Corcovado

by

Philip Greenspun

Home : Travel : Costa Rica : One Part

Saturday, January 20, 1995

We flew out of Tortuguero in the morning in a Cessna 180 that looked

decidedly old and downmarket after the Piper Twin. The flight was beautiful

and this time I "checked" the yellow river that Edgar had mentioned. We also

saw the highway that we'd taken on the way back from rafting the Pacuare.

Costa Rica is one rugged country and the only way to fully appreciate it is

from the air. We changed planes in San Jose and picked up another

single-engine Cessna for the flight to Carate. We climbed away from the local

airport, over shantytowns and estates, then coffee plantations, and then

stripped hillsides with cabins. The Central Valley has many charms, but not

much wilderness remains.

We flew out of Tortuguero in the morning in a Cessna 180 that looked

decidedly old and downmarket after the Piper Twin. The flight was beautiful

and this time I "checked" the yellow river that Edgar had mentioned. We also

saw the highway that we'd taken on the way back from rafting the Pacuare.

Costa Rica is one rugged country and the only way to fully appreciate it is

from the air. We changed planes in San Jose and picked up another

single-engine Cessna for the flight to Carate. We climbed away from the local

airport, over shantytowns and estates, then coffee plantations, and then

stripped hillsides with cabins. The Central Valley has many charms, but not

much wilderness remains.

Once we were at 6500 feet cruising over the mountains, one could see some

primary forest broken up by ugly gashes. Each gash was a naked clearing with a

cabin, a dirt road that looked impassable, and a few felled trees left lying.

Once we were at 6500 feet cruising over the mountains, one could see some

primary forest broken up by ugly gashes. Each gash was a naked clearing with a

cabin, a dirt road that looked impassable, and a few felled trees left lying.

"It is an unfortunate part of the Costa Rican character that you aren't a man

unless you've cleared some rainforest," Bobby Coto had told us. This was quite

evident from the air.

We followed the Pacific coast and the pilot pointed out Manuel Antonio National

Park, large oil palm plantations and then the Osa Peninsula, which was our

destination. When we touched down on the gravel airstrip at Carate, it

occurred to me that in 90 minutes of flying in a tiny Cessna, we'd gone from

the extreme northeast to the extreme southwest of the country. Costa Rica is

only about four times the size of Massachusetts and one fifth the size of

Colorado.

We followed the Pacific coast and the pilot pointed out Manuel Antonio National

Park, large oil palm plantations and then the Osa Peninsula, which was our

destination. When we touched down on the gravel airstrip at Carate, it

occurred to me that in 90 minutes of flying in a tiny Cessna, we'd gone from

the extreme northeast to the extreme southwest of the country. Costa Rica is

only about four times the size of Massachusetts and one fifth the size of

Colorado.

Check the map of Corcovado (95K)

Downtown Carate proved to be a pulperia next to the airstrip. The

nearest telephone is in Puerto Jiménez, a 90 minute drive around the

coast over a dirt road.

Downtown Carate proved to be a pulperia next to the airstrip. The

nearest telephone is in Puerto Jiménez, a 90 minute drive around the

coast over a dirt road.

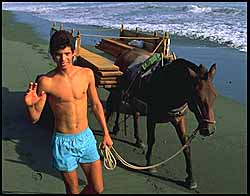

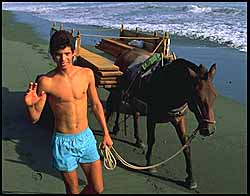

Urbano, a 45-year-old with a face that had been weathered in the hot dry sun of

Guanacaste, loaded our bags into a pony cart. Lana, a blonde from Colorado and

manager of the Corcovado Tent Camp, accompanied us down the beach past

shanties.

"There used to be real houses back in there," Lana explained. "Before this was

a park a lot of people were mining gold here."

A park ranger drove by in a jeep, right past a woman carrying a shovel.

"You aren't supposed to drive on the beach," Lana said. "And you aren't

supposed to dig for gold anymore, but it happens. Anyway, the land back here

is owned by a rich Canadian. He didn't want these people living on his land.

On the other hand, there is a doctrine in Costa Rica that the first 25 meters

back from the beach are public property, so it wasn't really his land. Of

course, you aren't supposed to build a house on public land either, but these

people had been living there for more than seven years and there is another law

that says if you've been living somewhere for seven years then the land becomes

yours. There was a huge lawsuit."

"You aren't supposed to drive on the beach," Lana said. "And you aren't

supposed to dig for gold anymore, but it happens. Anyway, the land back here

is owned by a rich Canadian. He didn't want these people living on his land.

On the other hand, there is a doctrine in Costa Rica that the first 25 meters

back from the beach are public property, so it wasn't really his land. Of

course, you aren't supposed to build a house on public land either, but these

people had been living there for more than seven years and there is another law

that says if you've been living somewhere for seven years then the land becomes

yours. There was a huge lawsuit."

How did it all work out?

"I was coming up the beach one day and I saw hundreds of government troops with

rifles burning the houses," Lana answered. "Obviously the Canadian owner had

talked to the right people. It was a circus. I was taking pictures and one of

the guys with a gun came up to me and demanded my film. I argued with him for

awhile, but eventually handed it over. A guy who works in the lodge came

running through the woods and was taking pictures from the other side. He

stepped out of his sandals and was looking through the camera. He stepped back

into his sandals without looking and right onto a fer-de-lance [the most

aggressive and poisonous snake in Costa Rica]. I eventually got my film back a

few months later."

The beach near Corcovado is lined with almond trees and these are much favored

by scarlet macaws, some of the most beautiful parrots in the world. We saw at

least 40 birds during the 45-minute walk to the tent camp. They were

invariably in pairs, flying side by side or feeding in impossibly twisted

orientations in the almond trees. I asked Lana about them.

The beach near Corcovado is lined with almond trees and these are much favored

by scarlet macaws, some of the most beautiful parrots in the world. We saw at

least 40 birds during the 45-minute walk to the tent camp. They were

invariably in pairs, flying side by side or feeding in impossibly twisted

orientations in the almond trees. I asked Lana about them.

"They live about 30 or 40 years and the adults have no predators," Lana

explained.

There are demonstrations for every conceivable cause practically every day in

Cambridge, Massachusetts. Rainforest preservation just seemed like yet another

entry in a long list of liberal grievances to me. Besides, it was tough to

imagine what I as an American could do about rainforests that were thousands of

miles away. Something kind of clicked (snapped?) in my brain, though, as I

watched the scarlet macaws.

There are demonstrations for every conceivable cause practically every day in

Cambridge, Massachusetts. Rainforest preservation just seemed like yet another

entry in a long list of liberal grievances to me. Besides, it was tough to

imagine what I as an American could do about rainforests that were thousands of

miles away. Something kind of clicked (snapped?) in my brain, though, as I

watched the scarlet macaws.

Parrots are as intelligent as dogs, but we don't share body language with them

as we do with dogs. ["They understand our language," Diane Ewing was later to

say to me, "but we don't understand theirs."] They form complex communities

and marriages between individuals that last decades. The abundance of parrots

in the New World was one of its most salient features to early European

explorers. In fact, a proposed name for the continents was "Land of

Parrots."

By the time we'd reached the tents, cutting down the parrots' habitat seemed to

me just as evil as going over to a neighborhood in Boston and burning all the

houses down. What right had we to destroy these communities of magnificent

lords of the forest?

By the time we'd reached the tents, cutting down the parrots' habitat seemed to

me just as evil as going over to a neighborhood in Boston and burning all the

houses down. What right had we to destroy these communities of magnificent

lords of the forest?

After we settled into our charming little tent, replete with flowers and clean

towels, we went for a swim in the warm Pacific. The surf was pounding, though,

and visibility poor. After the swim, we lunched with Jeffrey De Vito, a

Californian with a religious zeal for taking tourists up into the rainforest

canopy.

The rainforest canopy was pretty much ignored for the first few hundred years

of exploration. Somebody eventually got the brilliant idea that the most

action would logically be where there was the most light, i.e., up in the

canopy. One biologist intensively sprayed area of the canopy with insecticide

then counted all of the dead stuff that fell to the ground. Donald Perry was

among the first biologists to take a direct approach: actually go up into the

canopy and observe.

The rainforest canopy was pretty much ignored for the first few hundred years

of exploration. Somebody eventually got the brilliant idea that the most

action would logically be where there was the most light, i.e., up in the

canopy. One biologist intensively sprayed area of the canopy with insecticide

then counted all of the dead stuff that fell to the ground. Donald Perry was

among the first biologists to take a direct approach: actually go up into the

canopy and observe.

Jeffrey has built a platform in the canopy of some virgin rainforest

just behind the tent camp and adjacent to Corcovado National Park.

"All of our financing is private," Jeffrey noted. "Costa Rica is at a crucial

point right now. In the next few years it is going to be either developed into

another Hawaii or Cancun or developed with some sensitivity in a sustainable

manner. We have to show people that preserving the rainforest is profitable

and leads to sustainable development."

After lunch, we hopped onto a couple of scrawny poky horses with Urbano as our

guide. Chantal hadn't been on a horse for eight years, but she took to her

mount, whom she dubbed "Matthew" because that was as close as she could get to

the Spanish name, with gusto.

After lunch, we hopped onto a couple of scrawny poky horses with Urbano as our

guide. Chantal hadn't been on a horse for eight years, but she took to her

mount, whom she dubbed "Matthew" because that was as close as she could get to

the Spanish name, with gusto.

This was right up there with the Tortuguero boats in my book of Great Ways to

see the Rainforest. With the horse handling locomotion and watching the beach

for obstacles, I could look straight up into the almond trees at the scarlet

macaws. I was hot and sweaty but not soaked in perspiration or unable to see

through fogged glasses.

We walked up the beach, into "Downtown Carate" and then up the road toward

Puerto Jiménez. We passed some tiny farms and then climbed up over a

lake. We had to turn around at the gate of an estate. Urbano explained that

it used to be possible to go all the way around the lake and back to the beach,

but a rich gringo had bought the estate, locked the gate, and ruined

everything.

We walked up the beach, into "Downtown Carate" and then up the road toward

Puerto Jiménez. We passed some tiny farms and then climbed up over a

lake. We had to turn around at the gate of an estate. Urbano explained that

it used to be possible to go all the way around the lake and back to the beach,

but a rich gringo had bought the estate, locked the gate, and ruined

everything.

On the way back, Urbano spotted some spider monkeys up in the canopy. We

pushed the horses into the forest a bit and looked up while one of the monkeys

looked down at us. The most bizarre incident was when one monkey got chased

out of the canopy by his fellows and stood in the road looking back into the

forest. We watched him for awhile then started back while a couple of Costa

Rican kids ran out to look at the monkey. One of them picked up some gravel,

presumably to throw at him.

On the way back, Urbano spotted some spider monkeys up in the canopy. We

pushed the horses into the forest a bit and looked up while one of the monkeys

looked down at us. The most bizarre incident was when one monkey got chased

out of the canopy by his fellows and stood in the road looking back into the

forest. We watched him for awhile then started back while a couple of Costa

Rican kids ran out to look at the monkey. One of them picked up some gravel,

presumably to throw at him.

We rode back along the beach as a beautiful sunset developed over the Pacific.

A communal fish dinner awaited at the tent camp, which we shared with Jeffrey's

Treetops Explorations staff and two Dutch women, Ati and Manon. I asked

Jeffrey what was the toughest part about living in the jungle for months.

"I'm kind of a phone and email junkie so when I go back to San Jose, which is

about once every month, I run up a huge phone bill. Then there are the little

inconveniences of living in the tropics, such as the Bot Fly."

Bot Fly?

Bot Fly?

"The Bot Fly somehow gets its eggs onto the stingers of insects like

mosquitoes. When you get bitten by the mosquito, the Bot Fly eggs are inserted

under your skin and they hatch into little white worms, about an inch long and

fat. The worms start moving around, eating your flesh, and tunneling up to the

surface for air. It is the most incredibly painful thing you've ever

experienced."

Had he ever gotten bitten?

"My girlfriend and I went camping out of Sirena [in the middle of Corcovado

National Park] and it was very hot so we slept without much covers. I later

discovered that I had three Bot Fly worms living in my ass."

What did he do?

"The native remedy is to put a strip of bacon over the worms, which you can see

right through your skin. The Bot Fly needs air so it tunnels up through the

bacon and you just peel the bacon off when this happens and goodbye Bot Flies.

Unfortunately, in my case only two of the three worms came through and the

third one died under my skin. I got a nasty infected boil and I had to go to a

doctor in San Jose to have it removed."

How much did it cost?

"I didn't have to pay for it, but it probably would have been about $50. It

only took about half an hour. My girlfriend was back in Boston by the time she

discovered her bites. We talked about it on the telephone and I told her what

to do. Unfortunately, she used a big sausage instead of bacon and she fell

asleep, which I told her not to do. The Bot Flies came out but then they went

back in after they'd had their air. She ended up going to Beth Israel hospital

where they had no idea what to do. They called every tropical disease

specialist in the country and when they were through, summoned every intern and

doctor in the hospital to watch the extraction. They even videotaped her rear

end while they removed the Bot Flies. It took eight and a half hours and cost

thousands of dollars."

Sunday, January 21, 1995

Corcovado serves a 5:30 breakfast for people crazy enough to take the

morning Treetop Explorations tour. At 6 a.m. we met with Jeffrey, Oswaldo, a

bearded Costa Rican, and Taylor, a young New York/San Francisco outdoors type.

We had to sign a liability waiver before leaving. This freed Treetop

Explorations from responsibility even if they were negligent and tried to make

sure that any litigation happened in Costa Rica rather than the U.S."

Corcovado serves a 5:30 breakfast for people crazy enough to take the

morning Treetop Explorations tour. At 6 a.m. we met with Jeffrey, Oswaldo, a

bearded Costa Rican, and Taylor, a young New York/San Francisco outdoors type.

We had to sign a liability waiver before leaving. This freed Treetop

Explorations from responsibility even if they were negligent and tried to make

sure that any litigation happened in Costa Rica rather than the U.S."

"We have some assets in the United States that we'd like to protect," Jeffrey

explained, "though we are insured to the hilt."

We started walking up to the platform.

"The hardest part of the tour is the hike up," Jeffrey had said. He wasn't

kidding. Even at 6:45 a.m., Corcovado is hot and humid enough to make walking

up the mountainside tough. I was wearing my photo vest stuffed with lenses and

sweat soaked all of my clothing within minutes.

"We're walking through secondary forest right now," Jeffrey said, "and it turns

out that secondary forest may actually support some species of birds better

than primary forest. A lot more research needs to be done before we disdain

secondary forest."

How much of Costa Rica was primary forest?

How much of Costa Rica was primary forest?

"It was 85% in 1964. Now it is down to 26% and about 22% of the country is

under some form of protection, national parks comprising 8%," Jeffrey

replied.

What has happened to the population in that time?

"It was about two million in 1964 and a little over three million now," Oswaldo

answered. "We have one of the highest population growth rates in the world

because everyone is Catholic, but it is changing."

"The main problem is money," Jeffrey said. "The 22% under protection isn't

even safe because not all of the land has been paid for. Costa Rica has about

the highest per capita debt of any country in the world. The banks that made

all of those loans were crazy to think that a country like this could ever pay

them back. The World Bank is the #1 enemy of the Costa Rican rainforest."

"The main problem is money," Jeffrey said. "The 22% under protection isn't

even safe because not all of the land has been paid for. Costa Rica has about

the highest per capita debt of any country in the world. The banks that made

all of those loans were crazy to think that a country like this could ever pay

them back. The World Bank is the #1 enemy of the Costa Rican rainforest."

[I later learned that the debt is about $4 billion, or about $1,200/person.]

Fortunately for me, the Treetops crew stopped every few minutes on the way up

to point out various features of the ecosystem. We admired beautiful Scarlet

Tanagers, small black birds with bright red markings, and studied termite

trails on the underside of tree branches. Butterflies were visible at every

point on the trail, including the beautiful electric blue Morpho. Costa Rica

is home to more than 1500 species of butterflies, more than all of North

America, and most of them seem to be at home in Corcovado.

When we got up to the platform, Jeffrey, Taylor, and Oswaldo began putting

ropes and harnesses together.

"We thought about building a platform between a couple of trees," Jeffrey said,

"and had all kinds of designs with slip joints but then we talked to a lot of

arborists and ended up just with this one 500-year-old Aho tree. We assembled

it in Berkeley just to make sure that we had all of the pieces. The hardest

thing was getting 3000 lbs. of equipment down here. United Airlines gave us a

break on the air freight, but the day it was scheduled to leave Miami was the

second day of a huge hurricane. The captain just didn't want to take off and I

had to explain to him the importance of the project and how I had people on the

ground in Costa Rica waiting to move it through customs. In the end, we got it

down here on schedule, but it came marked as air freight instead of baggage and

that ruined all of our arrangements. We had to pay an extra $1000 to get it

out."

"We thought about building a platform between a couple of trees," Jeffrey said,

"and had all kinds of designs with slip joints but then we talked to a lot of

arborists and ended up just with this one 500-year-old Aho tree. We assembled

it in Berkeley just to make sure that we had all of the pieces. The hardest

thing was getting 3000 lbs. of equipment down here. United Airlines gave us a

break on the air freight, but the day it was scheduled to leave Miami was the

second day of a huge hurricane. The captain just didn't want to take off and I

had to explain to him the importance of the project and how I had people on the

ground in Costa Rica waiting to move it through customs. In the end, we got it

down here on schedule, but it came marked as air freight instead of baggage and

that ruined all of our arrangements. We had to pay an extra $1000 to get it

out."

In bribes or fees?

"In fees," Jeffrey said. "We'd rather pay a little more money than get into

bribes and encourage that kind of thing."

I'd expected the platform to be a wooden tower built in a clearing in the

forest, but that obviously isn't in the best spirit of conservation. Instead,

we looked up to find a grid of yellow fiberglass-epoxy surrounded by leafy

branches. A couple of ropes hung down.

I'd expected the platform to be a wooden tower built in a clearing in the

forest, but that obviously isn't in the best spirit of conservation. Instead,

we looked up to find a grid of yellow fiberglass-epoxy surrounded by leafy

branches. A couple of ropes hung down.

"We're just putting this harness on you as a belay," Oswaldo explained, "it

won't be used at all if the sling works properly."

How many people have ended up hanging from their body harness?

"None," Jeffrey laughed.

[They'd been operating since December 10, i.e., for a little over a month.]

Some combination of whistles, radio, and winching was used to hoist me up about

130 feet in a minute or two. I concentrated on looking at the trees and

branches at eye level.

When I arrived at the platform, Jeffrey hitched my harness onto a "monkey's

tail" bolted to the tree, then unhitched me from the belay.

I'd expected to see a lot more wildlife up here in the canopy than I'd seen

from the ground; I didn't. We did see quite a few spider monkeys at our level

and fairly close, also circling white hawks, feeding hummingbirds, tree

squirrels, vultures, and lots of "little birds" that the naturalists had no

trouble identifying. Being up in the canopy was its own reward, however, and

even if we'd seen no wildlife it would have been worth it.

I'd expected to see a lot more wildlife up here in the canopy than I'd seen

from the ground; I didn't. We did see quite a few spider monkeys at our level

and fairly close, also circling white hawks, feeding hummingbirds, tree

squirrels, vultures, and lots of "little birds" that the naturalists had no

trouble identifying. Being up in the canopy was its own reward, however, and

even if we'd seen no wildlife it would have been worth it.

Chantal stands next to a "walking tree," which actually can move several meters/year. Two second exposure.

Chantal stands next to a "walking tree," which actually can move several meters/year. Two second exposure.

Corcovado Tent Camp has no hot water and I was damn glad for that when we got

back around 11:30. After standing under a cold shower for 15 minutes, I felt

sufficiently civilized to go in for lunch, take a few photographs, then hang

out in the hammocks by our tent.

Nature seemed to be saying "stay in the camp.... stay in the camp...." for she

sent us five spider monkeys and several pairs of the magnificent scarlet

macaws. We could see them from right in front of our tent so there was no

reason on earth to leave the hotel. Chantal wanted to go on the Rio Madrigal

hike, which other guests had raved about.

"If you're already tired, I wouldn't go," Lana cautioned a middle-aged

Iranian-American. "It's kind of a difficult trail."

I didn't feel all that tired, but I should have taken her advice because a

"difficult trail" in Costa Rica generally means no trail at all.

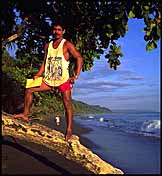

Felipe wore a perpetual smile, no shoes, and the kind of ropy muscles that one

gets from 28 years of living in this area. He took us up the mountain first

via a dry creek bed, then straight up a dry slippery hillside. We walked about

150 feet across a slope that featured a sharp drop-off to the left, steadying

ourselves on tree trunks. It didn't seem as though we were gaining all that

much altitude, but my heart pounded and sweat poured off my face in rivers. I

was sufficiently out of it that I never noticed where I dropped my prescription

sunglasses.

Felipe wore a perpetual smile, no shoes, and the kind of ropy muscles that one

gets from 28 years of living in this area. He took us up the mountain first

via a dry creek bed, then straight up a dry slippery hillside. We walked about

150 feet across a slope that featured a sharp drop-off to the left, steadying

ourselves on tree trunks. It didn't seem as though we were gaining all that

much altitude, but my heart pounded and sweat poured off my face in rivers. I

was sufficiently out of it that I never noticed where I dropped my prescription

sunglasses.

[My sunglasses came back via courier about a month later; Felipe had

found them. Three months later, a friendly Bostonian smashed a window

in my minivan and took my backpack containing both sunglasses and

Samantha, my PowerBook 170 on which this entire travelogue was written.]

Felipe led us down a wet stream to the Rio Madrigal for a swim. The water was

a cool 76 degrees and I immersed myself up to my face, but didn't get cool. In

fact, sweat was still pouring out of my face even as I sat in the water. I

didn't want to get out, but it was 4:30 and sunset was fast approaching.

Walking down the river wasn't so bad. Thanks to Felipe's encyclopedic

knowledge of the area, we saw several Jesus Christ lizards skipping over the

water, observed a crayfish that he dug up, and ate some Hibiscus flowers that

tasted like watermelon.

Walking down the river wasn't so bad. Thanks to Felipe's encyclopedic

knowledge of the area, we saw several Jesus Christ lizards skipping over the

water, observed a crayfish that he dug up, and ate some Hibiscus flowers that

tasted like watermelon.

It was nearly sunset when we got down to the beach, but Felipe's energy was

undimmed. He scaled a coconut tree and brought down a bunch, then hacked them

open with the huge knife he carried on his hip so that we could drink the

milk.

It was nearly sunset when we got down to the beach, but Felipe's energy was

undimmed. He scaled a coconut tree and brought down a bunch, then hacked them

open with the huge knife he carried on his hip so that we could drink the

milk.

We still had to walk a little more than a mile back to the tent camp. Just

putting one foot in front of the other on the soft sand took all my energy. I

had a tough time admiring the sunset, the macaws, or the spider monkeys we saw

from the beach. I spent the evening under cold showers, drinking, and

generally feeling weak with a resting pulse of 90.

We still had to walk a little more than a mile back to the tent camp. Just

putting one foot in front of the other on the soft sand took all my energy. I

had a tough time admiring the sunset, the macaws, or the spider monkeys we saw

from the beach. I spent the evening under cold showers, drinking, and

generally feeling weak with a resting pulse of 90.

[I later developed a theory about why Corcovado seemed so oppressively hot.

Washington, D.C., where I grew up, actually records higher temperatures and

similar humidity. Yet I don't remember ever getting this enervated after

exercise there. I've concluded that it is much easier to tolerate a few hours

of heat and humidity if you spend the rest of the day and night air

conditioned. My body seems to have a long time constant. I don't mind the

cold in Massachusetts because I'm never out in it for more than a few hours.

The coldest weeks of my life were in Israel where they are too poor to heat

houses or restaurants. Being at 45 degrees 24 hours/day felt much colder than

being at 15 degrees for part of the day and 72 degrees the rest of the time.]

[I later developed a theory about why Corcovado seemed so oppressively hot.

Washington, D.C., where I grew up, actually records higher temperatures and

similar humidity. Yet I don't remember ever getting this enervated after

exercise there. I've concluded that it is much easier to tolerate a few hours

of heat and humidity if you spend the rest of the day and night air

conditioned. My body seems to have a long time constant. I don't mind the

cold in Massachusetts because I'm never out in it for more than a few hours.

The coldest weeks of my life were in Israel where they are too poor to heat

houses or restaurants. Being at 45 degrees 24 hours/day felt much colder than

being at 15 degrees for part of the day and 72 degrees the rest of the time.]

Monday, January 23, 1995

After a 6 a.m. breakfast, which was yet another in a series of

remarkably good meals considering the remoteness of the tent camp and the

reasonable prices, six of us walked up the beach to Carate. The sun was in our

faces and we were all sweating by the time we got to the airstrip. Early light

on the Pacific was beautiful though and flocks of pelicans entertained us by

fishing right on top of the breakers.

After a 6 a.m. breakfast, which was yet another in a series of

remarkably good meals considering the remoteness of the tent camp and the

reasonable prices, six of us walked up the beach to Carate. The sun was in our

faces and we were all sweating by the time we got to the airstrip. Early light

on the Pacific was beautiful though and flocks of pelicans entertained us by

fishing right on top of the breakers.

Ken, an artist from Seattle, shouted just after we took off.

Ken, an artist from Seattle, shouted just after we took off.

"Look at those turtle tracks!" Ken pointed down at the beach. Spotting turtles

nesting at night was just one of the popular Corcovado activities that we'd

failed to try. This was Chantal's favorite place in all of Costa Rica and she

was very sorry to leave after such a short time; I wasn't personally upset by

the idea of getting into the cool mountains. I would have liked to go out to

Caño Island, a famous spot for its snorkeling, turtle-watching, and

pre-Columbian cemetery, but there is currently no way to get there from Carate;

you have to start in Drake's Bay, the main tourist town in the area, which is

on the other side of the national park.

Continue on to Monteverde

Continue on to Monteverde

philg@mit.edu

Related Links

Add a comment | Add a link

We flew out of Tortuguero in the morning in a Cessna 180 that looked

decidedly old and downmarket after the Piper Twin. The flight was beautiful

and this time I "checked" the yellow river that Edgar had mentioned. We also

saw the highway that we'd taken on the way back from rafting the Pacuare.

Costa Rica is one rugged country and the only way to fully appreciate it is

from the air. We changed planes in San Jose and picked up another

single-engine Cessna for the flight to Carate. We climbed away from the local

airport, over shantytowns and estates, then coffee plantations, and then

stripped hillsides with cabins. The Central Valley has many charms, but not

much wilderness remains.

We flew out of Tortuguero in the morning in a Cessna 180 that looked

decidedly old and downmarket after the Piper Twin. The flight was beautiful

and this time I "checked" the yellow river that Edgar had mentioned. We also

saw the highway that we'd taken on the way back from rafting the Pacuare.

Costa Rica is one rugged country and the only way to fully appreciate it is

from the air. We changed planes in San Jose and picked up another

single-engine Cessna for the flight to Carate. We climbed away from the local

airport, over shantytowns and estates, then coffee plantations, and then

stripped hillsides with cabins. The Central Valley has many charms, but not

much wilderness remains.

Downtown Carate proved to be a pulperia next to the airstrip. The

nearest telephone is in Puerto Jiménez, a 90 minute drive around the

coast over a dirt road.

Downtown Carate proved to be a pulperia next to the airstrip. The

nearest telephone is in Puerto Jiménez, a 90 minute drive around the

coast over a dirt road.

After lunch, we hopped onto a couple of scrawny poky horses with Urbano as our

guide. Chantal hadn't been on a horse for eight years, but she took to her

mount, whom she dubbed "Matthew" because that was as close as she could get to

the Spanish name, with gusto.

After lunch, we hopped onto a couple of scrawny poky horses with Urbano as our

guide. Chantal hadn't been on a horse for eight years, but she took to her

mount, whom she dubbed "Matthew" because that was as close as she could get to

the Spanish name, with gusto.

Chantal stands next to a "walking tree," which actually can move several meters/year. Two second exposure.

Chantal stands next to a "walking tree," which actually can move several meters/year. Two second exposure.

We still had to walk a little more than a mile back to the tent camp. Just

putting one foot in front of the other on the soft sand took all my energy. I

had a tough time admiring the sunset, the macaws, or the spider monkeys we saw

from the beach. I spent the evening under cold showers, drinking, and

generally feeling weak with a resting pulse of 90.

We still had to walk a little more than a mile back to the tent camp. Just

putting one foot in front of the other on the soft sand took all my energy. I

had a tough time admiring the sunset, the macaws, or the spider monkeys we saw

from the beach. I spent the evening under cold showers, drinking, and

generally feeling weak with a resting pulse of 90.