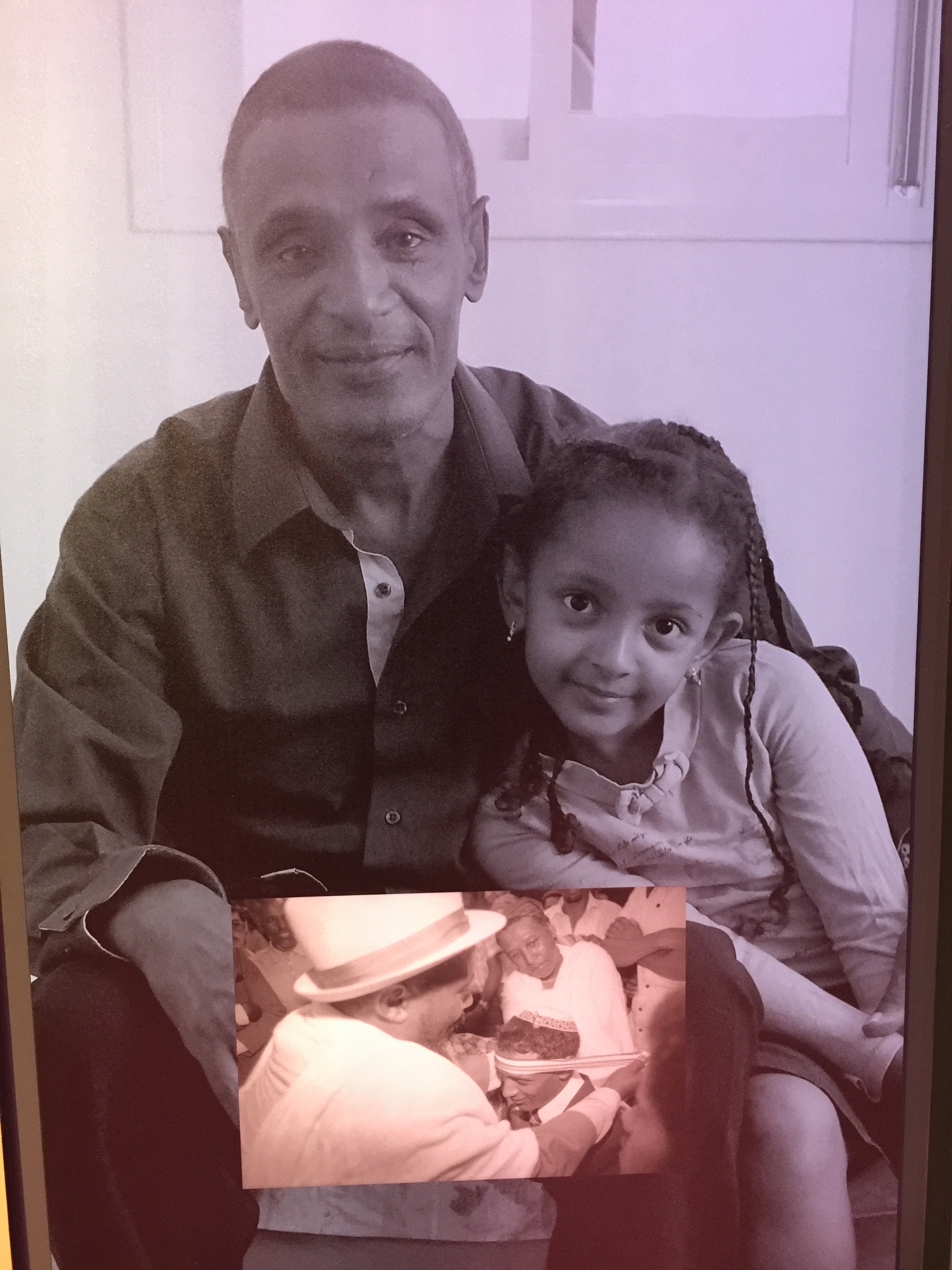

Israel is a country of immigrants, which means that many Israelis make the decision to marry in a different legal system from that in which they will get divorced (the fate of 30-41 percent of Israeli married couples, depending on who is counting). At the Museum of the Diaspora, for example, an exhibit shows a guy who was married in Ethiopia and then divorced in Israel:

Based on my discussions with some experienced attorneys, Israeli divorce lawsuit defendants from countries that operate under Civil Law will probably be the ones who wish that they had stayed in their original home. Jewish law provides few financial incentives for divorce plaintiffs. If a man divorces a woman he has to pay her according to the ketubah, essentially a prenuptial agreement. If a woman divorces a man she may not receive any share of the man’s future income (it could still be financially rational for a woman to divorce her husband if she can find someone richer to replace him with). On top of this ancient legal tradition Israel has layered some aspects of British common law. The result of this combination is that what would have been a straightforward procedure in Europe or Russia (examples) with legal fees (if any) limited to a small percentage of total assets can turn into an American-style no-holds-barred war in Israel.

The end of an Israeli marriage results in the parties’ assets being consumed by lawyers in both the government-run courts (about 74,000 cases in 2015) and also in a religious court. A woman who wants to be rid of her husband will sue him in the government court for property division, custody, and child support. The divorce per se is litigated in a religious court, e.g., the rabbinical court for Jews, an Islamic court for Muslims. “The rabbinical court is a lot more efficient than the civil court,” said one lawyer, “but it can still cost [$50,000+] in fees to a separate attorney.”

Israeli plaintiffs who follow economic incentives will sue a husband for property division, custody, and child support in the civil court but not seek a divorce in the rabbinical court. The litigation posture is that she wants to stay married and isn’t interested in a divorce, but she wants to live separately, be the primary parent, and get paid for taking care of the children. Then there is a game of chicken to see who will crack and sue first in the rabbinical court (as noted above, if the woman were to initiative a divorce per se she wouldn’t be entitled to alimony).

Property division is simple in theory but complex and expensive to litigate in practice. It is supposedly a California-style system in which premarital property cannot be obtained by a plaintiff, but property acquired during the marriage is divided 50/50. “There was a Supreme Court decision about two months ago,” said one source, “in which a man had inherited an apartment that was rented out. He deposited the rent into a joint account and that was enough to make the property divisible by the court.” Plaintiffs also may allege that a defendant has hidden assets and don’t need any documentary evidence to keep the allegation alive through a final trial. If there are assets worth fighting over, litigation can take more than three years. “If there are 1 million shekels in assets [$250,000] the fees will end up being about 1 million shekels,” said the attorney. As in the U.S., a judge can order a defendant to pay a plaintiff’s legal costs but this may be only 20 percent of the “real costs.”

What happens to the joint apartment (standalone houses are rare in Israel) during the three years of litigation? “The court cannot order the husband out,” said the attorney, “unless the wife makes an allegation of domestic violence, so either the couple negotiates or, more commonly, the wife accuses him of physical or psychological abuse.” (A variety of U.S. states have a similar system; see “The Domestic Violence Parallel Track” and Amber Heard)

Israel is not a great jurisdiction for profiting from extramarital sex. Unlike many U.S. states where it is more profitable to have sex with a high-income person than to be in a long-term marriage with a middle-income person (some numbers), in Israel child support starts by considering the needs of the child. This in contrast to the U.S. system in which the primary factor determining profitability is the income of the target of the child support lawsuit (see the History chapter for how the big switch happened around 1990). Child support can still be profitable in Israel if there was a marriage and a shared household for at least a year or two. Now the defendant can be ordered to pay to keep the children in the lifestyle to which they were accustomed during the marriage and the only way to enable that is also to keep the plaintiff in the lifestyle to which she was accustomed. If the litigants just met for one night in a bar, however, the official standard for child support is more based on the cost of rearing a typical Israeli child.

As noted in a July 23 posting, custody lawsuits are simple if the child(ren) are under 6: Mom wins. Mom also is guaranteed to be the one receiving child support, even if the children live with their father. As in the U.S., legal fees can be expended to determine a child’s schedule but the end result is nearly always that children are entitled to spend every other weekend with the father (Friday morning until Saturday evening or Sunday morning) plus a few hours on a weekday. With older children, 50/50 schedules are possible though the cash continues to flow from father to mother even when the two parents have equal incomes or when the mother earns more than the father. The mother’s revenue is reduced to one third at age 18 when a child will enter the military and cut off at age 21 (compare to full cashflow through 21 in New York or 23 in Massachusetts).