Per my usual, I didn’t watch Trump’s speech last night, but have peeked at the transcript. CNN establishes their neutrality in the first sentence:

Americans are reeling from the early weeks of Trump 2.0

The Google, informed by Oxford, says the definition of reeling is “lose one’s balance and stagger or lurch violently.” CNN reports as fact, in other words, that Trump has assaulted all Americans.

CNN compares Trump unfavorably to Franklin Delano Roosevelt:

Trump will always say he’s accomplished more than anyone. He’s got a way to go to catch presidents like FDR.

Maybe if Trump puts Japanese-Americans into concentration camps CNN will give him some respect?

Trump compares himself to slaveholder George Washington:

In fact, it has been stated by many that the first month of our presidency — it’s our presidency — is the most successful in the history of our nation. And what makes it even more impressive is that, do you know No. 2 is? George Washington. How about that? I don’t know about that list. But we’ll take it.

(see George Washington, Mules, and Donald Trump (2015): “real estate speculator-to-president is not an entirely new path”)

They heard my words and they chose not to come — much easier that way. In comparison, under Joe Biden, the worst president in American history, there were hundreds of thousands of illegal crossings a month, and virtually all of them, including murderers, drug dealers, gang members and people from mental institutions and insane asylums, were released into our country. Who would want to do that?

yields a “facts first” check from CNN:

From CNN’s Daniel Dale and Haley Britzky: There is no evidence for the president’s claim, which Trump’s own presidential campaign was unable to corroborate. (The campaign was unable to provide any evidence even for his narrower claim that South American countries in particular were emptying their mental health facilities to somehow dump patients upon the US.)

I’m not sure what about Trump’s statement CNN thinks is untrue. The federal government’s own statistics said that hundreds of thousands of noble migrants crossed the border in various months during the Biden-Harris administration. In any population of roughly 10 million (the total number of migrants during Biden-Harris rule) there will be at least some “murderers, drug dealers, gang members and people from mental institutions and insane asylums”.

I do love this one!

I could find a cure to the most devastating disease, a disease that would wipe out entire nations, or announce the answers to the greatest economy in history, or the stoppage of crime to the lowest levels ever recorded. And these people sitting right here will not clap, will not stand and certainly will not cheer for these astronomical achievements. They won’t do it no matter what. Five times I’ve been up here. It’s very sad, and it just shouldn’t be this way.

So Democrats sitting before me, for just this one night, why not join us in celebrating so many incredible wins for America. For the good of our nation, let’s work together, and let’s truly make America great again.

This is kind of funny:

We ordered all federal workers to return to the office. They will either show up for work in person or be removed from their job.

CNN fact check: More than half of federal workers were already working from the office full- or part-time when Trump took office

This reminds me of going to a California law office in 2024 and asking the receptionist how many people were coming in to work. She characterized the office as “packed” with perhaps 50 percent of people coming in on a given day (I saw only a handful of them). The post-coronapanic norm for desk jobs seems to be that only about half of people will show up and most of them will show up only part time.

Everyone who disagrees with me is a racist:

And two days ago, I signed an order making English the official language of the United States of America.

CNN: The English as a national language and Gulf of America efforts can be tied together with a very clear racial overtone.

(the majority of English speakers don’t live in the U.S., of course)

Just listen to some of the appalling waste we have already identified. $22 billion from HHS to provide free housing and cars for illegal aliens. $45 million for diversity, equity and inclusion scholarships in Burma. $40 million to improve the social and economic inclusion of sedentary migrants. Nobody knows what that is. $8 million to promote LGBTQI+ in the African nation of Lesotho, which nobody has ever heard of. $60 million for indigenous peoples and Afro Colombian empowerment in Central America — $60 million. $8 million for making mice transgender. This is real. $32 million for a left-wing propaganda operation in Moldova. $10 million for male circumcision in Mozambique. $20 million for the Arab Sesame Street in the Middle East. It’s a program — $20 million for a program. $1.9 billion to recently created decarbonization of homes committee headed up — and we know she’s involved — just at the last moment, the money was passed over — by a woman named Stacey Abrams. Have you ever heard of her?

CNN’s response is interesting. They aren’t able to say that Trump is wrong about any of the above except that they take issue with “$8 million for making mice transgender” (i.e., the $22 billion number at the beginning of the passage is apparently correct) [Update: Apparently there were some fact-checker-checkers and the government’s transgender mice project was real so CNN updated its criticism of Trump to say only that the $8 million number might not be right.]

Last year, a brilliant 22-year-old nursing student named Laken Riley — the best in her class, admired by everybody — went out for a jog on the campus of the University of Georgia. That morning, Laken was viciously attacked, assaulted, beaten, brutalized and horrifically murdered. Laken was stolen from us by a savage illegal alien gang member who was arrested while trespassing across Biden’s open southern border, and then sent loose into the United States under the heartless policies of that failed administration — it was indeed a failed administration. He had then been arrested and released in a Democrat run sanctuary city — a disaster — before ending the life of this beautiful young angel. With us this evening, are Laken’s beloved mother, Allyson, and her sister, Lauren.

CNN says that only Republicans are better off when violent criminals are detained:

Riley’s death was a major campaign issue for Republicans, and passing the Laken Riley Act, which requires certain migrants to be detained when accused of a crime, was a major victory for Trump and Republicans.

Democrats are better off, CNN reports as a fact (this is not an opinion section piece), when people like José Antonio Ibarra are not detained.

This seems kind of insane:

To boost our defense-industrial base, we are also going to resurrect the American shipbuilding industry, including commercial shipbuilding and military shipbuilding.

And for that purpose, I am announcing tonight that we will create a new office of shipbuilding in the White House and offer special tax incentives to bring this industry home to America, where it belongs. We used to make so many ships. We don’t make them anymore very much, but we’re going to make them very fast, very soon.

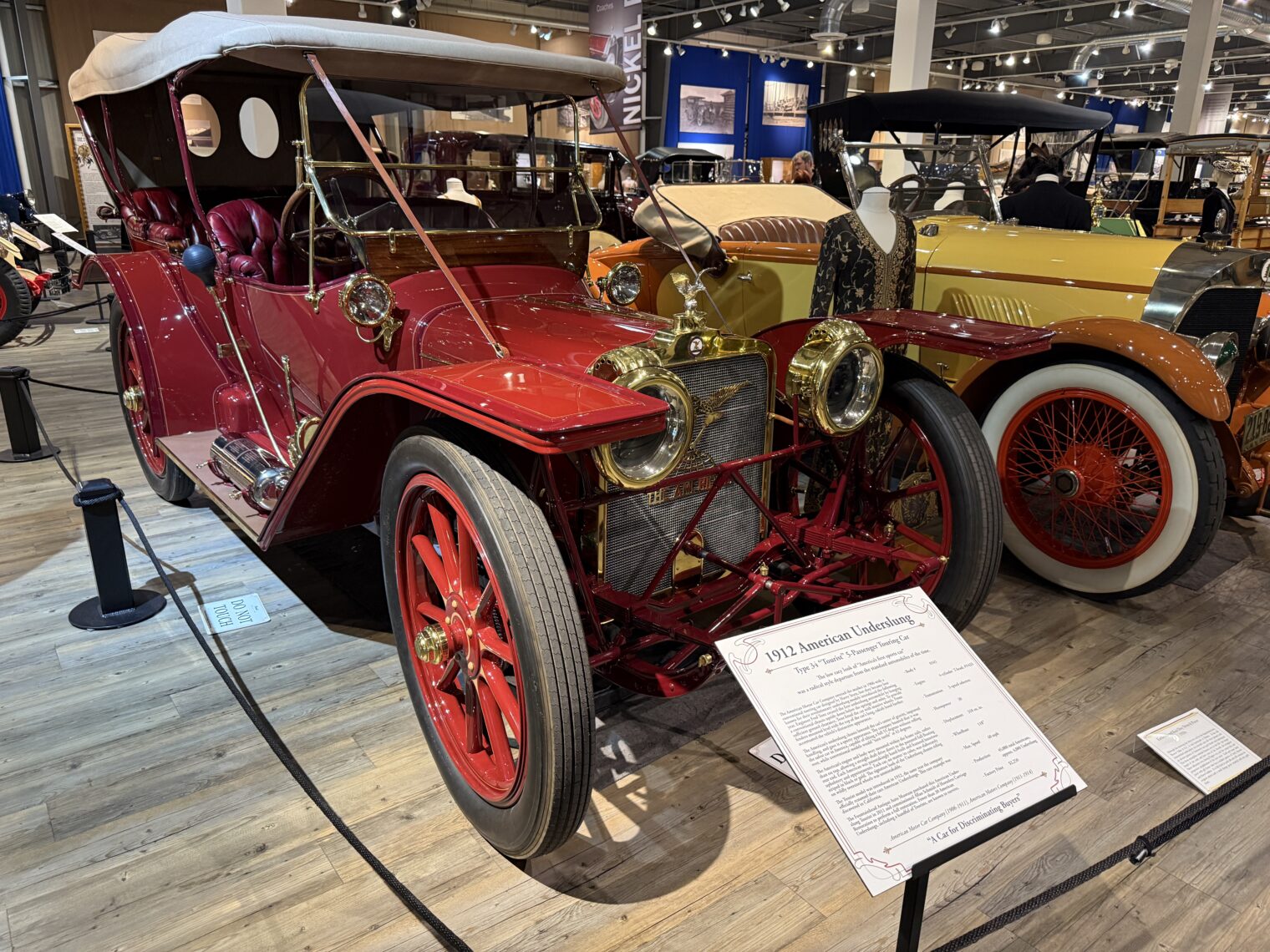

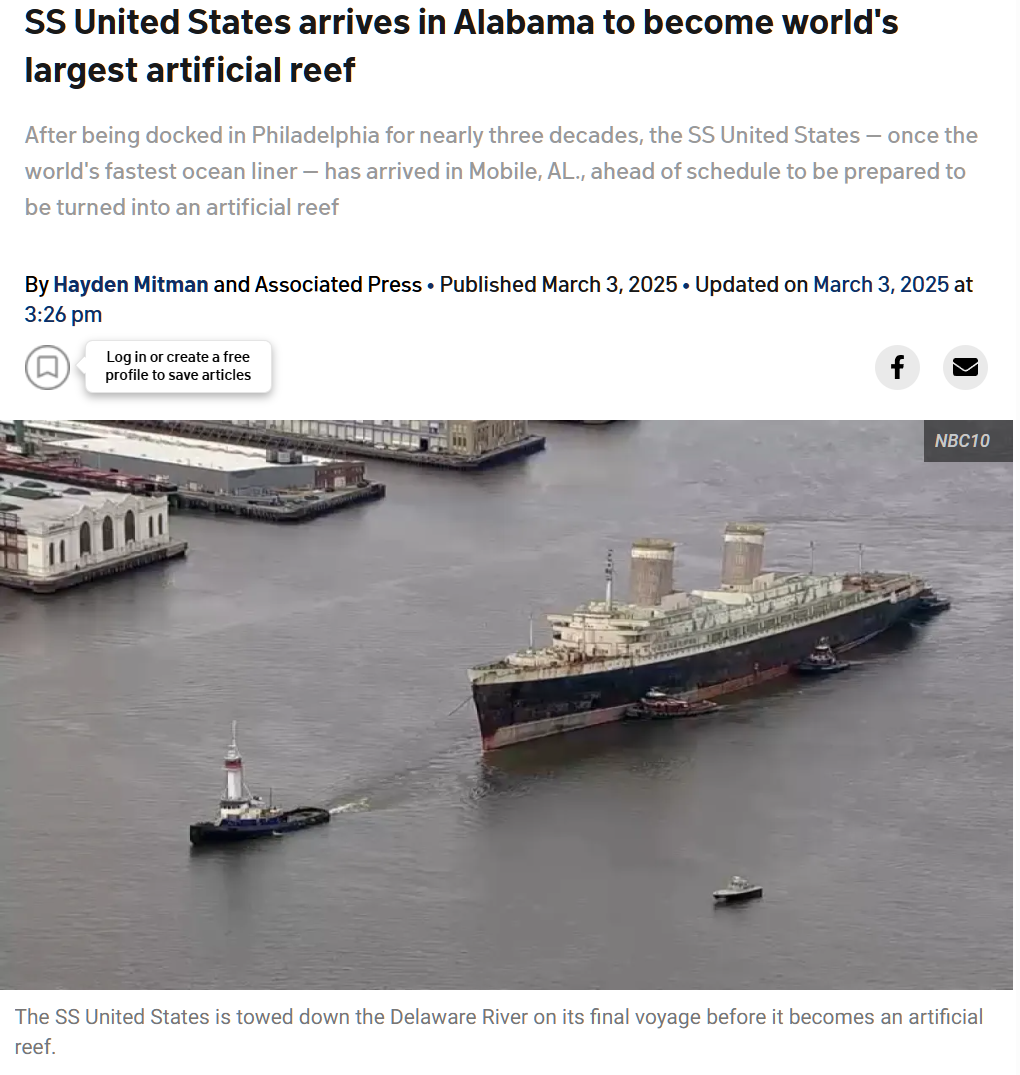

It costs 4-6X as much right now, I think, to make a ship in the U.S. compared to in Taiwan, Korea, or China (see Why you’re likely safer on a Panamanian- or Liberian-flagged ship than an American ship). The French, Germans, Finns, and Italians are all better/cheaper at making cruise ships than we are. Trump on shipbuilding sounds like someone who is 4’11” planning for a career in the NBA. Here’s one of the last memorable U.S.-built non-military ships (SS United States, built 75 years ago when the U.S. still had its WWII shipbuilding capacity):

This pains me:

And I also want to make interest payments on car loans tax-deductible, but only if the car is made in America. … Spoke to the majors today, all three, the top people, and they’re so excited.

The federal government has borrowed $36.5 trillion so far and will now encourage people to bury themselves in shiny car debt instead of paying taxes?

Trump describes the people who cowered in place for two years when instructed to do so by their governors:

From the patriots of Lexington and Concord to the heroes of Gettysburg and Normandy; from the warriors who crossed the Delaware to the trailblazers who climbed the Rockies; and from the legends who soared at Kitty Hawk to the astronauts who touched the moon, Americans have always been the people who defied all odds, transcended all dangers, made the most extraordinary sacrifices, and did whatever it took to defend our children, our country, and our freedom.

How did the world’s meekest people end up with this bold self-image?

Readers: What did you take away from the speech, if you watched?

The Democrat response (transcript) is from Elissa Slotkin, an archetypical member of her party (divorced childless menopause-age female passionate about expanding abortion care). She’s also an example of White men correctly perceive American Jews as their enemies? and Elite coastal Jews advocate discrimination against white and Asian males. For example, she promises to “Increase access to capital and other financial tools to support minority businesses” (but not to businesses owned by white men; source). Here’s an example of her rebuttal:

But securing the border without actually fixing our broken immigration system is dealing with the symptom not the disease. America is a nation of immigrants. We need a functional system, keyed to the needs of our economy, that allows vetted people to come and work here legally. So I look forward to the President’s plan on that.

(Doesn’t “America is a nation of immigrants” mean that Native Americans are irrelevant? Or maybe they’re not part of the “nation”?)

Is “an open border isn’t the real problem” persuasive? Isn’t this exactly what Joe Biden and Kamala Harris said?

But it’s also at risk when the President pits Americans against each other, when he demonizes those who are different, and tells certain people they shouldn’t be included.

She says that it is bad to “tell certain people they shouldn’t be included” but also has a web site telling white men they shouldn’t be included in a government hand-out program. Ms. Slotkin agrees with Donald Trump on one point:

We are a nation of strivers. Risk-takers.

She’s from a cower-in-place state (Michigan) where schools were still closed in 2022, roughly two years after SARS-CoV-2 began spreading in the U.S. and thinks that Americans are “risk-takers”?

It’s Congress’s job to set tax rates and determine spending, but Ms. Slotkin blames Donald Trump for deficit spending:

Meanwhile, for those keeping score, the national debt is going up, not down. And if he’s not careful, he could walk us right into a recession.

My conclusion from the two speeches: given our addiction to spending, the only thing that can save the U.S. from insolvency or hyperinflation is if LLMs and other forms of AI hugely expand the economy/tax base.

Loosely related, from the days when Congress accepted all of Ronald Reagan’s tax cut proposals and rejected all of his spending cut proposals:

Full post, including comments