Film Recommendations

by Philip Greenspun; created 1996

Site Home : Photography : Film Recommendations

by Philip Greenspun; created 1996

Site Home : Photography : Film Recommendations

Color slides make you feel like a hero. Slides viewed on a light table have

much more tonal range than a print viewed with reflected light. Also, your images

won't be ruined by the slings and arrows of outrageous automated printing

machines.

Color slides will sometimes result in heartbreak because they offer so little exposure latitude. If you are a little over, you've lost detail in those highlights that a color negative film would have preserved.

Slides are good if you want to sell to traditional magazines and stock agents. Oh, and if you want to sound like a pro, refer to slide film as "E6" (after the Kodak process that is used to develop all slide film today except Kodachrome (K14) and infrared Ektachrome (E4)) or "chromes".

Slide films are sold in two broad categories: "professional" and "consumer".

Consumer film is produced so that it will look its best after a few months of

aging at room temperature. In theory, professional film is produced so that it

gets shipped from the factory when its color balance is perfect. It is designed

to be exposed immediately or refrigerated. In practice, the consumer and

professional versions of the same film usually produce indistinguishable

pictorial results. Fuji Velvia is sold as professional film in the United States

where amateurs have abandoned slides. People watch the shop pull the film

reverently out of the fridge and read the "refrigerate me" on the box and wring

their hands if they leave the film in a spare camera body for a few months. In

Europe, where amateurs still give slide shows, the same film is sold as a

consumer film with no refrigeration in the store and none indicated for longer

term keeping.

Why do professionals uncomplainingly pay a few dollars more per roll? Partly

for guaranteed consistency. They'll buy 100 rolls from the same emulsion batch,

test a couple to see exactly what in-camera filtration will result in neutral

gray, then photograph an entire clothing catalog with that batch. Sometimes Kodak

and Fuji don't bother getting a professional batch exactly neutral because they

expect professionals to test and use color correction gels. In those cases, you

actually get better results with consumer film. Another reason professionals buy

professional film is that they want an old emulsion like Kodak EPP that is

technologically obsolete. Kodak doesn't make it anymore for consumers because

their new T-grain slide films are dramatically better. But if you and your

catalog printer know exactly how to maintain color fidelity from the clothing to

the printed page with EPP then you aren't going to want to switch film just to

get finer grain (especially since you are probably using 120 or 4x5 size and not

enlarging much).

If you are only exposing one roll at a time and don't have any special

expertise with a particular emulsion, there are only two real benefits to

professional slide film. First, pro film comes in more flavors than consumer

film. Kodak in particular seems to release its professional slide films in

"neutral" and "warm color balance" versions. The same film packaged for consumers

comes in only one color balance. The second real benefit to professional film is

only for those who cling to old-style retouching methods (i.e., not PhotoShop).

Sometimes the professional version of an emulsion has a coating on the base side

to facilitate traditional retouching.

Should you happen to be using professional film, don't obsess over keeping it refrigerated. If you end up leaving it at room temperature for a few months, then what you end up with is consumer film. Which is more or less the same thing.

Note: If you do refrigerate your film, make sure that you do obsess over letting it come up to room temperature in its sealed container before using it. If you pull film out of the fridge and start using it immediately on the beach in Florida, you'll find that water condenses in little droplets on the film, leaving unsightly blotches on your processed images. From the 55-degree fridge to a 70-degree room, Kodak recommends about 1 hour for 35mm film, 30 minutes for 120, and 2 hours for a 50-sheet box of 4x5 film. Double these times if you've been keeping your film in the freezer. I'd also double them if you intend to use film outdoors on a hot day. I've been a bit sloppy with these times myself and never gotten burned with Kodak or Fuji film, but had some Agfapan 25 experiences that were horribly painful.

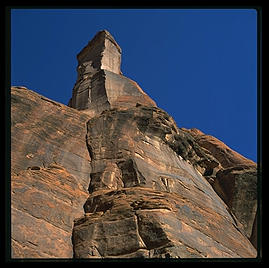

ISO 50. Incredible color. Saturated and yet still capable of subtlety. My

favorite for scenery. Can do violence to flesh tones, although allegedly Fuji is

working on this problem. I used this film almost exclusively in

Travels with Samantha.

Example: Parco dei Mostri (Park of Monsters) below the town of Bomarzo, Italy (1.5 hours north of Rome). This was the park of the 16th century Villa Orsini and is filled with grotesque sculptures. Rollei 6008, Zeiss 50mm lens, tripod, 120 size film. Reciprocity correction is minimal.

All three are good all-around slide films with extremely fine grain and saturated

yet fairly accurate color. The Kodak E100SW version is allegedly warmer than the

E100S. If you want to save money and need a huge pile of film, Fuji Sensia II and

Kodak Elite 100 are the consumer versions of these films.

All three are good all-around slide films with extremely fine grain and saturated

yet fairly accurate color. The Kodak E100SW version is allegedly warmer than the

E100S. If you want to save money and need a huge pile of film, Fuji Sensia II and

Kodak Elite 100 are the consumer versions of these films.

Example (right): Fuji Astia. two MIT professors at our 1998 graduation, Canon EOS-5, 17-35/2.8L.

Below: a few images from The Game, taken with Fuji Astia in my studio.

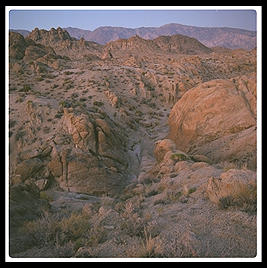

Below: some Kodak E100S fed through my Canon system near the Oregon/California border.

Below: Fuji Provia F (fine-grain) in Florida:

Kodak has great marketing for its E200 slide film. I used a lot of it at MIT's 1998 graduation ceremony and the results were pretty bad compared to those obtained with Fuji Astia shot on the same day. Fuji has its MS 100/1000 "multispeed" E6 film but I haven't tried it.

I've never found a decent ISO 400 slide film. The grain is intolerably intrusive. A lot of pros use Kodachrome 200 pushed. I haven't tried Fuji Provia 400 but I don't think it is a lot better than the T-grain Kodak Elite 400, which I tried in 1993 and found wanting. I recommend using ISO 400 negative film.

Example: from Chapter XII of Travels with Samantha.

Scotch 640 is remarkably awful. Avoid it; Kodak's 320T pushed 1 stop looks far better. Kodak's 160 and 320T films are pretty darn good.

Color negative film is very tolerant of exposure errors. You can be off by 2 or 3 f-stops and still get a print that is barely distinguishable from one from a correctly exposed negative. This frees your mind to concentrate on composition, focus, timing, etc.

Color negative film never gets very dark and therefore is good for CCD scanners, e.g., all desktop machines and also the scanners for PhotoCD workstations.

Pro lingo for negative or "print" film is "C41" (official Kodak name for the development process). If you have always wondered "Why does negative film have an orange color?" then this is the link for you.

Because a negative is never the final product and there is so much slop in the printing process, there isn't as much demand for "professional" print film as there is for "professional" slide film. Professional negative film tends to be produced for wedding photographers who want low contrast and photojournalists who want to push-process their C41.

Every 1 hour lab

in the world knows how to print this film accurately, which is an important

selling feature. Excellent sharpness and color. Some of my friends swear that

Fuji Super G 100 is better, especially for skin tone, and they're probably right

but I don't use a lot of ISO 100 print film.

Every 1 hour lab

in the world knows how to print this film accurately, which is an important

selling feature. Excellent sharpness and color. Some of my friends swear that

Fuji Super G 100 is better, especially for skin tone, and they're probably right

but I don't use a lot of ISO 100 print film.

Example: Rollei 6008, Zeiss 120mm macro lens, extension tube, tripod. Hilo, Hawaii 1990. (120 size film.)

ISO 160 low contrast films. These are designed for weddings where the groom wears black and the bride wears white and you want some detail in both fabrics. Also nice for smoothing out skin blemishes. One of the great things about these films is that labs in every corner of the world know how to make beautiful portrait prints from them. Fuji NPS is probably preferred if you expect mixed or fluorescent lighting.

For most people, most of the time, this is the correct speed color negative film to use. Whether you go Kodak or Fuji, you'll be amazed at how fine grain and color saturated the images are. Enlargements to 11x14 from 35mm look pretty good. My personal favorites in this category:

Example: Fuji Super G+ ISO 400. Canon EOS-5, 70-200/2.8 lens at f/4 and 1/125, fill flash set to -1 stop. Manhattan 1995.

I like NPH for general outdoor photography as well. For example, here are some pictures taken on a bright Florida day. Notice how the colors aren't pushed to the extremes as with most consumer film:

A few snapshots from Japan and China...

Photojournalists are heavy users of ISO 800 color negative film. Grain is acceptable if you don't enlarge beyond 5x7. Contrast and color saturation are surprisingly good. Kodak competes in this market with a variety of confusingly named products, e.g., Kodak Gold MAX. But Fuji seems to have the quality edge and that's what everyone uses.

I'm not sure why Black and White film makes sense any more. When I want black and white, I can just choose "desaturate" in PhotoShop and it is done. Still, if you want to work with traditional processes (i.e., you don't want to scan) and you want a negative that will last for hundreds of years, black & white is the way to go.

Great for scenery. You're going to need a tripod anyway to take those Ansel Adams-esque shots, so you might as well get the finest grain you can.

ISO 50. Very fine-grain. Good for studio use.

My first few rolls of this new C41-process film have made me think that it is

time to stop using TMAX-100. Ilford started what they thought would be a

revolution with XP1 and XP2, black and white films with extremely wide latitude

that could be run through any One-Hour lab in the world. Unfortunately, a lot of

people (including me) couldn't figure out how to get the pictures that we wanted.

In terms of contrast and density, TMAX-400 CN seems to behave more like a

standard B&W film except that it has very fine grain (finer even than

TMAX-100) and can be processed anywhere that color negative film can be.

My first few rolls of this new C41-process film have made me think that it is

time to stop using TMAX-100. Ilford started what they thought would be a

revolution with XP1 and XP2, black and white films with extremely wide latitude

that could be run through any One-Hour lab in the world. Unfortunately, a lot of

people (including me) couldn't figure out how to get the pictures that we wanted.

In terms of contrast and density, TMAX-400 CN seems to behave more like a

standard B&W film except that it has very fine grain (finer even than

TMAX-100) and can be processed anywhere that color negative film can be.

Caveat: TMAX-400 CN probably won't have the archival stability of "real B&W

film". You'll have to take more care in storing the negs (see

the Wilhelm book for how standard color

negs fare) and should probably make high-res scans of priceless images.

Caveat: TMAX-400 CN probably won't have the archival stability of "real B&W

film". You'll have to take more care in storing the negs (see

the Wilhelm book for how standard color

negs fare) and should probably make high-res scans of priceless images.

If you click on this thumbnail (or the one at to the upper right), you'll be offered the option of viewing a FlashPix. This was made from a 4000x6000 pixel ProPhotoCD scan and you ought to be able to get a good idea of the underlying film's properties.

More samples of TMAX 400 CN: in my Cape Cod photo essay. Very similar competitor: Ilford XP-2 Plus.

Introduced in 1954.

Classic look. Nice contrast. Grainy but consistently so and people like the look

of Tri-X grain. Confusingly, Kodak actually markets two very different emulsions

under the "Tri-X" name. The first is "Tri-X Pan": ISO 400, available in 35mm and

120, much mid-tone separation and not much highlight separation. The second is

"Tri-X Pan Professional": ISO 320, available in 120 and 4x5 sheets, not much

mid-tone separation and enhanced highlight separation (allegedly better for

studio lighting). When people talk about "Tri-X", they generally mean the ISO 400

Tri-X Pan that was made famous by photojournalists using 35mm cameras.

Introduced in 1954.

Classic look. Nice contrast. Grainy but consistently so and people like the look

of Tri-X grain. Confusingly, Kodak actually markets two very different emulsions

under the "Tri-X" name. The first is "Tri-X Pan": ISO 400, available in 35mm and

120, much mid-tone separation and not much highlight separation. The second is

"Tri-X Pan Professional": ISO 320, available in 120 and 4x5 sheets, not much

mid-tone separation and enhanced highlight separation (allegedly better for

studio lighting). When people talk about "Tri-X", they generally mean the ISO 400

Tri-X Pan that was made famous by photojournalists using 35mm cameras.

Remarkably fine-grained film for its speed (a true ISO 1200, designed for push processing). Here is an image exposed at ISO 1200 with a Fuji 617 camera:

Really only an ISO 800-1000 film that is designed for push processing to 3200 or 6400, this is great for experimenting with grain. I like to have it developed by Kodalux (with an $8 DP-36 mailer).

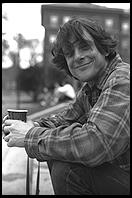

Example at left: George in front of Charles River. Red (25) filter. Nikon 8008, 20/2.8 AF lens, f/8 and be there.

You basically have a choice of two emulsions here: (1) Kodak High Speed Infrared; (2) Konica Infrared 750. Konica is slower, has a narrower spectral response and results in higher contrast, finer grained images. I don't really have enough experience with this art form to say too much. I recommending reading Laurie White's excellent Infrared Photography Handbook.

All of the preceding films are "pictorial" or "general-purpose" designs. They have the appropriate amount of contrast to pleasingly render the average scene. Fuji and Kodak (especially) make a long list of special-purpose films. These are good for

Some of these special purpose films are described in the Kodak Professional Photo Guide. Another good resource is the book Copying and Duplicating. The biggest and most competent photo retailers will stock special-purpose films in 4x5 sheets, in 100-foot rolls, and sometimes in 36-exposure canisters for 35mm cameras.

Try to buy film from a professional camera shop. These shops have fresh inventory and keep most of their stock in large refrigerators. If you want to save money, don't try doing so by bulk loading your own rolls. It is too difficult to avoid getting dust inside the canisters. However, buying gray market film from one of the large New York retailers, e.g., Adorama, is a reasonable way to economize.