From Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World:

As a regular solo customer of Delmonico’s, the polite and gracious inventor had let the highly trained staff know that he liked to have eighteen pristine napkins in a stack at his table. Very discreetly, Tesla used them to wipe the germs off each piece of heavy silverware, sparkling china, and crystal stemware before he partook of the chef’s many delights. Tesla’s germ phobia had developed after a fellow scientist allowed him to observe through a microscope the many normally invisible creatures inhabiting unboiled water. Tesla would later explain, “If you would watch only for a few minutes the horrible creatures, hairy and ugly beyond anything you can conceive, tearing each other up with the juices diffusing throughout the water—you would never again drink a drop of unboiled or unsterilized water.” So Tesla was ever vigilant in limiting his exposure to these vile microscopic bugs.

(Thank you to Steve for the Amazon gift card and suggestion to use it on this book!)

Nikola Tesla was also a pioneer in social distancing:

More and more [in the 1930s], Tesla lived in his own world, as big a romantic as ever, and as eccentric. He had his vegetarian meals specially cooked by the hotel chef and insisted that the help not get closer to him than a few feet, part of his phobia of germs.

How about #FollowScience and #BelieveTheExperts?

And in fact, on May 6, 1893, the officers of the Niagara Falls Power Company declared unequivocally that polyphase alternating current would be their choice. This was, at the time, still a very bold and highly controversial stance. The eminent Sir William Thomson, chairman of the International Niagara Committee and just elevated to become Lord Kelvin by Queen Victoria, cabled Adams on May 1 to head off the announcement. He proposed an ambitious DC plan, urging, “Trust you avoid gigantic mistake of adoption of alternate current.”

In other words, one of the greatest scientists of the age was sure that low-voltage DC was the way to electrify a country.

BLM at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition (named after someone who refused to #BelieveScience and lit up by Westinghouse AC):

On the hot Friday of August 25—Colored People’s Day at Festival Hall—the great abolitionist and leader Frederick Douglass wearily entreated in this era of Jim Crow, “All we beg is to receive as honest treatment as those who love only part of the country.”

How rich was the pre-electrified country?

… [in 1890] America’s population up to a mighty sixty-three million, according to the recent census. Politicians had taken to boasting that the United States was now a “billion dollar” country. It was, in fact, far richer than that, thanks to its relentless can-do commercial spirit and the reckless ambition of men like Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse. In the postbellum United States, the national wealth had soared to $65 billion, more than the accumulated holdings of all the aristocrats and commercial classes of Great Britain, Germany, and Russia combined. By 1890, in America, nearly $40 billion was invested in land and buildings, $9 billion in the sprawling network of railroads, and $4 billion in manufacturing and mining.

In other words, roughly $1,000 in wealth for every resident, roughly $28,000 in today’s mini-dollars. The U.S. had a net worth of $124 trillion as of 2014 (Wikipedia, assets minus debts). Population back in 2014 was 318 million (compare to 330.1 million today). So the per-person wealth in 2014 was $390,000, about $430,000 in 2020 dollars.

How did folks in New York City entertain themselves back then?

As an appalled Parkhurst and his two companions toured every kind of beer-soaked dance hall, cheap saloon, and sleazy brothel, they became astonished, genteel witnesses to a large and rowdy underworld thriving on illicit gambling, cheap liquor and beer, and organized, commercial sex catering to every kind of appetite. Gardner also had his own detectives out gathering affidavits. So when Reverend Parkhurst mounted his pulpit a mere month later on Sunday, March 13, 1892, he possessed documented evidence that Tammany was “rotten with a rottenness that is unspeakable and indescribable.” He had proof that 254 saloons and 30 brothels had been roaring with business just the previous Sunday. In the ensuing months, a grand jury handed down a few placating indictments, but little would change immediately. The urban poor (and a certain number of their better-off confreres) wanted jollity and dazed forgetfulness, be it craps, bawdy dance halls, or cheap, quick sex, for theirs were hardscrabble lives.

Reverend Parkhurst would be a big fan of coronashutdown!

George Westinghouse might not have been. In response to Edison’s arguments that high-voltage AC was dangerous, he responded that, statistically, electrocution was an uncommon cause of death:

Westinghouse tried to put it into perspective with the following: In the year 1888, sixty-four people in New York City were killed in streetcar accidents, fifty-five by omnibuses and wagons, twenty-three by illuminating gas, and all of five by electric current. This was not exactly an orgy of wanton and careless killing.

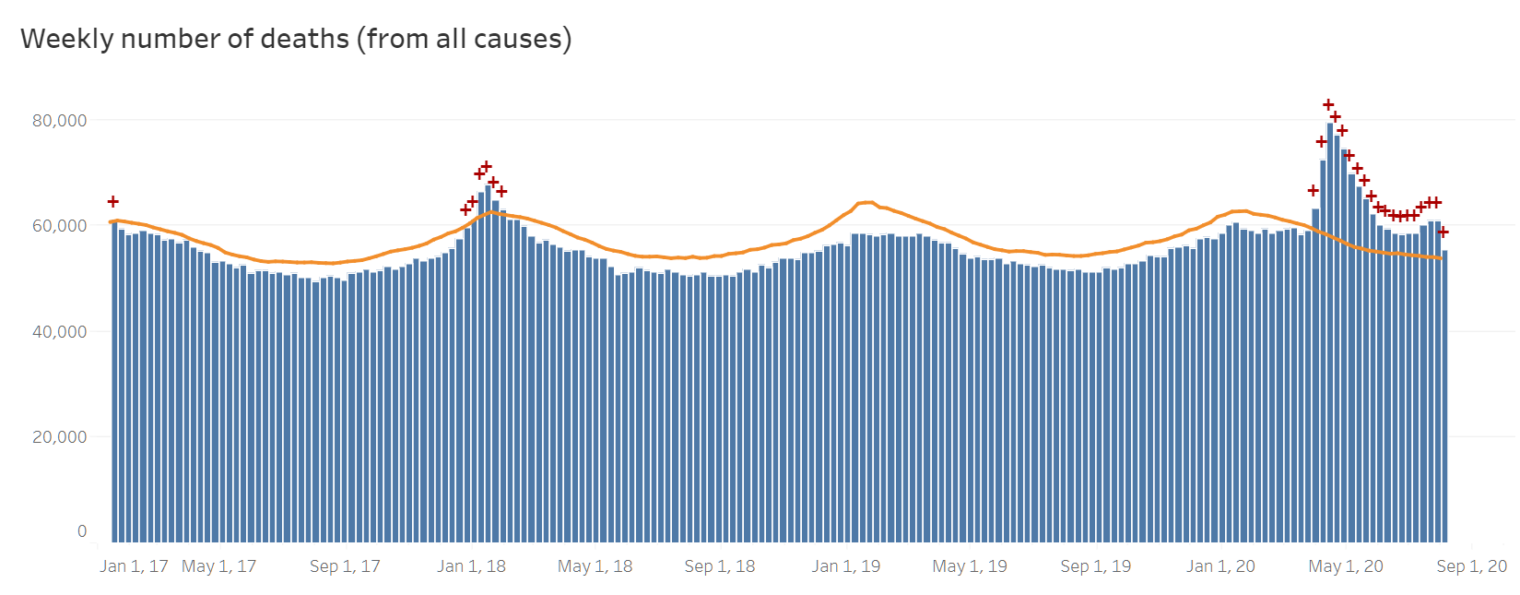

Westinghouse might have referred to the CDC’s excess deaths chart:

Speaking of death, there was a huge amount of enthusiasm for capital punishment via high voltage.

Two physicians leaned forward to examine Kemmler [the first electric chair victim]. The other doctors gathered around and dented Kemmler’s flesh to judge his state. Dr. Southwick smiled broadly as he came away from the fresh corpse. “There,” he exclaimed to a knot of witnesses who had quietly withdrawn to the far end of the chamber, “there is the culmination of ten years’ work and study. We live in a higher civilization from this day.”

Higher civilization wasn’t completely civilized…

But the blood was continuing to ooze from Kemmler’s small finger wound. His heart still had to be beating. The physicians around the limp figure recoiled as one yelled in horror, “Great God! He is alive!” Another ordered, “Turn on the current.” “See, he breathes,” gasped a third. When Dr. Southwick and the others whirled around at these cries, they saw that Kemmler’s body was still limp, but his chest was heaving up and down. He seemed to be struggling for breath, and foam was seeping horribly from his masked mouth hole. “For God’s sake, kill him and have it over!” screamed one witness. The Associated Press reporter fainted on the wood floor, and several men carried him to a bench, where they fanned him. Durston had turned chalk white. He fumbled and reattached the scalp electrode. As the current flowed anew and Kemmler again went horribly rigid, “an awful odor began to permeate the death chamber.” Kemmler’s hair and skin were being visibly singed. A blue flame played briefly behind his neck. His clothes caught fire, but one of the doctors quickly extinguished them. “The stench,” reported the Times, “was unbearable.” After several minutes, the current was turned off, and as purple spots mottled Kemmler’s hands, arms, and neck, the doctors again declared him dead. The room reeked of burned meat and feces. The nauseated witnesses signed the death warrant for Warden Durston and then trailed out into the stone corridors, silent, shaken, several sick, the Erie County sheriff so distraught that tears trickled down his face. Three hours later, when the doctors had sufficiently recovered to perform an autopsy, they found that rigor mortis had stiffened Kemmler into a permanent sitting position. Examination of the body showed scorch marks wherever the electrodes and buckles touched the body. Kemmler had been “roasted” as well as a piece of overdone meat. Once the autopsy was complete and numerous organs removed, Kemmler’s baked corpse was taken and buried at night in the prison courtyard with great quantities of quicklime to dissolve all ultimate traces.

The author chronicles the cruelties inflicted on innocent animals, such as dogs and calves, in the years leading up to the execution of convicted criminals via electricity. This was the work of Edison affiliates, anxious to paint the Westinghouse AC system as dangerous.

Investment advice from Tesla turned out to be almost as bad as investment advice from Paul Krugman (November 2016: “It really does now look like President Donald J. Trump, and markets are plunging. When might we expect them to recover? … If the question is when markets will recover, a first-pass answer is never.”):

And what of Niagara Falls? the local reporters urgently asked. Tesla replied without hesitation: “The result of this great development of electric power will be that the falls and Buffalo will reach out their arms and will join each other and become one great city. United, they will form the greatest city in the world.”

(See “Can Buffalo Ever Come Back?” (2007), in which we learn that “The 1920s were the last real growth period for Buffalo” and that rail and road transportation reduced the importance of the Erie Canal. “Then the Saint Lawrence Seaway opened in 1957, connecting the Great Lakes to the Atlantic and allowing grain shipments to bypass Buffalo altogether.” Meanwhile “New York’s high taxes, burdensome regulations, and pro-union laws made Buffalo less attractive to employers than its more successful southern competitors. … Despite 50 years of population loss, Buffalo has one of the steepest metropolitan tax burdens in the country—including one of the nation’s highest local property tax rates, according to a 2003 study.”)

Vaguely related, the Glen Canyon Dam, circa 1990, captured with Kodak Tech Pan film:

It was legal to go to the Canadian side of the Falls just a year ago!