From a couple of economists in Sweden, proving that sometimes peer-reviewed research must be rejected, “The Covid-19 lesson from Sweden: Don’t lock down” (Economic Affairs):

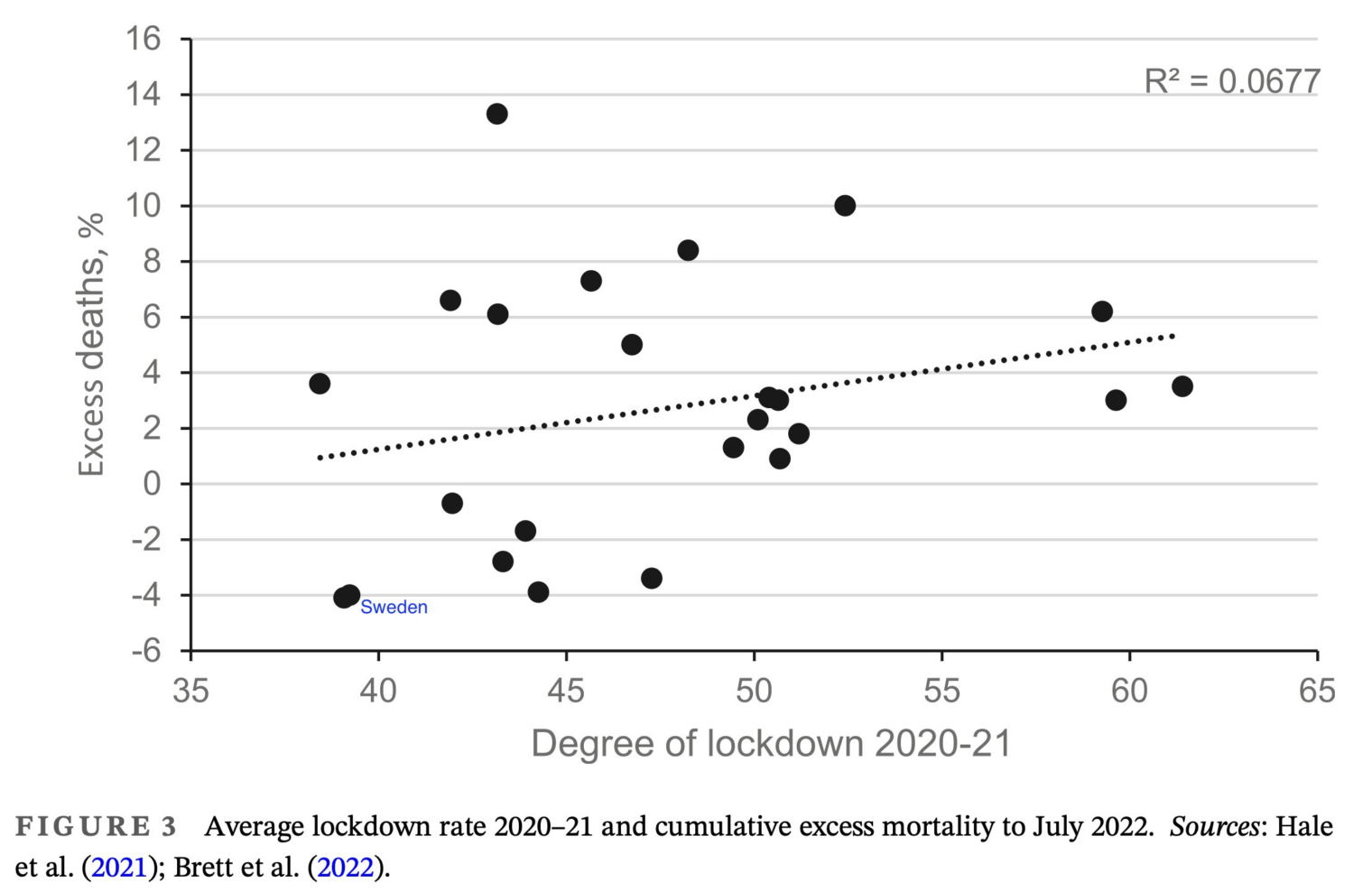

… countries with more stringent lockdown measures did not experience a lower death rate, as might be expected a priori.

Sweden, with an average lockdown rate of 39 for 2020–21, shows a weak cumulative GDP growth of 3 per cent during the two years 2020–21. Compared with an average annual pre-pandemic growth rate of 2.6 per cent, the Swedish economy lost approximately one year of growth. Countries with a higher lockdown rate lost between one and three years of economic growth.

There is a clear correlation between the degree of lockdown and the budget deficit for 2020–21. It shows the same pattern that emerged in Figure 4 for the relationship between lockdowns and GDP growth: the more restrictions, the deeper was the downturn in the economy and, consequently, the larger was the budget deficit.

In Sweden, with a lockdown indicator rate of 39, the total fiscal cost measured in this way was less than 3 per cent of GDP. In other words, Sweden managed to meet the European Union’s Maastricht criteria of no more than a 3 per cent budget deficit even at the height of the crisis. The corresponding budget deficit figure for the UK, with a lockdown rate of 50, was 27 per cent; for Italy, with a lockdown rate of 60, it was 17 per cent; and for France, with a lockdown rate of 48, it was 16 per cent.

Countries with weak public finances before the crisis experienced a further deterioration during the pandemic. After the pandemic, France had a higher public debt-to-GDP ratio than Greece did in 2009 at the start of the European debt crisis. In Sweden, the debt-to-GDP ratio at the end of 2021 amounted to 36 per cent, just slightly above the 35 per cent ratio before the pandemic. By the end of 2022, the Swedish debt ratio had fallen to 34 per cent and it is expected to fall below 30 per cent in the coming years.

By being less restrictive than other countries, Sweden was able to combine low cumulative excess mortality with relatively small losses in economic growth and continued strong public finances.

Here’s an annotated version of one of the figures from the article:

In other words.. the Swedes still think that they’re right!

Where is the non-Nobel Nobel prize in economics for Anders Tegnell and his not-so-merry band of MD/PhDs who said, in February 2020, “you might as well get used to SARS-CoV-2”?

The Swedes looked wrong for a long time, not because they were wrong, but because they made the separate mistake of mishandling nursing homes and care of elderly patients, which many other places also made. But their resulting excess death rate didn’t persist, as it did elsewhere.

Where is the non-Nobel Nobel prize in economics for Anders Tegnell and his not-so-merry band of MD/PhDs who said, in February 2020, “you might as well get used to SARS-CoV-2”? Uppsala Sweden!

Phil was also right on Covid from day 1 because he was both able and willing to interpret the data in an unbiased way & should share in any prize with Anders Tegnell. Am grateful that Phil shared his insights on this blog and enabled at least me to side step the Covid hysteria. Easily Phil’s finest hour.

This graph mostly shows excess bullshit.

Those of us who have a clue about bio and medical statistics know that “excess deaths” is a highly processed statistical measure which can be manipulated in a hundred ways till tomorrow.

This probably measures not how many people died but rather how many statistical shenanigans the “authorities” employed for propaganda purposes in more or less authoritarian countries. Which one can reasonably expect to correlate with degree of wholesale violation of civil rights (aka “lockdowns”) by the same authorities.