A friend’s daughter is a passionate progressive and, after completing an expensive degree at an elite university, signed up as a public middle school engineering teacher. Things haven’t been going well. “What percentage of her students are easy-to-teach white or Asian native speakers of English?” “Zero,” answered her dad. “They’re all either Black or immigrants. Half of the students speak only Spanish.”

All of the work for the course is done in the classroom/lab and, therefore, no homework is required. At least half of the students did nothing, goofing off in class and turning nothing in. “I can’t grade their work because they didn’t submit any,” says the daughter, ” so at least half of the class should get Fs.” She talked to some of the veteran teachers, however, and they advised her to give everyone in the class at least a C. The paperwork associated with a D or F grade would be onerous.

The father is an Obama-style Democrat (bigger government, Rainbow Flagism, but not necessarily Biden/Harris-style open borders). He volunteered that the core problem with our public schools nationwide is chronic underfunding. He believed that in the good old days of American K-12 the schools had vastly more money per student. He and his daughter both thought that most of the problems would disappear if the class sizes were reduced to half of the current levels (i.e., double the number of teachers).

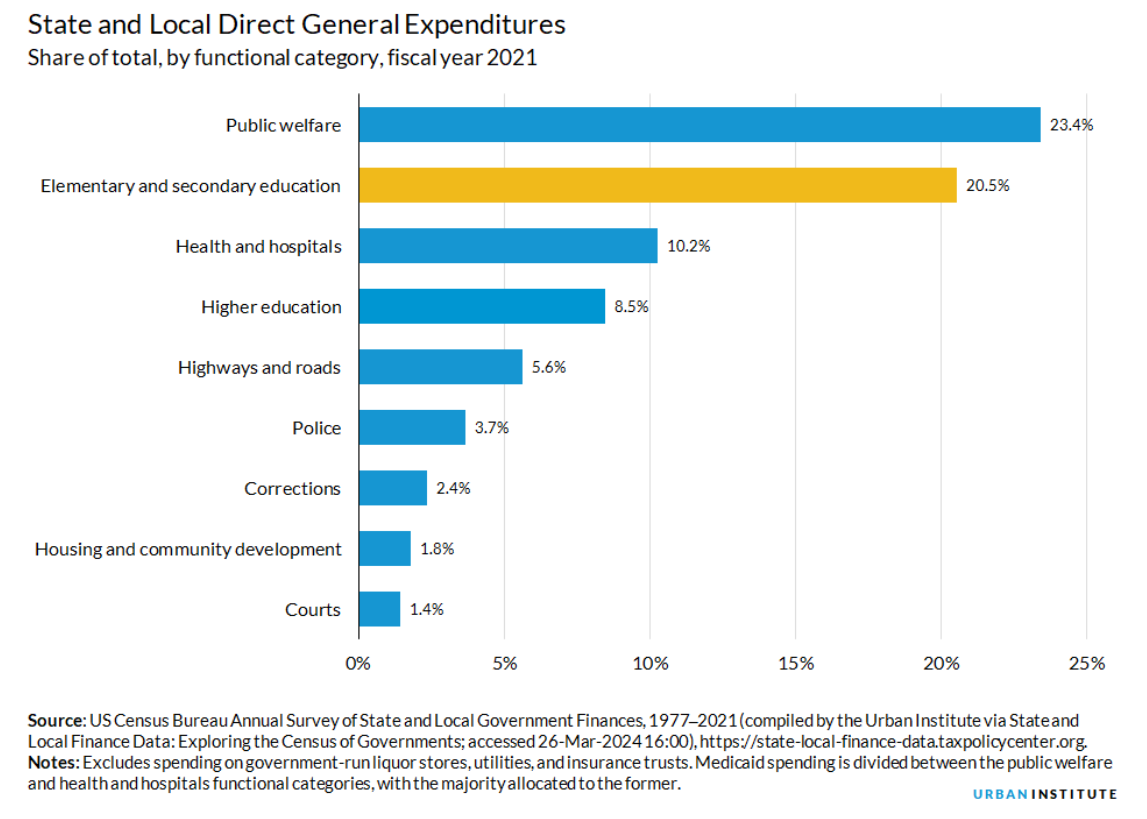

Urban Institute offers some trends. State and local governments now spend more on “public welfare” than on schools:

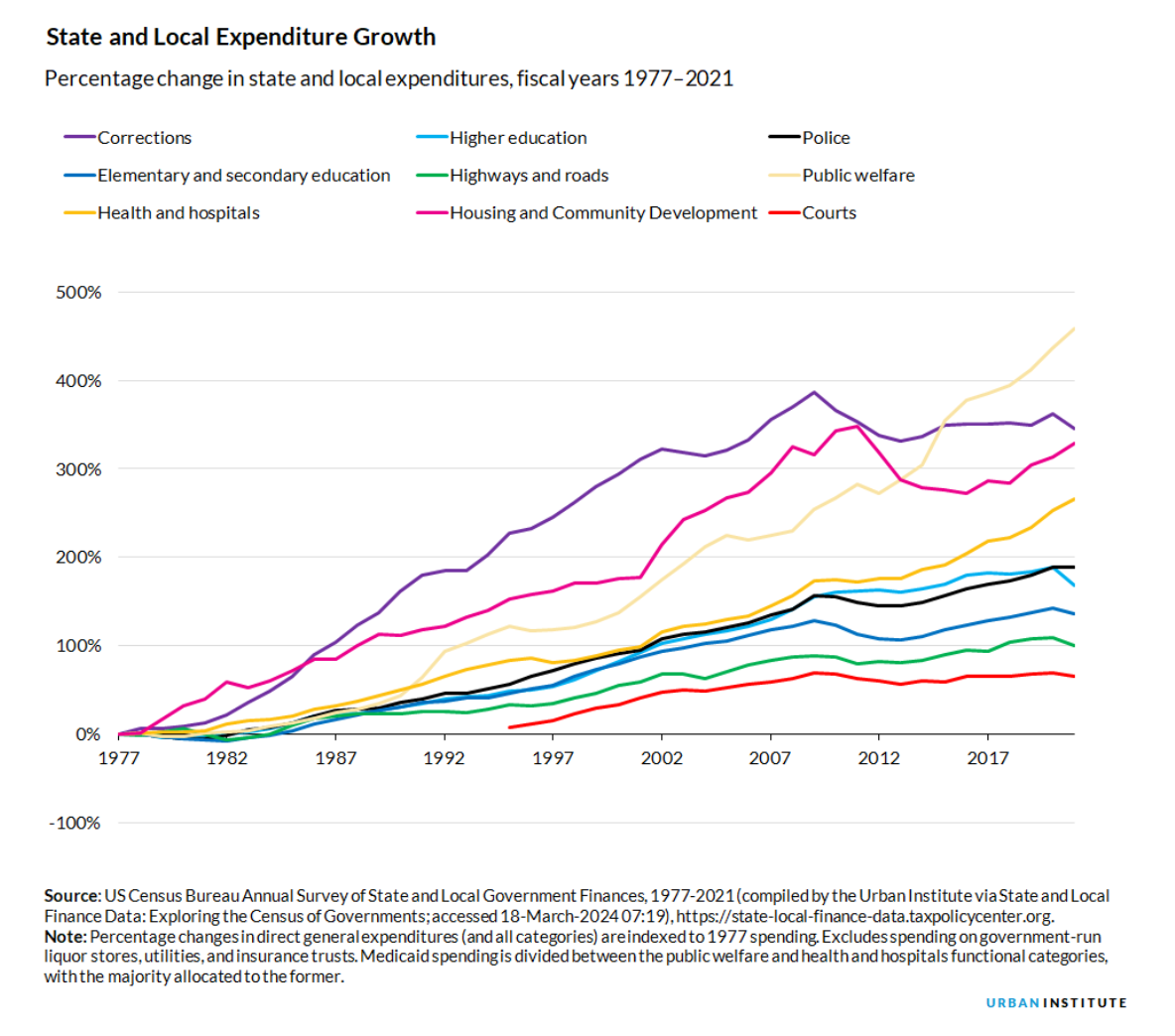

Public welfare is also the champion for inflation-adjusted spending growth (“health and hospitals” have also grown and would also have been considered “welfare” in the bad old days):

Inflation-adjusted spending on K-12 has grown by 136 percent compared to the purportedly good old days of school funding in 1977. (Perhaps it doesn’t matter for a growth comparison, but most numbers for “per-pupil spending” understate what society spends on K-12 because they don’t include the capital costs of building or renovating schools.)

Circling back to the grade inflation issue, I wonder if it is time to trot out my oft-expressed opinion that teachers shouldn’t grade their own students. There should be a neutral third party (maybe simply a teacher at another school) who does the grading while the teacher is purely a coach to assist students with doing well when they submit material to the neutral evaluator. (See “Universities and Economic Growth” from 2009, for example.)

Loosely related, a “Failure is not an Option” frame around an EDUKTOR license plate (Illinois), captured in the Juno Beach Pier parking lot:

See “Back to school in Chicago: fewer than 1-in-3 students read at grade level” for how, apparently, giving students the Ds and Fs when they’re at the D and F level of achievement is not an option.

> the core problem with our public schools nationwide is chronic underfunding.

A family with 2 kids requires ~$140k income to be net contributors (ie: fund govt + $15k per student-year school fees).

Where does the funding come from in a neighborhood of “newcomer” families, receiving welfare, each with 6-8 kids attending school?

In 2024, 75% of immigrants were between 18 and 64 years old. Although immigrants sometimes have larger families than those born in the US, 6-8 children are a gross exaggeration.

Reference: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states-2024

Phil, I was having my annual Kwanzaa brunch today and one of my favorite people was able to attend (Pocahontas Warren). We both had a great chuckle after reading about the dimwitted daughter of your friend. Clearly, she could use some guidance, because she clearly doesn’t have much natural ability.

For starters, she made a really poor career choice. Classical education is for dummies. Smart folks like me learned early on that the path to success is through a PhD in Black Studies with a minor (or major) in Plagiarism. That’s how you become a Leader and President of Harvard. But, Pocahontas suggests that she still has time to course-correct and that path involves lying, cheating and stealing, something that Pocahontas learned early on. We really wish her all the best, but she’s off to very poor start, so we aren’t particularly hopeful.

There was no such thing as engineering in middle school 40 years ago. Suspect it’s a toy class like many others during that age. It was devilishly hard to perform any kind of algebra in those days.

@Lion: “There was no such thing as engineering in middle school 40 years ago. Suspect it’s a toy class like many others during that age.”

Surely, the darling students are given take-home laptops so they can do their highly technical assignments (and watch porn or sell on the street for pocket money).

I have short story to relate. I am a little fuzzy on the details, but here’s the gist of it. In IIT Kanpur sometime in late 2000s, an undergraduate student committed suicide because he was afraid he might fail a course. He was an above-average student there. The story became pretty big in the media. The professor was super-pissed that the students are resorting to histrionics instead of studying harder, or just accepting the tough grades. The next time he offered the course, he graded even harder and taunted that students should go the media if they are dissatisfied.

https://www.usnews.com/education/best-global-universities/indian-institute-of-technology-iit-kanpur-506622

#847 in Best Global Universities

For comparison, MIT is ranked #2 and University of Florida is #109.

India’s education system is, essentially, the worst in the world:

https://educatedtimes.com/introduction-a-complex-educational-relationship/

“India’s sole flirtation with PISA came in 2009. Rather than participating nationwide, India was represented by two states – Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh. These weren’t random selections; they were among India’s better-performing states educationally, particularly Tamil Nadu with its robust educational infrastructure.

The results, however, were nothing short of shocking. Both states ranked among the bottom five participants globally, with scores significantly below the OECD average. Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh ranked 72nd and 73rd respectively out of 74 participants, outperforming only Kyrgyzstan.”

I have stated facts and will not comment further.

@FB, overall low ranking of IIT Kanpur can be explained by its failing wokeness score, based on @PhilG Fan comment. I am sure that wokeness categories at least 90% of us news and world report’s ranking system. Jokes aside, when I see graduates from low-ranked world universities holding top positions at places like MIT and Princeton’s IAS and giving them high ranking I think whether the rankings are good enough approximations of colleges’ worth.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/28/business/us-immigration-trump-1920s.html

You’re describing what America “might look like with zero immigration” according to NYT.

That is a great story about how the U.S. was improving, e.g., “First Mexicans, some undocumented, came to Marshalltown in the 1990s to work at the pork processing plant. After a high-profile immigration raid there in 2006, refugees with more solid legal status arrived from Myanmar, Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo.” (Instead of vacationing in the hellscapes of Merida, Cancun, or San Miguel de Allende, for example, Americans can enjoy safety and cultural enrichment in “Myanmar, Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo”.)

It’s also heartwarming to learn about how the U.S. is mining out the human resources of Ukraine so as to harm Ukraine’s ability to defend itself from the Russian military: “Sergii Fedko and his wife, Tetiana, came to Marshalltown in 2023 along with five other Ukrainian families under an immigration parole program for their war-torn country. Mr. Fedko, a power plant engineer in Ukraine, was quickly hired at a local architecture firm as a designer and draftsman. Ms. Fedko works at a day care center, where she is beloved by her charges. Their three sons are enrolled in school; the eldest excel at soccer and swimming. They bought two cars and a fixer-upper house.” (those three sons will never serve in Ukraine’s army)

Also, without slaves who will pick the cotton? “But there are limits to how much [landscaping] customers will pay for decorative shrubs, and they may opt to go without.”

There was an article in the French media about the continously increasing prices of ski holidays in the French Alps. A reader posted the following comment (in my translation):

“The ski holidays are the only time of the year when we can be among Europeans. We can leave our skis unattended without fearing their theft, there’s no aggresion, we can go to after-ski with the women-friends, etc. A small peek at what our life could have been without immigration.”

Adso: Club Med is like that. Most of the guests are white French-speaking people from pre-Islamic France and pre-Islamic Quebec heritage. The rest are at least reasonably wealthy Americans, etc. So it is like traveling back in time culturally. (Somali day care profiteers in Minnesota are obviously rich enough to afford Club Med, but I guess they’re not interested.)

@philg: “Somali day care profiteers in Minnesota are obviously rich enough to afford Club Med, but I guess they’re not interested.”

They’re Somalis in Minnesota are former “Sun People.” They are now “Ice People” and are uninterested in Club Med or any equatorial location.

Europeans have their skiing and sun bathing, while Somalis cultural enrichment includes the aqeeqa, or the Islamic tradition of the sacrifice of a goat on the occasion of a child’s birth.

Every teacher I know would welcome someone else to do their grading for them.

> The paperwork associated with a D or F grade would be onerous.

Try teaching special education, where failing a student is de facto illegal