“Hailing a Car in Midtown Manhattan is Becoming More Expensive” (NYT, January 5, 2025):

Many of the vehicles that crowd the tolling zone are taxis and cars for ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft.

The new tolls will not fall on the drivers of those vehicles, who are often struggling to make ends meet. Instead, passengers will be charged an additional amount for each trip into, out of and within the zone. (Even before the new pricing began, passengers already paid congestion-related fees of up to $2.75.)

Riding in a taxi, green cab or black car will now cost passengers an extra 75 cents in the congestion zone, which runs from 60th Street south to the Battery. The surcharge for an Uber or Lyft will be $1.50 per trip.

I want to focus on “the new tolls will not fall on the drivers of those vehicles”. Let’s consider Eric Cheyfitz, the Cornell professor who teaches Gaza, Indigeneity, Resistance:

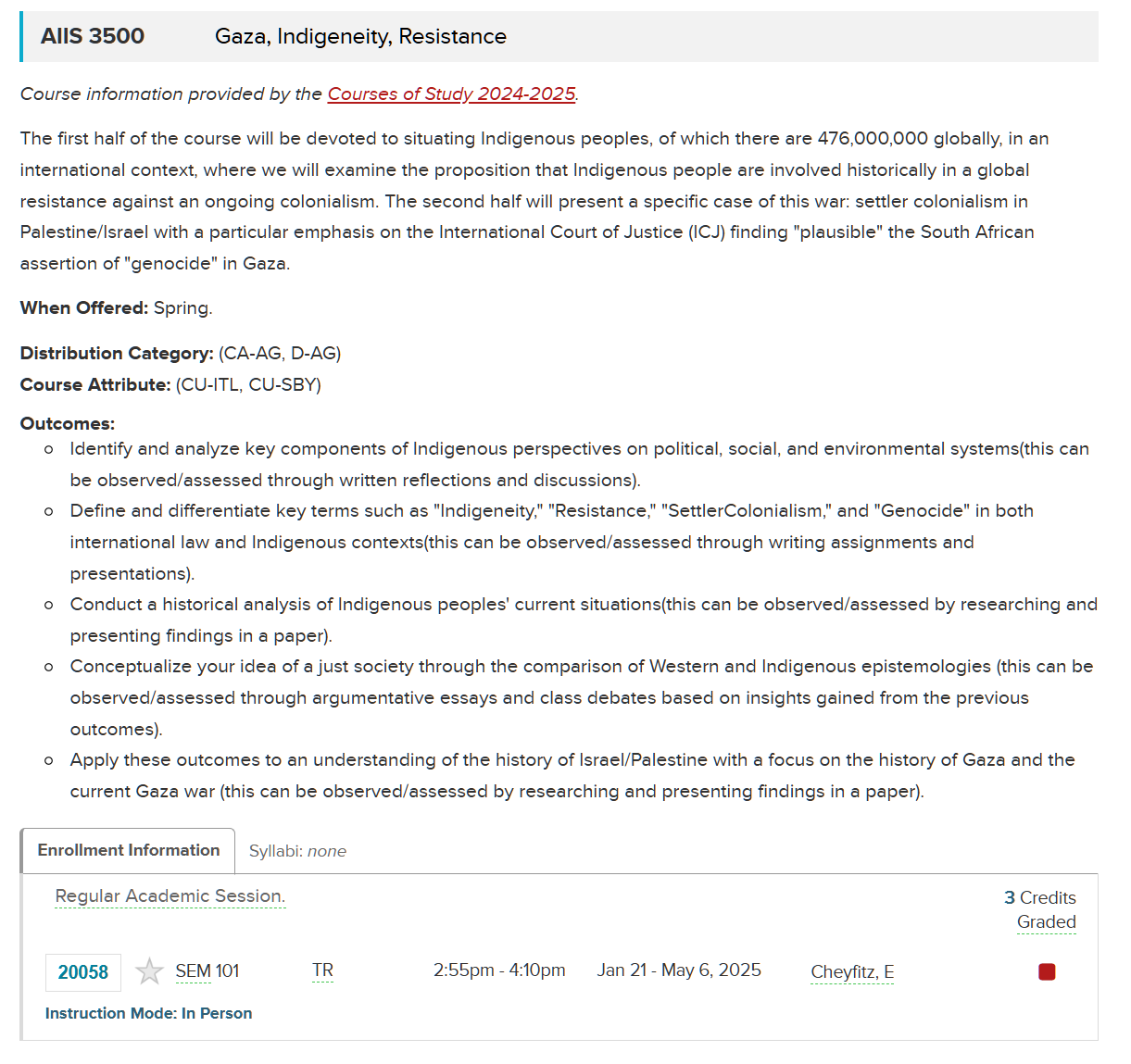

The first half of the course will be devoted to situating Indigenous peoples, of which there are 476,000,000 globally, in an international context, where we will examine the proposition that Indigenous people are involved historically in a global resistance against an ongoing colonialism. The second half will present a specific case of this war: settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel with a particular emphasis on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) finding “plausible” the South African assertion of “genocide” in Gaza.

(There are 476 million Indigenous people in the world, but fully half of the course will be devoted exclusively to 2 million supporters of Hamas, UNRWA, and Palestinian Islamic Jihad.)

Prof. Cheyfitz is visiting some pro-Hamas faculty at NYU and is considering taking an Uber for a 15-block trip to a restaurant. His/her/zir/their alternative is walking or taking the subway. Suppose that Prof. Cheyfitz is willing to pay no more than $20 for a car ride before he/she/ze/they will hoof it. If the city imposes an additional $1.50 fee (on top of existing congestion fees, car registration fees, taxes, etc.), doesn’t that reduce the maximum revenue that a driver can obtain for the trip? I don’t see how the money taken by the government can not come out of some combination of Uber’s pocket and the driver’s pocket. Consumers always have alternatives, not only walking and public transit but also deciding to stay put. (And, in fact, one express goal of the fee is to reduce the number of trips that Uber/Lyft customers will take. If successful, doesn’t that mean the tolls actually did “fall” on the drivers?)

As a thought experiment, suppose that the new fee were $1,000. Nearly all consumers would decide to stay put or use public transit or use a personal/family car. With the service priced only for billionaires, there wouldn’t be work for more than 10 Uber/Lyft/taxi drivers in the entire city. With no limit on who can apply for these 10 jobs there wouldn’t be any reason for the job to pay any better than it does now. The impact of a $1.50 fee is much smaller, of course, but I think the analysis works in the same way.

The Cornell class in case it is memory-holed: