I’ve been listening to Return from the Stars, which Stanisław Lem wrote in 1961. The book is set in approximately 2088 when a 40-year-old astronaut returns to Earth after 127 years of high-speed travel with consequent time dilation.

Lem’s vision of economics is pure Marx. Despite a proliferation of humans, there is no scarcity. Not only is electricity too cheap to meter, but also apartments, food, clothing, and transportation. It is unclear how this happened, but perhaps it is due to robots, which are the workers in restaurants and hotels (also free). On the third hand, the novel describes a “real” star who lives in a fabulous suburban villa. So there are some people who live way more luxuriously than others, but there is no mechanism for dealing with scarcity for lifestyle items.

Lem envisions the Kindle (on which Return from the Stars is now available), but not a public computer network to fill it up with content. (Computer networking existed in 1961, but the packet-switched wide-area networks with which we’re familiar weren’t conceived of for another few years.)

I spent the afternoon in a bookstore. There were no books in it. None had been printed for nearly half a century. … No longer was it possible to browse among shelves, to weigh volumes in the hand, to feel their heft, the promise of ponderous reading. The bookstore resembled, instead, an electronic laboratory. The books were crystals with recorded contents. They could be read with the aid of an opton, which was similar to a book but had only one page between the covers. At a touch, successive pages of the text appeared on it. But optons were little used, the sales-robot told me. The public preferred lectons—lectons read out loud, they could be set to any voice, tempo, and modulation. Only scientific publications having a very limited distribution were still printed, on a plastic imitation paper. Thus all my purchases fitted into one pocket, though there must have been almost three hundred titles. A handful of crystal corn—my books. I selected a number of works on history and sociology, a few on statistics and demography, and what the girl from Adapt had recommended on psychology. A couple of the larger mathematical textbooks—larger, of course, in the sense of their content, not of their physical size. The robot that served me was itself an encyclopedia, in that—as it told me—it was linked directly, through electronic catalogues, to templates of every book on Earth. As a rule, a bookstore had only single “copies” of books, and when someone needed a particular book, the content of the work was recorded in a crystal.

The originals—crystomatrices—were not to be seen; they were kept behind pale blue enameled steel plates. So a book was printed, as it were, every time someone needed it. The question of printings, of their quantity, of their running out, had ceased to exist. Actually, a great achievement, and yet I regretted the passing of books. On learning that there were secondhand bookshops that had paper books, I went and found one. I was disappointed; there were practically no scientific works. Light reading, a few children’s books, some sets of old periodicals.

So the bookstore is somehow linked via a network, but the network can’t reach into homes or pockets. Speaking of pockets, Lem did not anticipate wearable or pocketable technology. There are no smartphones. There is no email. People send telegrams at “the post office” (Lem didn’t imagine that Bad Orange Man would dismantle this institution in 2020!).

Lem envisions a world of fantastically advanced construction technology. Although the city of 1961 looked a lot like the city of the 1830s, he expected the cities of the 2080s to be spectacularly different. I.e., the very field that has been most stagnant he expected to undergo the most dramatic changes and the very field that has seen skyrocketing costs he expected to become almost free. (Again, maybe the prediction is based on the fact that Lem has envisioned a world in which there are 18 robots for every human.)

Lem correctedly predicted the end of monogamy (some real life history). There are still marriages, but they are brief and easy for one partner to dissolve unilaterally (not too many couples have children, so litigation over profitable child support isn’t possible). An old doctor advises the returned astronaut:

Once, success used to attract a woman. A man could impress her with his salary, his professional qualifications, his social position. In an egalitarian society that is not possible. … Take in a couple of melodramas and you will understand what the criteria for sexual selection are today. The most important thing is youth. That is why everyone struggles for it so much. Wrinkles and gray hair, especially when premature, evoke the same kind of feelings as leprosy did, centuries ago . . .

In other words, it is just like Burning Man!

Marriages, to the extent people bother with them, last about seven years before people move on to new/additional sex partners. Perhaps more commonly, marriages end automatically after a one-year trial period.

Lem completely misses the LGBTQIA+ rainbow wave. Nobody in the novel changes gender ID. Everyone identifies as a “man” or a “woman”. Cisgender heterosexuality now, cisgender heterosexuality tomorrow, cisgender heterosexuality forever!

On the other hand, the OLED section at Costco would not have surprised Lem:

I realized that what I had in front of me was a wall-sized television screen. The volume was off. Now, from a sitting position, I saw an enormous female face, exactly as if a dark-skinned giantess were peering through a window into the room; her lips moved, she was speaking, and gems as big as shields covered her ears, glittered like diamonds.

Big TVs are used as ceilings with video feeds so that everyone in this heavily populated Earth can see the sky.

Lem completely missed coronaplague and the terrified flight to the suburbs and exurbs. The multi-level cities he created would be the perfect breeding ground for an enterprising virus. On the other hand, he foresaw that humans would become dramatically more risk-averse and therefore it is fair to say that he foresaw cower-in-place as a response to the novel coronavirus. On the third hand, in trying to understand how an astronaut died, a character asks “Could he have had a corona?” (maybe we need to adopt this coinage?)

Lem is stuck in the European perspective that children are products of marriage (US vs. Europe stats). There are no “single parents” in the novel. But children are also essentially products of eugenics. Those who can’t pass an exam can’t breed:

It was considered a natural thing that having children and raising them during the first years of their life should require high qualifications and extensive preparation, in other words, a special course of study; in order to obtain permission to have offspring, a married couple had to pass a kind of examination; at first this seemed incredible to me, but on thinking it over I had to admit that we, of the past, and not they, should be charged with having paradoxical customs: in the old society one was not allowed to build a house or a bridge, treat an illness, perform the simplest administrative function, without specialized education, whereas the matter of utmost responsibility, bearing children, shaping their minds, was left to blind chance and momentary desires, and the community intervened only when mistakes had been made and it was too late to correct them. So, then, obtaining the right to a child was now a distinction not awarded to just anyone.

What’s the technology by which risk has been eliminated from this timid society?

Every vehicle, every craft on water or in the air, had to have its little black box; it was a guarantee of “salvation now,” as Mitke jokingly put it toward the end of his life; at the moment of danger—a plane crash, a collision of cars or trains—the little black box released a “gravitational antifield” charge that combined with the inertia produced by the impact (more generally, by the sudden braking, the loss of speed) and gave a resultant of zero. This mathematical zero was a concrete reality; it absorbed all the shock and all of the energy of the accident, and in this way saved not only the passengers of the vehicle but also those whom the mass of the vehicle would otherwise have crushed. The black boxes were to be found everywhere: in elevators, in hoists, in the belts of parachutists, in ocean-going vessels and motorcycles.

The other core technology is modifying humans in early childhood via “betrization,” which renders them incapable of perpetrating violence.

So… the big misses for this futurist were (1) Internet, (2) battery-powered personal electronics, (3) portable communication, and (4) stagnation, not innovation, in architecture and construction.

(Lem also failed to predict a world obsessed with politics. There are no materially comfortable people protesting BLM or anything similar in Return from the Stars. Material comfort has apparently made people content with whatever the government is. Lem didn’t anticipate that the richer a society got the more pissed everyone would be!)

More: read Return from the Stars.

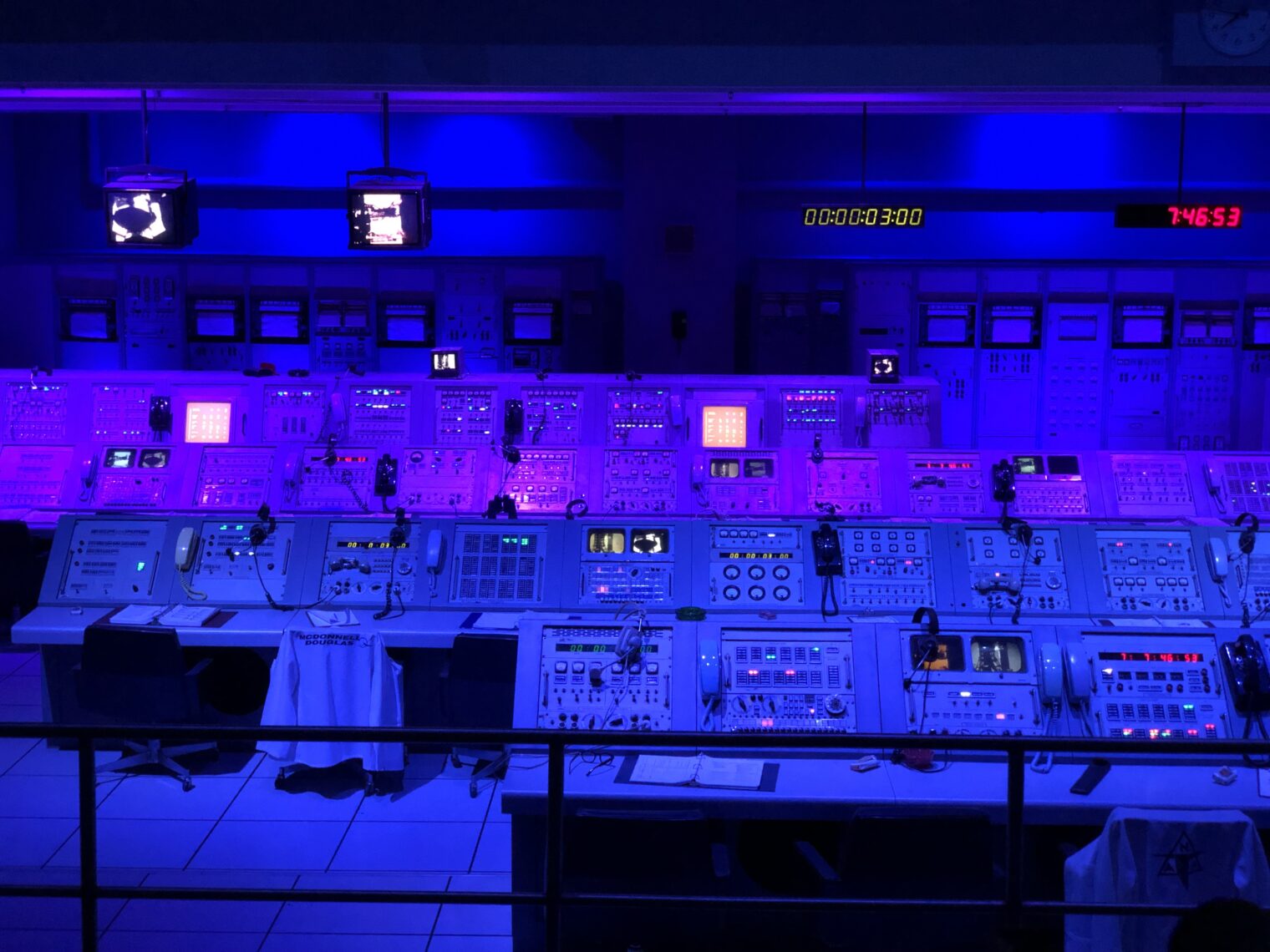

As close as we’ve gotten in the pre-Musk/Bezos era… (from the Kennedy Space Center’s visitor center)

I haven’t read it, but did Lem anticipate that in order to maintain control over populations it would continue to be necessary to guarantee that only certain people have access to the best and clearest information about important upcoming scientific developments? He didn’t anticipate the Internet, per se, and even with the Internet, there’s a tremendous disparity between people in Senior Management throughout the world in terms of who gets the really good inside information first. Witness the Pfizer vaccine success. I’m quite sure Angela Merkel knew that today’s announcement was impending, at least two weeks ago.

When I worked for the Law School in Chicago, one of the most important things I learned was that the real difference between the Decisionmaking people and the Decisionmaked people was the information disparity. In other words, it would be possible for almost anyone of slightly-higher-than-average IQ to run a law school effectively, if they had access to the same information the Dean has. In Lem’s ultra-egalitarian world, does he talk about that at all?

For example, you recently linked to Courthouse News Service, which I can only guess you watch because of the work you do involving software litigation. I’d forgotten about them recently, but it’s pretty high-quality information and you can’t just subscribe to it with a gmail address: you have to be affiliated with a law firm. But it’s unquestionably a lot less “bullshitty” than most of the media regular old Deplorables read. Really clear stuff with zero clickbait, no media personalities, and no advertisements to distract your attention from what’s going on. In Lem’s future world, does he mention that’s the only way to make sure the people running things remain in control (aside from making it impossible to be violent?)

https://www.courthousenews.com/biden-win-brings-relief-in-europe-realigns-world-politics/

We have 68 years to get to 2088, so the future still has time to catch up with Lem.

I was thinking about print books while sitting on the throne, reading one. The old trope of spending Sunday with the New York Times on the seat of ease is out-of-date. To what extent do changing lavaratory reading habits affect our consciousness? It may seem like a silly question, but speaking from personal experience, it is an important one.

I wonder if by 2088 society will come to the realization that being constantly connected is a net loss for quality of life?

I used to know someone who told me quite clearly that she came up with her best ideas while she was laying in bed, barely awake, lucid dreaming. I think that was a nice way to say she got them while sitting on the toilet, but I’ll never know for sure.