When the typical business is hit by a strike it is able to continue operating at a reduced capacity via the use of supervisors and/or replacement workers (airlines are an exception due to FAA regulations; see “Unions and Airlines”). Why are Atlantic and Gulf Coast U.S. ports completely shut down by the International Longshoremen’s Association strike for a 77 percent wage increase to compensate them for the inflation that the Biden-Harris administration says does not exist (CBS; 77 percent is pretty close to the rise in the cost of buying a house during the Biden-Harris years, considering the increase in price and the increase in mortgage rates).

The port operators have offered a 50 percent wage increase to compensate workers for non-existent inflation and the strike relates to the 77 v. 50 number.

Today’s question is why ports are shut down. Managers aren’t part of a union. Why can’t the management/supervisory staff at the ports operate the cranes and unload container ships at a reduced rate compared to if a full staff were available? Continued operations at a reduced capacity is what happened after Ronald Reagan fired America’s striking unionized air traffic controllers (state-sponsored NPR).

Historically, American employers had the right to hire permanent replacement workers for striking union workers, though the Biden-Harris administration is trying to eliminate that right (source (2023)):

The law of the land for the last 60 years has permitted employers to permanently replace employees engaged in an economic strike, providing employers with the right to hire workers to continue business operations in response to a union’s use of its most potent economic weapon. In its decision in Hot Shoppes, Inc., 146 NLRB 802 (1964),the Board held that employers may lawfully hire permanent replacements and that this action is not inherently destructive of the right to strike under the National Labor Relations Act (“Act”), making the employer’s motive for hiring the replacements immaterial. Accordingly, an employer does not need to prove it had a business necessity when hiring permanent replacements or that the employer’s ability to continue operations during a strike required the hiring of the replacements. Rather, the GC has the burden of proving the employer violated the Act by permanently replacing strikers because of an “independent unlawful purpose.”

Even if Biden-Harris makes it illegal for the ports to hire permanent replacements, why can’t the ports operate with temporary replacements? The container cranes are highly automated, which has, in fact, been a big motivation for fighting between unions and management (the “workers” aren’t actually required for the “work” because robots do a better job at running the cranes).

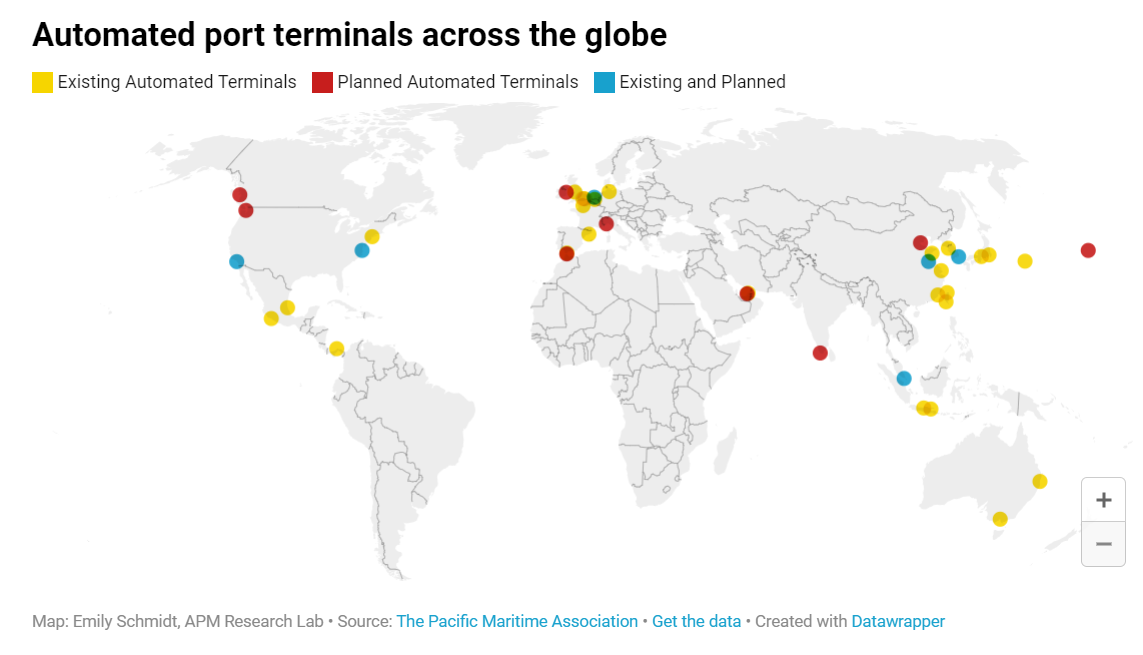

It looks like ports are mostly automated in other parts of the world, e.g., China, Europe, and Central America (source):

But the U.S. does have some ports that you’d think could be operated by managers. From the same article:

Currently, only four out of 360 commercial ports in the U.S. have at least semi-automated terminals: Los Angeles, Long Beach, New York & New Jersey and Virginia.

Why wouldn’t NY/NJ and Virginia be up and running with managers staring at the monitors while the computers do all the real work?

Apparently crane operators are skilled labor and not just anyone can do it. If someone drops something, it can kill someone or do hundreds of thousands of dollars (maybe millions) in damages.

At least on the west coast, union longshoreman jobs are well into the six figures (Police/fireman/lawyer kind of money)

I have heard that if they want to exert pressure short of a strike, they sometime drop a container or two. They also have the ability to totally shut down trade. They usually negotiate quite effectively.

Air traffic control is also skilled labor and, as noted in the original post, FAA managers were able to take over and run ATC after the union members went out on strike. Why couldn’t the same thing happen at a port?

Working ATC requires a specific certificate, just as a pilot or instructor or mechanic must have a certificate: https://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/avs/offices/aov/credentialing (apparently, the supervisors at FAA ATC had these certs)

I’ve always thought that a much of the replacement labor, at least temporarily, was provided by military controllers who were a) already federal employees and b) can be literally ordered to go anywhere for any length of time. While the Navy might have a few qualified operators, the docks aren’t federal facilities, and the ratio of military to civilian operators is probably much smaller than the ratio of military to civilian controllers in the early 1980s (i.e., pre-BRAC and very early deregulation).

“DONALD DEVINE: We had to get more people. We had to steal them from the military controllers.

SIMON: They were putting air traffic control students through accelerated tracks, trying to get them ready.

DEVINE: We had to try to go to people who retired to come back.”

Phil ‘FAA managers were able to take over and run ATC’ means FAA managers could actually do the job. If that is not true here, then managers cannot replace anyone. Case in point, my manager could not do the work I do, so I could not be replaced.

Also: to be fair to the longshoremen: they pretty much have to live near the coast and have to actually show up at work in person, so their real estate costs are going to be “Coastal Ridiculous” and not average.

Also: is this a tacit endorsement of Trump by the longshoremens’ union? It’s October surprise season and this could potentially trash the economy.

Although the amount of the raises is a big issue (and the one that gathers most headlines) the automation issue, and specifically what it means for the future pension obligations of the ILA is the most important from the union perspective.

As some articles point out, major ports outside the US have automated over the years and can operate significantly smaller manpower. If the US ports were allowed to adopt this as soon as practicable the ILA union membership would rapidly decrease. This is a big problem for the ILA since it offers a very nice defined benefits pension plan. Taking a page out of our friends at social security, the plan was designed using math that assumes steady or slightly increasing union membership from now until the future. Ooops.

In order to resolve this strike raises will be handed out. But the real negotiation is revolving around how a smaller future workforce would support the significant pension promises already made by the ILA over the last 70 years.

No matter where you come out on unions in general or the ILA in particular I think this is an interesting situation. Automation is coming for jobs and this union is going to try to use what leverage it has available to it to get some kind of settlement.

Greenspun needs to get in there & save the cargo, along with airdropping supplies in NC.

He is already doing just that, dropping starlink terminals one by one out his R44 helicopter.

If any CEO demands exuberant compensation and corporate board denies it and he/she go on strike, I am ready to take on the job, at 90% of CEO take.

I am retired and available. Willing to cross labor line. Have not the slightest interest in longshoreman union.