Gemini and Antigravity fixed the Bill Gates Personal Wealth Clock

Bill Gates has been in the news lately.

“Melinda French Gates says latest allegations about Bill Gates’ antics with Epstein dredge up ‘very painful’ memories” (New York Post):

Melinda French Gates said that new details of ex-husband Bill Gates’ alleged antics with Jeffrey Epstein dredge up “very painful times” from their 27-year marriage — and have left her “so happy to be away from all the muck that was there.” … “It’s personally hard whenever those details come up, right? Because it brings back memories of some very, very painful times in my marriage,” she told NPR’s “Wild Card” podcast on Tuesday.

“I’m able to take my own sadness and look at those young girls and say, ‘My God, how did that happen to those girls?’” she said.

There’s a video with Melinda Gates where she smiles as she talks about the “sadness”. Keep in mind that, via a personal relationship with the boss, she made more money than the entire team of software engineers who built Microsoft Windows. Perhaps this has occasioned some “sadness” among those who worked 100 hours per week?

(Also, she implies that Bill Gates was having sex with “young girls” (a “young girl” would be 10? 12?). Is there any evidence of that in the Epstein files? Epstein pleaded guilty to partying with paid women as young as 16 back in 2008, but is there anything definitive in these files or elsewhere to suggest that, post-2008, “young girls” were having sex in exchange for cash or other inducements with Bill Gates or any other Epstein friend? A lot of Americans seem to be energetic when it comes to condemning Jeffrey Epstein and his circle. They say that they’re passionate about “the victims”, but Epstein died in 2019 and any “victims” are adults today. There are teenage prostitutes working right now in various states and countries. The folks who energetically condemn Jeffrey Epstein don’t try to do anything about current teenage prostitutes. If they live in Maskachusetts, for example, they don’t lobby to raise the age of consent from 16 to 18 or 21.)

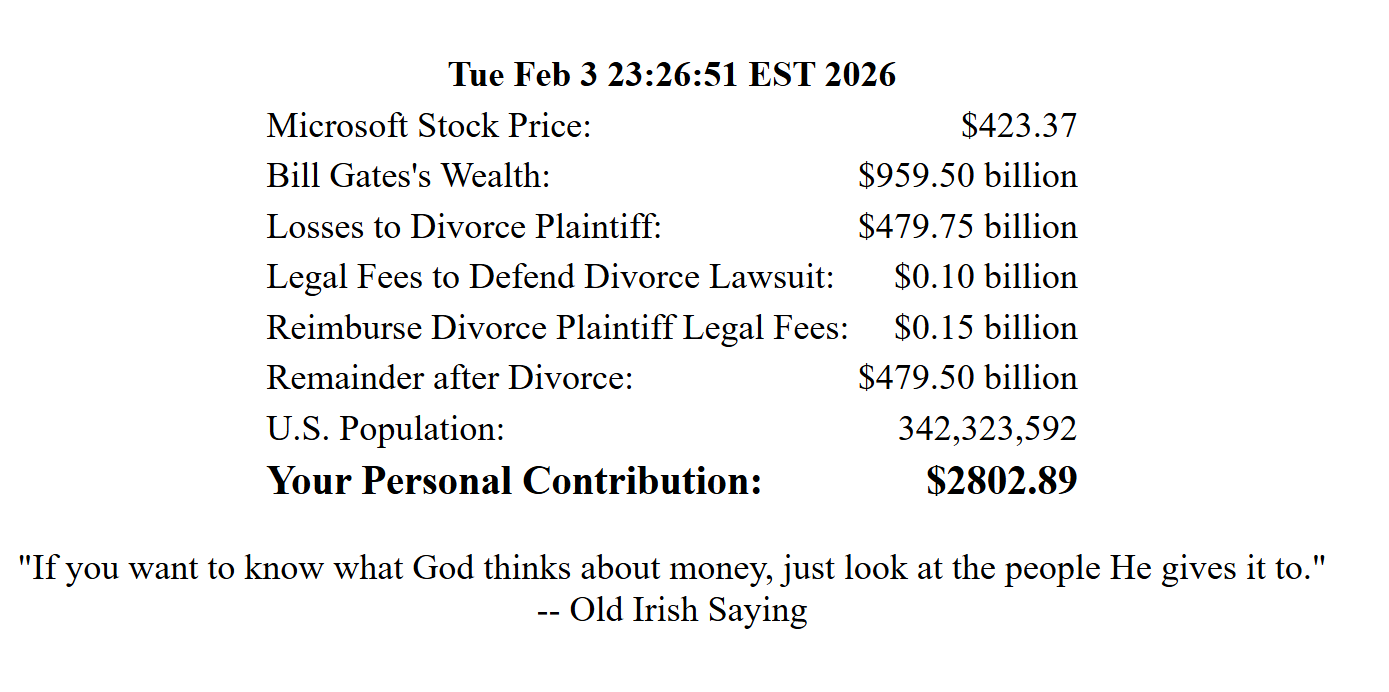

Thirty-one years ago, as an envious impoverished graduate student, I developed the Bill Gates Personal Wealth Clock:

The clock had broken because the U.S. Census Bureau put in additional barriers to scraping their popclock and the sites for getting stock quotes kept changing.

I fed Antigravity on a copy of the entire tree behind my web site and, incredibly, it/Gemini was able to answer questions about AOLserver configuration, Tcl API code, relational database structure, etc. It suggested fixes to the software that actually worked, e.g.,

set population_html [exec curl -s -L \

-H "User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/120.0.0.0 Safari/537.36" \

-H "Accept: application/json, text/javascript, */*; q=0.01" \

-H "Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9" \

-H "Referer: https://www.census.gov/popclock/" \

-H "X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest" \

"https://www.census.gov/popclock/data/population.php/us"]

for scraping the Census web site.

I wonder if the page is conceptually broken. For a couple of decades, the page seemed to track reasonably well with (1) reports of Bill Gates’s personal stash, and (2) reports of total assets in the Gates Foundation (I considered them both to be forms of wealth for him since he controlled the foundation).

Right now, though, the grand total of $960 billion seems to be off the reservation (and we don’t need Elizabeth Warren to tell us how bad that is). I’m wondering if the explanation is Microsoft issuing shares like crazy to employees, thus diluting Bill Gates’s ownership percentage. The Google says that Gates is worth about $100 billion personally and the Gates Foundation total assets is about the same. That would put his total post-divorce wealth at $200 billion, not $500 billion. The Gates Foundation has supposedly paid out (“squandered”?) roughly $83 billion (mostly money extracted from American computer users and handed over to Africans without the U.S. Treasury ever collected a dime of capital gains tax). That still gets us to only about $300 billion. How did the discrepancy arise? Could it be that Gates was diversifying and paying capital gains taxes over the years, thus getting the mediocre returns of the S&P 500 instead of the Mag 7 returns of Microsoft? Or did he do what all of our other noble billionaires do and borrow against his appreciated stock to fund lifestyle? Google AI says that “he has borrowed hundreds of millions against his assets … [and] Despite using tax-efficient strategies, Gates has publicly advocated for higher capital gains taxes for the wealthy.”

Related (simple non-RDBMS web apps from the same era):

- The Game, a dating practice app

- Aid to Evaluating Your Accomplishments