|

A Photographer's Guide to Ecuador, the Galapagos, and Peruby Philip Greenspun in December 2004 |

"So immense is the scale on which Nature works in these regions that it is only when viewed from a great distance that a spectactor can in any degree comprehend the relation of the parts to the stupendous whole"Ecuador and Peru offer the possibility of, within just two or three weeks, simultaneously challenging your wildlife, landscape, architecture, and people photography skills.

-- W.H. Prescott, History of the Conquest of Peru, 1847

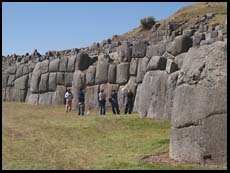

In the Andean highlands you can photograph a civilization built on the slopes of granite mountains where people can look up 3000' from their frontyards to the snow-capped peaks and from their backyards look down 3000'into a canyon. The traditions and some of the stone buildings go back thousands of years. On the eastern side of the Andes you will find the authentic Amazon basin where Indian guides show you diverse but elusive wildlife that will give your 600/4 lens with teleconverter a good workout. In the colonial cities you'll find 400-year-old Spanish architecture and streets. In the Galapagos you'll take animal portraits with a 50mm lens.

Europe, Asia, and North America offer two mutually exclusive alternatives: spectacular landscape or interesting cultural attractions. We have built our towns in flat areas and abandoned the high mountains as wilderness. Here in the U.S., for example, it is too expensive and difficult to build roads and houses in the Sierra or the Rockies so we've left them (mostly) alone. By contrast in equatorial South America people needed to climb to 10-14,000' above sea level in order to grow staple crops. Thus the 1000-year-old city and dramatic mountainside are in one and the same location.

Lima has a reputation for crime so it is best to take taxis at night and hire a tourist guide if you are going to walk around with an expensive-looking camera.

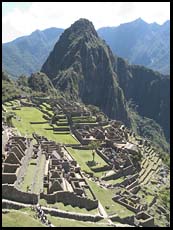

This is what draws everyone to Peru. Machu Picchu was a lost city of

the Incas until 1911 when Yale professor Hiram Bingham began clearing

the jungle around it. Machu Picchu is a bit to low in elevation to have

been ideally suited for growing crops and other standard Inca

activities. It might have been a seasonal retreat for high-ranking

Incas. Despite the fact that Machu Picchu is not all that typical of

Inca lifestyle it is well preserved and in a mysterious location so it

is where all the tourists want to go.

This is what draws everyone to Peru. Machu Picchu was a lost city of

the Incas until 1911 when Yale professor Hiram Bingham began clearing

the jungle around it. Machu Picchu is a bit to low in elevation to have

been ideally suited for growing crops and other standard Inca

activities. It might have been a seasonal retreat for high-ranking

Incas. Despite the fact that Machu Picchu is not all that typical of

Inca lifestyle it is well preserved and in a mysterious location so it

is where all the tourists want to go.

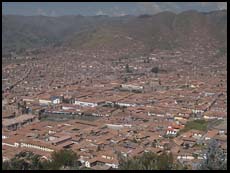

Access is via a short flight to Cusco, a brutal 11,000' above sea level, then a train ride through the Urubamba Valley (9,000' above sea level) for about four hours until you reach the town of Aguas Calientes, only 6500' above sea level. You might be tempted to rest for a few days in Cusco before proceeding to Machu Picchu but if you have started in Lima it is much better to rush as quickly as possible to the lower elevations of Machu Picchu and then come back up towards Cusco as you acclimate.

If you want to make reservations far in advance and pay $500+ per night

you can stay in the Macu Picchu Sanctuary Lodge, at 8000' above sea

level and right next to the ruin. Otherwise you'll stay in the town of

Aguas Calientes and take a bus up to Machu Picchu. Unless you are

acclimated to the high altitude you'll probably sleep better in Aguas

Calientes and the town has a lot more going on than the ruin. There is

a lively public plaza, shops, a choice of restaurants, and hotels

ranging in price from $20 to $180 per night.

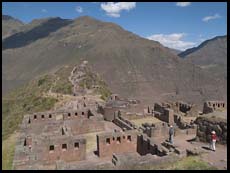

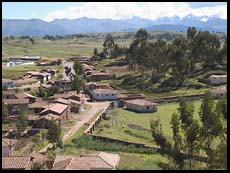

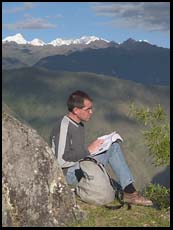

This was in many ways my favorite among the spots that I visited in

Peru. The Urubamba Valley has Inca ruins that are not crowded with

tourists. The Valley is also a good place to see Peruvian highlanders

living in traditional ways: growing crops, weaving, etc. There are

hotels, restaurants, and activities for tourists but most of the

activity in the Valley is by locals for locals. In the dry season, when

the weather is just about perfect, you could easily spend a week in

the Urubamba Valley riding bicycles, taking walks around Inca ruins,

riding horses, and visiting small towns. Don't miss Moray, a series of

concentric circular terraces built into a depression where the Incas

tested crops in the different amounts of sunshine falling on different

areas. Everywhere in the Valley you'll see people farming terraces that

were originally built by the Incas.

This was in many ways my favorite among the spots that I visited in

Peru. The Urubamba Valley has Inca ruins that are not crowded with

tourists. The Valley is also a good place to see Peruvian highlanders

living in traditional ways: growing crops, weaving, etc. There are

hotels, restaurants, and activities for tourists but most of the

activity in the Valley is by locals for locals. In the dry season, when

the weather is just about perfect, you could easily spend a week in

the Urubamba Valley riding bicycles, taking walks around Inca ruins,

riding horses, and visiting small towns. Don't miss Moray, a series of

concentric circular terraces built into a depression where the Incas

tested crops in the different amounts of sunshine falling on different

areas. Everywhere in the Valley you'll see people farming terraces that

were originally built by the Incas.

If you want city services, stay in the town of Urubamba (pop. 8000).

The town of Yucay (pop. 3000) is much quieter and has a nice courtyard

hotel called Posada del Inca. The regular rooms at Posada del Inca are

dark and crummy but the two-room suites are exceptionally nice.

As long as you're in the region you might consider visiting the Amazon

jungle. Most people associate the Amazon with Brazil but in fact

you're much better off visiting the jungle in eastern Ecuador or Peru.

By the time it gets to Brazil the Amazon is an enormously wide river,

the natives have cleared the banks to ranch cattle, and generally the

local flavor is gone. The tributaries that reach up into the Andes

are smaller, the natives are more native, access is more difficult and

therefore the habitat has been less altered.

As long as you're in the region you might consider visiting the Amazon

jungle. Most people associate the Amazon with Brazil but in fact

you're much better off visiting the jungle in eastern Ecuador or Peru.

By the time it gets to Brazil the Amazon is an enormously wide river,

the natives have cleared the banks to ranch cattle, and generally the

local flavor is gone. The tributaries that reach up into the Andes

are smaller, the natives are more native, access is more difficult and

therefore the habitat has been less altered.

This isn't a great region for photography unless you have a lot of time, dedication, and equipment. Ruben, my guide in Tambopata, related the story of a BBC camera crew going up to the top of a platform all day every day for two months to get some of the footage for a 30-minute show.

In the peak tourist season of May through August the Peruvian Amazon is subject to monthly cold fronts coming up from Argentina and Chile. The temperatures can drop to 45 degrees at night and rise to only 60 during the daytime. Bring a wind-proof jacket, head and ear protection, and several layers or you'll freeze to death on the boat rides up and down the rivers.

Rather than slather yourself constantly in insect repellant, you might wish to invest in DEET-impregnated clothing such as the Buzz-Off brand of shirts and pants. Using liquid repellant entails a risk of eroding the markings on plastic cameras and other gear.

If physical comfort is high on your list of vacation priorities choose

your lodge very carefully. Nearly all lodges are off the power grid

and generate power only sparingly in the evenings to recharge

batteries. No power means no air conditioning, no heating, no hot

water, no lighting for reading at night, etc.

If physical comfort is high on your list of vacation priorities choose

your lodge very carefully. Nearly all lodges are off the power grid

and generate power only sparingly in the evenings to recharge

batteries. No power means no air conditioning, no heating, no hot

water, no lighting for reading at night, etc.

There are a lot of different lodges in Ecuador and Peru offering various degrees of comfort and various challenges in getting there. The landscape changes all the time so it is best to talk to the folks at Wildland Adventures who've actually been to some recently and find a lodge that suits your temperament.

I stayed at the Tambopata Research Center, which is remarkable for its concentration of Macaws, up to 200 of which may be seen in the early morning hours at a clay lick. One disappointment was that the lodge did not have any comfortable chairs for reading so it wasn't a great place to relax and make friends because tourists, when not out walking, would retreat to their rooms (cold and damp in May). Most people show up in large groups of family and friends and they all seemed to be having a good time.

The second-smallest country in South America, about the size of

Colorado, Ecuador offers tremendous diversity of terrain, culture, and

wildlife. The land is flat on the Pacific coast in the west, flat on

the Amazon plain in the east, with the 20,000'-high ridge of the Andes

in the middle. The people have grown from 700,000 at independence in

1830 to more than 13 million in 2004, making Ecuador the most densely

populated country in South America. Thanks to the fact that much of

the country is inhospitably high or inhospitably low and humid the

animals haven't disappeared. In fact, one sixth of the world's

bird species make homes here.

The second-smallest country in South America, about the size of

Colorado, Ecuador offers tremendous diversity of terrain, culture, and

wildlife. The land is flat on the Pacific coast in the west, flat on

the Amazon plain in the east, with the 20,000'-high ridge of the Andes

in the middle. The people have grown from 700,000 at independence in

1830 to more than 13 million in 2004, making Ecuador the most densely

populated country in South America. Thanks to the fact that much of

the country is inhospitably high or inhospitably low and humid the

animals haven't disappeared. In fact, one sixth of the world's

bird species make homes here.

Quito has a reputation for pickpockets and muggings. Take taxis at night. Hire a guide if you are going to walk around with expensive camera gear.

To see antiques and crafts, stop into Ag Joyeria, Juan Leon Mera N22-24 at Carrion, and the adjacent boutique.

Good hotel options: Hotel Sierra Madre, Cafe Cultura. If you want something cheap and near the airport, stay at Australian Chris Halliday's hostel, www.theandresrange.com, 593 2 3303 752. There is a new hotel in the old city, Patio Andaluz, but most of the services that you'll need as a tourist are in the new city.

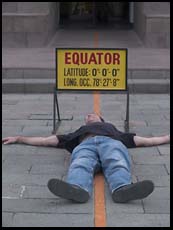

The equator's presence in Ecuador is celebrated in a suburban park called "Mitad del Mundo"

While preparing for your trip you may read disturbing news reports

from Ecuador or Peru. There may be protests, demonstrations, or

strikes. Don't be put off by these stories. Crowds in Latin America

don't tend to turn violent the way a comparable crowd in Africa or an

Arab country might. You're not going to get murdered and have your

relatives back home watching your mutilated body being dragged through

the streets. This is not Iraq. At worst your taxi or bus will be

delayed by a road block for a few hours.

While preparing for your trip you may read disturbing news reports

from Ecuador or Peru. There may be protests, demonstrations, or

strikes. Don't be put off by these stories. Crowds in Latin America

don't tend to turn violent the way a comparable crowd in Africa or an

Arab country might. You're not going to get murdered and have your

relatives back home watching your mutilated body being dragged through

the streets. This is not Iraq. At worst your taxi or bus will be

delayed by a road block for a few hours.

Islamic terrorism is not a risk in Ecuador or Peru.

Street crime is a problem in the big cities, especially Quito and Lima. Leave the Rolex at home and if you're not with a guide leave valuables in the hotel safe. Take radio taxis at night.

Malaria risk tends to be local in the jungle. Some areas are known to be free of malaria and others are potentially risky. The Center for Disease Control doesn't distinguish among areas of the Amazon basin, however, and issues a blanket recommendation to take anti-malaria pills. Doxycycline is one remedy and it makes your skin more sensitive to sunburn. The other pills, e.g., Malarone and Larium, tend to give you nausea and generally make you feel awful, which is a problem if you're proceeding to the high areas where you won't be sure whether your nausea is altitude sickness requiring immediate treatment or merely the side effect of your antimalaria drugs. The Tambopata jungle area that I visited in 2004 was free of malaria and none of the guides or resident researchers were taking pills.

You really must avoid all insect bites due to the risk in South America of contracting leishmaniasis, which is carried by sand flies. Two months after you return home you'll find that this parasite has generated some little ulcers poking up from your skin. Your doctor will be completely clueless of course. Eventually you'll learn that the treatment is 60 injections, two per day for 30 days, of the heavy metal antimony. In the U.S. this will cost about $7,000 so if you don't have health insurance you might find yourself returning to Peru for treatment, which is free to Peruvians and dirt cheap for everyone else. Wear long pants and long sleeves in the evenings and spray yourself with DEET for good measure.

To avoid food poisoning in any Third World country just say "no" to lettuce, even in better restaurants. The Spanish for "without lettuce" is sin lechuga. It is very difficult to purify lettuce even with conscientious washing and disinfecting. Use bottled water for brushing your teeth.

Your skin will take a beating from the high altitude sunshine and dryness. Bring lots of high-test sunscreen, a broad-brimmed hat, and moisturizing lotion.

In jetting from sea level to 9,000' (Quito) or 11,000' (Cusco) the

best that you can hope for is several days of weakness. Most people

will also get a headache, have trouble sleeping, develop a nosebleed,

and have difficulty digesting food. A minority will develop

life-threatening altitude sickness, which can only be treated by

descending at least 1500'.

In jetting from sea level to 9,000' (Quito) or 11,000' (Cusco) the

best that you can hope for is several days of weakness. Most people

will also get a headache, have trouble sleeping, develop a nosebleed,

and have difficulty digesting food. A minority will develop

life-threatening altitude sickness, which can only be treated by

descending at least 1500'.

The best way to avoid altitude sickness is by starting no higher than 7000' and spending a couple of nights at that first stop. Then try to sleep no more than 1000' higher than the night before. In order to avoid repeated acclimitizations construct your itinerary so that you don't go up and down too much. If you're going to see Machu Picchu, the Urubamba Valley, and Cusco, for example, fly to Cusco and immediately embark on the 4-hour journey to Aguas Calientes, which is the town just below the Machu Picchu ruin and is only at 6500' above sea level. Spend two or three nights in Aguas Calientes while doing day-hikes in the surrounding mountains. Then proceed by train to Ollantaytambo in the Urubamba Valley at 9000'. Spend two or three nights in one of the excellent hotels in this region while riding horses, doing tours, and taking hikes in the mountains above. Finish out your tour of the area with a night or two in Cusco. From Cusco you can proceed to the even higher elevations of Lake Titicaca and the various towns in Bolivia.

Whenever you move to a higher elevation drink a lot of water and Gatorade and eat very lightly.

[If a $400+ nightly tab doesn't bother you there is a hotel in Cusco that can pump additional oxygen into their rooms, yielding an effective altitude of perhaps 7000'. This is the Hotel Monasterio and is excellent in all other respects.]

A GSM mobile phone from the U.S. will work in Peru but not, as of

2004, in Ecuador. Ecuador has a GSM network but no roaming agreements

with U.S. carriers such as T-Mobile.

A GSM mobile phone from the U.S. will work in Peru but not, as of

2004, in Ecuador. Ecuador has a GSM network but no roaming agreements

with U.S. carriers such as T-Mobile.

Internet cafes are popular with locals in both Ecuador and Peru at a cost of $1-2 per hour. Many Internet cafes also offer booths in which you can make international phone calls for about 25 cents per minute.

Many Internet cafes and camera shops will take a digital camera's

memory card and burn the contents to CD-ROM.

When researching this article I took 7 flights within Ecuador and

Peru. Aerogal from Quito to the Galapagos and back to Guayaquil

operates old Boeing 727s but they seemed well-maintained and were on

time. One flight actually left 45 minutes early due to a planned

runway closure in Guayaquil. The Aero Continente flight from

Guayaquil to Lima was cancelled. The substitute AeroPostal flight was

4 hours late, resulting in an arrival at the hotel in Lima at 5:30 am.

The Aero Continente flight from Cusco to Lima left 90 minutes

early... just about the time that I arrived at the airport. The tour

company claimed that they had confirmed with the airline and the

airline claimed that they had notified the tour company of the early

departure. All their later flights to Lima were full. It was a grim

scene.

When researching this article I took 7 flights within Ecuador and

Peru. Aerogal from Quito to the Galapagos and back to Guayaquil

operates old Boeing 727s but they seemed well-maintained and were on

time. One flight actually left 45 minutes early due to a planned

runway closure in Guayaquil. The Aero Continente flight from

Guayaquil to Lima was cancelled. The substitute AeroPostal flight was

4 hours late, resulting in an arrival at the hotel in Lima at 5:30 am.

The Aero Continente flight from Cusco to Lima left 90 minutes

early... just about the time that I arrived at the airport. The tour

company claimed that they had confirmed with the airline and the

airline claimed that they had notified the tour company of the early

departure. All their later flights to Lima were full. It was a grim

scene.

In choosing an airline keep in mind that the Andes Altiplano has some of the world's most challenging airports. Cusco, for example, is at 11,000' and a typical mid-day temperature is 20C, much hotter than a standard atmosphere at that altitude. This results in a density altitude of 14,000'. Aircraft don't perform their best in thin air even with the miracle of the jet engine and its compressor. Airfares are pretty low within Peru and travel by road can take days, resulting in flights that are invariably full. A conversation with one pilot revealed that his Boeing 757 out of Cusco was at maximum gross takeoff weight despite having only 2.5 hours of fuel on board. The plane climbed reasonably well but if one of its decades-old engines had failed after takeoff it might not have been easy to steer the plane around the peaks and continue climbing.

The only airline in Peru that has modern planes and high standards seems to be LAN Peru, a subsidiary of LAN Chile. Their Airbus 320 planes are a bit cramped but most flights are only an hour or two. LAN Peru flies more or less everywhere so it might be wise to ensure that any trip you book is exclusively with LAN.

For getting to Ecuador and Peru from the U.S. the airline with the most flights is American Airlines from Miami (I stopped on South Beach and took a few snapshots) and to some extent Dallas. Continental also flies to most Latin American destinations from Houston. Overnight flights are popular with business people who don't want to lose a day of work and for making connections within the U.S. most airlines strive to get passengers into Florida or Texas by 9:00 or 10:00 am. This means that you might be leaving Lima at midnight or 1:30 am.

As of 2004 Lima was subject to long lines for immigration in both directions. It is not uncommon to be standing on line for 1.5 hours. If you're in Cusco, for example, you can avoid this situation by making your way south to La Paz, Bolivia and flying back to the U.S. from there. (It would not be a good idea to fly into La Paz from the U.S. due to its 12,000' altitude.)

Peru is so huge and so varied that it makes a tough guidebook subject.

Lonely

Planet Peru

may be the most useful book overall though

Moon

Handbooks Peru has potential to be more literate. For

background and motivation read Prescott's classic

History of the Conquest of Peru.

Ecuador isn't so overwhelming for tourists or guidebook authors.

Lonely

Planet Ecuador and Galapagos is fairly successful.

For some insight into seasickness and a politically incorrect approach

to native cultures and wildlife, read Darwin's

Voyage

of the Beagle.

Peru is so huge and so varied that it makes a tough guidebook subject.

Lonely

Planet Peru

may be the most useful book overall though

Moon

Handbooks Peru has potential to be more literate. For

background and motivation read Prescott's classic

History of the Conquest of Peru.

Ecuador isn't so overwhelming for tourists or guidebook authors.

Lonely

Planet Ecuador and Galapagos is fairly successful.

For some insight into seasickness and a politically incorrect approach

to native cultures and wildlife, read Darwin's

Voyage

of the Beagle.

You'll want binoculars for the Galapagos and the jungle. Binoculars

are specified as NxM, e.g., "8x42". The first number,

N, refers to the magnification. The second number, M,

refers to the size of the front lens element and a larger number

generally indicates more light-gathering capability. An 8x42 pair,

for example, offers 8x magnification, which is comparable to a 400mm

telephoto lens on a 35mm camera, and a 42mm lens diameter.

You'll want binoculars for the Galapagos and the jungle. Binoculars

are specified as NxM, e.g., "8x42". The first number,

N, refers to the magnification. The second number, M,

refers to the size of the front lens element and a larger number

generally indicates more light-gathering capability. An 8x42 pair,

for example, offers 8x magnification, which is comparable to a 400mm

telephoto lens on a 35mm camera, and a 42mm lens diameter.

Most people aren't steady enough to handhold more than 8x magnification and in the Galapagos you sure don't need more than that because oftentimes you're practically stepping on the animals. If you're using binoculars in twilight or for astronomical observations you might want a 50mm front element or even larger if you can manage the weight. Most people, however, find that 40 or 42mm is adequately bright.

Magnification and lens size aren't the only relevant factors in choosing binoculars. If you wear eyeglasses you will want "long eye relief" so that the full image is viewable even when your eyes are kept back from the eyecups by an intervening eyeglass. For wildlife viewing you want "wide angle" or "wide field of view" so that you have a better chance of spotting birds and other moving creatures. In the jungle you'll need a waterproof and fogproof design.

Minolta makes a remarkably good binocular series for about $150 called the "Activa". These are waterproof, fogproof, wide angle, long eye review, and available in 8x40. They are reasonably light but not especially compact. If your interpupillary distance is narrow you'll appreciate the fact that the two halves come together very close. One of the $1000 German binoculars will yield a slightly better view but if you're already laden with expensive camera gear it is nice to have some binoculars that are cheap enough so you don't have to worry about them.

In the jungle many of the birds will be hard to study without much

higher magnification, e.g., 15-20X. Usually your guide will carry a

tripod and (cheap Bushnell) spotting scope so that you don't have to

worry about preparing for this requirement. If you're interesting in

looking at small birds in detail, though, you might consider the

electronically image-stabilized binoculars made by Canon and Fuji

(Nikon remarkets Fuji's IS binoculars in some markets). These tend to

be heavy.

Suggested Itineraries

Ecuador and Peru together are huge, comparable in area to Alaska. It is

a mistake to try to pack too much into a 10-day trip especially given

that much of the time you might be physically uncomfortable due to

seasickness on a boat, lack of temperature control in the jungle,

altitude sickness in the Andes, etc. Add a few extra days to rest

compared to what you might do within the U.S.