gardens and ended up back at the castle. My favorite part of the

castle is the window from which two Catholic officials were hurled by

angry noblemen. The Church maintains that the Virgin Mary came down

with wings and flew them to safety; eyewitnesses say that they landed

in a dungheap. I had a long conversation with a 50ish Czechwoman in

the tourist information office. She was sick and tired of people

confusing her wonderfully advanced country with such backwaters as

Poland. In fact, she maintained that Czechs were better educated in

science and technology than Americans. I conceded that their subways

I spent the next day lazily roaming through Prague's innumerable parks

and gardens and ended up back at the castle. My favorite part of the

castle is the window from which two Catholic officials were hurled by

angry noblemen. The Church maintains that the Virgin Mary came down

with wings and flew them to safety; eyewitnesses say that they landed

in a dungheap. I had a long conversation with a 50ish Czechwoman in

the tourist information office. She was sick and tired of people

confusing her wonderfully advanced country with such backwaters as

Poland. In fact, she maintained that Czechs were better educated in

science and technology than Americans. I conceded that their subways

and trams were

remarkably efficient, but honesty

compelled me to note the unfortunate resemblance between Czech cars

and American lawnmowers.

and trams were

remarkably efficient, but honesty

compelled me to note the unfortunate resemblance between Czech cars

and American lawnmowers.

My next encounter was with 25 Italian schoolgirls on their senior trip

abroad. You don't know the meaning of exuberance until you've met 25

18-year-old girls who are thrilled to discover that an American speaks

their language. They surrounded me and my head was spinning from

trying to remember my Italian, remember their names, and look at them

all at once.

In the evening, I had dinner with Yves, Fanny and Corinne, three refined Bretons. Fanny and Corinne pretended to consider our opinion, but it was clear which sex was going to choose the restaurant. They picked an established place that was actually listed in their guidebook. Such places generally have the rude service the predates the revolution and we were not disappointed. The waiter was so curt that we just had to laugh. Dinner conversation was relaxed and mostly in English. That is something I really like about the French I've met: if there is one English speaker in a crowd they will all speak English, even to each other, out of politesse.

A perfect April morning heralded the day that best typifies my experience in Prague. I sallied forth to the main train station in hopes of retrieving my bike. Taking a bike with you on a German train is very difficult and getting it across an international border is impossible; the bike must be shipped separately. It turned out that I was importing my bike to the Czech Republic, and that I had to go to the customs office. Of course, the ten people in front of me had stacks of documents for importing cars, radioactive medical isotopes, etc. I stood in line for 45 minutes. It is incredible sometimes to see the two cultures here. One is the usual Western tourist culture, which lubricates a smooth journey from the airport to your downtown hotel, then out to dinner and sightseeing. The other is the old imperial bureaucracy of which Kafka wrote so eloquently. This culture flourished under the Communist regime and is alive and well at the train station: no one thought to separate ordinary tourists with a single bag to claim from businessmen importing tens of thousands of dollars of stuff.

In a country as exotic as the Czech Republic, almost any situation can be educational, and this one proved to be rather fortuitous. Behind me was Arnost, a Czech architect who had applied for foreign travel every year for sixteen years under the Communist regime. Finally, in 1984, he was given permission to travel to Denmark to see buildings. He stayed there and has been working as an architect ever since. Unfortunately, recently the market for architects has gone sour. "My boss told me that there wasn't even enough room for Danish architects these days and that I would have to leave." I told him that I'd always thought of Scandinavians as having such well-ordered societies. "They probably did, but as soon as a lot of Eastern Europeans arrived, prejudice developed quickly." How had he adapted to Danish culture? "I wanted to get married, but most Danish women live only for themselves; they aren't ready to take care of a family. There's isn't much of a Czech community; we tend to melt into the surrounding culture. Most of my friends were actually Polish immigrants."

We also chatted with the friendly medical isotope importer who ducked outside for a cigarette. Attitudes toward smoking here are very different from Germany. First of all, Czechs seem to observe "no smoking" signs. Second, it seems to be rude here to smoke in front of non-smokers. Finally, Germans think cigarette smoke is positively healthful, but this fellow said he never smoked inside his house so as not to expose his children.

When Arnost and I got to the front of the line, we were told that our bikes were on the other side of town at the Holesovice station. I kept my good humor, but Arnost was outraged that his home country could be so inefficient. I said that he'd been spoiled by Denmark and perhaps could not live happily here after all, especially on the $300/month that he was expecting to be paid.

When we got to Holesovice, the baggage office had arbitrarily closed for lunch (people get up at 5:00 and start work at 6:30 so this should have come as no surprise). We toured around the upper floors of the station to find someone in authority, but everyone told us we would just have to wait. By the time we got back downstairs, the office was magically open again and we presented our tickets. The man said that we should have gotten a stamp back at the main station and that we'd have to go back. Arnost pleaded with him in Czech and somehow our bikes were set free. Mine was in a box padded out with excess clothing and weighed about 25 kg. Getting it home on the metro and then up five flights of stairs was enough to make me regret having brought the bike from America in the first place.

After assembling the bike, I headed down Sokolska Street, a one-way four-lane city street that the Czechs somehow regard as a superhighway and over the Nuselsky Most, a large modern bridge about 1 km long spanning a dramatic valley filled with old houses. Just to be spinning along the street with a blue sky overhead and a fine wind in my face made me forget all of the travails associated with schlepping the bike.

The Vysehrad castle would have been a rather hot and tedious excursion on foot, but was marvelous on the bike. In America, someone would have thought to put up a "no bikes" sign, but there aren't many bikes here yet and restrictions seem to be few. I rode down the hill to Plzenska where I bought apples and, I am ashamed to admit it, a meal at McDonald's. This was my first stop at McDonald's during this entire European trip. I justified it by saying that it would be a cultural experience to see how McDonald's and Czech culture mix. The result is just like one of the drug-money-laundering McDonald's in Miami: prices are low, the food is greasy, and nobody speaks English.

I then rode up to Mozart's villa and the falling-apart stadium complex. The Communists used to have bizarre synchronized gymnastics in the stadium, the world's largest, with 160,000 performers and 220,000 spectators. The stadium shares a hilltop with a model Eiffel tower and a variety of innocent diversions such as a mirror maze. Heading back toward the castle I was distracted by Hanneke and Elske, two Dutch sisters who invited me to join them in a cafe. Weren't they happy to be in a city where everyone is smiling? "We were just saying to each other how unhappy people here look compared to Amsterdam. Your standards are warped after three weeks in Germany," they laughed.

After parting from Elske and Hanneke, which I was indeed loath to do, I biked downhill to the Karlov Most where I spied the best-looking mountain bike I'd seen in Europe, a superdeluxe aluminum Scott with Rock Shox and XT components. Ivo, the proud owner, makes his living doing commercial art for advertising and lives to mountain bike and paint fine art. I asked him where I could find a bike part and he responded by saying "follow me." Ivo took off down the packed-with-pedestrians bridge at about 15 kph. His if-you-don't-like-the-way-I-drive-get-off-the-sidewalk biking style did not seem to surprise many Czechs. After all, this is the way they drive their cars.

Speaking of cars, I was shocked by the number of brand-new Mercedes on the streets of Prague. It was sickening enough in America to see a doctor drive by in a hunk of sheet metal worth four years salary to the average worker. I wondered how Czechs feel when they see a businessman get so fat from just a few years of the free market that he can afford the same car, worth about 50 times the average annual salary here.

I rode home to shower and then had dinner with Leona, a 19-year-old

Czech from the countryside. We'd met on the Karlov Most

my first night in Prague where she told me that she'd come here to

learn English and work as a secretary. Taking her out to dinner I

felt a bit like George Darrow in Edith Wharton's The Reef.

Darrow is a 35ish American who goes to Paris to meet a woman he loves.

He gets a telegram while on the train telling him not to come, but he

has arranged time off work and hence decides to go anyway. On the

train, he meets Sophy Viner, a beautiful 20-year-old who is going to

visit friends. Sophy's friends have left Paris so Darrow puts her up

in his hotel and starts to show her around the city. Things that seem

uninteresting to his jaded eyes look wondrous to hers and her

enthusiasm proves infectious.

I rode home to shower and then had dinner with Leona, a 19-year-old

Czech from the countryside. We'd met on the Karlov Most

my first night in Prague where she told me that she'd come here to

learn English and work as a secretary. Taking her out to dinner I

felt a bit like George Darrow in Edith Wharton's The Reef.

Darrow is a 35ish American who goes to Paris to meet a woman he loves.

He gets a telegram while on the train telling him not to come, but he

has arranged time off work and hence decides to go anyway. On the

train, he meets Sophy Viner, a beautiful 20-year-old who is going to

visit friends. Sophy's friends have left Paris so Darrow puts her up

in his hotel and starts to show her around the city. Things that seem

uninteresting to his jaded eyes look wondrous to hers and her

enthusiasm proves infectious.

Leona had never had Chinese food, so I took her to the nearby Peking restaurant. There were no Chinese in evidence, either as staff or customers, and some of the food was barely recognizable as Chinese (they served rolls, for example). If I'd been alone, it would have been a disappointment, but I had fun teaching Leona to eat with chopsticks and learning about her world. She gets up at 5:00, is working at 6:30, and is ready to swim or run by 2:30. Leona spends her afternoons playing guitar or singing folksongs with her friends. In the evenings she attends English class. Leona didn't have anything nasty to say about anyone or anything, not even about the Russians who made her learn their hellishly complex language for eight years. Yet when I told her how happy I was to be able to speak some German, she said flatly "I don't like Germans." Evidently the numerous German tourists are not doing much to heal old wounds.

Towards the end of the evening, I didn't feel like Darrow anymore. Due to my age and privileged birth I had a wider experience of the world, but Leona had the absolute authority of a beautiful woman. I felt like a Bonfire of the Vanities Master of the Universe in the Chinese restaurant, like an equal partner in the hip cafe afterwards, and like a bewildered child at the end of the evening.

"You'll pry my bike from my cold, dead hand"--that's how I felt on my

last day in Prague. Not only was I able to ride through 20 miles of

"real Prague" neighborhoods and visit an obscure Renaissance palace, but

I even biked a downtown walking tour from the Cadogan guide that

included the famous Bambino di Praga. The Bambino is a

wax infant Jesus said to perform miracles for those with cash to spare.

The infant is pretty well fixed, being particularly venerated throughout

the Hispanic world, and has scores of fine costumes from all over the

world (even one from Communist North Vietnam).

"You'll pry my bike from my cold, dead hand"--that's how I felt on my

last day in Prague. Not only was I able to ride through 20 miles of

"real Prague" neighborhoods and visit an obscure Renaissance palace, but

I even biked a downtown walking tour from the Cadogan guide that

included the famous Bambino di Praga. The Bambino is a

wax infant Jesus said to perform miracles for those with cash to spare.

The infant is pretty well fixed, being particularly venerated throughout

the Hispanic world, and has scores of fine costumes from all over the

world (even one from Communist North Vietnam).

More tourists would be well-advised to stop and worship the Bambino: just outside the church, a Frenchwoman stopped me to ask, in excellent English, directions to her embassy. She'd had her money and papers stolen. I got off my bike and accompanied her for the two blocks.

On the Karlov Most, I met the Italian girls again, which was like getting an extra dose of sunshine. Ariana had found a picture-with-a-python entrepreneur mid-bridge and was posing with a five-meter-long snake around her neck. Knowing that they were all the same age, I was struck by the contrast between Christina, mature and seductive, and some of the others, slight and childlike. They demanded to know why I wasn't married. I said "I'm waiting to meet the right Italian girl."

While attempting to hold two sausage sandwiches, one Coke, and one mountain bike, I was greeted familiarly by two Danish girls. "Do we know each other?" I asked. They said "Of course, you are the German teacher from our hotel!" I laughed "Ich spreche Deutsche aber nicht zehr gut!" They insisted "you aren't a teacher of German, but a teacher from Germany." Only after I took off my helmet were they convinced that I wasn't from Germany. "That's better that you are American anyway; we really don't like Germans very much." I wondered how Europeans could ever truly unite given so many old and new cross-border wounds.

As the red glow of the sunset melted the Baroque palaces along the Moldau, I met Hanneke and Elske at the Czech Philharmonic. Three dollars bought a ticket in the 15th row of the orchestra, in between two friendly attractive Czechwomen who translated the program notes for me. When the orchestra came out, I exclaimed that it was all white males. A retired Czech gentleman sitting behind us smiled with satisfaction: "that is why they are good." Despite their politically incorrect composition, they played a challenging program as well as my own Boston Symphony Orchestra. The acoustics in the elegant hall are marvelous, mostly because is has only half as many seats as the newer American halls and everyone is close to enough to get good sound.

Afterwards, we three went to the main square to sit in a cafe and chat about the concert, culture and American vs. European life. On the way, I mentioned that Dvorak had so loved the New York subway that he refused to ride in his chauffeured limousine. Elske asked me if it was true that only poor people ride the NY subway now. I said "yes, but in New York anyone making less than $100,000/year is considered poor."

Elske is one of those women who drives men to distraction with sheer indifference. Let a woman give a man her heart and soul unreservedly and he'll soon take her for granted. But if a woman holds herself back, a man will go to extreme lengths to bring a sparkle to her eyes. He'll do this day after day because every time he succeeds he gets a feeling of accomplishment.

Elske is a hard-working medical student and hadn't ever been to the U.S. She disarmingly asked "Why would I want to visit the U.S.?" I was nonplused. I'd met people who hated the U.S. I'd met people who loved the U.S. But I'd never met anyone who was simply indifferent to the country that draws more tourists and immigrants than any other. I'm not sure if this reflects my American or my male bias, but my first thought was of size: "Hey, we've got three lakes that are substantially larger than Holland!"

Images of Disneyworld, the canyons of the Southwest, bears in Alaska, vast art museums, Henry James's Boston, Vermont foliage, New York skyscrapers, San Francisco vistas, the Rocky Mountains, and the Oregon Coast flashed before my eyes. It was just like watching a TV station sign off the air except that everything looked unimpressive and deflated under Elske's cold, unwavering gaze. Rather than try to stretch words to describe the beauty and variety I'd just seen inside my eyelids, I moved to an intellectual plane.

I told Elske and Hanneke that Americans are curious about Europe because that is a source of so many of our cultural ideas. By the same token, Europe now gets many ideas from America and they might be curious to see the source. For example, America was the most thoroughly middle class society for parts of the 19th century and a lot of European modernity is modeled after the States. Big city life and problems came first to America and then to Europe.

We also discussed chauvinism and nationalism. They proudly noted that they weren't chauvinistic about things Dutch. I said "So what? I'm not chauvinistic about Massachusetts. You are chauvinistic about Europe, which you see as the center of things and the only really interesting place, but not about your tiny little corner. Americans, if you leave out a few Texans and Californians, are not chauvinistic about their little states, but do feel there is a richness to the entire U.S."

It occurred to me that Europeans don't have a visceral feel for the multiculturalism of the U.S. They can get a tourist's appreciation of authentic cultures quickly, but don't have the day-to-day contact with watered-down cultures that Americans have. I said that seeing my Chinese friends every day and learning what concerns they and their families have teaches me different things about Chinese culture than a tourist trip to China might.

My sales pitch wasn't effective, for Elske would not consider visiting the U.S. Instead, she was going to Tanzania for the summer to play Albert Schweitzer. I was stunned. It is so easy for an American to forget that, in Europe, doctors are paid ordinary salaries and people study medicine because they have a genuine desire to help others.

Feeling that I hadn't sufficiently beaten them up about how small Holland was, I proceeded to question Elske's utopian feminism, which is not quite as unfashionable in Holland as in the U.S. She said that in fifty years there would be no differences between men and women. I said that was absurd and that women were more frequently "feet on the ground" types, content with simple things if they did the job. It was men who were likely to have crazy, risky ideas. "Would a woman have said `let's take an enormously heavy bridge and just hang it from two steel wires'?" I asked. "A woman might have noted that there were plenty of lower risk bridge designs and that, in any event, one could take a boat across or just stay on one side. Women are right, of course, as illustrated when the Tacoma Narrows suspension bridge collapsed shortly after it was completed. However, society only advances when crazy ideas are refined into better ways of doing things." This kind of sexism would have gotten me knifed back home in Cambridge, but Elske took it all with good humor and we parted in fine spirits.

Between talking past midnight, disassembling my bike, packing, and having to get up at 5:30, I only got a few hours of sleep. Putting the bike on the plane was far easier than in Boston and things went fairly smoothly until I tried to change my crowns back to dollars. One can't do this without the original receipt from the first change. However, as I tried to auction the money off among the departing passengers, the duty free shop manageress took pity on me and opened up. I was the first person in Czech history to buy duty free goods with crowns, as this was the first day that they were accepting Czech currency and the shop did not officially open until 8am. My bag swelled with about 2 kg. of Lindt chocolate.

The two-hour flight to Heathrow blossomed into a six-hour ordeal thanks to fog and running out of gas while circling. Shelly, sitting in the aisle seat, entertained me with his 38-year-old single Jewish New Yorker's perspective: "Eight million people in NY, eight million stories. Eight million people in LA, one story." Shelly quit his job at a big NY law firm because he couldn't stand the people he was meeting, especially the women who'd been reduced to materialism and savagery by having to live the NY yuppie life. "I'm despairing of finding a sane North American Jewish woman, except among the orthodox. The secular ones have been on too many dates with dentists. They become so starved for experience that they run off on wild flings in Italy or into bad marriages."

At Heathrow, I had to dodge crowds of wool-suited executives railing at hapless airline employees for ruining their million-dollar deals. I flew standby on the last flight to JFK and then standby again on the last flight to Boston, arriving at my front door 25 hours after getting into the taxi in Prague.

Epilogue

A couple of weeks after I returned, I showed slides from the trip at

my house. My friend Ted brought a couple visiting from Stuttgart and

they kept their opinions to themselves until he was driving them home:

"We liked the slides, but it would be unthinkable in Germany to speak

about the Nazi period except in the most serious terms." Ted said he

didn't find the tone inappropriate and a discussion ensued.

Frustrated that he wasn't getting his point across, the professor said

"Well, what if there had been a Jew present?" When Ted told him that

he was Jewish, that at least 20 of the 50 guests were Jewish, and that

the host/photographer/narrator was Jewish, the Germans were stunned

into silence.

It seemed almost laughable on one level, particularly since one of my

friends is Orthodox and was wearing a yarmulke. On another level, it

seemed that complete ignorance of Jewish culture would be the natural

consequence of Nazi persecution and the Holocaust. (The Jewish

population of Germany reached its peak in 1920 at 500,000. By 1937,

365,000 Jews remained and only 17,000 were left at the end of the

war.) It struck me then how much Jews and other minorities were The

Other in Europe.

In America, a television portrayal of a homeless man in New York City provokes sympathy from 90% of the viewers. "I might be a racist and that guy is black, but he's an American and he sleeps in the street. We should do something to help him," is a typical response. Starving Somalis or the Coast Guard packaging up a bunch of Haitians into a shipping container excites very little sympathy: "There are a lot of wretched people on this planet and we can't help all of them." What's the difference? The Haitians and Somalis aren't part of our family.

Just because we're a family doesn't mean there isn't hatred. In fact, no matter how racist one is, one probably has hated one's sister more than any abstract person of another race. But even if you hated your sister more than anyone else in the world, would you put her in a Concentration Camp?

Minorities in Europe, however, are not protected by any feeling of family. A few times I asked good-natured open-minded Germans whether they thought the woman on the subway was correct, i.e., was it possible for a 2nd or 3rd-generation Turkish immigrant to become "truly German" in any sense? The idea was so absurd to them that they looked bewildered at first. None of them felt the Turks were inferior, but none felt any kind of bond with them either. Nor is this phenomenon restricted to Germany. I met a young Danish university student who deplored the anti-immigrant prejudice of his fellow Danes. "Of course, many of these immigrants make matters worse by not converting to Christianity. I'm not a believer myself, but that is the religion of our country." Third World countries are no better; Muslim Arab immigrants to Muslim Arab Egypt can expect to wait 125 years to get citizenship.

The most valuable thing I learned visiting Berlin and Prague was an appreciation for what I'd always taken for granted: a person can show up on our shores and expect to become "one of the family" after a few years.

The End

Return to the cover page

Return to the cover page

You might be interested in other travel writing by Philip Greenspun

philg@mit.edu

Add a comment | Add a link

After bomb-scarred Dresden, the storybook valley of the Elbe was

particularly beguiling. Our train traveled up this river for about

three hours. The German side is studded with fine old houses and

occasional towns nestled into side canyons. The walls of the valley

are often quite steep, with sheer rock faces 75m high in some places.

Eastern Germans bicycled along the road on the other bank and the

river was ever so flat and lazy. Once we got to the Czech Republic,

the river became much more industrial and houses lost their charm.

After bomb-scarred Dresden, the storybook valley of the Elbe was

particularly beguiling. Our train traveled up this river for about

three hours. The German side is studded with fine old houses and

occasional towns nestled into side canyons. The walls of the valley

are often quite steep, with sheer rock faces 75m high in some places.

Eastern Germans bicycled along the road on the other bank and the

river was ever so flat and lazy. Once we got to the Czech Republic,

the river became much more industrial and houses lost their charm.