Folks here in Boston have been speculating about whether Amazon will choose to locate its second headquarters amidst our already-clogged roads, bringing 50,000 jobs and maybe 200,000 more cars (employee cars; family member cars; cars belonging to people in service businesses that will expand as a result of Amazon’s presence, etc.).

The most common response to this idea is wondering “how could it possibly work?” We are already short on housing. The streets are jammed from 7:00 am to 8:00 pm. The MBTA’s subway system is packed and the service is falling apart as the enterprise is buried in pension and health care expenses. Unless they build a 50-story campus that includes dormitories for all workers and their families, nobody can figure out where an Amazon headquarters could go that wouldn’t result in Mexico City-style traffic jams.

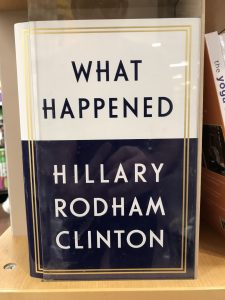

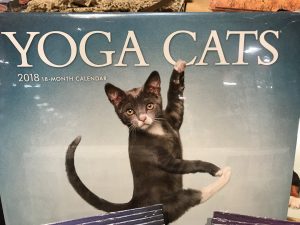

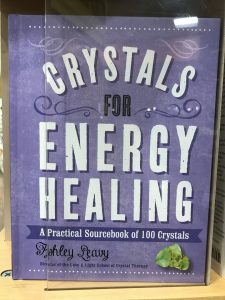

The Amazon HQ2 response from Boston is 218 pages. The proposal stresses that Amazon won’t be plagued with a lot of stupid native-born white people: “55% of Bostonians are Hispanic or non-White” and “29% of Boston’s population is foreign born”. I think this is basically a lie because they’re drawing an artificial line around the city itself rather than considering the metro area. On the other hand, when the authors wanted to find some nerds they draw the line regionally, e.g., “With 130,660 workers in computer and mathematical occupations, the Boston MSA has the 7th highest number … amongst 34 comparable metropolitan areas.” What do these computer nerds and math geniuses read? Here’s what the merchandisers at a Cambridge Whole Foods thought would sell:

The proposal makes clear that there is nowhere near enough housing, talking about “53,000 new units of housing by 2030.” In other words, the Amazon workers would take up 100 percent of the new housing that has been contemplated! Another lie is that “1 in 5 households in Boston are affordable, making Boston a national leader.” I think this is only true because the city gives away free housing to people who don’t work. None of the Amazon workers, by definition, would be eligible for these units. Market rents in Boston are brutal.

It promises “A perfect, shovel-ready site with a single owner.” Where will this be? Not really in Boston, as it turns out. It will be the old Suffolk Downs horse racing site, which is technically in East Boston, but is mostly attached to Revere, Massachusetts, a separate city. The proposal is reasonably honest about this, saying that “the Site is adjacent to and accessible to established neighborhoods of East Boston and Revere.” The proposal talks about MIT and Harvard graduates running around, but, unless you count trips to Logan Airport, most of these eggheads have never been to East Boston or Revere. Google says that this is a 50-minute trip from Harvard Square by T.

The Blue Line train is disclosed as having 71,000 passengers per day right now. How would it not collapse with tens of thousands of additional riders?

One group of folks that should be supporting this move are divorce litigators here in Massachusetts. The probability of a divorce lawsuit goes up dramatically as the potential profits from the lawsuit are increased. Washington State family law provides for much more limited profits than Massachusetts. A plaintiff cannot collect child support revenue in Washington after children turn 18; the cash continues to flow in Massachusetts until children turn 23. It is tough to get more than about $22,128 per year for a single child in Washington State; the plaintiff who can get custody of the same child in Massachusetts might win $100,000 per year (tax-free) in child support. A Massachusetts plaintiff is more likely to win “primary parent” status than in Washington State. Alimony lawsuits in Washington are also less lucrative, in general than in Massachusetts. In short, any Amazon employee who moves from Washington to Massachusetts and is the higher-earning spouse will face a higher statistical chance of being sued by his or her spouse. The Amazonian could try to protect himself or herself by settling in less-plaintiff-friendly New Hampshire, but the commute to Revere/East Boston would be brutal.

This would probably be the greatest thing that ever happened to JetBlue, which operates a major hub out of Logan, more or less adjacent to the proposed site. If you are confident that Boston will win this, buy stock in JetBlue!

Note that the proposal contains some even crazier ideas, e.g., that Amazon should try to spread itself among a whole bunch of different buildings in South Boston and downtown. Or maybe spread out across a couple dozen buildings in the South End, Back Bay (off the charts expensive), Roxbury, and some other unrelated areas.

My idea: Since Amazon can locate anywhere…. pick a happy place. Colorado always comes up in the top 5 happy states and always has cities in the top 5 or 10 (example). Boulder, Colorado would be awesome, obviously, but I don’t see how 50,000 new families could show up to the party. The area next to the big Denver airport is uncongested, on the other hand, and it will be convenient for Amazon employees to get anywhere on the planet from KDEN. Colorado family law doesn’t provide anywhere near the incentives to plaintiffs that Massachusetts does, so more of the Amazon workers will be able to keep their families intact. As a percentage of residents’ income, Colorado has a lower state and local tax burden than either Washington or Massachusetts. Denver has less traffic congestion overall than Boston (e.g., see TomTom data).

My backup idea: Vancouver! Amazon can gradually transform itself into a Canadian company and pay corporate taxes at Canadian rates (much lower). Vancouver is insanely packed, of course, but how about right next to the Boundary Bay Airport, a 35-minute drive to downtown Vancouver. The runway can handle an Airbus A320 or Boeing 737 to shuttle employees as necessary back and forth to Seattle (maybe less time than they currently spend commuting on Seattle’s own clogged freeway system).

Readers: What do you think? Does it make sense for Amazon to build a headquarters in a place whose transportation systems have already melted down? On the one hand, the meltdown of the transportation systems (car, bus, train, etc.) reflects the fact that people want to live in that place. On the other hand, since Amazon is one of the country’s best employers it would be able to draw people to wherever it settles.

[Question 2 for readers: How come progressive-minded government officials are bringing out the barrels of taxpayer cash to attract Amazon? Didn’t they read the New York Times expose about the abuse suffered by Amazon’s employees? If one believes the New York Times, why seek to bring that kind of abuse to one’s hometown?]

Full post, including comments