“Florida Coastal Living Reshaped by Hurricane Housing Codes” (Wall Street Journal, October 17, 2022) opens with what I think is the usual misleading footage of a destroyed section of Fort Myers Beach, i.e., of a trailer park that was predictably no match for a hurricane. The article contains, however, some interesting stuff about what is entailed in building a house that can survive on barrier islands:

Five blocks away [from a destroyed wooden 1976 “cottage”] stands a roughly $2 million house that weathered the storm with negligible damage. Fernando Gonzalez built the two-story, concrete-block home six years ago to exceed the requirements of the building code at the time.

Instead of raising the house 12 feet as required, he said he lifted it 4 feet more. He said he also built the foundation stronger than mandated, going 6 feet below the ground and installing thick concrete walls instead of columns, with vents to allow water to flow through in case of storm surge. He estimated such upgrades added about $15,000 to the construction costs.

“If you want the luxury of living near the ocean, you have to pay,” said Mr. Gonzalez, 57.

The accompanying photo shows a house that won’t win any awards for architectural beauty:

The middle class will have to move inland or maybe to other states:

As older homes in the Fort Myers area are taken down, those that replace them will cost significantly more, Mr. Wilson said.

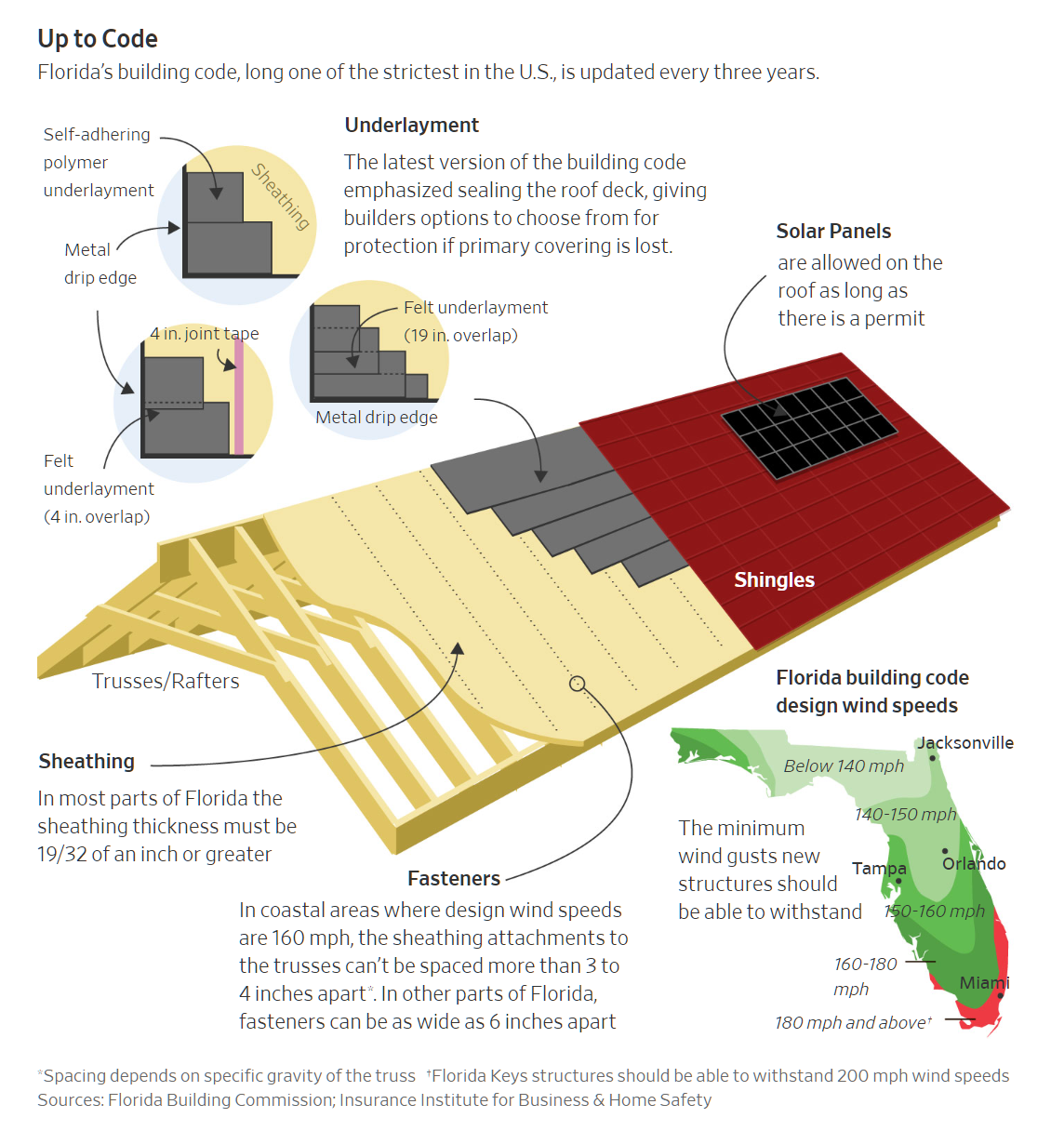

Here’s the required roof tech for a new house:

Nobody with money in Florida wants to live in an old house regardless of stormworthiness, so the process of hardening the coastal housing stock to survive the expected hurricanes shouldn’t be as wrenching as in states where tradition is valued.

Alternatively, of course, Floridians could refrain from building in vulnerable areas. But as long as there are people with sufficient funds to pay Cemex, I wouldn’t bet on restraint.

The minimum wind speeds are going to go up to at least mach 1. The lion kingdom is set on building a steel house when the rent money runs out. There’s nothing on the merits of concrete vs steel.

How about shipping container homes?

Recent storms have overtaken the colored map of wind exposure. Not sure when (or if) it will be updated, it has historically been a tug-o-war between the insurers and the builders, with builders wanting the less expensive construction.

The whole FL coast should require at least 160 mph design, and the flood maps should also be updated to reflect (at least) the two (three, pick a number) most powerful storms of the past 20 (again, pick a number) years. The panhandle and Big Bend have had weaker codes because builders have resisted the cost and the legislature has accommodated them.

Meanwhile, home prices (inflation, market) have gone up more than the “code premium” of $12-$15k EVERY YEAR recently.

The code in the panhandle has been 140 mph and homes built to it have fared pretty well structurally, but shingles have failed, perhaps due to workmanship as roofers have been skeevier than general contractors. Flood maps have been weaker than historical flooding would require, but I have not looked since our last home search in 2019.

Storm drainage is a chronic problem in many areas, systems being unable to handle typical 1 to 2 inches-per-hour thunderstorms which are common. This may require abandoning some of the land already developed because replacing widespread drain infrastructure is not feasible.

I saw one place after Ian that was now in the middle of a stream. Probably on a barrier island which shouldn’t have been developed in the first place. Not sure building codes would help that situation much.

I hear Bermuda is fairly bullet proof, due to strong building codes.

Personally, I think there are some places on Earth where humans just shouldn’t live. Like New Orleans, which is below sea level and has hurricanes. Or floodplains, like near Sacramento. Or at the very least, they should pay for their own insurance — no government subsidies when your place floods or burns.