Folks are upset that Trump and DOGE may shut down USAID and cut U.S. foreign aid spending (state-sponsored NPR). This is consistent with a classic 2005 interview “For God’s Sake, Please Stop the Aid!”. Quotes below, but not in quote style for improved readability (my highlights in bold).

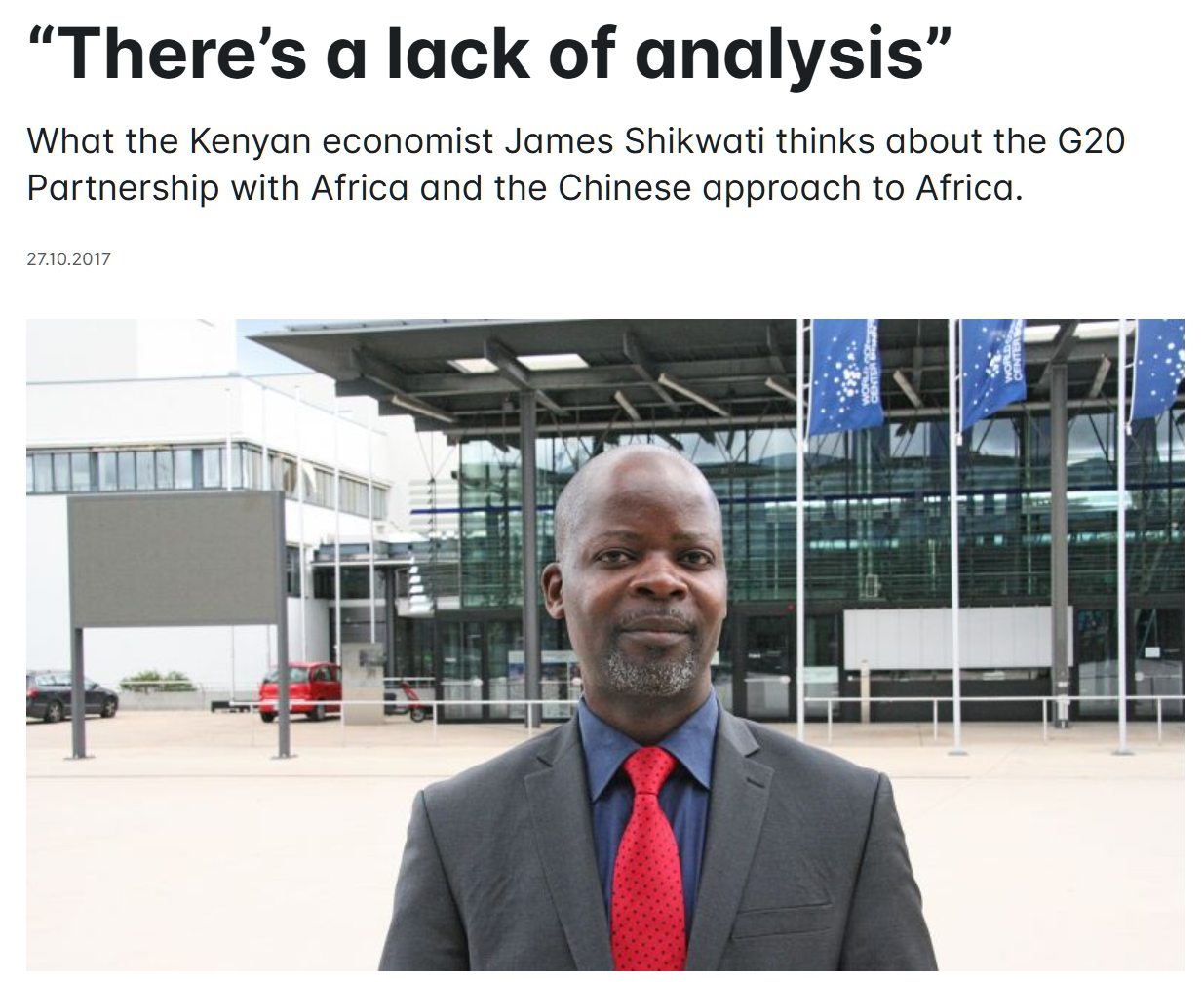

The Kenyan economics expert James Shikwati, 35, says that aid to Africa does more harm than good. The avid proponent of globalization spoke with SPIEGEL about the disastrous effects of Western development policy in Africa, corrupt rulers, and the tendency to overstate the AIDS problem.

SPIEGEL: Stop? The industrialized nations of the West want to eliminate hunger and poverty.

Shikwati: Such intentions have been damaging our continent for the past 40 years. If the industrial nations really want to help the Africans, they should finally terminate this awful aid. The countries that have collected the most development aid are also the ones that are in the worst shape. Despite the billions that have poured in to Africa, the continent remains poor.

SPIEGEL: Do you have an explanation for this paradox?

Shikwati: Huge bureaucracies are financed (with the aid money), corruption and complacency are promoted, Africans are taught to be beggars and not to be independent. In addition, development aid weakens the local markets everywhere and dampens the spirit of entrepreneurship that we so desperately need. As absurd as it may sound: Development aid is one of the reasons for Africa’s problems. If the West were to cancel these payments, normal Africans wouldn’t even notice. Only the functionaries would be hard hit. Which is why they maintain that the world would stop turning without this development aid.

SPIEGEL: … corn that predominantly comes from highly-subsidized European and American farmers …

Shikwati: … and at some point, this corn ends up in the harbor of Mombasa. A portion of the corn often goes directly into the hands of unsrupulous politicians who then pass it on to their own tribe to boost their next election campaign. Another portion of the shipment ends up on the black market where the corn is dumped at extremely low prices. Local farmers may as well put down their hoes right away; no one can compete with the UN’s World Food Program. And because the farmers go under in the face of this pressure, Kenya would have no reserves to draw on if there actually were a famine next year. It’s a simple but fatal cycle.

SPIEGEL: Would Africa actually be able to solve these problems on its own?

Shikwati: Of course. Hunger should not be a problem in most of the countries south of the Sahara. In addition, there are vast natural resources: oil, gold, diamonds. Africa is always only portrayed as a continent of suffering, but most figures are vastly exaggerated. In the industrial nations, there’s a sense that Africa would go under without development aid. But believe me, Africa existed before you Europeans came along. And we didn’t do all that poorly either.

SPIEGEL: But AIDS didn’t exist at that time.

Shikwati: If one were to believe all the horrorifying reports, then all Kenyans should actually be dead by now. But now, tests are being carried out everywhere, and it turns out that the figures were vastly exaggerated. It’s not three million Kenyans that are infected. All of the sudden, it’s only about one million. Malaria is just as much of a problem, but people rarely talk about that.

SPIEGEL: And why’s that?

Shikwati: AIDS is big business, maybe Africa’s biggest business. There’s nothing else that can generate as much aid money as shocking figures on AIDS. AIDS is a political disease here, and we should be very skeptical.

Shikwati: Why do we get these mountains of clothes? No one is freezing here. Instead, our tailors lose their livlihoods. They’re in the same position as our farmers. No one in the low-wage world of Africa can be cost-efficient enough to keep pace with donated products. In 1997, 137,000 workers were employed in Nigeria’s textile industry. By 2003, the figure had dropped to 57,000. The results are the same in all other areas where overwhelming helpfulness and fragile African markets collide.

Shikwati: … jobs that were created artificially in the first place and that distort reality. Jobs with foreign aid organizations are, of course, quite popular, and they can be very selective in choosing the best people. When an aid organization needs a driver, dozens apply for the job. And because it’s unacceptable that the aid worker’s chauffeur only speaks his own tribal language, an applicant is needed who also speaks English fluently — and, ideally, one who is also well mannered. So you end up with some African biochemist driving an aid worker around, distributing European food, and forcing local farmers out of their jobs. That’s just crazy!

A 2017 look at the interviewee:

Full post, including comments