A fourth post based on The Women Who Flew for Hitler, a book about Hanna Reitsch and Melitta von Stauffenberg.

Although both of these women were awarded Iron Crosses by Adolf Hitler, only Hanna was an enthusiastic supporter of National Socialism. The aeronautical engineer and disciplined test pilot Melitta survived until just three weeks before the end of the war so we’ll never know what she would have accomplished in the world of civilian aviation. Much of her work was on instruments and systems for flying at night and in bad weather, so she likely would have done valuable work in the Jet Age.

During the war, Hanna had lost her nerve only once. This was during a morale-boosting visit to the Russian Front:

No sooner had she reached the first German ack-ack position than the Russians started a heavy bombardment. ‘Automatically everyone vanished into the ground, while all around us the air whistled and shuddered and crashed,’ she wrote. After their own guns had pounded out their reply, a formation of enemy planes began to bomb the Wehrmacht position. ‘I felt, in my terror, as though I wanted to creep right in on myself,’ Hanna continued. ‘When finally to this inferno were added the most horrible sounds of all, the yells of the wounded, I felt certain that not one of us would emerge alive. Cowering in a hole in the ground, it was in vain that I tried to stop the persistent knocking of my knees.’

(The above suggests that Israel could have brought the Gaza fighting to a swift conclusion if it had used 155mm artillery to attack Hamas-held positions rather than high-tech drones and other precision munitions that have convinced Palestinians that war with the IDF is a manageable lifestyle (in a June 2024 poll, the majority of Palestinians wanted to continue fighting against Israel (Reuters)). The initial death toll among civilians would have been higher, but the long-term death toll might have been lower if the IDF fought intensively enough to motivate Gazans to surrender, release their hostages, and rat out Hamas members.)

Hanna had friends with direct knowledge of the German death camp system and had seen photographs, taken by Russians, of the Majdanek extermination camp (captured in July 1944). The reports and the photos, however, did not change her views regarding the overall merits of the Nazi system. Regarding the concentration camps, the book covers another “breaking the glass ceiling” angle:

Buchenwald covered an immense site, but its hundreds of barracks were overflowing with thousands of starving prisoners. The camp was ‘indescribably filthy’, one Stauffenberg cousin noted, and ‘there was always an air of abject misery and cruelty’. Female SS guards carried sticks and whips with which they frequently beat prisoners, especially if orders – given solely in German – were not obeyed immediately.

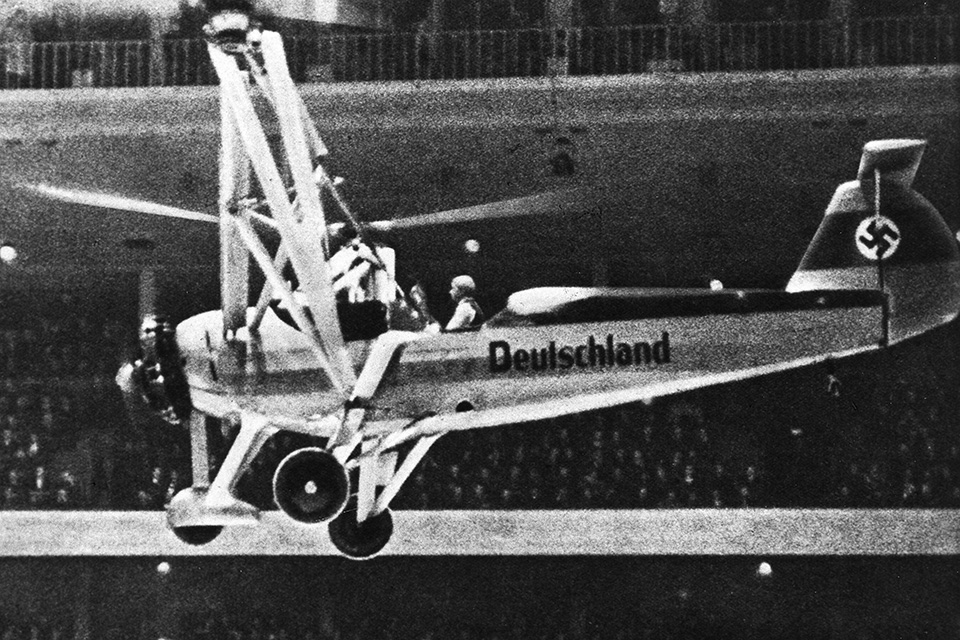

While the concentration and extermination camps were being overrun, Hanna was one of the last Germans to spend time with Hitler, flying into Berlin in April 1945 and landing a Fieseler Storch right next to the bunker.

In that instant Hanna decided that, if Greim stayed, she would also ask Hitler for the ultimate privilege of remaining with him. Some accounts even have her grasping Hitler’s hands and begging to be allowed to stay so that her sacrifice might help redeem the honour of the Luftwaffe, tarnished by Göring’s betrayal, and even ‘guarantee’ the honour of her country in the eyes of the world.49 But Hanna may have been motivated by more than blind honour. She had worked hard to support the Nazi regime through propaganda as well as her test work for the Luftwaffe, and there is no doubt that both she and Greim identified with Hitler’s anti-Semitic world view and supported his aggressive, expansionist policies. Hanna ‘adored Hitler unconditionally, without reservations’, Traudl Junge, one of the female secretaries in the bunker, later wrote. ‘She sparkled with her fanatical, obsessive readiness to die for the Führer and his ideals.’

In another example of how the Israelis might have defeated Hamas, the author notes that even a German-built underground bunker isn’t a practical refuge against sustained shelling.

Over the next few days, the Soviet army pushed through Berlin until they were within artillery range of the Chancellery. Hanna spent much of her time in Greim’s sickroom. Sometimes she dozed on the stretcher that had carried him in, but essentially she was a full-time nurse, washing and disinfecting his wound every hour, and shifting his weight to help reduce the pain. Any sustained sleep was now impossible as the bunker shook, lights flickered and even on the lower floor, fifty feet below ground, mortar fell from the eighteen-inch-thick walls.

Hanna escaped at the end of April 1945, flying as a passenger with Robert Ritter von Greim and his personal pilot. Hanna was captured by the Allies and interrogated by Eric Brown, a British pilot, and Americans interested in Germany’s advanced weapons.

‘Although she was reluctant to admit this,’ [Eric Brown] later wrote, it soon became evident that Hanna had never flown the plane under power, but only ‘to make production test flights from towed glides’.

To Eric it was clear that Hanna’s ‘devotion for Hitler was total devotion’. ‘He represented the Germany that I love,’ she told him. Hanna also denied the Holocaust. When Eric told her that he had been at the liberation of Belsen, and had seen the starving inmates and piles of the dead for himself, ‘she pooh-poohed all this. She didn’t believe it … She didn’t want to believe any of it.’ Such denial was painful for them both, but Eric found that ‘nothing could convince her that the Holocaust took place’. Hanna was, he concluded, a ‘fanatical aviator, fervent German nationalist and ardent Nazi’. Above all, he later wrote, ‘the fanaticism she displayed in her attitude to Hitler, made my blood run cold’.

When the Americans organized a press conference for her to publicly repeat her denunciation of Hitler’s military and strategic leadership, she instead defiantly asserted that she had willingly supported him, and claimed she would do the same again.

The only woman among the leaders awaiting trial, she was soon particularly close to Lutz Schwerin von Krosigk, the regime’s former finance minister. Having enjoyed long conversations ‘about everything’, she told him she could ‘feel your thoughts steadily in me, stronger than any words’. When she learnt that her brother Kurt had survived the war, she proudly wrote to him that for many months she had been ‘sitting behind barbed wire, surrounded by the most worthy German men, leaders in so many fields. The enemy have no idea what riches they are giving me.’

The Americans seemed unsure how to classify Hanna. In December 1945 they had recorded that she was ‘not an ardent Nazi, nor even a Party member’. Other memos listed her optimistically as a potential goodwill ambassador or even ‘possible espionage worker’. Hanna’s celebrity, and close connections with former Luftwaffe staff and others once high up in Nazi circles, made her a potentially valuable asset ‘with the power to influence thousands’. But her stated desire to promote ‘the truth’ was never translated into action. Eventually they decided to keep her under surveillance in an intelligence operation code-named ‘Skylark’. The hope was that she might inadvertently lead them to former members of the Luftwaffe still wanted for trial. Hanna started receiving her ‘highly nationalistic and idealistic’ friends as soon as she was released. To pre-empt criticism, she cast herself as a victim. She ‘had a worse time [in US captivity] than the people in concentration camps!’ the pilot Rudi Storck wrote in a letter that was intercepted.

Hanna knew about this surveillance and even asked US intelligence to give her a new car when her Fiat sports car broke down (we did give her the car!). It’s a little unfair to blame Hanna for thinking that the main thing that the Nazis did wrong was to lose the war:

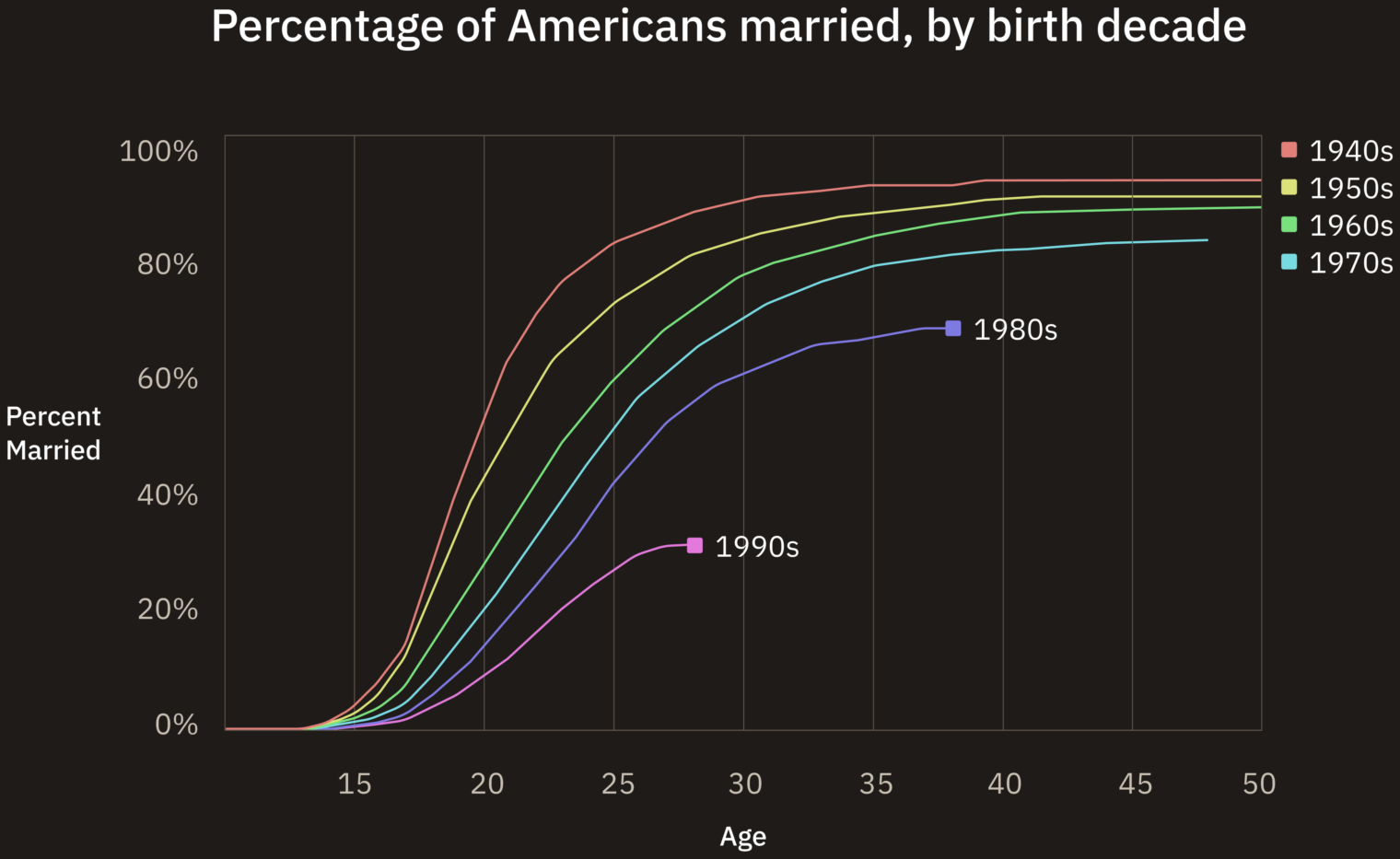

Among the national surveys that followed in West Germany, one from 1951 found that only 5 per cent of respondents admitted any feeling of guilt concerning the Jews, and only one in three was positive about the assassination plot.

How effective are trained psychologists?

Although acquitted in 1947, [SS officer] Skorzeny had been kept at Darmstadt internment camp to go through what he called ‘the denazification mill’.52 Hanna had been the first person he visited while on parole. Skorzeny escaped the following summer, eventually arriving in Madrid where he founded a Spanish neo-Nazi group.

Hanna’s two-month visit to India in 1959:

She loved the warmth of her reception, gave frequent talks on the spiritual experience of silent flight, and developed proposals for glider training with the Indian air force. She was also thrilled with what she called ‘the lively interest in Hitler and his achievements’ that she claimed to receive ‘all over India’.68 The cherry on the cake came when the ‘wise Indian Prime Minister’, Jawaharlal Nehru, requested she take him soaring. Hanna and Nehru stayed airborne for over two hours, Nehru at times taking the controls. It was a huge PR coup, widely reported across the Indian press. The next morning Hanna received an invitation to lunch with Nehru and his daughter, Indira Gandhi.

She was also warmly received in the U.S.:

In 1961 Hanna returned to the USA at the suggestion of her old friend, the aerospace engineer Wernher von Braun, who was now working at NASA. She often claimed to have refused post-war work with the American aeronautics programme on the basis that it would have been the ultimate betrayal of her country.† Braun felt differently, and occasionally tried to persuade Hanna to change her mind. ‘We live in times of worldwide problems,’ he had written to her in 1947. ‘If one does not wish to remain on the outside, looking in, one has to take a stand – even if sentimental reasons may stand in the way of coming clean. Do give it some thought!’

While in the States, Hanna also took the opportunity to join glider pilots soaring over the Sierra Nevada, and to meet the ‘Whirly Girls’, an international association of female helicopter pilots. As the first woman to fly such a machine, she found she had the honour of being ‘Whirly Girl Number One’. It was with the Whirly Girls that Hanna was invited to the White House, meeting President Kennedy in the Oval Office. A group photo on the lawn shows her in an enveloping cream coat with matching hat and clutch, standing slightly in front of her taller peers. Her smile is once again dazzling; she felt validated. In interviews she revealed that Kennedy had told her she was a ‘paradigm’, and should ‘never give up on bringing flying closer to people’.

She came back to the U.S. in the 1970s:

She tactfully did not attend the 1972 Munich Olympic Games, and does not seem to have commented on the murder of the eleven Israeli athletes. The highlight of that year for her was a return to America, where she was honoured in Arizona, and installed as the first female member of the prestigious international Society of Experimental Test Pilots. She could hardly have been happier, sitting in a hall of 2,000 people, discussing a possible new ‘Hanna Reitsch Cup’ with Baron Hilton. Back in Germany, she was now receiving hundreds of letters and parcels from schoolchildren as well as veterans, and even became an ambassador for the German section of Amnesty International. ‘There are millions in Germany who love me,’ she claimed, before adding, ‘it is only the German press which has been told to hate me. It is propaganda helped by the government … They are afraid I might say something good about Adolf Hitler. But why not?’

What’s Amnesty International up to lately? Since October 7, 2023, at least, tweeting out a continuous stream of support for one side in the Gaza fighting. Example:

Full post, including comments