Here’s a report from Las Vegas on things relevant to Pilatus pilots that were announced, presented, or discussed at NBAA.

The Pilatus PC-12 is close to the bottom end of what constitutes a “business aircraft” these days. New regulations tend to be applied across all sizes of aircraft and thus every regulation lifts the cost of operating a light aircraft closer to the cost of operating a Gulfstream. “Go big or go home” has cause nearly all of the very light jet designs to fizzle. The PC-12 has some unique capabilities, however, such as being able to operate from short, dirt, and/or grass runways, and therefore was more prominent at NBAA than similarly priced turbojets.

Pilatus set up an enormous booth at the Convention Center with a PC-12 that had been taxied over from KLAS in a caravan of airplanes driving on closed-off public roads at night. They also brought a mock-up of the PC-24 jet, whose certification is expected in 2017. The cabin volume is larger in the PC-24 compared to the PC-12 and this is most apparent in the spacious cockpit. Stretch out and relax! (as long as someone else is paying for the aircraft!)

What’s new for 2016 in the PC-12? The plane now ships with a 5-blade Hartzell composite prop, which reduces cabin noise by about 2 dB and improves performance slightly. The new prop, a flush main door handle, reconfigured antennae, and some gap seals result in a 5-knot improvement in cruise speed (to a claimed 285 knots). The prop is available as a retrofit for about $68,000 after trade-in of the old 4-blade prop.

Nearly all significant advances in airplanes have started with an improved engine. General Electric announced an “Advanced Turboprop” to be delivered in 2019 for a Cessna clean-sheet competitor to the PC-12. The new engine will offer a FADEC, perhaps 15 percent better fuel efficiency than the PT6 in the PC-12, a longer time-between-overhaul, and no hot section inspection at the midpoint.

Judging by the Maintenance and Operation seminar put on by Pratt & Whitney, the PT6 is performing pretty well for a dinosaur. With 51,000 engines built so far I expected the room to be packed but in fact it was nearly empty:

When all of the owners and operators are wandering the show floor instead of coming to the M&O seminar, you know that a product is bulletproof!

The presentation was by Craig Huisson, general manager of PT6A customer service. It was all business from the first slide: Here are the five things that you can do to make the next overhaul cheaper. The subsequent slides were mostly of the following form: “Here’s a part that failed. Here’s how we redesigned it. Here’s what you can do to check for a similar failure.” Huisson didn’t mention how great Pratt was, what the mission statement might be, or the inferiority of competitors. However, it was apparent from the slides that Pratt has tried to learn something from every failure, even ones that did not result in an engine shutdown. Huisson asked operators in the audience for ideas as to how Pratt could support them better. He took careful notes, promised publications in response, and handed out his business card for follow-up. If Pratt can add a FADEC to all of the low-power PT6 engines by 2019, GE is going to have a tough time competing!

[Practical tips: (1) The superstitious practice of running ITTs well below the top of the green arc, e.g., below 720 in the climb and below 700 in cruise, is actually helpful to the engine–temperature is the enemy; (2) do a lot of compressor washes (Pratt is hoping to make this easier so that an A&P mechanic is not required) to avoid corrosion; (3) borescope inspection every 200 hours, coinciding with the fuel nozzle cleaning. ]

The Pilatus Maintenance and Operations seminar was standing-room-only, despite only 1350 airframes having been produced. The structure was more or less the opposite of what Pratt had set up. We watched a video of the PC-24’s first flight. We learned the Pilatus mission statement, which takes up nearly a full page. We learned that Pilatus is better than other turboprop manufacturers and tries to do everything so much better that the company establishes a new category of aircraft: “Pilatus Class.” An example of this above-and-beyond approach was that the company recently made “pilot information manuals” (more or less what the pilots have up front) available on its web site. The presenter was seemingly unaware that Cirrus had managed to do this more than 10 years earlier or that, as noted in my review of the PC-12, unlike other manufacturers, Pilatus leaves pilots with manuals in which much safety-critical information, such as proper airspeeds to fly, is buried in a supplement in a separate binder (a consequence of changing the aircraft’s gross weight without following the industry-standard practice of revising the manual).

In later discussions with other PC-12 operators who’d been in the room, one said “They spent the whole meeting blowing smoke up our ass about how great Pilatus is. I didn’t learn anything about maintenance or operations.” One big challenge in maintaining the PC-12 is that anything involving electronics doesn’t seem to have been designed for maintenance. If a warning light comes on intermittently and a maintenance shop can’t duplicate the behavior in a hangar there is generally no information logged by the aircraft about the signals present at various locations that led up to the warning light. The mechanic is left to wonder “Is it a bad wire connection? Is it a bad board full of relays and logic?” This leads to a certain amount of hopeful board-swapping more or less at random. Board swaps tend to introduce additional problems because the Pilatus pool of spare boards contains many that were previously returned by customers as broken. A board that works fine during a bench test at Pilatus can be are stamped “good” and shipped out to a different customer. In a world where computers and memory are cheap there should be almost no situation in which an airplane can’t self-diagnose, e.g., “at 12:32:47Z there was a mismatch between information on Board A and information in the central warning system, therefore replace Wire A127” or “the signals on Board B should have resulted in Relay B4 closing but the output of that Relay indicates that it did not close, so replace Replay B4 and/or Board B.”

Practical good news from the meeting: The $15,000 pitch trim actuator that formerly needed to be replaced every 5 calendar years can now be run for 7 years as long as you don’t fly more than 3400 hours during those 7 years. The “ultimate life of the airframe is now up to 50,000 hours.” It costs about $100 per hour to go from 20,000 to 25,000 hours ($500,000 for the first phase of the extension program). If you actually have some reasonable prospect of burning through 50,000 hours the per-hour cost of the extension programs can fall to as low as $50.

What about quieting down the cabin? The folks at EAR, a subsidiary of 3M, say that sound-proofing materials are getting better every year and that they recently took 5 dB out of a Gulfstream cabin compared to the previous design with no increase in weight. It costs them between $50,000 and $100,000 to design a kit for an aircraft, so if there is enough interest from Pilatus operators we could see 4 dB of noise reduction within the cabin. Combined with the 5-blade prop that would make the PC-12 as quiet inside as some business jets, albeit still about 6 dB noisier than being inside a newer Airbus or Boeing. (See my PC-12 review for some measured dBA levels.)

What if you want a cabin filled with the noise of “Whoa, look how cool my avionics are”? The Garmin G600/GTN 650/750 option remains available at roughly $180,000, notably from J.A. Air. This is a simple-to-operate system for pilots accustomed to all things Garmin and leaves the EIS (engine and fuel) display as well as the King 325 autopilot. IS&S was at the show with a beautifully-painted-by-Hillaero PC-12 that had been modernized with three big screens and autothrottles. This should be certified by the spring of 2016 and cost about $300,000. The autothrottle system knows all of the torque and ITT limits, e.g., for hot-and-high takeoffs. It looks like a great system but it leaves the legacy AHARS systems in the airplane and each is $25,000 to exchange in the event of failure. IS&S replaces the EIS display but leaves the King 325 autopilot. It looks beautiful but weekend pilots accustomed to Garmin may find the interface challenging to learn. Honeywell showed its AeroVue system, currently announced for the King Air and some jets but a natural to put into the PC-12 due to the fact that a related system is factory equipment on the latest PC-12 NG airplanes. This system fits the Pilatus panel a lot better than the Garmin G600. The screens are bigger and there is less unused space. AeroVue includes a modern autopilot. It is unknown whether Honeywell will actually do this for the PC-12 and also unknown what Honeywell will charge for an annual avionics warranty. Finally, Sandel showed its crazy-clean and crazy-cheap Avilon flight deck for the King Air. The press release says “a guaranteed fly-away price of $175,000” and the salespeople talked about a 5-day install. This seems comparable to what Garmin has priced at $400,000 (a G1000 for the King Air) and a month of install time. It might be a very strong competitor if released for the PC-12.

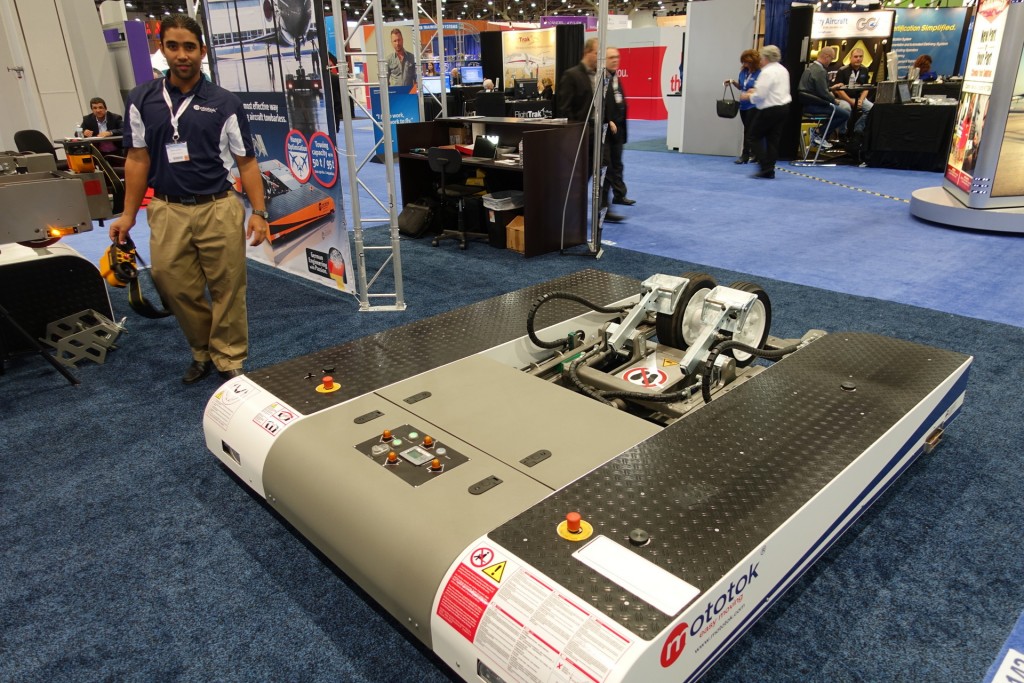

When the trip is over and you want to have the coolest conceivable tug to push the PC-12 back in the hangar?Mototok is the German solution suitable for an Al Gore-class private jet. If you’re rather spend $5,000 on a remote-controlled tug, the American equivalent for light aircraft that I saw at the show is AC Air Technology (fun videos, especially of the Robinson R44 helicopter).

It’s really amazing how apparently difficult it is to build a light jet 70+ years into the jet age. I can understand why undercapitalized players like Adam and Diamond would fail (BTW, who in their right mind would give a small aircraft maker any capital given the industry track record?) but even Honda has had problems getting their program to the point where they could actually sell the planes to customers. Is this mainly the FAA’s fault (would not surprise me) or are there other factors?

Izzie: I don’t think that it is fair to blame the FAA because companies that get certification through the Swiss, Brazilian, or Austrian authorities end up on similar timelines (within 30 percent anyway). Bureaucracy and regulation are definitely a part of the reason for the long timelines, especially since oftentimes the regulations are a moving target. Honda said that one reason for their delay is that the FAA changed the requirements for pressurization systems above FL410 in the middle of their project (the HondaJet can climb to FL430, or roughly 43,000′ above sea level).

Phil,

I occasionally enjoy watching the various planes shown on Flightradar24.com and late at night the one prop-powered plane that seems very prevalent is the Pilatus. Is this aircraft a popular choice for night or IFR flights or am I simply looking at an area (mid-Atlantic U.S.) that coincidentally has a bunch of these planes?

“The PC-12 has some unique capabilities, however, such as being able to operate from short, dirt, and/or grass runways,…”

I did once come across a PC-12 at a grass airstrip in rural Quebec where it look very royal among the beat up Cessna 172’s and such, but how big a consideration is this capability in the US? What % of Pilatus flights are actually made from unimproved or short runways? Or is this like all-wheel drive in cars – something that buyers perceive as nice to have even if they rarely need it?

Exactomatic: Why so many PC-12s for night/IFR flights compared to other propeller-driven planes? New Hampshire-based PlaneSense is a big operator with more than 30 PC-12s each of which flies close to 1000 hours per year in a primarily east-of-the-Mississippi service area. There are a lot more Cessna 172s out there, of course, but they aren’t commercially operated and might fly closer to 100 hours per year each. A professionally piloted PC-12 is a lot more likely to be in weather or in the dark than a weekend pilot’s little Cessna or Cirrus.

Izzie: The grass runway capability is useful in Europe where there are high fees at paved airports. In the U.S. the short runway capability is frequently used by commercial operators. If you have a house on Block Island, RI, for example, you won’t be getting there in a turbojet, but the paved 2500′ runway is ample for a Pilatus.