Let me recommend The Art Thief by Michael Finkel, a book about a French couple who stole roughly $2 billion (in pre-Biden dollars). Stéphane Breitwieser and Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus hit smaller museums over a 7-year period and hauled everything back to their apartment to enjoy. Since they didn’t try to sell anything, they were tough to catch, but of course they eventually were which is why we have the book (guess which one went to prison and which one successfully escaped by claiming to have been a victim under the control of the other).

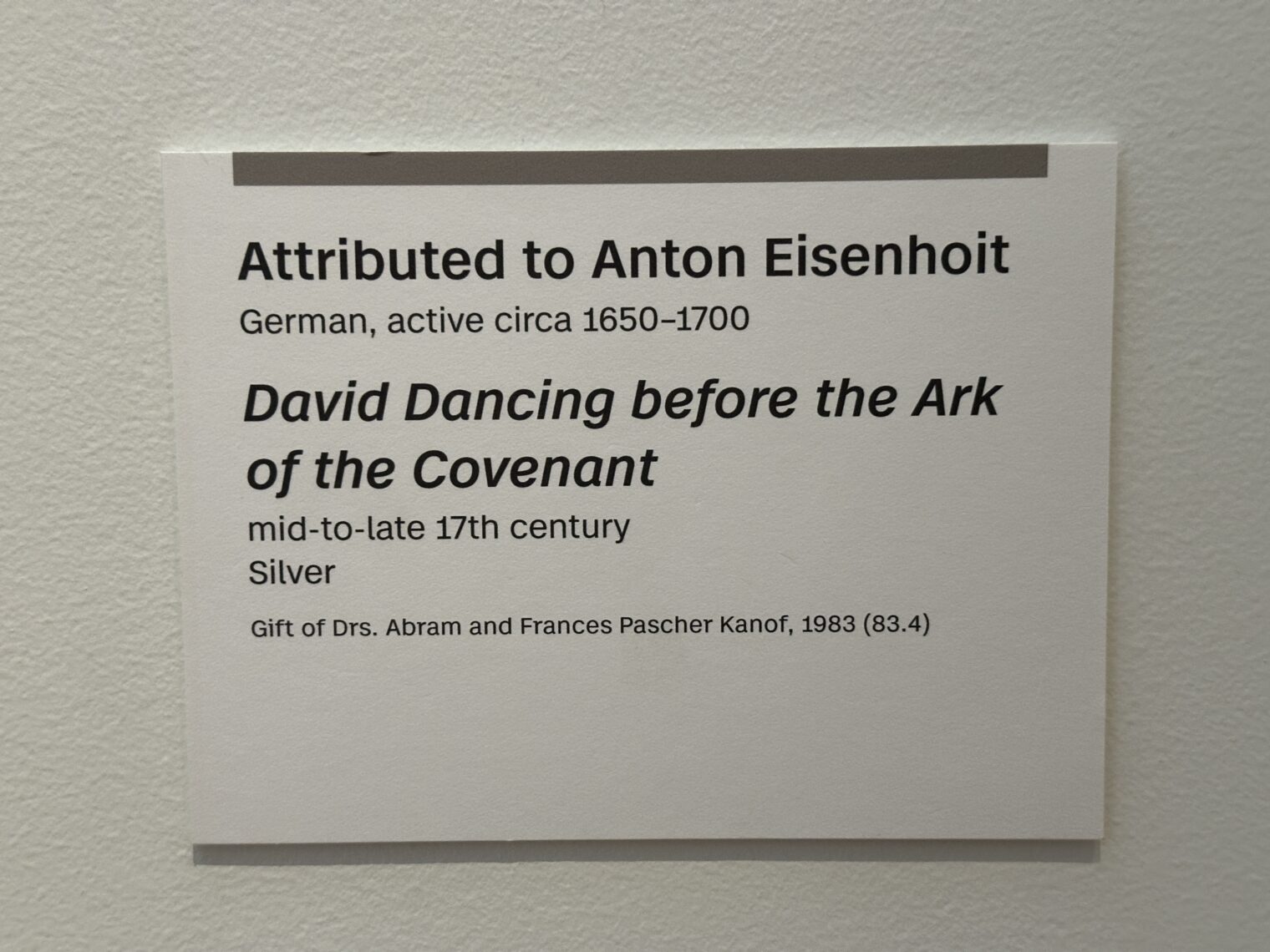

Here’s the kind of thing that they might have stolen. I saw it at the North Carolina Museum of Art while I was reading the book and thought that it would look great in the glass display cabinet of any Indiana Jones fan:

(Raleigh-Durham has become an Islamic area, but the museum has a sizable collection of Judaica.)

Breitweiser had a Swiss Army knife and Anne-Catherine had a huge purse. This was sufficient equipment for all of the thefts (which occurred perhaps just a few years before it would have been straightforward to attach an RFID tag to everything in a museum and then put sensors at all of the exits).

Breitweiser points out that art in a museum, rather than a private home, is unnatural:

He takes only works that stir him emotionally, and seldom the most valuable piece in a place. He feels no remorse when he steals because museums, in his deviant view, are really just prisons for art. They’re often crowded and noisy, with limited visiting hours and uncomfortable seats, offering no calm place to reflect or recline. Guided tour groups armed with selfie-stick shanks seem to rumble through rooms like chain gangs. Everything you want to do in the presence of a compelling piece is forbidden in a museum, says Breitwieser. What you first want to do, he advises, is relax, pillowed in a sofa or armchair. Sip a drink, if you desire. Eat a snack. Reach out and caress the work whenever you wish. Then you’ll see art in a new way.

The scale and pace of the thefts:

In the spring and summer of 1995, only a year after their first museum theft together, Breitwieser and Anne-Catherine find an incredible rhythm. They steal at a pace as fast as any known art-crime spree has been committed, outside of wartime. They hop between Switzerland and France, trying to keep at least an hour’s drive, and preferably two or three, between any places they hit. Even if they have to visit a couple of spots, museums are everywhere in Europe. And about three out of every four weekends, they successfully steal—a seventeenth-century oil painting of a war scene, an engraved battle-ax, a decorative hatchet, another crossbow. A sixteenth-century portrait of a bearded man. A floral-patterned serving dish. A brass pharmacy scale with little brass weights.

My favorite individual theft described in the book is a crime within a crime:

“Thief!” A word that no thief ever wants to hear shouted at him—shrieked—cuts through the bubbly conversations of the art-buying crowd at the European Fine Art Fair in the southern Dutch city of Maastricht. “Thief!” Even though he’s not stealing at the moment, Breitwieser flinches before realizing that the shouts are not directed at him. He watches as security officers rumble down the carpeted lane between booths. Heads in the exhibition hall turn. A thudding tackle and muffled blows bring even the owners out of their lounge-like areas. Richard Green, the iconic London dealer who is always granted prime placement at the fair, looks on, cigar in his mouth, as the thief is subdued and escorted away, the stolen item recovered. Entertainment over, Green returns to his stand, Renaissance oils arranged on pedestals, prices climbing from a million dollars. The dealer then discovers that one of his pedestals has a large empty space. Breitwieser’s giddy thought, as he and Anne-Catherine pull out of the parking lot a few minutes later, is that his car is currently worth more than the Lamborghinis they pass, if you include the souvenir in their trunk. The frame’s still attached, despite his stealing requirement; freak situations have their own set of rules. The artwork, an innovative 1676 unstill still life by Jan van Kessel the Elder, butterflies flitting around a bouquet of flowers, had hooked Breitwieser and Anne-Catherine from the art-show aisle, well outside Green’s booth. He’d never seen anything like it. The colors were incandescent. The work reeled them into the booth, through a mirage of shimmering hues that seemed impossible until they realized, up close, that the piece had been painted on a thin sheet of copper.

The European Fine Art Fair is a good place to covet items, though not to steal. The security unit is professional, with some undercover, Breitwieser says. Also, a potential deal breaker for Breitwieser, attendees are often searched at the exit, sales documents required. The copper painting sang to him and Green’s comeuppance felt ordained, but attempting a theft with almost zero chance of success is only the act of a fool. Providentially, a fool appeared as if on cue. With two piercing shouts, the fair shifted. The booths nearly emptied as the rubbernecking crested. Breitwieser was as surprised as anyone. Yet in the commotion that followed, he ascended into a sort of art-stealing nirvana, seemingly able to visualize the whole crime from above. The guards at the exit, he intuited, would abandon their post to assist the arrest. He’d bet a prison term on it.

The book says that there are roughly 50,000 art thefts per year, worldwide, with a total value in the single-digit $billions.

If you’d wondered about the veracity of Les Miserables…

In Switzerland, the guards had called him “Mr. Breitwieser.” In France, they shout his inmate number.

Within months of his arrest, the girlfriend has moved on. She’s pregnant with another man’s child and testifies against Breitwieser:

Anne-Catherine, dressed in a long black skirt, is called to testify after his mother, and she doubles down on total denial. She testifies, in a timid voice that Breitwieser says he’s never before heard, that she had not noticed any Renaissance works in the attic. She wasn’t present on his road trips. She never saw any art in his car. The two of them barely dated, she says. They were more like acquaintances. “He scared me,” says Anne-Catherine. Every day she was with him, she felt like his hostage. “He tormented me.”

(The hostage drove away from the apartment most mornings in a car and returned in the evening.)

More: Read The Art Thief.

All the CEO’s protecting their wealth from taxes by buying fine art would not be pleased. As one who payed a fortune in CA dividend taxes during our only year of positive interest rates since the deficit crossed $12 T, fine art is looking like a better deal than treasuries, as well as the deduction our CEO gets from donating to a museum.

I am ruling them out as the culprits behind the Stuart Gardner museum heist! They don’t sound like they dress as police officers!

https://www.wgbh.org/news/local/2024-03-18/34-years-after-gardner-heist-the-museums-director-of-security-is-still-on-the-case

guess which one went to prison and which one successfully escaped by claiming to have been a victim under the control of the other! My guess would be the woman put the man under a spell and the woman is in jail and the man is the victim.

TS: Now you’ve spoiled it! Indeed, the man was without agency and, therefore, blameless.

At first I thought it was the following case:

https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/de-kooning-art-theft