NBAA 2015 wrap-up report

Here’s a wrap-up of items from the National Business Aviation Association 2015 convention in Las Vegas…

The convention opened with a presentation on how great business aviation is. The most compelling speaker was Dierks Bentley, who has been working his way up from the Cirrus to a light jet while simultaneously singing country songs about old pickup trucks. He introduced himself with a video in case anyone in audience “sadly doesn’t listen to country music.” How did he get to where he is? He talked about working harder than anyone else, which included dropping personal plans to “play any gig”. He currently tours 150 days per year and using a personal airplane lets him spend extra nights at home, drop the kids at school, go to the gym, etc. This does raise the question of carbon footprint for the music industry. One might have expected the footprint to go down with the improvement in ease of electronic access to music. I can listen to Bentley right now on Rhapsody so why does he need to come to Boston? And if he does come to Boston, now it will be in a point-to-point jet ride from Nashville, rather than on a diesel-powered bus that covers 20 cities for the same amount of fuel.

And with that, the event opened with a convention center full of booths and a static display area at the nearby Henderson, Nevada airport.

The crazy capable, actually certified, incredibly small SJ30 had flown in. Six are out there flying, including one owned by Morgan Freeman. You can go from Las Vegas to Hawaii and enjoy sea level cabin pressure at 41,000′ or get over powerful storms at 49,000′. The interior is only about half the size of a comparably priced airplane.

Gulfstream had every model on static display. It was theoretically possible to tour a G650 in the same sense that it is theoretically possible to go to the hippest club in Los Angeles. People were in line, but it wasn’t the real line. Salespeople and their VIP clients would show up every 10 minutes and jump the queue so that the visible line almost never moved.

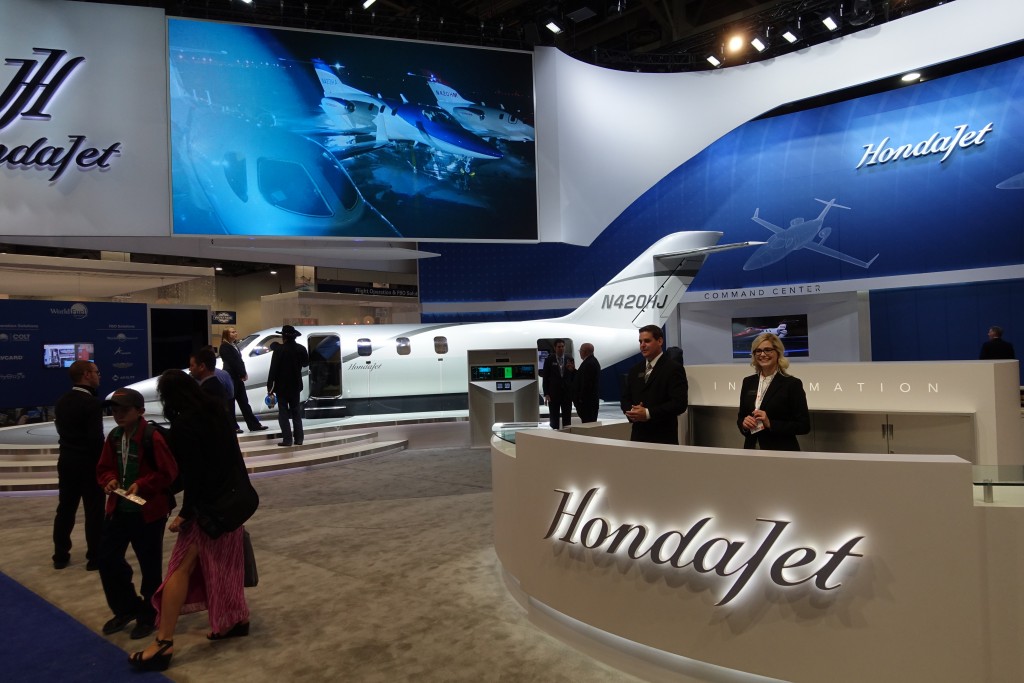

Honda is finally getting their little jet out the door, 12 years after the first flight and about five years later than planned. Unfortunately it is a terrible fit for the “go big or go home” world that general aviation has become. There are only about 100 orders for the plane, according to one of their salespeople at the show. If they want to make money they will need to stretch this into something the size of a Phenom 300.

How about getting some car-like features in an airplane? A read-out of tire pressure in the cockpit is apparently too much to hope for, but SmartStem was there with a handheld tire pressure reader that talks to a sensor inside each tire. What does it cost? About the same as a reliable used car.

Speaking of car-like features, how about some system integration and self-management for subsystems? Above are some photos of Bell’s certified-in-2008 429 helicopter. This is a single-pilot IFR helicopter. I.e., you’re flying this helicopter in the clouds and something goes wrong. This will almost certainly result in the autopilot disconnecting itself. Now you must have your hands on the controls but you’re also supposed to be running checklists and flipping all of these switches? More importantly, what happens to all of this horizontally-mounted switches when you spill your drink? And where do you put the iPad? (And what if you want to see these switches in the event of smoke in the cockpit? You would need something like EVAS, shown at NBAA. Another good reason for automatic systems to make triage decisions when stuff fails.)

Speaking of iPads… the major avionics manufacturers gathered for a seminar to talk about the glorious future. The high-level message was that certification times are stretching out due to regulatory authorities being busy with drones and generally becoming more cautious. This results in new systems, such as CPDLC, being “obsolete before they are launched.” By the time the world’s aircraft are fully complaint with the U.S. ADS-B mandates and the European FANS mandates, it will be possible to establish 100 Mbits/second Internet via satellite to all aircraft, at which point nobody would have wanted all of this primitive stuff. The avionics world is now working on establishing a barrier between the certified stuff in the panel and the innovative stuff on the iPad. They’ve pretty much given up on significant innovation for software that has to be FAA-certified and thus an increasing amount of a pilot’s attention will be directed toward non-certified apps on a tablet (Apple is the dominant choice of tablet hardware/software).

Regulatory compliance was a huge theme in the conference (the sign above was about 5′ tall, celebrating a booth owner’s capabilities). A tutorial session on “Emerging Regulations” was scheduled for 3 hours, twice as long as a session teaching people how to fly their Gulfstreams to China for the first time. About as many vendors showed up whose job was somehow to smooth out the path through regulation as showed up to present an innovative product.

Las Vegas is always a good window into the future of America. The monorail was designed to be run without drivers, but they still employ a lot of humans because they can’t manage the security risks without guards on platforms. Passengers are bombarded with loud radio-style advertisements in between every stop. The city hasn’t quite recovered from condo fever. Despite there being at least six conventions in town I was able to rent a magnificent one-bedroom apartment (balcony, master bathroom the size of a Cambridge studio apartment and containing enough marble to entomb a Communist leader, Sub-zero fridge, etc.) next to the MGM Grand for $200/night. As noted in the photo above, a lot of folks in the building can be special and have a “penthouse”. They had put a huge amount of effort into making sure that a wide selection of TV channels was available everywhere, but hadn’t been able to handle the challenge of providing a fast or reliable WiFi network, however.

Was there an intersection between the gambling-drinking-sex side of Las Vegas and NBAA? I didn’t see booths stuffed with showgirls or jet salespeople offering to hire escorts (Sports Illustrated covers this world in a unique way). I had dinner with the staff of a jet charter operator. The younger guys all went off to the Crazy Horse gentleman’s club at 11 pm while the owner, his wife, and I decided that it was time for us to collapse.

I had a “Press” badge and people asked what I wrote about. If I included comparative family law among the states in the list, there was about a 30-percent chance that the person would respond with a story or comment. Some of the respondents were women whose partner was being tapped for child support: “I refer to her as ‘the Parasite’, which used to upset my stepdaughter but there is just no other word that works.”; “Well, we hate her but what can we do about it? It is like having cancer that never quite kills you.” Most of the respondents were men, the dominant demographic at the show. About a third had been defendants in lawsuits related to out-of-wedlock births, e.g., following a casual encounter. A third had been divorce lawsuit defendants. A third had been observers of a friend or relative being targeted, e.g., in an abortion retail transaction. Here were some representative comments: “It drove me crazy until I realized that there was nothing that I could do for my son. The money that I had tried to invest in his college education went to pay the lawyers. The time that I had tried to invest in him was blocked by court order. The money that I would have invested in him from my income went to pay for my ex-wife’s vacations with girlfriends and boyfriends. Maybe 10 percent of the child support checks trickled down to my son. When I gave up and stopped trying to invest, that’s when I was no longer in conflict with my ex-wife or the family court system.”; “Wherever jets are parked there will be pussy workers.”; “Eventually I began to admire her for being clever enough to earn money without going to work.”; “Putting 1000 miles between me and the state where I lost everything was the only good decision I can remember making. I was a lot happier once I stopped paying taxes to support the judge who took my kids away. The every-other-weekend schedule was ridiculous and you’re fooling yourself if you think you’re still a parent at that point.”; “The aviation industry and the pussy industry are symbiotic.”; [from a German] “If you open a German tabloid in any typical week you’ll read about a woman who divorced her rich husband and was so upset about the end of the marriage that she had to move with the kids to New York or Los Angeles. Really it is about trying to get a U.S. court to take over and order child support at U.S. rates.” (maximum child support revenue in Germany is much less than what can be earned from working a W2-style job); [from a European immigrant to the U.S.] “I tell the younger guys in our operation that, unless they’ve had a vasectomy, all sex in the U.S. can be commercial sex. The only question is whether they’ll pay from their wallet the same night or from their bank account over the next 18 years.”

Do you remember the 1970s fondly? If so, AdaCore was there promoting its Ada programming tools to avionics companies that need something more reliable than typical JavaScript. Was it supersonic passenger travel that you remember more fondly than Ada? It’s coming back for you and seven friends: the $120 million Aerion (Bernie Sanders nose art optional). Flexjet has ordered 20 of these, hoping to accept delivery in 2023.

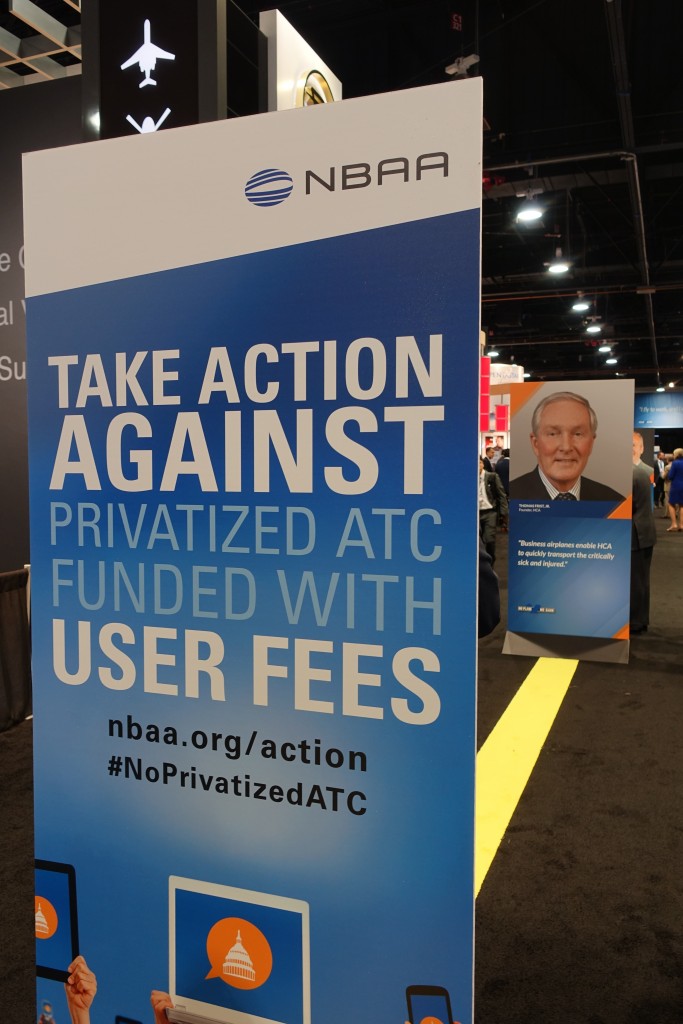

Signs throughout the conference exhorted participants to fight proposals to turn over the government-run air traffic control system to a private monopoly that would then extract fees for for each flight (the current system is funded by taxes on aviation fuel and on airline tickets). Whenever Americans try to do something like this it does, a combination of cronyism, complacency, and incompetence seems to result in a worst-of-all-possible-worlds outcome in terms of price and service (see also the U.S. health care system!). Evidence of what a debacle might ensue is provided by the ADS-B system. The system has been in development for decades and has cost taxpayers more than $6.5 billion (AOPA). The U.S. DOT shows about 200,000 aircraft registered in the U.S., so that’s $32,500 per aircraft for a system that won’t be fully operational until 2025. Aircraft owners will have to pay between $10,000 and $400,000 per aircraft to comply with ADS-B requirements, so let’s call it a median of $50,000 per aircraft in tax and private funds as setup costs and an unknown amount of annual operating costs for all of the ground stations. What has the incredibly slow-moving private avionics industry managed to do in the meantime? Satellite Internet boxes for airplanes are now available for about $20,000 for speeds of 100 kbps. How fast is ADS-B by comparison? It doesn’t seem to have enough bandwidth to transmit weather reports for all U.S. airports, the way that the 15-year-old XM-based weather system can. The FAA researchers who presented a “weather in the cockpit” seminar couldn’t answer the question about the bandwidth but explained that their colleagues on the show floor probably could. Why can’t it do what XM did 15 years ago? “That program was awarded to a contractor and they just do the bare minimum of what the contract requires in terms of running ground

Full post, including comments