A very loose companion to my own “Women in Science” piece (“Pursuing science as a career seems so irrational that one wonders why any young American would do it.”)… an article by an English professor who was fired (“denied tenure”) at Yale:

what disgusted me the most was not the intellectual corruption. It was the careerism. It was the sense that all of this—all the posturing, all the position-taking—was nothing more than a professional game. The goal was advancement, not truth. The worst mistake was to think for yourself. People said things that they obviously didn’t believe, or wouldn’t have believed if they had bothered to subject them to the test of their own experience—that language is incapable of making meaning, that the self is a construct—but that the climate forced them to avow. Students stuck their fingers in the air to see which way the theoretical winds were blowing, designing their dissertations to catch the swell of the latest trend.

I managed to publish a couple of articles and get some decent recommendations from professors over 50, and when I ventured on the job market, the year I finished my degree, I was offered interviews at five institutions (out of the 20 to which I applied). Four were lower-tier places—Auburn, the University of Montana, Georgia State, and Cal State Los Angeles—and the fifth was Yale. The explanation of this strange assortment is that Yale’s was still a very conservative department—meaning, it was still run by people who shared my intellectual values. Being able to write, for example, was not considered a liability.

After nine years in graduate school, uncertain the entire time about my future, I had been granted a new lease on my professional life. Given Yale’s generous 10-year timeline, plus leaves of absence in the fourth and seventh years, I should’ve been able to make it work: publish, get another job, make it to Castle Tenure.

For those getting ready to pony up tuition, room, and board at a research university:

The problem with spending time with students, or on students, or writing book reviews or essays, is that none of those activities do anything for you professionally. Academics are rewarded for one thing and one thing only: research. Scholarly publication. Nothing else counts; anything else is a step toward professional suicide.

After he can’t get tenure at Yale?

… 39 schools and 46 applications. Prestigious universities, public and private; non-prestigious universities, public and private; Canadian universities; liberal arts colleges. Institutions in the Northeast, the Midwest, the South, the West, and north of the border; schools urban, suburban, and rural. I would’ve gone just about anywhere. But with all that work and all that hope, I got a total of five interviews, two callbacks (the final stage in the hiring process), and zero offers.

At this point he’s presumably mid-40s, a time when an intelligent hard-working person is reaching the zenith of his/her/zir/their career prestige, and unemployable within his field.

I recommend this essay if you know anyone who is considering investing in a Ph.D.!

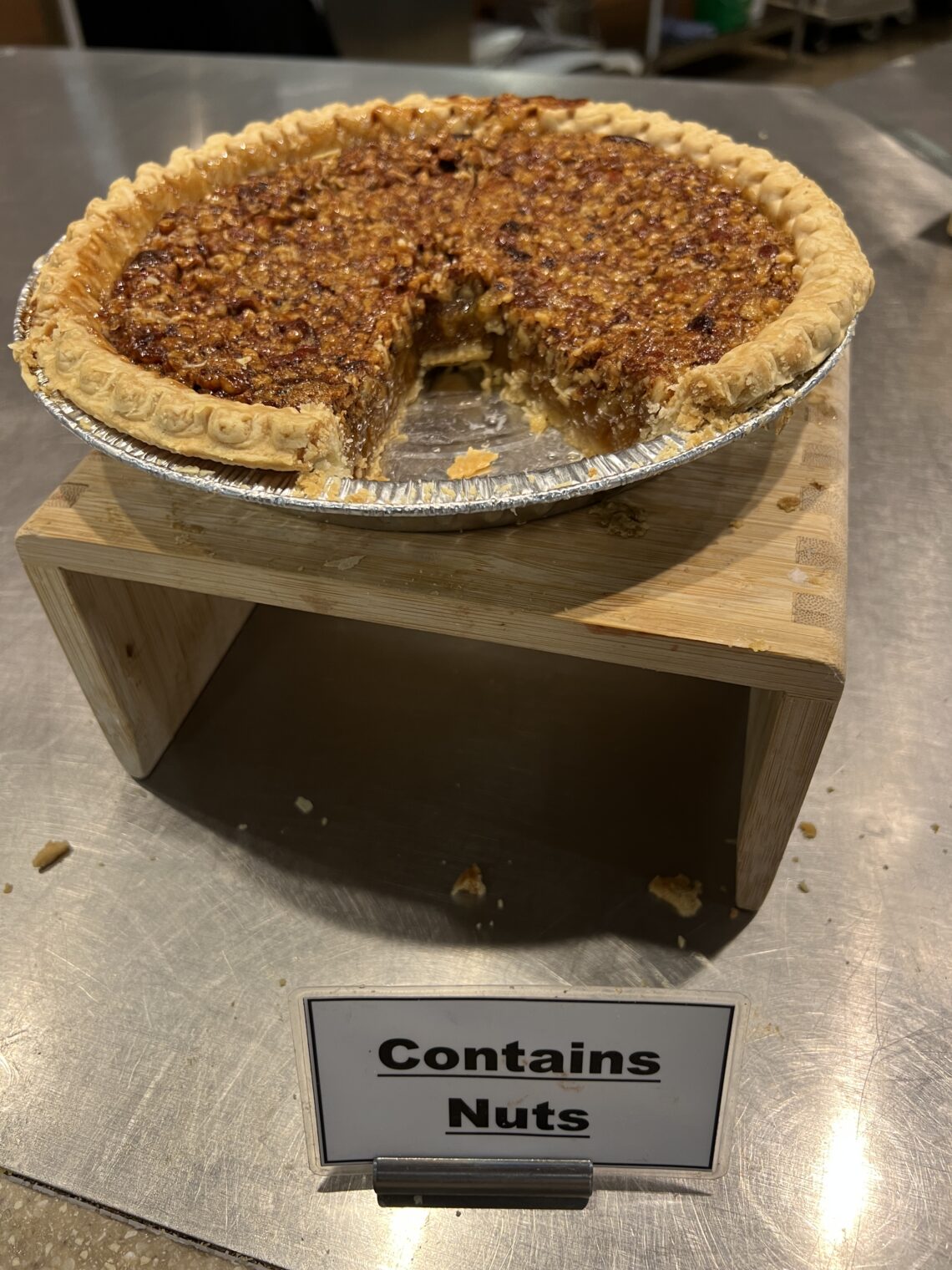

Finally, this seems like a good time for me to remind everyone that the cafeteria staff at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh needs to remind the academic geniuses that pecan pie contains nuts:

Yup. This rot has been growing for several decades. I’ll have more on tha when I finish reading the article, I’m about 2/3rds through it.

In my opinion the best place to be in academia is a nice, safe, semi-permanent administrative position like “Operations Manager” or “Faculty and Programs Assistant” – basically slightly glorified secretarial just below the highest echelon. You’ll have a 25 or more year career, good-to-great pay depending on the school, and of course the generous benefits package, retirement plan and credit union, the academic discounts on things like software and museums, etc. You won’t make enough to eat expensive french food *every* night, but in a lot of places you’ll become a denizen of the hip, local Campus Community with all its Progressive quirks and artsy pretensions. You can use the school’s recreational and athletic facilities. There are dozens of perks.

It’s almost always a 9-5 job, four or five days a week, with generous compensation. You don’t have to do any research, you don’t have to teach, you don’t have to travel to boring conferences to network with important people – you just keep your head down, keep the machine running, and make sure you know all the latest buzzwords and the latest hand signals and codes, so you don’t accidentally step on a landmine and have a hotshot young Critical Theorist call you a racist or worse. Occasionally someone has to have your back when one of the Angry Professors gets a hair across their proverbial arse and starts talking about you in a language that cannot convey meaning.

I know several people who are still doing just that at the University I worked for, and after almost 20 years I completely understand why they never tried to find a new career or “move up” by getting an advanced degree and playing the game of Marxist Chutes and Ladders the author describes. I remember at least two of them who claimed they were only taking the job “temporarily” – that was almost two decades ago! Apart from being a State Trooper or a police officer in a wealthy town, what my old co-workers are doing are some of the best jobs in the country. Endosymbiont parasites in a benevolent host, in other words. I’m sure they’d object to that characterization but I really do mean it in the best way possible.

Addendum: Also, having a job like that makes voting and political thinking simpler, because all you have to do is go with the flow, which only moves in one direction 95% of the time. It’s low-stress! Sometimes you have to do semi-menial and boring things like proctor exams or attend to the mail room for a professor who is away at an academic conference or visiting another school, etc., but those things are a trifle when compared to the benefits. You just have to make sure you think correctly, at least while you’re at work.

But almost every job is like that now, isn’t it?

Also, I’ve found that many Universities are pretty “liberal” when it comes to things like side gigs you might pursue to make some extra spending money, so long they don’t affect your 9-5 job performance and HR review.

You’ll never have a “Ph.D.” after your name, nobody will ever call you “Doctor” and you won’t have a CV 10 pages long or be interviewed on National Public Radio, but it’s a pleasant life, all things considered.

One of the worst career decisions I ever made (among several) was, twenty years ago, turning down a (non-faculty) job offer with a large southern state university. I chose a private-sector job because it paid $7000 more per year (I only lasted two stressful years).

@DP: I get it, believe you me. I think they can keep this up for another 10 or 20 years at least, until the whole house of cards collapses or we are a nation at war, whichever comes first.

@DP: I’m not sure, though, that people who do so much to support higher education are very concerned about the Marxist rot that has basically taken over the institutions they generously support. I think they mostly do it to call themselves “philanthropists” and avoid any concrete actions that might stop the spread of the disease before it kills the entire country, which it will.

They’re wimps. They don’t want confrontation – they want accolades and celebration. But eventually the Marxists will come for them, too, it’s inescapable.

Important reminder that Airventure is still in the flyover states, where brain power hasn’t exactly caught up with 50,000 years ago.

Lion you are a dumb dumb!

LOL, lion, you need to get out of your mom’s basement (or faculty lounge… which is basically the same) more often. You may discover that there’s a whole world outside populated with all kinds of people, a lot of whom live in the “fly-over” states. Some of them are much smarter than any professor out there – and have real-life achievements to show for that.

Like it or not, but success in academia boils down to approval from one’s “peers”, even in STEM. Winning popularity contests is not the same as actually doing something worthwhile.

Typical example of coastal brainpower: Samuel Langley, who was one the first to make federal financing fly.

Typical example of luck of coastal brainpower: Wright brothers. who made fist powered heavier then air flight on a shoestring budget

If there is one thing that contains nuts, it’s the academic community.

Fazal: They’re sane enough to keep supporting the political party that offers them taxpayer cash via subsidized student loans, forgiven student loans, etc.

@Fazal:

This is the sort of student I tell to quit our PhD program after they get their master’s degree: of course this guy failed, he literally hates the actual job of being a professor. (That he wishes the job was different puts him closer to today’s Zoomers than he is probably willing to admit.)

Yes, I thought so too. What a zoomer. He would rather teach students and write books, then enjoy being a pompous prick.

The article from Deresiewicz was telling, and I don’t see how it does anything to support his case.

A compelling case would be something like “I made all the important discoveries or made insightful arguments that pushed the field forward, and I’m going to give you details”, but there was none of that.

I would even accept “I wrote the best-researched biography of someone that only 12 people know”, but there wasn’t even anything like that.

It reads like “Why didn’t the other stay-at-home dads in the reading club agree with me? They just wanted to do things that helped their career.”

Reading between the lines, it draws a picture of a job that delivers nothing useful, with no archors to determine value, so it comes down to petty fights and trend-following as everyone tries to best to figure out what’s important in a field where nothing is actually important.