A friend’s daughter is doing some research on divorce, custody, and child support litigation. Today I took her over to the Middlesex County Probate and Family Court in East Cambridge so that she could see what was happening. It turned out that we were there on “Department of Revenue (DOR) Day” where the Commonwealth itself sues deadbeat dads on behalf of mothers who had previously been successful custody and child support plaintiffs but hadn’t received the amounts ordered. This saves the moms from having to retain and pay attorneys; the lawsuits are handled by taxpayer-funded attorneys.

The first guy to appear was, not to put too fine a point on it, a genuine bum. He appeared to be in his 50s, with graying hair, shabby clothing, and a physically disabled posture that might have been due to the fact that he was in handcuffs and ankle chains. He had last worked at a biotech company in Massachusetts back in 2010, but it wasn’t clear in what role. He paid child support to a trim, well-dressed plaintiff while he was working and continued to pay child support while collecting unemployment. When that ran out and he still hadn’t found a job he fled to Idaho and worked as a caretaker in exchange for a free place to sleep. “How did you eat?” asked the judge. “Food stamps,” he replied. During this period he called the three children (current ages: 17, 20, and 22 (in Massachusetts it is possible to collect child support for children until they turn 23)) but didn’t send any money to their mother. “Where are you living now?” With his mom in Billerica, it turned out. The DOR attorney railed against this loser who had “abandoned his responsibilities” and “refused to work” and asked that he be imprisoned for 60 days and fined $5000 on top of the $41,000 that he owed his former plaintiff and the money that he continued to owe for the two adults and one minor child. Throughout the proceeding the chained deadbeat was surrounded by five armed sheriffs, each of whom was probably costing the taxpayer $250,000 per year (salary, benefits, pension, etc.). The judge asked him a few questions about the efforts he was making to get a job, e.g., “How many resumes have you sent out?” then lectured him on how it was obvious that he could and should get a job. She ordered that he be imprisoned for 30 days and fined $2000. The deadbeat did not seem surprised by or object to this. The five sheriffs added some additional shackles to his wrists and ankles, then escorted him out.

The second guy was apparently at an earlier stage of the process because he was not in chains. His plaintiff did not appear because, she had written to say, driving made her “anxious”. The subject of the child support obligation was an adult (over 18 but younger than 23). This child lived full time with the father, but the plaintiff mother still had a child support order in place from when the child lived with her at least part-time. It seemed that a second woman had been unwise enough to select this man as the father of her children and he had two preteen girls living at home with him and, due to his lack of employment, there was not enough money to pay the mother of the adult child as well as put food on the table for the adult child (living with him) and the two minor girls. He did not ask for the “adult-child” support to be eliminated going forward, on the grounds that the adult lived with him, but only for it to be reduced and for the judge to order a gradual payment plan for the arrears (more than $10,000). He received a stern lecture on how it should be straightforward for him to find a job and then was allowed to leave without handcuffs.

Based on what we heard and saw, for these guys to get a job, America’s employers would have to

- hire all 9.5 million currently unemployed people

- entice another 6 percent of the population back into the workforce so that the labor force participation rate was up towards a historic high

- fund $1 trillion in unsuccessful robotics research

- be under the influence of both drugs and alcohol on the day that these two prize specimens came in for their interviews

The human tragedy aspect of the cases was first and foremost in my mind but after we were out of the courthouse, I thought “Hey, wait a minute. If you are a long-term unemployed person one government agency will tell you that this situation could not have been avoided, it is not your fault in any way, and here are some tax dollars so that you can make ends meet. But if the same long-term unemployed person owes child support, even he is at the extreme end of the spectrum of demonstrably unemployable, employees of the same government but at a different agency will tell him that he could easily get off his ass and earn enough money to support himself plus have enough left over to pay $41,000, after taxes, to the person who sued him two decades ago.”

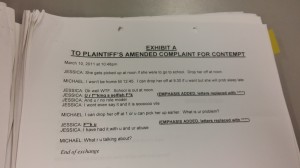

[Separately, we went to the records department and sampled some cases. Here are two parents in the midst of a divorce lawsuit coordinating the exchange of a three-year-old via text message:

(background: Ivy League graduate wife sued husband after four years of marriage, ultimately winning a free house, roughly half of her attorney’s fees (despite a prenuptial agreement that said each side would pay his or her own), 100% of the child’s expenses, including a full-time nanny, paid by husband, $50,000 per year in taxable alimony, and nearly $94,000 per year in tax-free child support through the toddler’s 23rd birthday (the plaintiff would take care of said child, with the assistance of the nanny, for slightly more than half time))]

Related: Divorce in Denmark (the scenes that played out in front of us in Middlesex County probably would not have happened in Denmark because when a parent cannot pay the $2200/year minimum child support the government steps in to pay it without expecting to be paid back, a source of irritation to middle-class taxpayers; the text message exchange also might not have happened due to the fact that the maximum child support obtainable is about $8000 per year)

Full post, including comments and it has even better dynamic range than the D800. The ability to hold detail simultaneously in highlights and shadows is the main limitation of digital cameras (compared to film) and Canon continues to stagnate while Nikon and Sony pull ahead. Check out this comparison on DxOMark of Nikon, Sony, and Canon.