A third post about the core topic within House of Huawei: The Secret History of China’s Most Powerful Company …

The company went Full Vegas:

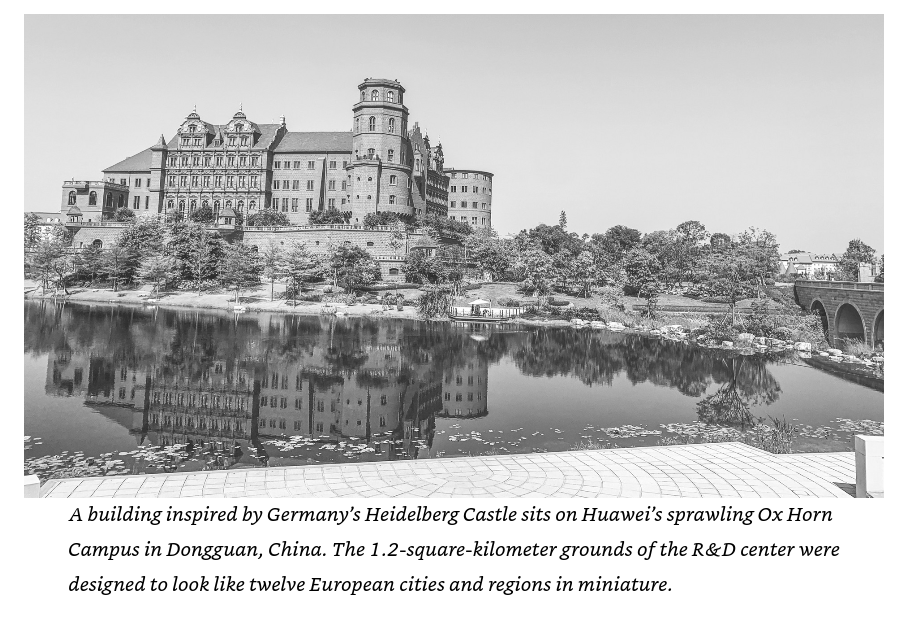

Back when he had visited the United States in the 1990s, Ren Zhengfei had been struck by the grand architecture of Las Vegas, modeled after Roman palaces. He’d remarked that Las Vegas might be the most beautiful city in America. Now in the hinterland to the north of Shenzhen, he began building his own version. Huawei had outgrown its Shenzhen headquarters by 2016, with 180,000 employees globally and counting, and Ren’s team was searching for more space. This was hard to find in Shenzhen, which was a thicket of skyscrapers by now, with soaring property prices. They found what they were looking for in Dongguan, Shenzhen’s up-and-coming northern neighbor, which still had stretches of undeveloped land. Eager to woo the company, Dongguan officials offered Huawei a prime 1.2-square-kilometer tract of verdant land on the south shore of a lake. Ren’s younger brother, Steven Ren, was put in charge of the construction of these new Dongguan R&D grounds, which they called Ox Horn Campus. They hired Japan’s Nikken Sekkei, the world’s second-largest architectural firm, which produced a fever dream of a design: Ox Horn would be built to look like twelve miniature European cities, including Paris, Verona, Bruges, and Oxford. They would re-create some of the greatest hits of Western civilization, including Germany’s Heidelberg Castle and France’s Palace of Versailles. “What is important is not simply to copy certain architectural styles but to make them truly beautiful,” Steven Ren wrote of the project. Huawei would overlook no detail. The architects were proud that none of the roofs of the 108 buildings were identical. Reflecting an eye for historical accuracy, some of the shingles were slate, others terra-cotta or copper. The pitches of the roofs ranged from twenty to ninety degrees. The buildings were faced in a range of materials, including granite, sandstone, limestone, dolomite, brick, and stucco (for Verona and Grenada). There were, of course, some concessions to modernity, such as treating the porous stones to prevent mildew and algae growth. Facial-recognition gates were installed at the entrances.

Huawei hired 150 Russian painters to cover the halls’ ceilings and walls with Renaissance-style murals, with the painters joking that even the Kremlin didn’t have such beautiful corridors. Someone stocked the lake by the castle with black swans—a reference to the financial term for worst-case scenarios that are hard to forecast. Ren so frequently warned his staff to look out for black-swan events that, at some point, the bird became Huawei’s unofficial mascot.

Huawei today makes the world’s best smartphone in terms of camera quality. DXOMARK:

The founder didn’t want to get into this business:

In Huawei’s early days, Ren had been less than enthused at the idea of hawking handsets—which were called “terminals” in Huawei-speak—as he considered it too far afield from the company’s core businesses of switches, routers, and base stations. “Huawei will not make a mobile phone,” Ren once insisted indignantly. “Anyone who talks this nonsense is going to get laid off!” Even after Huawei began pursuing smartphones seriously, Ren feared wasting money on marketing and was often harsh on the company’s head of consumer products, Richard Yu, or Yu Chengdong. “People always say I criticize Yu Chengdong,” Ren remarked to staff. “Actually, my criticism of him is my way of caring for him.”

How tough is it to break into the premium phone market? From 2016:

To close the gap with Samsung would be a formidable challenge: Samsung was pouring $14 billion a year into advertising, more than Iceland’s GDP.[

There is a chapter on Canada holding Meng Wanzhou, the founder’s daughter from his first marriage and Huawei CFO, hostage at the request of the U.S. government, but that’s been extensively covered elsewhere. (The allegations against Huawei had to do with selling equipment to Iran.)

The U.S. also strong-armed the Taiwanese into shutting out Huawei, which merely resulted in the improvement of Chinese domestic capabilities. May 2020:

TSMC had supplied Huawei for years, but now, under the threat of sanctions, it could not risk losing access to US technology to run its own operations. TSMC shut its doors to Huawei. Huawei’s only hope now was for China’s domestic chip foundry, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation, or SMIC, to learn how to produce advanced chips at lightning speeds. This was a real Hail Mary: SMIC had been endeavoring for two decades to advance its technologies but still lagged several generations behind global leaders in advanced chipmaking. This second round of US sanctions cut deep. In July 2020, citing the new US sanctions, the UK announced that it was reversing its position on Huawei and would remove all Huawei equipment from the nation’s 5G networks by the end of 2027.

Whoever was running the U.S. during the Biden-Harris was just as hostile to Huawei as Donald Trump had been:

If there had been hopes among Huawei’s executives that Biden would be softer on China than Trump, they were quickly dispelled. The Biden administration was more careful in its rhetoric to avoid fanning anti-Chinese racism. It didn’t use terms like “Clean Network” and “Clean Nations.” But in many ways, it was only picking up where the Trump administration had left off and deepening the efforts to contain China.

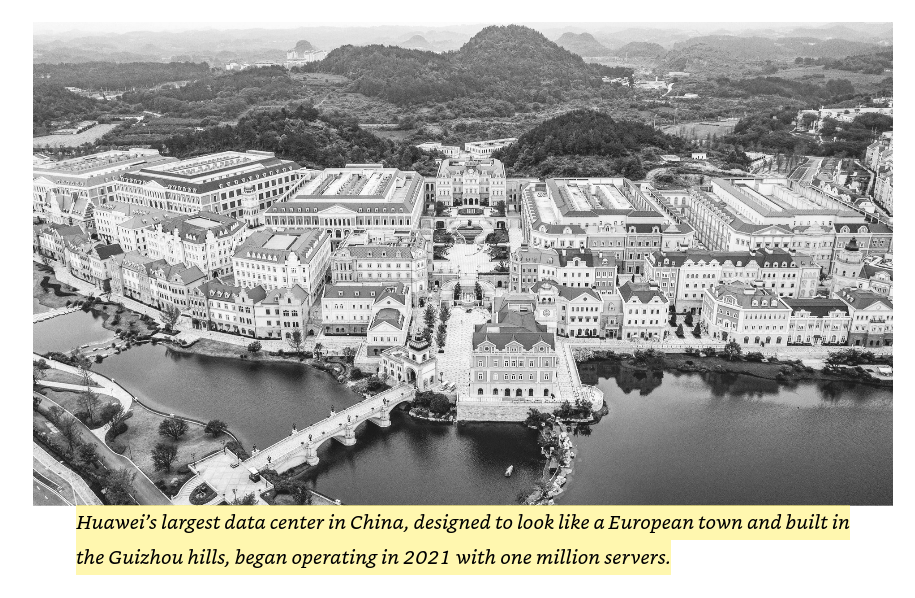

Finally, check out the aesthetics on this data center that Huawei built:

Did the book include a picture of a roof with a pitch of 90 degrees?