The Dirty Dozen

reviewed by Philip Greenspun; January 2010

Site Home : Book Reviews : One Review

|

The Dirty Dozenreviewed by Philip Greenspun; January 2010

Site Home : Book Reviews : One Review |

This is a review of

The Dirty Dozen: How Twelve Supreme Court Cases Radically Expanded Government and Eroded Freedom,

by Robert A. Levy and William Mellor.

This book is very timely as the Congress is debating a massive federal intervention in the private health care market. Can the federal government force a private citizen who never travels outside his or her home state to purchase health insurance, something that would be used exclusively inside one state and that, due to government regulation, is available only within one state? Can the federal government exempt Nebraska residents from paying for Medicaid because a Nebraska senator's vote was necessary to get $1 trillion in spending approved? Can the federal government establish different tax systems for unionized workers and non-union workers, as Barack Obama and Congress have proposed? (Union workers would not be subject to a tax on the value of their health insurance; non-union workers would have to pay a tax.) If you've wondered about these issues, The Dirty Dozen is the book for you. It explains how the Supreme Court, mostly starting during the (first?) Great Depression began to reinterpret the Constitution to permit a vast expansion of federal power. Regardless of your political beliefs, it is very interesting to see how we got from Lincoln having to beg state governors for resources to the all-powerful federal government of today.

The book has hundreds of citations to original sources, but they are buried in the back of the book so that the general reader will not get bogged down in the scholarly details. Let's start with a book report-style summary of what's in The Dirty Dozen.

Section 8 starts with "The Congress shall have power To lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;".

This clause was central to the debate over whether the Social Security income distribution system could be constitutional, culminating in Helvering v. Davis in 1937. Here's what the authors say:

During the ratification debates, there were three main perspectives on the power to provide for the general welfare. The most expansive view, which neither Madison nor Hamilton advocated, is that Congress can serve the general welfare in whatever way it pleases -- even if no taxes are collected, and even if the Constitution contains no other specified authority. Essentially, Congress's powers would be nearly all-inclusive.

The second view, advocated by Hamilton, is that Congress could tax and spend to execute its enumerated powers as well as other powers -- provided only that the purpose of the tax is to promote the general (i.e., national) welfare, not the narrower (i.e., local) welfare of specially favored parties. In practice, however, the first and second views tend to merge. That's because the courts defer to Congress's determination whether a tax serves the "general" welfare, and because the execution of Congress's powers will almost always require money and, therefore, taxation.Only the third, Madisonian, view establishes any meaningful restriction on congressional enactments. Madison insisted that the General Welfare Clause did not empower Congress to do anything beyond those particular authorizations granted in the remainder of Article I, section 8. A broader interpretation, declared Madison, would make a mockery of the notion of limited federal government. If Congress had an independent power to tax for the general welfare, then the enumeration of its other powers, which also provide for the general welfare, would simply be excess verbiage. To the contrary, argued Madison, because the enumerated powers are those that serve the general welfare, the power to provide for the general welfare through taxation is synonymous with the power to tax in order to execute the enumerated powers.

...

Still, the politicians could not, by themselves, have irreparably damaged the Constitution. They needed, and they garnered, the active support of the Supreme Court. Together -- the Roosevelt administration, Congress, and the Court -- they turned the Constitution on its head. Instead of promoting a federal government possessing only those powers enumerated in the Constitution, the New Dealers promoted a government of nearly boundless powers, limited only by specific prohibitions in the Constitution. Nothing could have been further from the intent of the Framers.

During the Roosevelt era, the Supreme Court effectively re-wrote the Constitution. Many of the Court's mistakes are catalogued in other chapters of this book. If faced with identifying the worst of those mistakes, we would surely rank the Court's misreading of the General Welfare Clause high on the list. Seventy years have elapsed since Helvering and not once has the Court invalidated an act of Congress because it violated the General Welfare Clause. Yet the federal government has immersed itself in matters ranging from public schools to hurricane relief, drug enforcement, welfare, retirement systems, medical care, family planning, housing, and the arts -- not a single one of which can be found among Congress's enumerated powers.

...

Justice Sandra Day O.Connor's dissent [in South Dakota v. Dole (1987; a case relating to the feds establishing a 21-year-old drinking age nationwide)] was a pointed reminder of just how pernicious the precedent of Butler and Helvering had proven to be: "If the spending power is to be limited only by Congress' notion of the general welfare, the reality, given the vast financial resources of the Federal Government, is that the Spending Clause gives power to the Congress to tear down the barriers, to invade the states' jurisdiction, and to become a parliament of the whole people, subject to no restrictions save such as are self-imposed. This, of course, . was not the Framers' plan and it is not the meaning of the Spending Clause."

A lot of what the federal government does seems to violate the general welfare clause. Tariffs, subsidies, and regulations on agriculture, for example, benefit certain farmers and corporations within the agriculture industry, but they harm consumers with higher prices for food. Transferring money from a poor consumer to a rich farmer doesn't help the "general welfare" of the nation. Perhaps a state government could do it, but how can the feds do it? Let's look at the next chapter...

Article 8: "To regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes;"

The authors:

Roscoe Filburn operated a small farm in Ohio, producing milk, poultry, and eggs primarily. But he also grew a small amount of wheat, the bulk of which was used on his farm for feed, some of which he and his family consumed, and a small portion of which was sold within the state. The Department of Agriculture, under the direction of Secretary Claude C. Wickard, set Filburn.s 1941 wheat allotment at 11.1 acres with a yield of 20.1 bushels per acre. Filburn, however, planted a total of 23 acres and harvested an excess of 239 bushels. At a penalty of 49 cents a bushel, the excess subjected him to a total fine of $117.11.Filburn challenged the Agricultural Adjustment Act as, among other things, an invalid regulation of interstate commerce. No portion of Filburn's crop was sold in interstate commerce and the vast majority of it was consumed on his own farm.

In Wickard v. Filburn, the Supreme Court ruled that because Filburn's growing of wheat for personal use might affect the price of interstate wheat, the federales could tell him not to do it. The interpretation of Filburn has expanded over the years so that now the federal government can prevent a citizen from growing marijuana in his backyard for personal consumption, even though the interstate sale of marijuana is illegal and therefore the growing could not affect the price of a legally traded commodity. (Raich 2005)

The authors:

For more than 50 years following Wickard, no law was ever struck down for exceeding Congress's power under the Commerce Clause. The Interstate Commerce Clause became, and remains, the primary source of federal power. Among the many consequences of this shift has been the massive federalization of traditional state functions, particularly in the area of criminal law -- absurdly characterized as regulation of interstate commerce. This trend has been so widespread that no one seems sure exactly how many federal criminal laws exist. One recent estimate suggests that there are now more than 4,000 federal statutory crimes, covering an unimaginable variety of activities, from the most heinous crimes to the misuse of the "Smokey Bear" character or name. The number of federal regulations that may be enforced criminally is even more difficult to quantify, with estimates ranging from 10,000 to 300,000.

The first slight pushback after Wickard came in 1995 when the Supreme Court ruled in Lopez that the federal government could not regulate gun possession near schools; the matter had to be left to the states. This swing of the pendulum was mostly reversed in a 2005 decision in Gonzales v. Raich. Sandra Day O'Connor and Clarence Thomas were lonely dissenting voices: "If the Court always defers to Congress as it does today, little may be left to the notion of enumerated powers" (O'Connor); "Respondents Diane Monson and Angel Raich use marijuana that has never been bought or sold, that has never crossed state lines, and that has had no demonstrable effect on the national market for marijuana. If Congress can regulate this under the Commerce Clause, then it can regulate virtually anything.and the Federal Government is no longer one of limited and enumerated powers. ... If the majority is to be taken seriously, the Federal Government may now regulate quilting bees, clothes drives, and potluck suppers throughout the 50 States" (Thomas).

Business in the U.S. currently faces more regulatory uncertainty than at any time since the 1930s. What will tax rates be? Will there be special tax credits for people buying houses? For people buying cars? Will there be special taxes on certain industries, such as banking? New taxes on health insurance provided to employees? Will judges be able to rewrite private mortgage contracts? Nobody knows; these changes are entirely up to the whim of Congress and Barack Obama.

How much can a new government regulation possibly cost a business? The authors provide an example that will likely be chilling to investors:

It must have been nice to own a 143,000-square-foot office building on a prime downtown corner in a major U.S. city, fully leased, long-term, to a large insurance company. There was only one hitch. By law, no rent increases were allowed for six decades -- from 1933, shortly after the building was erected, until 1993, when the owner was finally able to obtain legislative relief. During that 60-year period, the lessee paid a mere $23,000 in annual rent -- about 20 cents per rentable square foot, compared to 1993 market rates of roughly $14 per square foot.Here's how it happened: Property owner John Trostel constructed the 14-story building in Des Moines, Iowa, in 1931, then leased it out for $23,000 annually, plus the usual leasehold expenses. Instead of a cost-of-living escalator, Trostel protected himself against inflation with a gold clause -- a common provision at the time -- which gave the lessor an option to demand payment in gold rather than dollars. Big mistake. Trostel never figured that two years later, in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal Congress would abrogate all gold clauses, ostensibly to maintain government reserves of the metal during the economic emergency of the Great Depression.

Rescinding private contracts was deemed necessary because of an economic emergency. The same question had come up in the context of restricting civil liberties during the Civil War and Justice David Davis wrote "The Constitution of the United States is a law for rulers and people, equally in war and in peace, and covers with the shield of its protection all classes of men, at all times, and under all circumstances. No doctrine, involving more pernicious consequences, was ever invented by the wit of man than that any of its provisions can be suspended during any of the great exigencies of government." Davis's words did not persuade FDR's court. In a dissent in Blaisdell (1934), Justice Sutherland wrote "If the provisions of the Constitution be not upheld when they pinch, as well as when they comfort, they may as well be abandoned."

We consider ourselves to offer a more stable legal environment than Argentina and Brazil, but perhaps that is only because we haven't been tested as sorely.

Article I: "All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States." This chapter of The Dirty Dozen covers the question of whether Congress can delegate its lawmaking powers to administrative and Executive Branch agencies.

The authors:

First, however, let's consider the scope of the problem. Perhaps you are familiar with the Federal Register. It's published every day and provides notice of executive orders as well as actual and proposed new rules by the various federal regulatory agencies. During the 12-month period ended March 31, 2006, the Federal Register contained an astonishing 77,537 pages. At the beginning of each calendar quarter, the executive orders, rules, and regulations in the Federal Register that become final law are included in the Code of Federal Regulations. If you were to purchase a current edition of the CFR from the U.S. Government Printing Office, you would need enough shelf space for more than 200 bound volumes. By comparison, the entire U.S. Code, which contains all of the laws passed by Congress and signed by the president, requires roughly 35 volumes -- about one-sixth the number devoted to the CFR. ... As of mid-year 2005, the CFR comprised rules and regulations from 319 independent and executive agencies. The upshot: an alphabet soup of bureaus run by anonymous bureaucrats who tell us how to live our lives."

More regulation is not necessarily bad for everyone. It may make the U.S. a less attractive place to do business than a foreign country, but within the U.S. it may benefit some: "Along those same lines, a recent study for the Small Business Administration revealed that small firms pay disproportionately to cope with excessive regulation. For firms with more than 500 employees, the cost per employee to comply with environmental laws was $717 annually. Firms with fewer than 20 employees spent more than six times as much; their annual compliance cost per employee was $3,228."

The authors pick out the FDA as the "one agency that exemplifies the problems inherent in delegated power". Congress told the FDA to allow only those drugs "proven safe and effective" but "For all intents and purposes, Congress has left it to the FDA to determine the degree of safety and efficacy, the level of certainty required from investigators, the quantity and quality of data to be examined, the meaning of 'substantial evidence', and the criteria for reaching conclusions 'fairly and responsibly'. By relinquishing its lawmaking function, Congress gave the FDA both latitude and incentives to delay drug approvals unnecessarily. And by allowing unelected bureaucrats to exercise such power, Congress left the public without an effective means to protest."

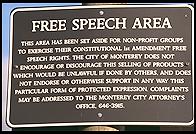

The First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech. Politicans, however, have made it illegal to spend a lot of money on political speech, e.g., advocating that incumbent politicians be replaced. An ad encouraging people to eat Big Macs has more legal protection than an ad detailing the tax money and other favors that a politician has handed out to his buddies.

As a resident of a one-party state (Massachusetts), I have no personal interest in this chapter. Assured that a Democrat will win, both Republicans and Democrats typically do not waste effort campaigning or advertising here. The authors, however, grabbed my attention with the absurdity of some of the rules: "Interestingly, the new BCRA regulations do not apply to print ads, Internet blogs and magazines, news stories, commentary, or editorials aired by media companies. The Court explained that 'reform may take one step at a time,' and went on to rationalize that a 'valid distinction... exists between the media industry and other corporations that are not involved in the regular business of imparting news to the public'. In other words, a non-media corporation may not pay for electioneering communications -- unless, of course, it becomes a media corporation by acquiring a newspaper or radio/TV station, in which case unrestricted spending on commentary or editorials is somehow justified."

More or less every new law and regulation seems to assist current politicians in their quest to continue enjoying power and receiving a government paycheck: "Instead of preventing corruption -- or even the appearance of corruption -- the real effect of the regulations upheld in McConnell (2003) and Buckley (1976) has been to protect incumbents from upstart challengers. The careers of sitting politicians can more easily be perpetuated if the speech of their opponents can be repressed."

In Citizens

United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), the Supreme Court

turned back the tide of government suppression of political speech by

ruling that the Federal Election Commission should not have been able

to suppress a film critical of Hillary Clinton. How did the incumbents

take this? "This ruling opens the floodgates for an unlimited amount

of special-interest money into our democracy," President Obama

said. "This ruling strikes at our democracy itself." [For a more

articulate argument against allowing corporations to participate in our democracy, watch

The Corporation,

a very thoughtful Canadian movie that explores the effects of powerful actors

in an economy or society being constrained to seek maximum profits by

any legal means (imagine a Michael Moore movie made for a critical audience)--the movie can be found on

hulu (free... with ads from big corporations).]

Second Amendment: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed." The authors dispense with the argument that this allows only militia members to have guns by asking what if the amendment said "A well-educated Electorate, being necessary to self-governance in a free State, the right of the people to keep and read Books, shall not be infringed"? Would we then say that only registered voters would have the right to read? The authors: "If the Second Amendment truly meant what the collective rights advocates propose, then the text would read, 'A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the States to arm their Militias, shall not be infringed'."

The book reminds us that we can't always rely on the police to protect us. The Virginia Tech shooting is used as an example:

A bill, introduced on behalf of the Virginia Citizens Defense League, would have overridden university rules and given properly licensed students and employees the right to carry handguns on public college campuses. The bill died in the Virginia General Assembly, 15 months before the April 2007 bloodbath. Virginia Tech spokesman Larry Hincker was pleased with the outcome at the time. "I'm sure the university community is appreciative of the General Assembly's actions because this will help parents, students, faculty and visitors feel safe on our campus."

Seung-Hui Cho, the Virginia Tech killer, shot his first victims at 7:15 am in a dormitory. The police failed to find Cho, cancel classes, evacuate the campus, or notify the parents of one wounded girl (who died three hours later). Two hours later, Cho entered another building where classes had begun and shot a few dozen more people. Concerned about their own safety, police did not enter the building until Cho was nearly done with killing his 32nd victim.

Most of the federal restrictions on gun possession stem from United States v. Miller (1939). The authors remind us that this case was decided by judges who had heard only from the federal government's lawyer; the men accused of possessing guns were not represented before the Supreme Court due to lack of funds and time: "In any event, Miller and Layton were unable or unwilling to defend themselves on appeal, especially within impossible time constraints. Neither defendant showed up before the Supreme Court; they had no written brief to support them, and no legal representation at oral argument. The Court did nothing to appoint other counsel or re-schedule the case. Instead, Justice McReynolds produced a muddled opinion that has confused lawyers, law students, judges, and the public for almost seven decades. When it was all over, the Supreme Court reversed the lower court's holding that the National Firearms Act violated the Second Amendment. Justice McReynolds ruled that only those weapons related to militia use were protected by the Amendment."

Gun ownership advocates finally won a limit on federal power to restrict: District of Columbia v. Heller (2008; handed down after The Dirty Dozen was written, but addressed in the latest paperback edition).

Fifth Amendment: "No person shall be ... deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law."

This chapter concerns Korematsu v. United States (1944), which allowed the Roosevelt Administration to intern Japanese-Americans. The case has never been overturned.

Dissenting Justice Robert H. Jackson cautioned that "guilt is personal and not inheritable". By condoning Korematsu's mistreatment, he continued, "the Court for all time has validated the principle of racial discrimination ... The principle then lies about like a loaded weapon ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need ... [Each] passing incident becomes the doctrine of the Constitution."

The authors remind us that a handful of Americans did oppose the

internment: "J. Edgar Hoover thought that alleged sabotage by Japanese

Americans should be handled on a case-by-case basis, requiring

probable cause to take action and proper judicial processes. Senator

Robert Taft, the conservative Republican from Ohio, was alone in

objecting on the Senate floor to enactment of Public Law 503, which

was then passed by voice vote." The authors then quote Peter Irons, author of

Justice at War: The Story of the Japanese-American Internment Cases:

"Roosevelt's desire for partisan advantage in the 1944 elections

provides the only explanation for the delay in ending internment.

Political pressure influenced the evacuation and internment debates in

1942, and political concerns held up the release of Japanese Americans

almost three years later. Between these two episodes, they received a

cruel and unnecessary civics lesson in the power of politics to

dictate military and judicial decisions."

The authors draw parallels between the Korematsu case and the detention of Jose Padilla, a U.S. citizen accused of planning Islamic terrorist attacks in the U.S. Padilla was detained for years without trial:

We cannot permit the executive branch to declare that a U.S. citizen is an enemy combatant, whisk him away, detain him indefinitely without charges, deny him legal counsel, and prevent him from arguing to a judge that the whole thing is nothing but a mistake. ...

Suppose, however, President Bush had released Padilla, who proceeded to blow up parts of New York. The potential for such tragedies exists whenever anybody is discharged for lack of evidence, then commits a crime. In the case of suspected terrorists, the stakes are immense. So a powerful argument can be made for changing the rules and establishing a preventive detention regime -- tilting toward national security even though some civil liberties might be compromised. But if we do change the rules, the process cannot be implemented by executive edict without congressional or judicial input. And it cannot be law on-the-fly, with no knowledge of the rules by anyone other than the executive officials who are responsible for their enforcement.

Fourteenth Amendment: "[N]or shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law."

This chapter covers one of my favorite subjects: civil forfeiture. The authors explain that it was originally designed for piracy and smuggling. The U.S. government would want to punish a guy in France for smuggling, but had no practical way to reach the person so it would take the guy's ship, which was in a U.S. port. "During the Civil War, however, civil forfeiture laws were released from these historical moorings. The Confiscation Acts allowed the Union to seize and forfeit the rebels' Northern property and the property of those who aided the Confederacy. When the Supreme Court upheld these acts against constitutional challenges, it worked 'a revolution in forfeiture law that persists to this day'."

The authors lay out of the facts behind Bennis v. Michigan, in which the government's seizure of an automobile was ruled constitutional:

In September 1988, John and Tina Bennis bought a second car, an 11-year old 1977 Pontiac. The couple, who were both employed, had split the $600 cost of the Pontiac. ... Three weeks later, on October 3, 1988, Detroit police witnessed a woman "flagging" passing vehicles on the corner of Eight Mile and Sheffield, an area known for prostitution. Soon thereafter, they witnessed a 1977 Pontiac slow to a stop and allow the woman to enter. The police followed the Pontiac until it stopped again. Upon approaching the vehicle, they witnessed the woman, a recidivist prostitute, performing a sex act on the driver, John Bennis. Mr. Bennis was arrested and later convicted of gross indecency. ... Simultaneous with the criminal charges against John Bennis, the county prosecutor brought a [successful] forfeiture action under a Michigan statute that allowed for the confiscation of property used for the purpose of "lewdness, assignation or prostitution."

Basically the wife suffered three times: her husband spent their money on a hooker; she probably had to spend some family money to defend her husband against the criminal charges; she lost her car, despite the fact that there was no evidence that she authorized its use for prostitution. The authors discuss some changes in the direction of greater rights for property owners since the Bennis decision, but basically both federal and state governments have the right to take your stuff and make you sue them to get it back, even when you have not been convicted of any crime.

Fifth Amendment: "[N]or shall private property be taken [except] for public use..."

The authors describe how in the old days "public use" meant something like a road that everyone could use. There has been a drift starting in 1954 with Berman v. Parker towards allowing municipalities to take private land and hand it over to commercial developers with the goal of increasing property tax revenues.

... some governments pushed even further to seize well-maintained property in the name of .economic development.. Initially they condemned slums, then blighted areas, then not very blighted areas, then perfectly fine areas. The Michigan Supreme Court's Poletown opinion in 1981 was the first to sanction this new trend. In that case, the city of Detroit took an entire neighborhood that everyone admitted was not blighted on the grounds that expansion of the nearby General Motors plant would create "public benefits" in the form of higher tax revenue and more jobs. The Michigan Supreme Court bought this argument, ruling that eminent domain could be used for public benefit. Detroit soon discovered that the closely knit community could not be replaced, and the plant did not live up to its promise of bringing economic prosperity to the city.

The recent landmark case is Kelo v. City of New London (2005), in which the city condemned Suzette Kelo's house in order to hand it over to developers whom they expected to pay an additional million dollars per year in property tax. This turned out to be legal, according to the Supreme Court. It did not help the town of New London, though, because the development scheme fell apart in the Collapse of 2008-? and the big employer, Pfizer, left town. Sandra Day O'Connor dissented from Kelo:

"Any property may now be taken for the benefit of another private party, but the fallout from this decision will not be random. The beneficiaries are likely to be those citizens with disproportionate influence and power in the political process, including large corporations and development firms. As for the victims, the government now has license to transfer property from those with fewer resources to those with more. The Founders cannot have intended this perverse result."

This chapter chronicles courts' attempts to determine to what extent the government may render a property owner's interest less valuable by regulation, i.e., when is the Fifth Amendment's "[N]or shall private property be taken ... without just compensation" injunction violated. The chapter describes Penn Central v. New York City (1978) and Tahoe-Sierra (2002). In Tahoe-Sierra, the local government decided to achieve some environmental goals by stopping all new development. The government said that it wasn't a "taking" because the restrictions were temporary:

In a triumph of form over substance, Tahoe-Sierra gives legislatures virtually free reign to deprive property of its entire value for an unlimited amount of time without compensation, provided they style each successive deprivation as .temporary. in nature. As Justice Clarence Thomas correctly pointed out in dissent, "[T]he 'logical' assurance that a 'temporary restriction' ... merely causes a diminution in value,' .. is cold comfort to the property owners in this case or any other. After all, 'in the long run we are all dead'." This observation is not hyperbole; writing shortly after Tahoe-Sierra was decided, one legal scholar noted, "Of the 700 or so ordinary people who started on this journey, 55 have since died."

As it stands, there are basically no restrictions on government action. If you design and build a beautiful house, then want to knock it down and build something that fits your lifestyle better, the government can say "You built such a beautiful house that we are giving it landmark status and you can never touch it", even if that renders the property valueless.

Ninth Amendment: "The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people".

In Nebbia v. New York (1934), the Supreme Court allowed a state to prevent a merchant from selling milk for less than a set minimum price.

At the behest of dairy interests, Congress passed a law banning interstate shipment of "filled milk", a relatively cheap canned milk in which the butterfat had been replaced with vegetable oil. An Illinois company continued to make the product and sell it within Illinois, but was charged with violating the Filled Milk Act. In U.S. v. Carolene Products Co. (1938), the government's right to shut down the company was upheld.

The authors:

Carolene Products represented the beginning of a two-tiered approach to enforcing rights. Those rights that had -- fortunately -- been specifically enumerated would receive meaningful protection. But unenumerated rights, like the right to enter into contracts or the right to practice a trade, would receive only "rational basis" scrutiny. Sadly, the Court has repeatedly reaffirmed that holding and, with each iteration, the language of the test has become more and more deferential to government power.

...

Justice William O. Douglas, one of the leading liberals of the twentieth century, described the right to work as "the most precious liberty that man possesses" and eloquently defended it: "Man has indeed as much right to work as he has to live, to be free, to own property... It does many men little good to stay alive and free and propertied, if they cannot work. To work means to eat. It also means to live. For many it would be better to work in jail, than to sit idle on the curb. The great values of freedom are in the opportunities afforded man to press to new horizons, to pit his strength against the forces of nature, to match skills with his fellow man.

Like all rights, the right to earn an honest living is meaningful only if it can be enforced and protected. Thanks to the inclusion of the Bill of Rights, the Constitution provides Americans with two layers of protection: the enumeration of powers, which constrains the ends that the federal government may seek, and the Bill of Rights, which constrains the means by which the government may pursue those ends. During the New Deal, both of these layers of protection came under attack. By condoning a vast expansion of government powers (see especially Chapters 1 and 2), the Supreme Court allowed Congress to pursue virtually any ends. And by ignoring the mandate of the Ninth Amendment, the Court allowed Congress to employ virtually any means.

The authors note that entry into roughly 20 percent of America's jobs is restricted in some way by local or federal government. You may purchase the finest automobile manufactured, but you cannot legally offer taxi rides in New York City. A woman who wanted to teach African hair braiding in Mississippi was required to take 3200 hours of classes before being licensed.

With no legal support for economic liberties, the door is wide open for special interests:

Consider this pronouncement from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, upholding an Oklahoma law requiring anyone who sells caskets to become a licensed funeral director. The court brushed aside the blatantly protectionist motives for the law, observing "while baseball may be the national pastime of the citizenry, dishing out special economic benefits to certain in-state industries remains the favored pastime of state and local governments."

Fourteenth Amendment: "[N]or shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

The set of amendments to the Constitution that were passed after the Civil War were intended to prevent states from discriminating on the basis of race. However, in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003) and UC v. Bakke (1978), the Supreme Court allowed state-run universities to admit students on the basis of race.

The Dirty Dozen

appears at a time when the economy is shrinking and the government is

growing. This mean that the government's share of the economy is

trending up toward 50 percent (chart). With

roughly half of the actions in the U.S. taken by someone working for the

government, inevitably there will be a lot of debate about what the

government can or should do.

Given that the Constitution is written in plain language and that politicians and Supreme Court justices are generally intelligent people, how did end up with a plainly Unconstitutional federal government? Let's see if we can accept these assumptions about human nature:

The biggest shifts toward more federal power came during perceived emergencies, such as the Great Depression or World War II. A majority of the nine human justices who make up the Supreme Court panicked. The Constitution was an okay document for normal circumstances, but the Framers never envisioned this crisis. Not everyone panics in an emergency, which is why there were always dissenters from the decisions that allowed the federal government to go well beyond the enumerated powers.

Let's consider why people involved in the federal government, both in Congress and the Executive branch, might want to expand beyond the enumerated powers. Suppose that someone offers to give you $1 trillion to improve public education in the U.S. It is natural to think of your capabilities and all of the great things that you could do with $1 trillion to spend. It would not be human nature to step by and say "I wonder what the people or the individual states would have done if we'd left the $1 trillion in their hands." If you did have second thoughts, you'd reflect on how much smarter you were than the average person and therefore more capable of spending money wisely.

Supreme Court justices are appointed by presidents. Aside from Ronald Reagan, it is tough to think of a President who didn't think that he could do a tremendous amount of good if only Congress would give him some more money to spend and some extra power. So if I were President I probably wouldn't nominate anyone for the Supreme Court unless I thought he or she to be sympathetic to expanded Executive and Federal power.

Finally we have stare decisis, the doctrine that judges should refrain from overturning previous decisions. A decision that came out of the Great Depression or World War II will stand for decades or centuries. Jimmy Carter created the U.S. Department of Education. Ronald Reagan could not imagine how interfering with state and local government-run schools could be one of the federal government's Constitutional powers or a wise use of public funds, so he tried to kill it but Congress wouldn't let him. The department's Web site today says "ED currently administers a budget of $62.6 billion in regular FY 2009 discretionary appropriations and $96.8 billion in discretionary funding provided under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009--and operates programs that touch on every area and level of education." We devote more than 1 percent of U.S. GDP, which is more than the combined military budgets of France, Germany, the U.K., Canada, et al, to a bureaucracy that educates no children and whose spending has not resulted in cost cuts at the state and local level. How did the U.S. survive for more than 200 years without this department? We dare not imagine and therefore we dare not stop this $159 billion/year bleed.

We've gotten to a point where federal law touches almost every aspect of daily American life. Primarily due to immigration, the U.S. population is forecast by demographers to be somewhere between 600 million and 1 billion in 2100. That means that a citizen wishing to get a law changed will be one voice among 1 billion and may live 3000 miles away from the nearest decision-maker. This could not be farther from what the framers of the Constitution envisioned.

The Framers envisioned something much more like the present-day European Union. A citizen would live under laws made locally but use currency minted centrally. Consider a citizen of Ireland. He or she has one voice among 4.5 million for most of the laws and regulations that affect daily life. Our Dublin resident uses currency and weights and measures that are common to a large region.

The Dirty Dozen

makes it abundantly clear that the Constitution has been stretched to

accommodate a federal government vastly more powerful and intrusive

than the Framers would have considered legal. If we decide that we

like or need a huge federal government, perhaps it is time to rewrite

the Constitution thoughtfully. In a new constitutional convention, we

could decide if we want to keep our unusual legislative/executive

system or adopt a more conventional parliamentary system. We could

simplify our criminal justice system by eliminating the dual tracks of

state and federal statutes and prisons; there would be a single

criminal code for the entire U.S. We could eliminate educational

opportunity disparities among states by having federally funded and

operated public schools, eliminating the current system in which the

federal government mandates or nags and the states are supposed to

implement. We could have uniform gun laws across all states, codified

in the new constitution. We could have federal licensing for

physicians, health insurance, and other components of the health care

system that are, in any case, now substantially funded with federal

tax dollars.

Right now we are basically trying to run a China-like government with a European Union-style constitution.

The authors of The Dirty Dozen

come down pretty strongly against rewriting or reinterpreting the

Constitution to allow the U.S. federal government to operate like the

central government of the People's Republic of China. They advocate a

restoration of state and individual rights, at least back to where we

were circa 1925. Even if you don't agree with their political ideas,

the book makes for interesting reading. Nearly all legal scholars

would agree that these are 12 of the most important cases ever to come

before the Supreme Court and that they have changed our lives

immeasureably. The authors capably summarize the reasoning behind the

majority decisions even though their sympathies are with the dissent.

Considering the technical subject, the book is remarkably easy to read. I got through most of it on a commercial airline flight.