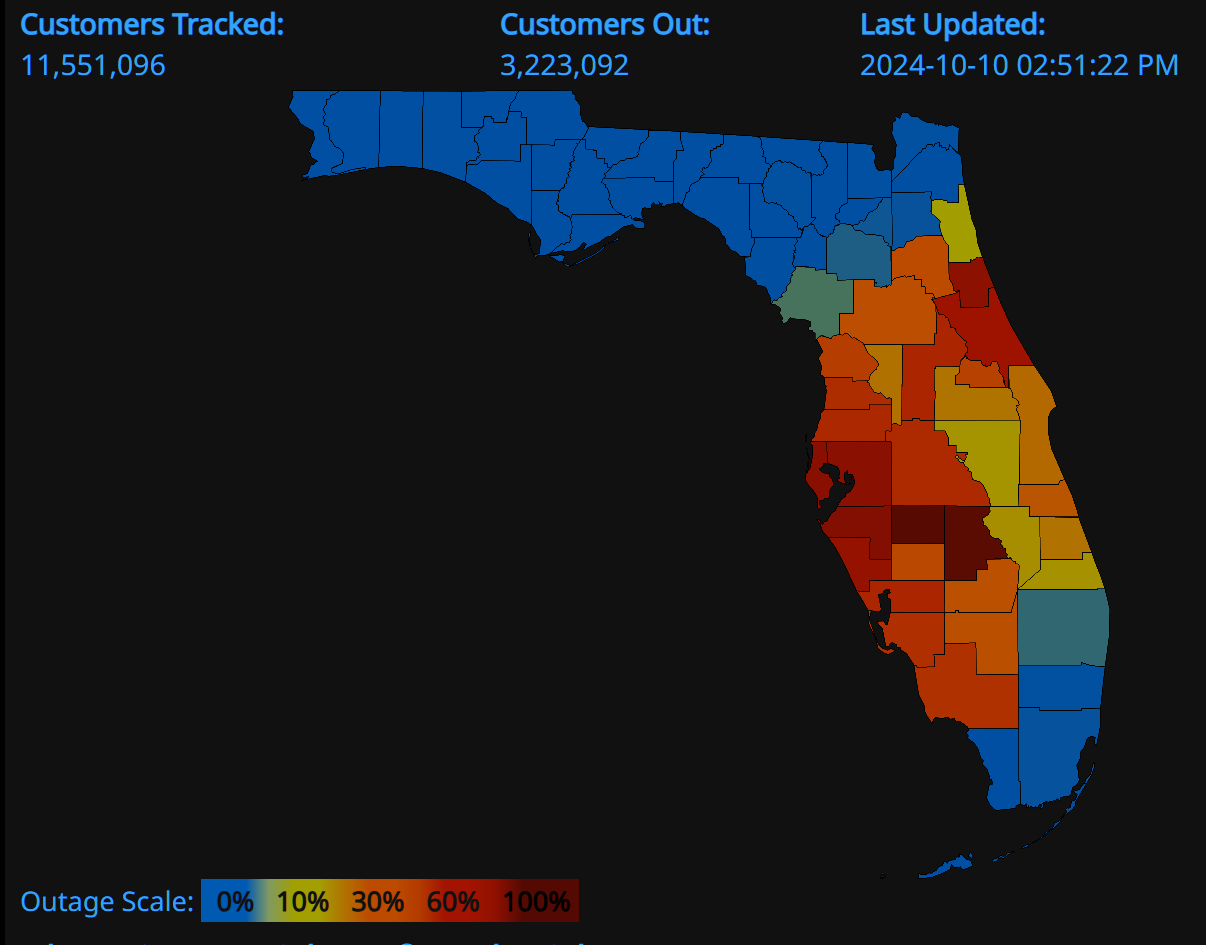

Landfall: October 9, 2024 at 8:30 pm. Supposedly about 4 million customers lost power (source: Ron DeSantis press conference).

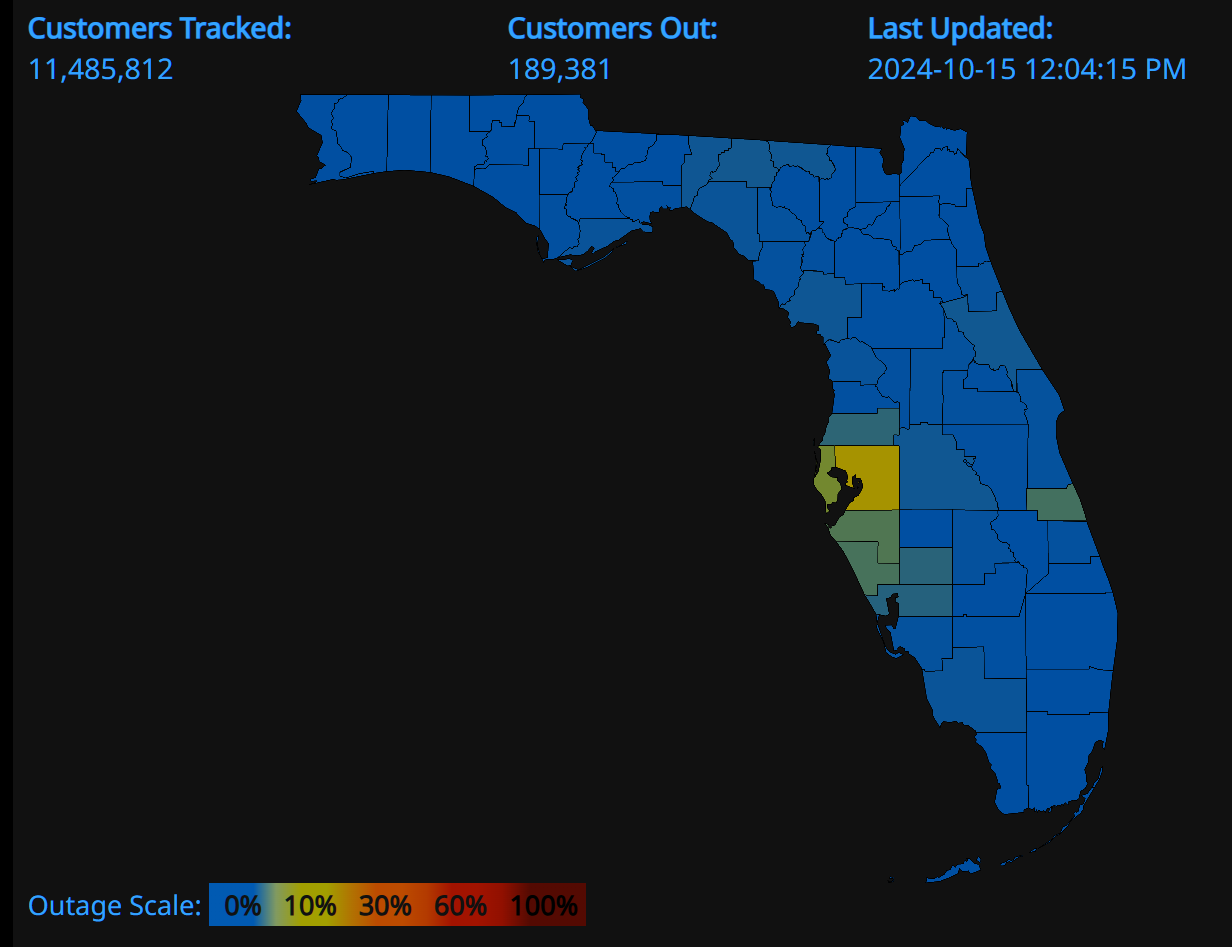

Mid-afternoon the next day:

Early evening:

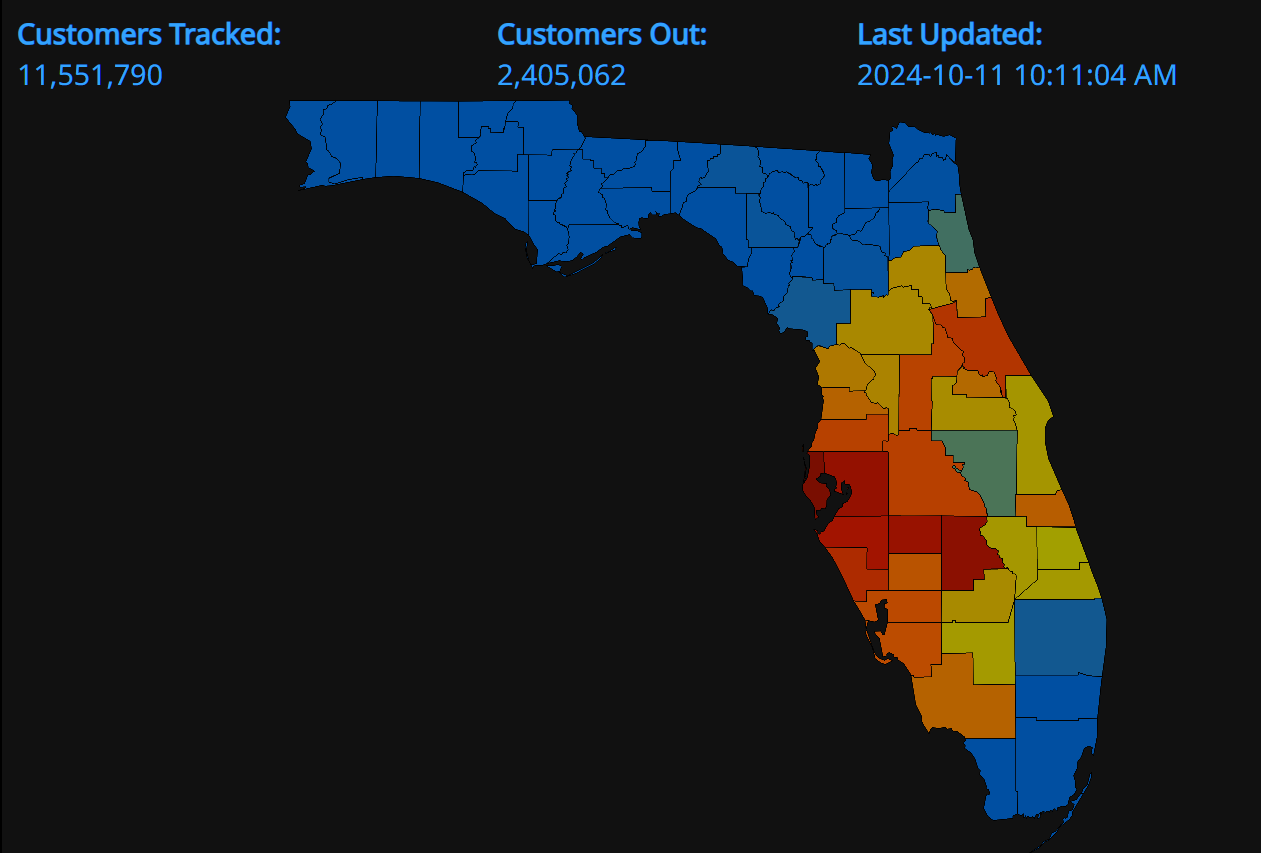

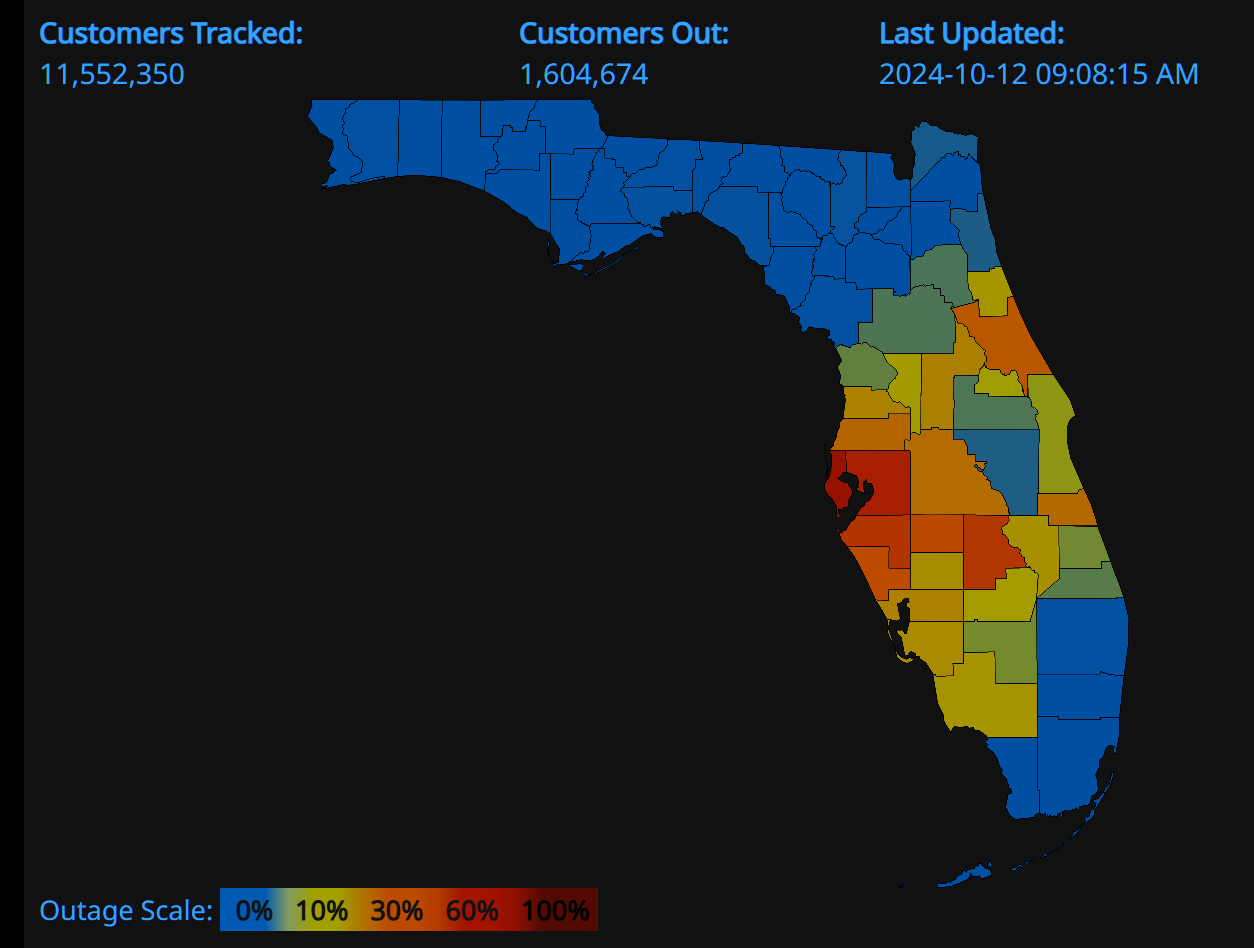

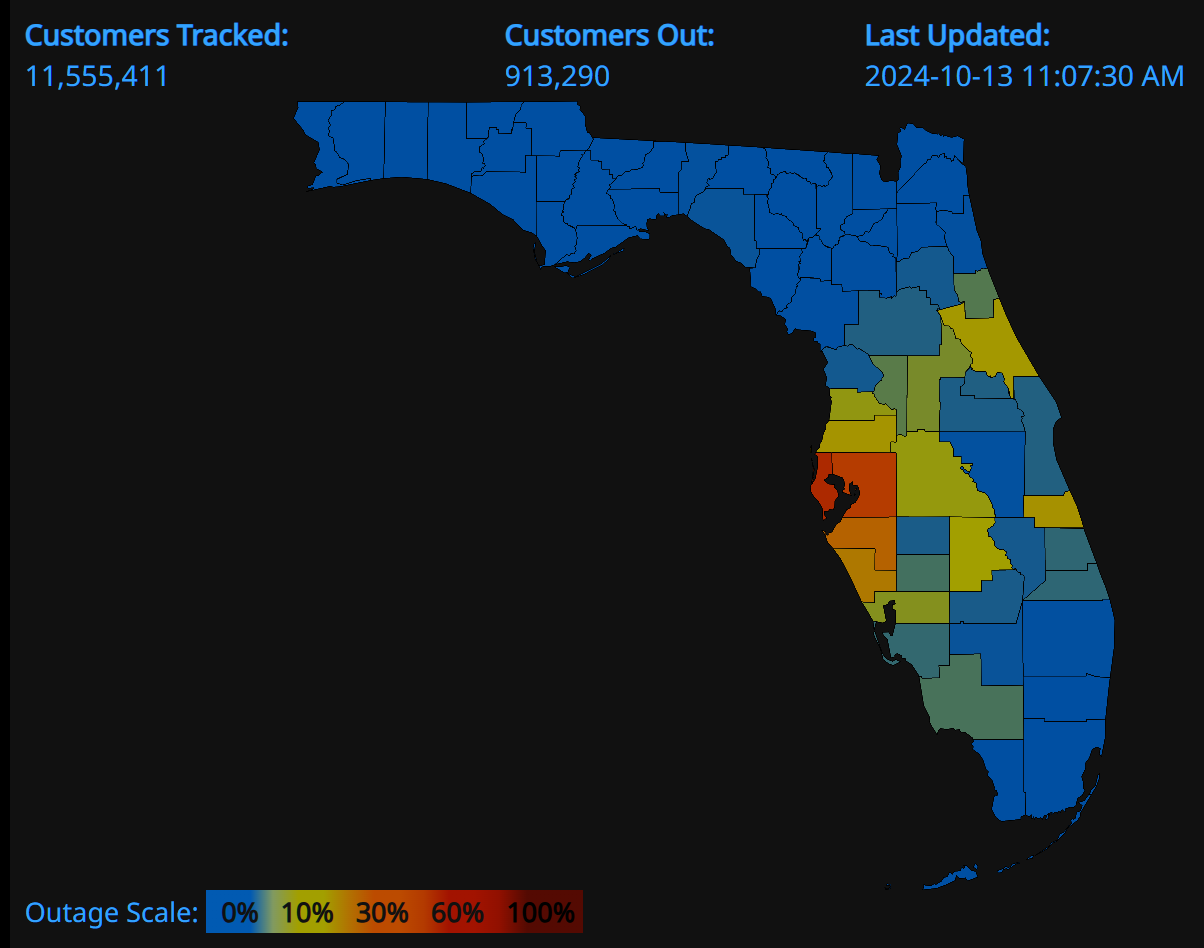

The morning of the second day:

Apparently there was power at the big airport in Tampa because they resumed operations about 36 hours after the hurricane made landfall:

(Orlando had reopened a few hours earlier, so they too had power despite being in the middle of the Band of Destruction (TM).)

Afternoon of second day:

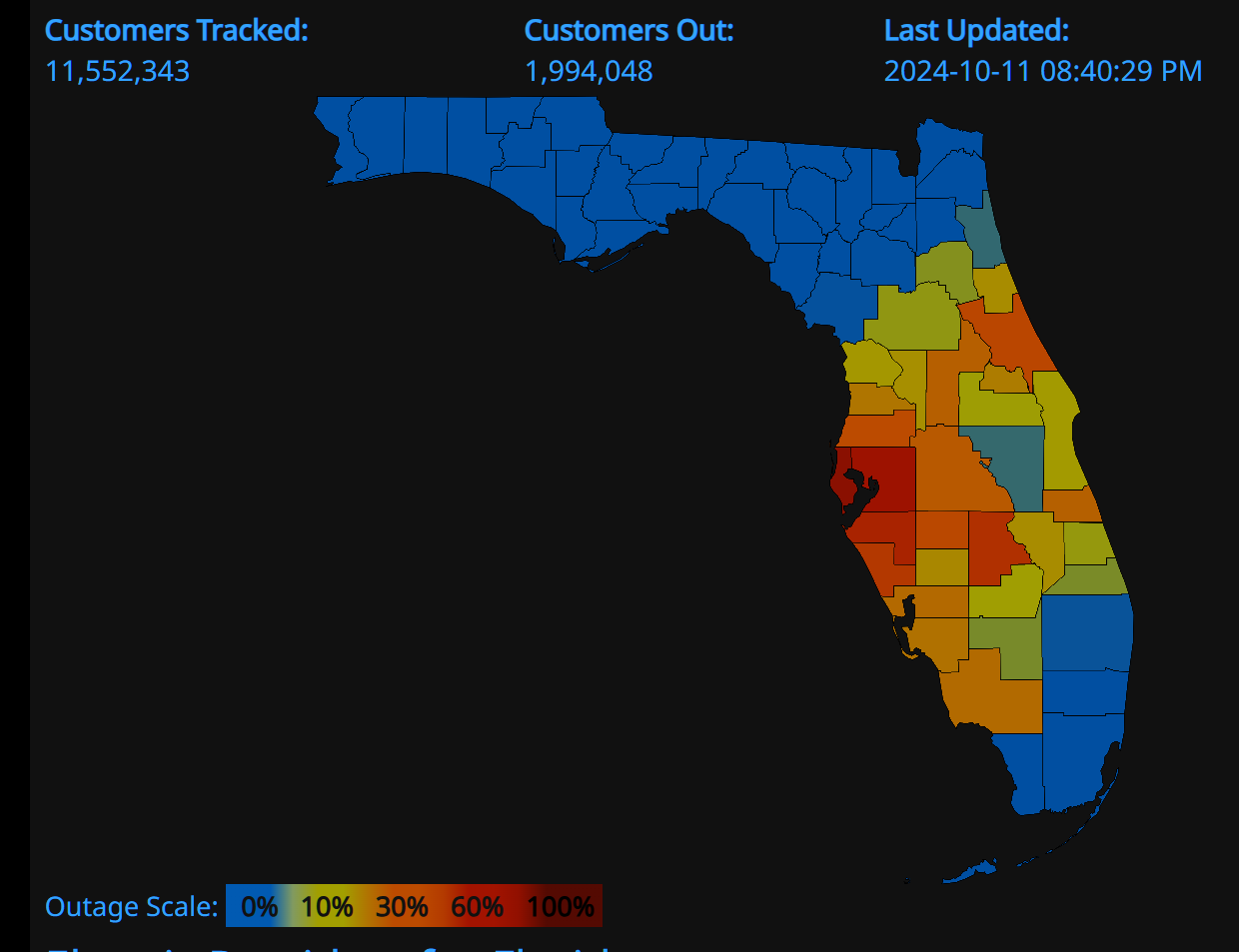

About 48 hours after the hurricane hit, the total customers out has declined from 3.4 million to 2 million:

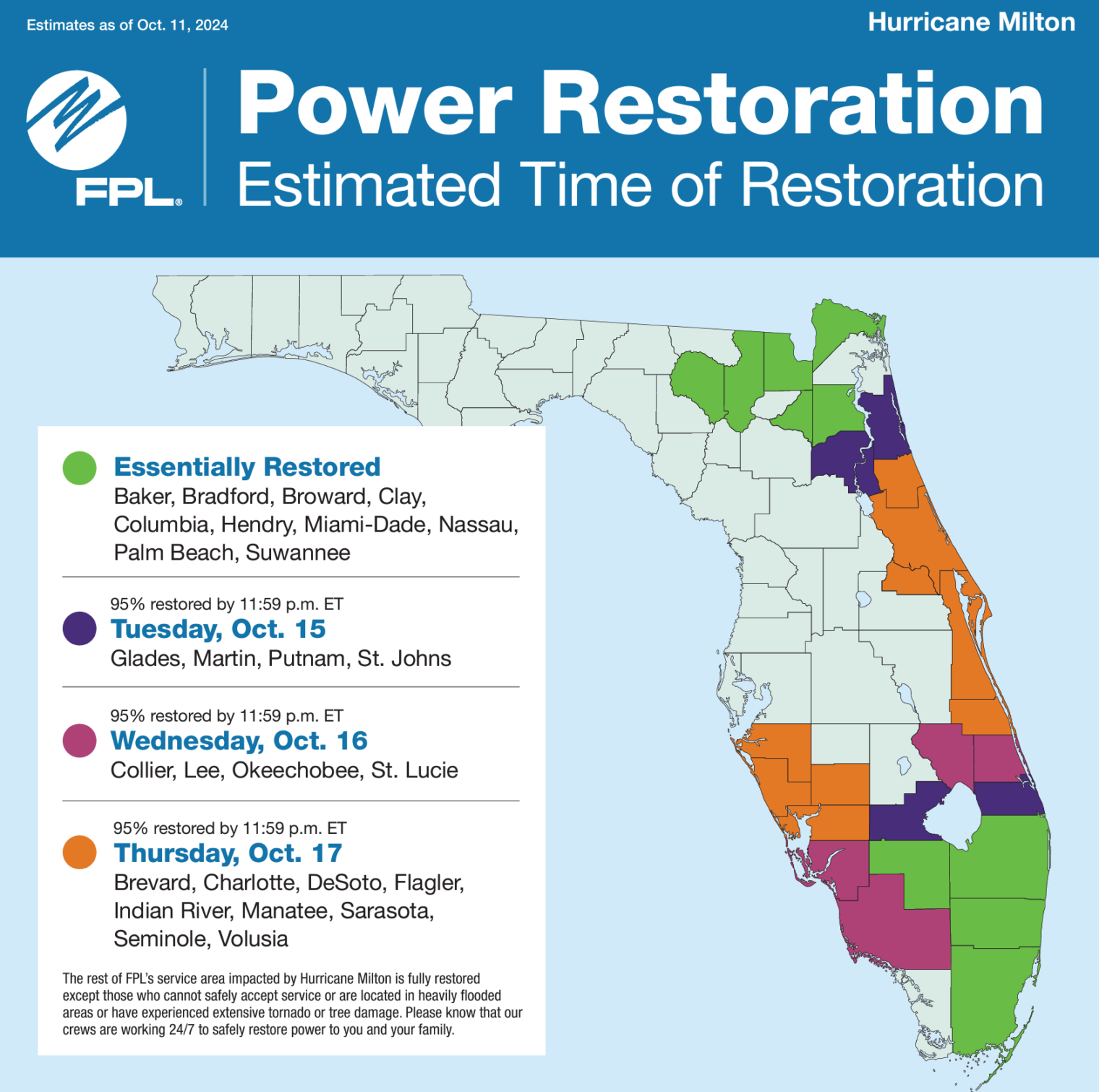

The bad news is that restoration for some Floridians won’t be until 8 days after the hurricane made landfall. Here’s FPL’s estimate:

I’m not sure if people in neighborhoods with underground lines (like ours!) will get power sooner. Currently, 10 percent of FPL’s customers are out versus 17 percent for the state.

I can’t figure out why the customer numbers are so high. I thought that the transmission lines were designed to handle hurricane-force winds (and they were further beefed up after 2019; see Tough questions from reporters for Ron DeSantis). Maybe there are a lot of neighborhoods with above-ground powerlines for local distribution?

Strong independent female linewomen continued to work through the night, apparently…

2.5 days after landfall, it looks like Naples and Fort Myers are on their way back to normal while half of Tampa is dark. More than half of the Floridians who originally lost power now have it back (thanks once again to the efforts of linewomen who identify as female):

around lunch time…

Three days (72 hours) after landfall:

The pace of restoration seems to slowed down in the dark:

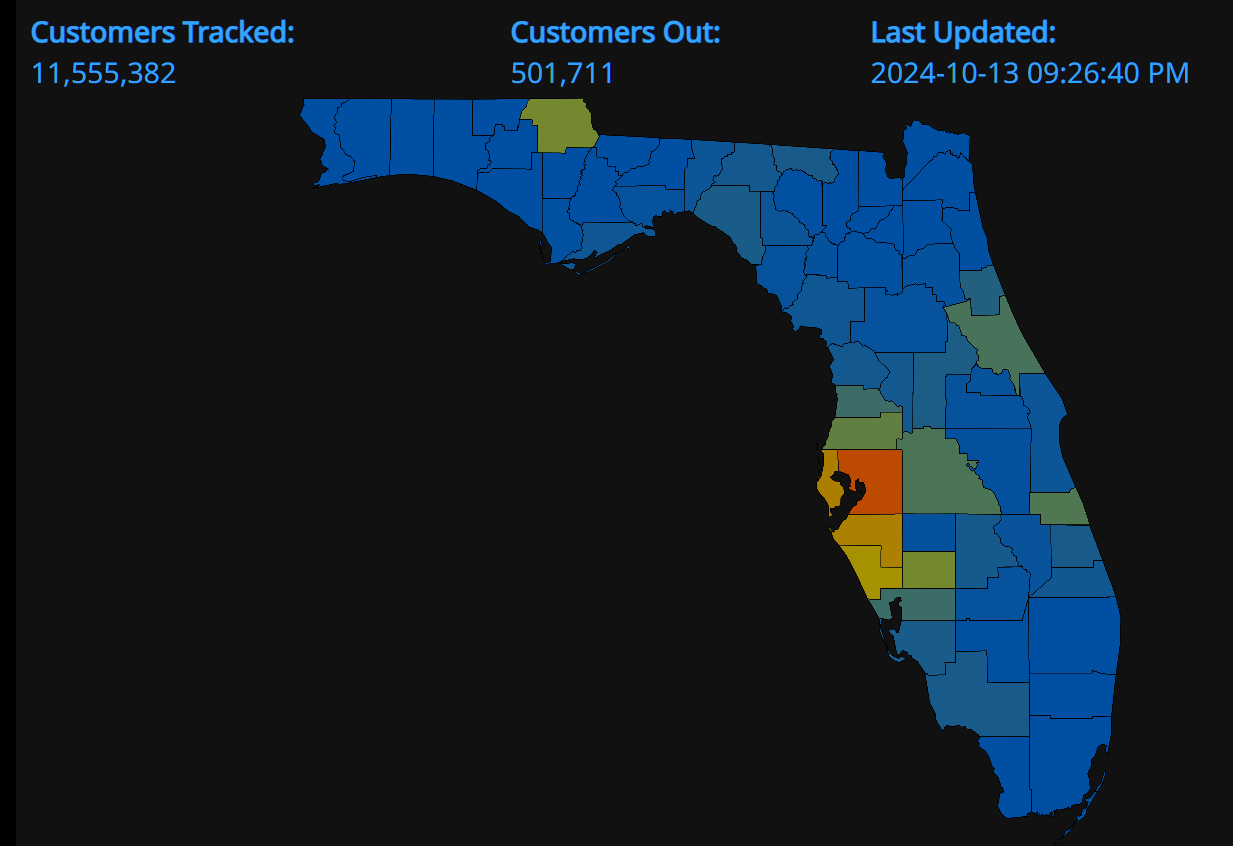

3.5 days after landfall:

Not a great situation in Tampa, with more than one third of customers without power. On the other hand, the total is down below 1 million compared to 4 million at the start.

Four days (96 hours) after landfall and about 500,000 customers are still out. More than 235,000 of them are Tampa Electric customers, which has only 840,000 total customers.

Florida Power and Light now says that they’ll have nearly everyone restored, even in directly hit Sarasota, by Tuesday night. (Also that they’ve thus far restored 90 percent of their affected customers, 1.8 million people who’d lost power at one point.) Speaking of FPL, if you were to watch their X feed you’d learn that electricity restoration is definitely not something that white males do:

And as of Tuesday at noon, FPL indeed had all but 38,000 customers back online. Tampa Electric (TECO) continued to be an outlier with 100,000 customers still dark.

Full post, including comments