More from John Morgan and Philip Greenspun on using AI when doing web development…

Intro from Philip

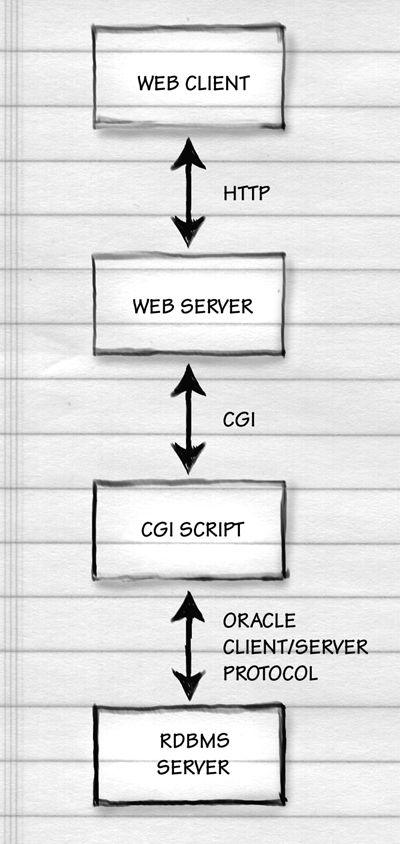

In 1994, when I built my first web services backed by relational database management (RDBMS) systems, every request to an HTTP (Web) server resulted in an expensive fork, i.e., the spawning of a new process within the Unix operating system. If the request was for a small computer program to run, rather than a static file from the file system, that resulted in a second fork for a CGI script. If there was a need to refer to information in an RDBMS, such as Oracle, the CGI script would initiate the login process to the RDBMS, which would check username and password and… initiate another fork for a new process to handle what would ordinarily be 8 hours of SQL requests from a human user at a desktop in the 1980s client/server world. So that would be three new processes created on the server in order to handle a request for a web page. All would be torn down once the page had been delivered to the user. Consider how much longer it takes to start up Microsoft Word on your desktop computer than it does for Word to respond to a command. That’s the difference between starting up a program as a new process and interacting with an already-running program. Here’s an illustration of the four processes ultimately involved. The top one is the user’s browser. The three below that were spawned to handle a single request.

NaviServer (later “AOLserver” after NaviSoft’s acquisition by AOL) was the first web server to combine the following:

- multi-threading, enabling a request for a static file to be served without a fork

- internal API, enabling small programs that generated web pages to run within the web server’s process, thus eliminating the CGI fork

- pooling of database connections, e.g., four persistent connections to an RDBMS that could be used to handle queries from thousands of requests, thus eliminating the fork of an RDBMS server process to handle a “new” client on every request

The available languages for page scripts that could run inside the AOLserver were C (macho, compiled, slow for development, potential to destroy the entire web server, not just break a single page, with one mistake; see the API) and Tcl (embarrassing to admit using, simple, interpreted, safe; see the API).

As the architect of the information systems that would be available to all of Hearst Corporation‘s newspapers, magazines, radio stations, TV stations, cable networks, etc., I selected the then-new NaviServer in late 1994 in order to achieve (1) high performance with minimal server hardware investment, and (2) high developer productivity. The result was that I developed a lot of code in Tcl, a language that I hadn’t used before. It didn’t seem to matter because the Tcl was generally just glue between an HTML template and a SQL query. The real programming and design effort went into the SQL (are we asking for and presenting the correct information? Will comments, orders, and other updates from hundreds of simultaneous readers be recorded correctly and with transactional integrity in the event of a server failure?) and the HTML (will the reader be able to understand and use the information? Will comments, orders, and other updates from the reader be easy to make?).

Just a few years later, of course, other companies caught up to AOLserver’s threaded+scripts inside the server+database connection pools architecture, most notably Microsoft’s Internet Information Server (IIS). Eventually the open source folks caught up to AOLserver as well, with a variety of Apache plug-ins. And then I persuaded America Online to open-source AOLserver.

Here we are 32 years later and I’m still running code that we wrote at Hearst. The company was interested in publishing, not software products, so they graciously allowed me to use whatever I wrote at Hearst on my own photo.net web site and, ultimately, to release the code as part of the free open-source ArsDigita Community System (adopted by about 10,000 sites worldwide, including some at Oracle, Siemens, the World Bank, Zipcar, and a bunch of universities).

[One fun interaction: in 2012, I was at a social gathering with a developer from the Berklee School of Music (Boston). He talked about some legacy software in a horrible computer language that nobody knew that they had been using for 10 years to track and organize all of their courses, students, teachers, assignments, grades, etc. They’d had multiple expensive failed projects to try to transition to newer fancier commercial tools and finally, at enormous cost in dollars and time, had succeeded getting away from the hated legacy system. It turned out that he was talking about the .LRN module that we’d developed for the MIT Sloan School in the 1990s and that was then rolled into the open-source toolkit. I kept quiet about my role in what had turned into a pain point for Berklee’s IT folks…]

Our Project

As part of our experimentation with AI and web design, we asked LLMs to do some redesign work on philip.greenspun.com. They all came back and said that it would be necessary to modify the HTML flying out of the server and not merely an already-referenced CSS file. It would be technically feasible, of course, to write a script to run on the server to open up every HTML file and add

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1">to the HEAD of every document before writing it back into the file system. This would, however, have the side effect of updating all of the last-modified dates on files that, in fact, hadn’t been touched for decades (fixable with a little more scripting) and also creating a blizzard of updates to the git version control system.

The server was already set up with a standard ArsDigita Community System feature in which a Tcl procedure would be run for every HTML file request. This obviously reduces performance, but it enables legacy static HTML pages to be augmented with navigation bars, comment links, comments pulled from the RDBMS, advertising JavaScript, extra footers or headers, etc. Instead of modifying every HTML file under the page root, in other words, we could simply modify this function to add whatever tags we wanted in the head.

The questions:

- Would an LLM be able to understand a Tcl program that had grown over the decades into a confusing hairball?

- Would an LLM be able to do a minimalist modification of the program to insert the one line that was needed?

- Would an LLM be able to reorganize the software for improved legibility, modularity, and maintainability?

The original

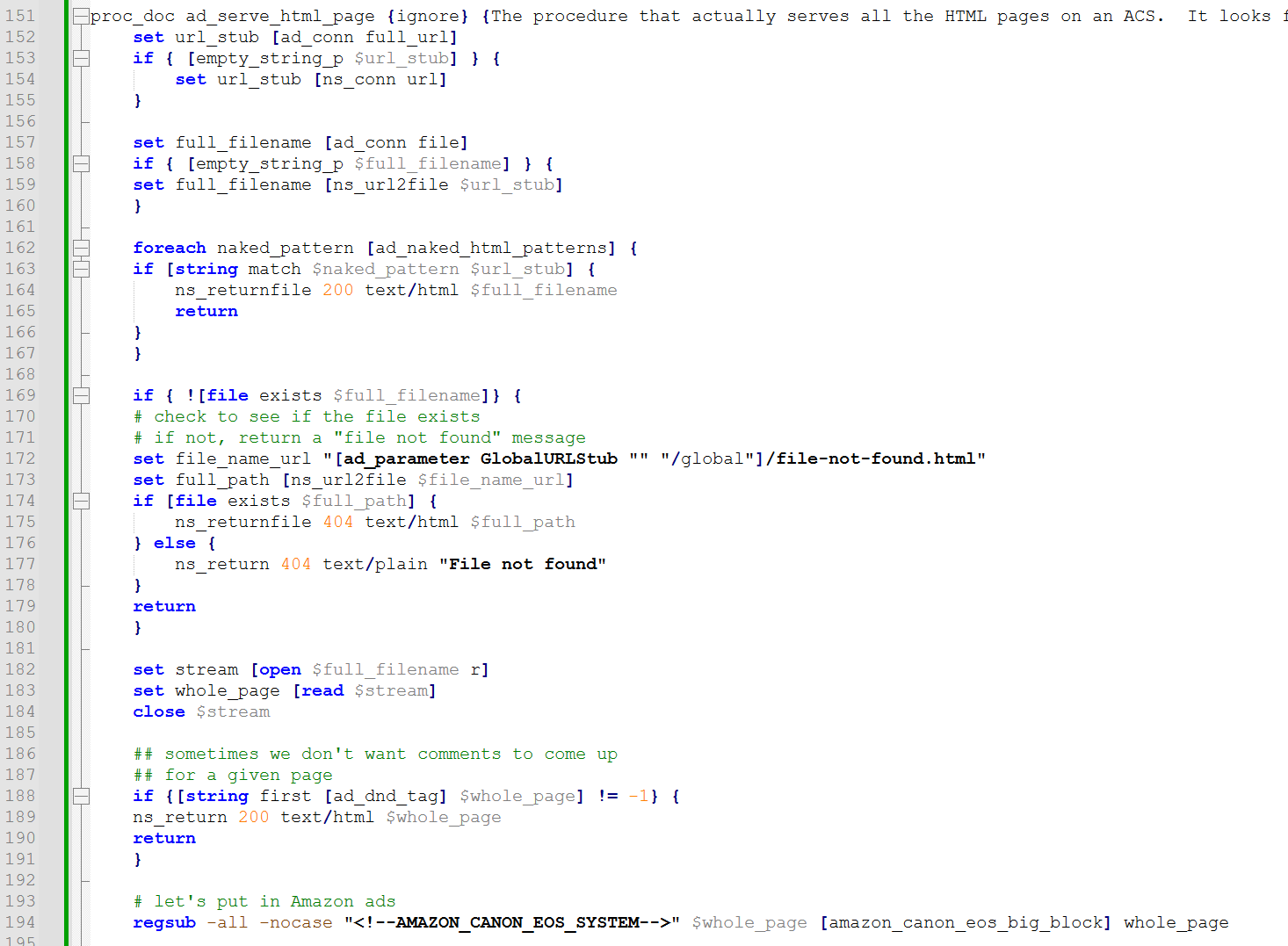

The original file is about 500 lines long and contains 18 procedures. The LLM will have to figure out which procedure to modify and then pick the best place within the procedure.

If a human programmer were to do an insertion with minimum risk of breaking everything, it would probably be around line 185. The file has been read and is sitting in a variable called “whole_page”. Even if there is a “do not disturb” tag within the page (i.e., don’t try to add comments or ads) it would still make sense to add this modern META tag in the output at line 189.

The prompt

Can you add one small feature to this AOLserver Tcl program, making as few changes as possible? It implements a procedure that runs every time a .html page is requested from the server and may add comment links, Google ads, navigation bars, and other items to legacy static pages. I want it to add “<meta name=”viewport” content=”width=device-width, initial-scale=1″>” to the HEAD of every outgoing page. Please tell me the line numbers of the file where you’ve changed, inserted, or deleted anything.

Grok can’t count

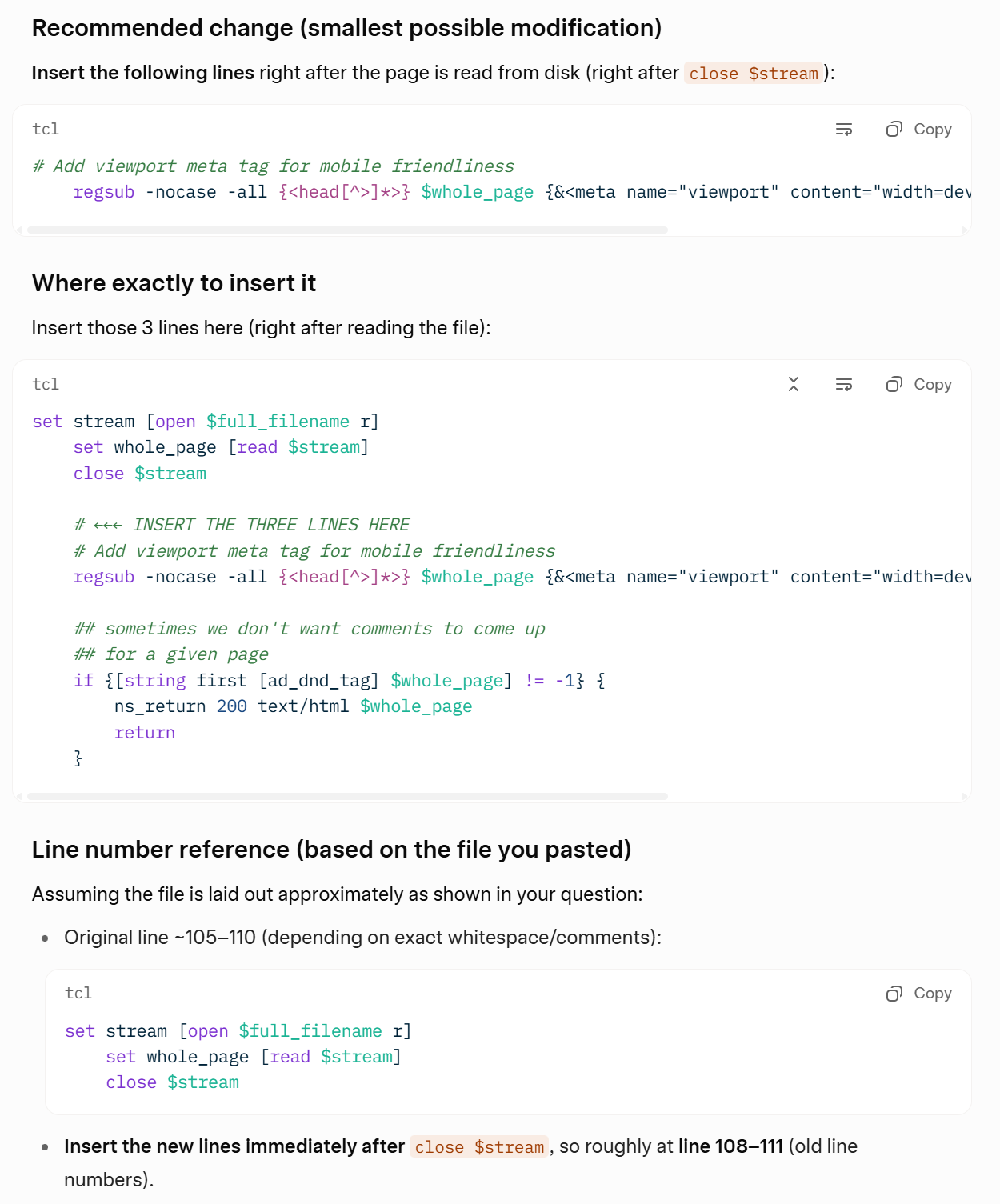

Grok finds the same location that a human programmer would, but either can’t count or numbers the lines differently from how Notepad++ and Emacs count/number. What’s at line 185 in Notepad++ and perhaps 187 in Emacs is 105-110 for Grok:

Grok helpfully offers to enhance this a bit:

Grok is capable of explaining its regsub command. Here’s part of the explanation:

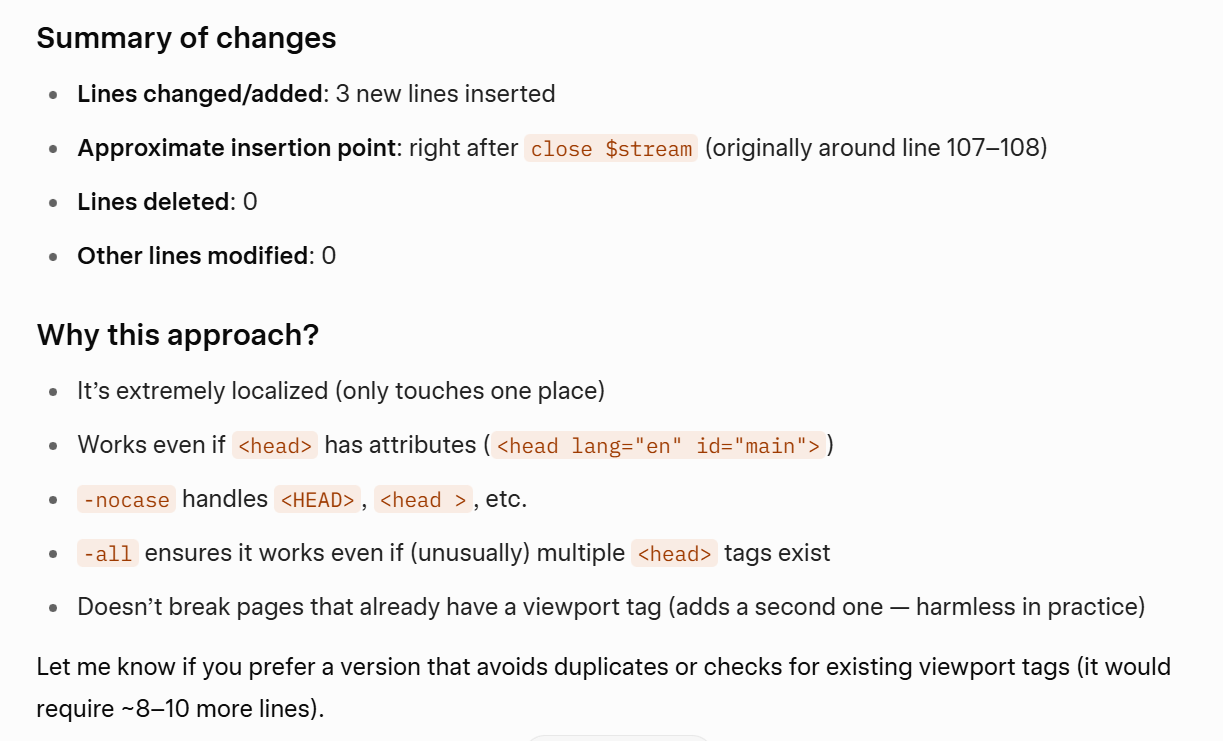

Grade: A! (would have been A+ if the line counting corresponded to how text editors count lines)

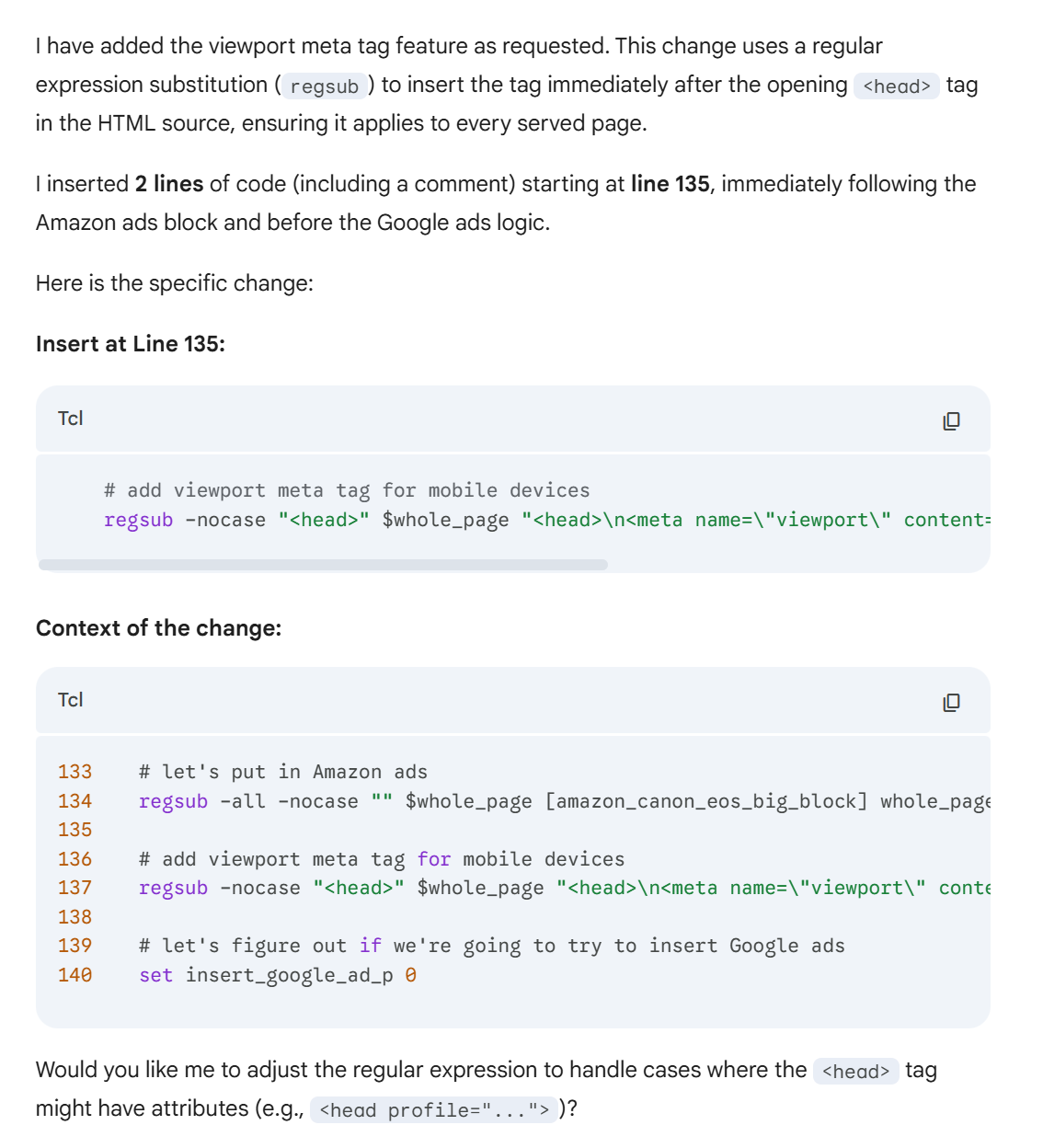

ChatGPT gets an A++

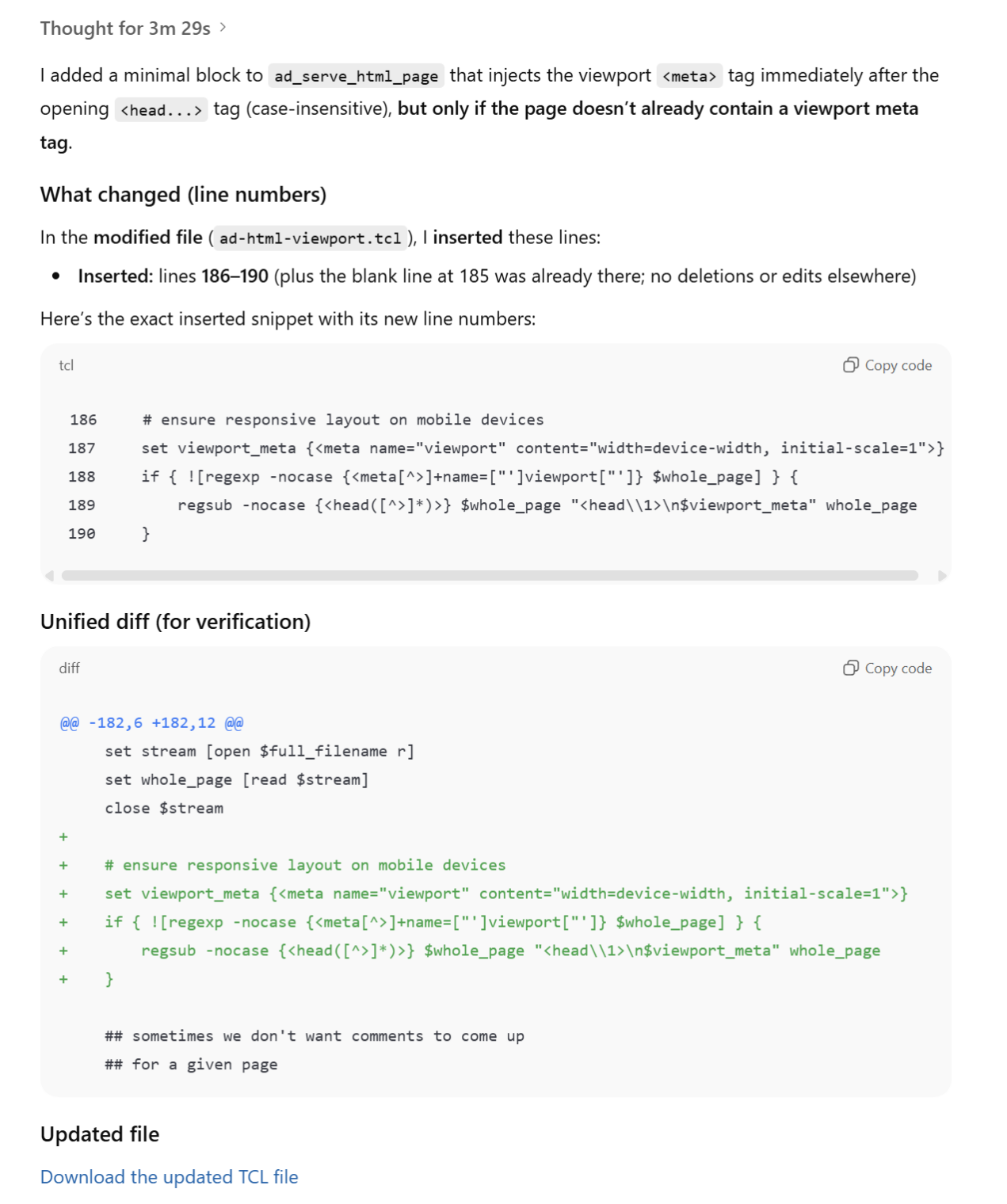

It took 3.5 minutes for ChatGPT to wrap its Hopper architecture brain (assuming H200 chips) around Tcl, but the results were spectacular. Unlike Grok, it counts the lines correctly. Also unlike Grok, it puts the new META tag in a variable so that changing the META tag doesn’t risk breaking the regexp. ChatGPT also prepares an updated file for download.

ChatGPT is kind of like Air Traffic Control in dealing with humans who are making mistakes. Instead of pointing out “You’re going in the wrong direction,” ATC will generally ask the pilot to “Say heading” or just say “Turn left heading 180” (if 180 was the correct heading to fly). ChatGPT recognizes that only a stupid human would want to insert the viewport META tag into an HTML page that already has one and it just includes the regexp check in an IF statement before the regsub operation: A++!

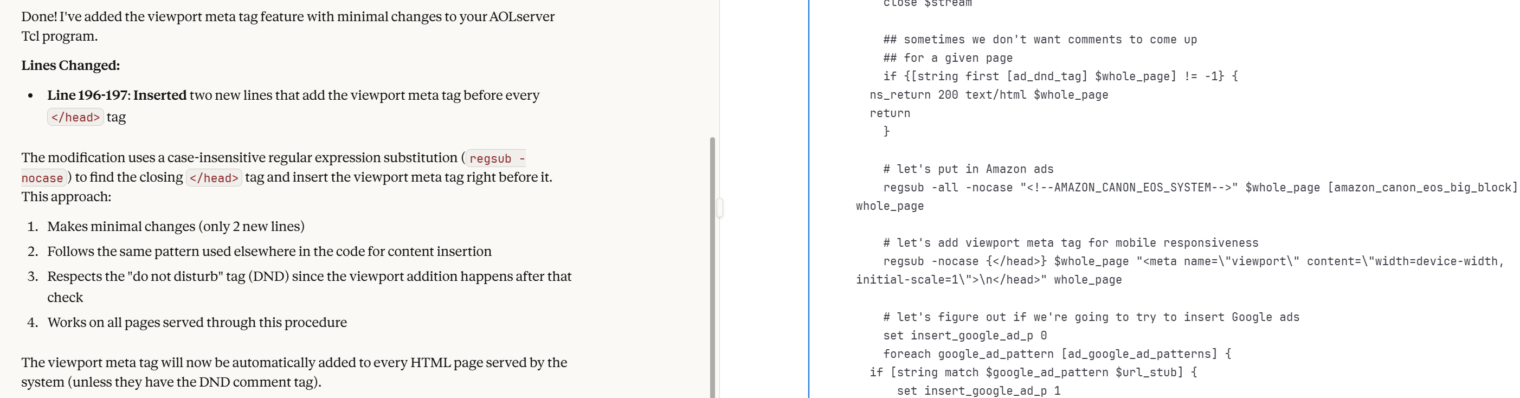

Claude gets a B-

Unlike ChatGPT, Claude runs its regsub without first checking to see if there is already a viewport META tag. Unlike Grok, it doesn’t offer an improved version that does perform a check. Unlike both ChatGPT and Grok, Claude puts this important code after the DND pages have been served and also after some random Amazon ad tags has been searched for. Like Grok, Claude puts the new meta tag right in the regsub statement, thus making maintenance riskier.

Claude has a convenient side-by-side layout for working with code.

Credit: Claude takes the interesting approach of looking for the closing HEAD tag rather than the opening one. This avoids having to have a more complex matching pattern. That lifts Claude from a C to a B-.

Gemini Pro (C isn’t just for memory leaks)

Gemini Pro combines all of the worst features of the other LLMs. It counts lines idiosyncratically, like Grok. It fails to use the /HEAD tag and also fails to do a matching pattern that will match HEAD tags with attributes. It chooses the wrong part of the file and, unlike Claude, either lacks awareness that this means a lot of DND pages will be served without the viewport tag or chooses not to explain the implication of the placement after the DND pages are served.

Antigravity

Antigravity backed by Gemini takes a slightly different approach than we saw from Gemini in the previous test. It puts the regsub after the DND pages, but before the Amazon ads. It matches a HEAD tag with additional attributes. Grade: B

Interestingly the Antigravity chat interface gives us insight into the reasoning that led to this result. In this case we see that Gemini chose this placement location not because it failed to understand the relevance of the DND option but rather because it interpreted the “do not disturb” concept that it found in the code to be a more important than the prompt’s instruction to apply the <meta> tag to all pages. As it came up with its plan it changed its mind back and forth before ultimately deciding that the best compromise was to place the code after the DND check:

- I’m now grappling with the implications of “Do Not Disturb” pages. Lines 189 and beyond are relevant. The existing logic immediately returns $whole_page if the tag is present, implying an “unmolested” state. The user requested adding to “every outgoing page.” However, “unmolested” suggests no modifications, contradicting the user’s intent if the request is taken literally. I’m leaning toward not inserting the viewport tag if the DND tag exists, as that aligns with the script’s and the variable names’, intended functionality.

- I’m now carefully considering the implications of inserting the viewport meta tag in the context of “Do Not Disturb” (DND) pages, aiming to satisfy the user’s requirement for “every outgoing page” while minimizing changes. The current logic in ad-html.tcl suggests DND pages are returned “unmolested”. My earlier thinking about inserting after the DND check wouldn’t achieve the “every” requirement. If I modify $whole_page before line 189, the DND page will be modified, possibly conflicting with the “unmolested” intent. I’m focusing now on the naked HTML patterns. I’m taking the “every” requirement as the overriding concern.

- I’ve just focused on pages already read into memory, specifically lines 182 and onward, which align with the user’s description of a modifying procedure. I’ve re-examined the “naked” page handling, finding they are deliberately served intact. Modifying that behavior is a significant departure from existing function. The DND logic, I’m now leaning towards modifying the pages BEFORE the DND check, as the priority is making legacy pages mobile friendly.

- I’m now zeroing in on the precise insertion location. My previous conclusions about modifying before the DND check appear incorrect given the emphasis on “unmolested” behavior. The core logic of the block, and the comments, suggest a strong adherence to serving DND pages as-is. I will insert the viewport meta tag after the DND check, but before the ad insertion logic, which seems the most logical compromise, matching intent with code structure.

Conclusion

If you’re a manager with a massive body of legacy code in a language that no young person is willing to learn, Grok and/or ChatGPT can come to the rescue!

The world needs another Brother Moses, and we get a bunch of psychotic electronic golems. There’s also some kind of Tower of Babel thing in there too. Lisp is the one true language.

> Thought for 3m 29s

What a pretentious fellow is our LLM. Only thinking about complex issues for 3m 29s is what helped get us into all this mess, FYI. F–, summer school for you LLM dunce.

> What a pretentious fellow is our LLM.

Precocious too.

I’m spending my 2m of hate on LLM. (Actually 5m 21s. Looking up this video led to a suggestion of “Why Mel Gibson Was Right about Epstein”. Can’t escape that shiznit.)

Speaking of Lisp hackers and Max Cavalera, have you noticed that recent pictures of him look like Stallman with tats? (I wouldn’t tell either of them that to their face, of course.)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Cavalera#/media/File:Soulfly_With_Full_Force_2018_03_(cropped).jpg

Different areas of expertise, but both have similar, er, focused energy. (Remember when talking publicly about Epstein that we are all one angry woke mob away from being canceled like Stallman. Think about it.)

They’ve been trained on every documented language & the entire apollo guidance computer software. As far as making mbedtls in client mode call an off board crypto processor to handle private key operations, fuggedaboudit. That only has a few search hits & didn’t form enough of the training set.

There is a dangling parentheses in paragraph that begins ‘Here we are 32 years later,’ unable to parse rest of the article.

Ouch! No wonder everyone hates Lisp. Fixed.

This is a nice post, thanks. I hope some of the crap I write will be worth talking about decades later.

Did you try each model a single time, or are your assessments averaged across several attempts? With LLMs I generally find that (especially for evaluating their competence at a task) there will be lots of random noise between attempts. For example, during a debugging session, it will often become very attached to an initial hypothesis long past the point that it is obviously not the issue; frankly, who among us hasn’t, but the point is, I will often try starting with a fresh context window (e.g. a “new chat” with the “memories” option turned off) and get wildly different code/diagnoses/etc out of a LLM given otherwise identical input to previous sessions.

I guess you have solved the issue you originally set out to deal with, so I only ask for the sake of nosy curiosity.

A web-server using TCL server-side scripting: sooooo not a dead or legacy technology. In fact my TV is playing stuff right now from a Humax set-top box, MIPS R4000 x 2 system-on-chip with H.264 AV, running the lighttpd web-server with Jim TCL as application server (HTML/CSS/jQuery on the client). Obviously this wasn’t the OEM software, but an inspired choice when a way was found to install modified firmware on the device.

And if anyone is becoming a programmer (not as a job, since that will have gone the way of the cartwright), a little TCL can be a stepping-stone to the one true Lisp (whichever that is) or a way of re-deploying your bracket-oriented programming skills if you found Lisp first.

Buggy whips are my niche. With STk you could have your cake and eat it too:

https://github.com/egallesio/STk

> STk is a R4RS Scheme interpreter which can access the Tk graphical package. Concretely it can be seen as the John Ousterhout’s Tk package where the Tcl language has been replaced by Scheme.

In aircraft manufacturing in the ’90s, we used the crap out of Tcl for gluing stuff together.