Into the Storm: Two Ships, a Deadly Hurricane, and an Epic Battle for Survival by Tristram Korten offers us a window into an unusual lifestyle.

Ben Cournia, aviation survival technician (“rescue swimmer”), flight mechanic Joshua Andrews, and pilots Rick Post and Dave McCarthy show up to mosquito-infested Great Inagua Island (Bahamas) in September 2015 to be ready with a MH-60 Jayhawk in case undocumented importers need to be followed or people need to be pulled off ships or out of the water. They work two weeks on and two weeks off.

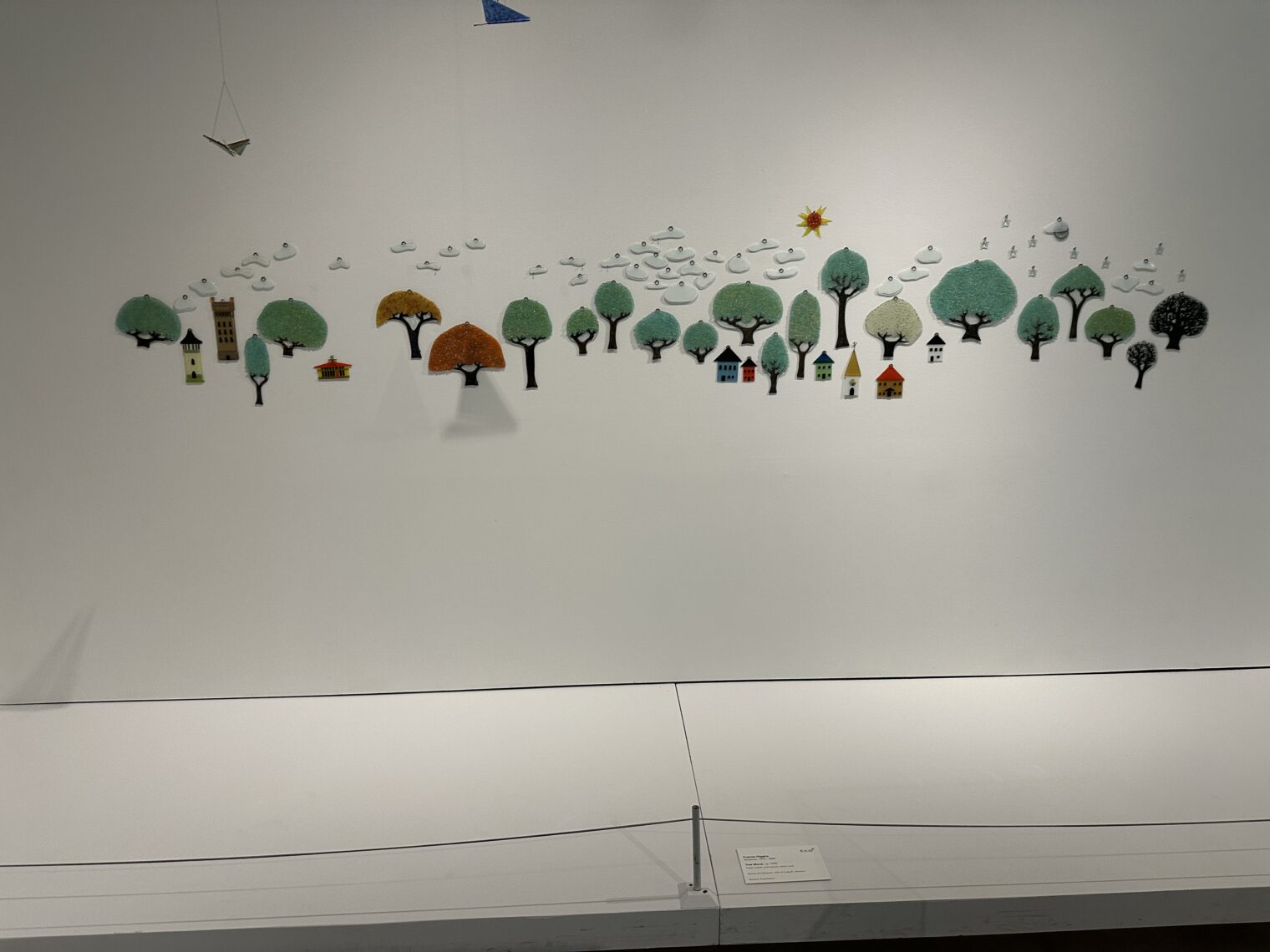

Here’s the machine, parked on the ramp in Portland, Maine in fall 2020 (see Maine/NH coast video)

This won’t be a story about diversity being our strength:

The four men made up a pretty good snapshot of the Coast Guard in terms of demographics (the service is overwhelmingly white) and disposition.

If there’s no racial diversity, maybe there is gender ID diversity?

Today there are 360 rescue swimmers spread out among twenty-six Coast Guard air stations. Three of them are women.

It also won’t be a story about the depredations of climate change. The deadliest hurricane season on record was almost 250 years ago:

Three back-to-back hurricanes in October 1780 killed tens of thousands of people and sank dozens of ships throughout the Caribbean and United States. The storms severely weakened the British Navy as it fought the American revolutionaries. The first storm struck Jamaica and then tore through Cuba, sinking British warships and collapsing whole towns, killing an estimated 3,000 people, half of them sailors. The second storm sped from Barbados to Bermuda, claiming roughly 4,300 lives. On the island of St. Vincent, a twenty-foot storm surge washed villages out to sea. On St. Lucia, the storm killed 6,000 people. About 9,000 more died in Martinique. Fifteen Dutch ships sank off Grenada. All told, this was the deadliest storm on record in the Western Hemisphere. Incredibly, another storm picked up within days and ripped through the region, smashing sixty-four Spanish warships sailing to take back the Florida panhandle from the British. Nearly 2,000 men died.

The Coast Guard was an early adopter of the helicopter, despite having missed out on Hanna Reitsch’s pioneering flights:

As soon as Coast Guard brass saw the public flight of Russian-born Igor Sikorsky’s prototype in 1940, they put in an order. In 1944, the Coast Guard conducted the first helicopter landings on a ship. The service’s first helicopter pilot, Frank Erickson, conducted the first helo rescue mission later that same year. Erickson and the Coast Guard’s helicopter detachment were stationed at the Sikorsky Aircraft plant in Connecticut to get trained by and work with the famed helicopter designer. Erickson collaborated with Sikorsky to develop power hoists for helicopter rescue missions and pioneered the idea of using stretchers to evacuate the injured.

Let’s leave the El Faro story and look at another ship, the Minouche. This one was also old (35 years), but not because of American protectionism. The Minouche went back and forth to Haiti with low-value cargo. She had a crew of 11 Haitians and a Filipino captain, Renelo Gelera. They didn’t make any obvious mistakes, according to the author, but Hurricane Joaquin still snuck up on them and sunk their ship from a distance of more than 100 miles (moderate winds, big waves, and an old engine that couldn’t be restarted after an automatic shutdown when the screw lifted out of the water).

The eye was now about one hundred miles north of Great Inagua. Tropical storm–force winds easily stretched over the rescue site. McCarthy mustered the helicopter and ground crews in the big hangar for a briefing. He explained the mission: cargo ship down, forty miles southeast, crew abandoning ship. He ran down a list of known risks. The main one, of course, was the weather—driving rain, high winds, extensive cloud cover. Then he asked if anyone had reservations. Silence. They may have assessed themselves as ready, but the truth was, this was virgin territory for the helicopter crew. None had flown in conditions this extreme before, except maybe Cournia during his tour in Alaska, much less conducted a search and rescue operation in a hurricane—at night. Most civilian helicopters won’t take off in 20-knot winds. The MH-60 has a wind limitation of 60 knots off the nose and 45 from any other direction for takeoff. The Coasties were heading out in 35-to-40-knot winds with gusts up to 60.

(Tech correction: 20 knots was our wind limit for doing sightseeing tours over Boston in the Robinson R44. A good practical limit for lessons at the flight school was 30 knots (not for a beginner student, though). I remember a successful photo mission with winds of 35 knots. We landed with surface winds gusting to about 30 knots on the last leg of the helicopter trip from Los Angeles to Maskachusetts. There is no wind limitation for the R44, but I would say that you’d need a good reason to operate with surface winds over 30 knots if there were any nearby hills (a formula for turbulence). The Jayhawk is 10X heavier than an R44 and should be much more stable.)

Not to spoil the suspense, but Ben Cournia was able to get the sailors out of their life raft and into the basket for hoisting. He was in the water for hours. The first trip to the stricken vessel involved about four hours of hovering over the raft. The second trip involves some ugliness and a save by a technology:

Post, who couldn’t see anything out the windshield, was flying almost entirely by his instrument panel. His altitude was good, but his hover bar showed him moving even though he felt as if the aircraft was stationary. His mind couldn’t reconcile how his body felt with what the instruments said. This was a dangerous sensation for a pilot. Vertigo could set in and the pilot could think up was down, and try to fly accordingly. He needed to reestablish some frame of reference. Post alerted his crewmates that he was having trouble staying oriented. He hit the “auto depart” button, which takes control of the Jayhawk and lifts it three hundred feet in the air, then reestablishes an even longitudinal hover. It’s a reset, a way for the pilot to start over and try again. From there, Post knew which way was up.

I’m not sure what the author means by a “hover bar” instrument and I haven’t heard of an “auto depart” button, though I know that the various versions of the Blackhawk have some advanced automation, e.g., to approach to a point in space or fly a predefined search pattern.

After some instability combined with a big wave grabbing the basket, the winch cable gets damaged and they return to base to check out a second helicopter and make a third visit to the life raft. There was a whole second crew available to fly that second helicopter, so I don’t understand why the exhausted first crew went out yet again (“you have to go out, but you don’t have to come back” surely doesn’t mean that one crew relaxes in the ready room while the first crew goes out three times, does it?). Obviously there was some learning that had happened on the first two trips, but a member of the first crew could have gone out with the fresh/rested second crew as an advisor.

Just when you think that the weather and waves are bad, Katherine Clerk Maxwell’s equations zap you:

As the basket was hoisted, Cournia hung on to minimize swing, and as he was lifted out of the water he felt a sudden jolt pass through his entire body. It was so strong that it locked his arms in a spasm of convulsed muscle. He tried to free his grip but couldn’t. Eventually the jolt passed and Cournia was able to drop back into the water. A special static discharge cable—which had been attached to the basket to siphon excess electricity generated by the helicopter’s blades cutting through the air—had somehow ripped off, and a current of electricity had passed from the helicopter’s metal frame down the cable to the basket. This meant Cournia had to be extra careful to make sure the basket was in contact with the water whenever he touched it, in order to provide a ground for the electricity.

In case you were wondering, I love Into the Storm: Two Ships, a Deadly Hurricane, and an Epic Battle for Survival almost as much as I love the Coast Guard (and who doesn’t love the Coast Guard?). Just don’t start reading it before bedtime because it’s tough to put down.

Related:

- the book will inspire you to carry a PLB or EPIRB even if you’re just heading out to the grocery store!

Full post, including comments