A timely book… The Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the American Economy (2022) by Christopher Leonard.

Motivation…

First, since this is a political book let’s look at the author’s background politics. He is particularly hostile to the Tea Party,

If the Tea Party had a single animating principle, it was the principle of saying no. The Tea Partiers were dedicated to halting the work of government entirely.

An aging population relied more and more heavily on underfunded government programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security,

The existence of these Deplorables kept the reasonable Democrats and Republicans in Congress from doing great work via government spending, thus putting pressure on the Fed to act. The Fed’s rash actions may thus be laid at least partly at the doors of the haters. Also, the best characterization of the world’s most expensive health care programs, as a percentage of GDP, is “underfunded”. Without the Tea Party, every Medicaid beneficiary would get a weekly gender reassignment surgery? The author expresses his dream that more American workplaces would become unionized.

What’s the scale of the Fed’s recent money-printing?

Between 1913 and 2008, the Fed gradually increased the money supply from about $5 billion to $847 billion. This increase in the monetary base happened slowly, in a gently uprising slope. Then, between late 2008 and early 2010, the Fed printed $1.2 trillion. It printed a hundred years’ worth of money, in other words, in little over a year, more than doubling what economists call the monetary base.

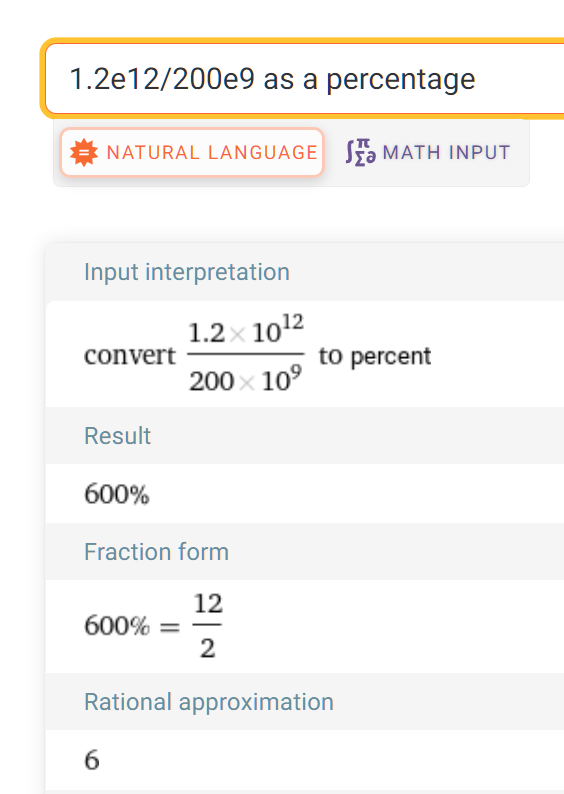

The amount of excess money in the banking system swelled from $200 billion in 2008 to $1.2 trillion in 2010, an increase of 52,000 percent.

Maybe the author and Simon and Schuster are using coronamath? What if they’d asked Wolfram Alpha about this ratio? The answer would be a 600 percent ratio or 500 percent increase, not 52,000 percent.

Whatever the percentage might have been, quantitative easing was going to be good news for the rich:

The FOMC debates were technical and complicated, but at their core they were about choosing winners and losers in the economic system. Hoenig was fighting against quantitative easing because he knew that it would create historically huge amounts of money, and this money would be delivered first to the big banks on Wall Street. He believed that this money would widen the gap between the very rich and everybody else. It would benefit a very small group of people who owned assets, and it would punish the very large group of people who lived on paychecks and tried to save money.

Perhaps no single government policy did more to reshape American economic life than the policy the Fed began to execute on that November day, and no single policy did more to widen the divide between the rich and the poor. Understanding what the Fed did in November 2010 is the key to understanding the very strange economic decade that followed, when asset prices soared, the stock market boomed, and the American middle class fell further behind.

According to the book, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen (U.S. Treasury Secretary today, at least until my prediction of Sam Bankman-Fried taking over comes true) were the Fed’s biggest cheerleaders for quantitative easing while Thomas M. Hoenig was the biggest opponent, partly due to concerns about inflation, but mostly because the “allocative effect” in which money would move from working class to rich and from people who did productive things to Wall Street.

[Bernanke is most notable for his 2007 statement: “We believe the effect of the troubles in the subprime sector on the broader housing market will likely be limited and we do not expect significant spillovers from the subprime market to the rest of the economy or to the financial system.”]

How does QE work?

The basic mechanics and goals of quantitative easing are actually pretty simple. It was a plan to inject trillions of newly created dollars into the banking system, at a moment when the banks had almost no incentive to save the money. The Fed would do this by using one of the most powerful tools it already had at its disposal: a very large group of financial traders in New York who were already buying and selling assets from the select group of twenty-four financial firms that were known as “primary dealers.” The primary dealers have special bank vaults at the Fed, called reserve accounts.II To execute quantitative easing, a trader at the New York Fed would call up one of the primary dealers, like JPMorgan Chase, and offer to buy $8 billion worth of Treasury bonds from the bank. JPMorgan would sell the Treasury bonds to the Fed trader. Then the Fed trader would hit a few keys and tell the Morgan banker to look inside their reserve account. Voila, the Fed had instantly created $8 billion out of thin air, in the reserve account, to complete the purchase. Morgan could, in turn, use this money to buy assets in the wider marketplace.

Bernanke’s initial goals were to create $600 billion via QE, with the justification that this would bring down unemployment. “Before the crisis [of 2008], it would have taken about sixty years to add that many dollars to the monetary base.”

The Fed’s own research on quantitative easing was surprisingly discouraging. If the Fed pumped $600 billion into the banking system, it was expected to cut the unemployment rate by just .03 percent.

Who had the best crystal ball?

Jeffrey Lacker, president of the Richmond Fed, said [in 2010] the justifications for quantitative easing were thin and the risks were large and uncertain. “Please count me in the nervous camp,” Lacker said. He warned that enacting the plan now, when there was no economic crisis at hand, would commit the Fed to near-permanent intervention as long as the unemployment rate was elevated. “As a result, people are likely to expect increasing monetary stimulus as long as the level of the unemployment rate is disappointing, and that’s likely to be true for a long, long time.”

[Richard] Fisher, the Dallas Fed president, said he was “deeply concerned” about the plan. Of course, he didn’t let pass the chance to use a nice metaphor: “Quantitative easing is like kudzu for market operators,” he said. “It grows and grows and it may be impossible to trim off once it takes root.” Fisher echoed Hoenig’s warnings that the plan would primarily benefit big banks and financial speculators, while punishing people who saved their money for retirement. “I see considerable risk in conducting policy with the consequence of transferring income from the poor, those most dependent on fixed income, and the saver to the rich,” he said.

What’s wrong with massive asset price inflation, as the Fed was trying to achieve? The author says that asset price bubbles are the typical drivers of both banking and market collapses. Example from the 1980s:

When Paul Volcker and the Fed doubled the cost of borrowing, the demand for loans slowed down, which in turn depressed the demand for assets like farmland and oil wells. The price of assets began to converge with the underlying value of the assets. The price of farmland fell by 27 percent in the early 1980s; of oil, from more than $120 to $25 by 1986. The collapse of asset prices created a cascading effect within the banking system. Assets like farmland and oil reserves had been used to underpin the value of bank loans, and those loans were themselves considered “assets” on the banks’ balance sheets. When land and oil prices fell, the entire system fell apart. Banks wrote down the value of their collateral and the reserves they were holding against default. At the very same moment, the farmers and oil drillers started having a hard time meeting their monthly payments. The value of crops and oil were falling, so they earned less money each month. The banks’ balance sheets, which once looked stable, began to corrode and falter.

This was the dynamic that so often gets lost in the discussion about the inflation of the 1970s and the collapse and recession of the 1980s. The Fed got credit for ending inflation, and for bailing out the solvent banks that survived it. But new research published many decades later showed that the Fed was also responsible for the whole disaster.

Why don’t people get nervous when an asset bubble is inflating?

When asset inflation gets out of hand, people don’t call it inflation. They call it a boom. Much of the asset inflation of the late 1990s was showing up in the stock market, where share prices were rising at a level that would have been horrifying if it was expressed in the price of butter or gasoline. The entire Standard & Poor’s stock index rose by 19.5 percent in 1999. The Nasdaq index, which measured technology stocks, jumped more than 80 percent.

When asset bubbles burst, the Fed is right there:

Over the next two years [after the dotcom crash of 2000], the Federal Reserve’s state of emergency became almost permanent. The rate cuts of 2001 remained in place, with the cost of short-term loans staying below 2 percent until the middle of 2004.

As with coronapanic, dramatic efforts for short-term relief lead to long-term disaster:

If there was one thing Hoenig had learned, it was that the Fed’s leaders, who were only human, tended to focus on short-term events and the headlines that surrounded them. But the Fed’s actions were expressed in the real world over the long term, after they had time to work their way through the financial system. When there was turmoil in the markets, the Fed leaders wanted to take immediate action, to do something. But their actions always played out over months or years and tended to affect the economy in unexpected ways.

The book was written before the Silicon Valley Bank collapse, but does this sound familiar?

The Fed was essentially coercing hedge funds, banks, and private equity firms to create debt and do it in riskier ways. The strategy was like a military pincer movement that closes in on the opponent from two sides—from one direction there was all this new cash, and from the other direction there were the low rates that punished anyone for saving that cash.

Before the financial collapse that started in 2007, the reward for saving money in a 10-year Treasury was 5 percent. By the autumn of 2011, the Fed helped push it down to about 2 percent.I The overall effect of ZIRP [zero-interest-rate policy] was to create a tidal wave of cash and a frantic search for any new place to invest it. The economists called this dynamic the “search for yield” or a “reach for yield,” a once-obscure term that became central to describing the American economy.

Then, as now, the nation’s problems started in San Francisco:

One of Bernanke’s secret weapons in the lobbying effort was his vice chairwoman, Janet Yellen, the former president of the San Francisco Fed. Yellen was an assertive and convincing surrogate for Bernanke, and she championed an expansive use of the Fed’s power.

“Janet was the strongest advocate for unlimited” quantitative easing, [Elizabeth] Duke recalled. “Janet would be very forceful. She is very confident, very strong in promoting the point of view.” Yellen and Bernanke were convincing, and their argument rested on a simple point. In the face of uncertainty, the Fed had to err on the side of action.

If it is any comfort, the Europeans are even dumber and more devoted to cheating with money instead of working harder than we are:

In Europe, the financial crisis of 2008 had never really ended [by 2012]. The debt overhang in Europe was simply astounding. Just three European banks had taken on so much debt before 2008 that their balance sheets amounted to 17 percent of the entire world’s GDP.

The PhD economists would bamboozle the governors with banking experience at FOMC meetings.

The meeting opened with a long presentation from two Fed staff economists that seemed designed to settle any doubts about the new round. The study was framed as a scientifically rigorous forecast of what another round of quantitative easing might do, and how long it would last. It used rigorous academic language and was full of precise measurements and graphs. But this presentation, for all its detail, was catastrophically wrong in virtually every important prediction that it made. Revealingly, the grave mistakes all pointed in the same direction. And it was a direction that would help Bernanke push his case.

What was the incentive for an individual economics Ph.D. to overestimate in this absurd manner?

Central banks around the world consistently misled themselves about the effects of quantitative easing. The banks overestimated QE’s positive impact on overall economic output, when compared against studies conducted by outside researchers, according to a 2020 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research. And central bank researchers who reported larger effects from quantitative easing tended to advance faster in their careers, the study found.

What happens when the Fed hints that a $750 billion QE program begin in 2013 might end?

Her heart sank as she watched the Treasury rates spike. It reflected an almost instantaneous wiping out of all the work the Fed had just done. So many billions had been pumped into the banking system to push down Treasury rates, and now the declines were disappearing. “At that point, it forced the Fed to be even more committed to continuing on,” she said. “The continuing of the purchases—there just kind of wasn’t any choice at that point. They had to continue, and had to bring reassurance to the market that they were going to continue.”

This market reaction was called the Taper Tantrum and the Fed ended up having to turn the $750 billion program into a $1.6 billion program.

I’ll do another post on the second half of The Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the American Economy. (Update: see Post #2 on The Lords of Easy Money (inflation and the Federal Reserve))

Meanwhile, let’s have a look at what’s on the San Francisco Fed’s home page.

The story about Black Resilience is inspiring, but why not a story about white resilience? I got some help from ChatGPT, which had no trouble understanding the concept of private profits combined with socialized losses:

Once upon a time, there was a white Silicon Valley Bank executive named Chip. He had always been a smooth talker, with a talent for making people trust him. He was charming, charismatic, and had a reputation for being a genius when it came to finance.

Chip was known for his connections to the wealthy elite of Silicon Valley. He had a group of rich white friends who were always looking for ways to invest their money. And Chip had just the thing for them – loans on favorable terms.

He knew that these loans were risky, but he was confident that he could make a big return for his investors and himself. And he did. Chip’s friends made a killing, and he earned a fortune for himself in the process.

But Chip’s greed didn’t stop there. He also enhanced short-term profits by not hedging against interest rate swings. This left the bank vulnerable to sudden changes in the market, but Chip didn’t care. He was only interested in making as much money as possible.

Unfortunately, Chip’s risky bets eventually caught up with him. The bank found itself in trouble, and it turned to the government for help.

The government decided to bail out the bank, using taxpayer money to cover its losses. The bailout cost the taxpayers $100 billion, a staggering sum that was hard for many people to comprehend.

But while the taxpayers were bleeding, Chip was retiring to his Napa winery, surrounded by the trappings of his wealth. He didn’t seem to care about the harm he had caused or the suffering he had inflicted on others.

Many people were outraged by Chip’s actions. They felt that he had taken advantage of the system, using his position of power to enrich himself and his friends while costing taxpayers billions of dollars.

But for Chip, it was all worth it. He had made a fortune, and he could now enjoy the fruits of his labor without a care in the world. And while the bank eventually recovered from the crisis, the memory of Chip’s actions lingered, a reminder of the dangers of greed and recklessness in the world of finance.

More:

Nerd news (unrelated, but of interest?): Gordon Moore, Intel co-founder dies, aged 94. ‘Impossible to imagine the world we live in today without his contributions’

https://www.theregister.com/2023/03/25/gordon_moore/

Somehow there are never huge celebrations for MIT PhD, war hero, transistor-inventor, and Silicon Valley founder https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Shockley !

Separately, not to take anything away from Gordon Moore, but I am not sure that his work made any difference to the trajectory of semiconductors or even microprocessors. He was not involved in the development of the transistor, did not invent the MOSFET, and did not invent the https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Integrated_circuit (though his Intel co-founder Robert Noyce is credited with a big advance in the IC world).

Just as in science (lowercase), the existence of an individual engineer or even a group of engineers seldom makes a difference. (In uppercase Science, however, a single person can throw children out of school for 12-18 months!)

The only people who are surprised by inflation, are the people working at the Fed whose high-paying job is to not be surprised by inflation.

Come on, Milton,

You can do better than that !

The byproduct of inflation targeting is it causes hyperinflation of everything else to offset the deflation of 1 thing. Honest inflation targeting would keep the maximum of all categories at 2% instead of the average of all categories.

philg wrote: “First, since this is a political book let’s look at the author’s background politics.”

Even the Washington Post review of the book had issues with his objectivity:

“The author is surely correct that many Americans view the Fed as an unelected power aligned with elites, perhaps contributing to the disaffection that exploded on Jan. 6, 2021. He might have explored their prejudices with more dispassion.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2022/01/21/inside-ideological-divide-between-feds-board-its-bankers/

Christopher Leonard also wrote

Kochland: The Secret History of Koch Industries and Corporate Power in America (2019)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kochland

Patrick: I think his level of hatred for Trump and Republicans in general, and respect for elite Science (as embodied by the CDC/Fauci) is about on par for a U.S. corporate journalist. Here’s his description of the blackest day in American history: “On January 6, 2021, thousands of violent extremists laid siege to the United States Capitol. … It was the most effective attack on American democracy since the Civil War, and it marked an entirely new level of volatility in American society.”

Example of his uncritical acceptance of Science: “The virus spread more quickly because many workers who got sick did not have paid sick leave, so they stayed on the job and infected others. … Restaurants, theaters, stores, and schools closed down, in order to slow the infection. But while they were closed, the federal government [run by Donald Trump] failed entirely to implement any kind of unified response to the virus. This failure left businesses and schools with a terrible choice in late spring: They could either reopen, with the pandemic worse than before, or remain shut.”

I.e., he accepts Science’s view that humans are smarter than viruses and that, therefore, with an appropriately Science-informed president (such as Dr. Joe Biden, MD/PhD), very few Americans, if any, would have been infected by SARS-CoV-2 or harmed by this non-Chinese virus. Like Socialism, lockdowns did not work because they weren’t implemented by today’s Democrats.

“[T]he federal government [run by Donald Trump] failed entirely to implement any kind of unified response to the virus.”

I can only support this assertion. The Pfizer/BioNTech announcement that their product is 90% successful in preventing covid infections came on the 9th of November 2020, while Moderna’s came on the 15th of November. Trump’s defeat on the 3rd of November must have unblocked the federal funding, unleashed the creative energies of the researchers and triggered “the unified response to the virus” that led to those astonishing successes 6 and 12 days later. Real warp speed.

Why did you bother reading the book and why besides the sunk cost did you decide to fill this blog’s valuable real estate with the author’s insights? The author does not seem to have any background relevant to what he is writing about — he is a journalist with a journalism degree from the U of Missouri –and the median Amazon star seems to say the book is a piece of nonsense.

jdc: He’s a NYT journalist so, as with the NYT, sometimes the facts printed are correct and interesting and the interpretation/spin bias is so predictable that it is easy to filter out. There do seem to be some absurd arithmetic errors in the book, which is interesting mostly as a window into the innumeracy of America’s elites. Here’s one that neither the author nor the editors questioned: “Robinhood might have organized all the trading through its app, but the trades were actually executed by companies like Citadel. These firms paid Robinhood millions of dollars for the privilege because it allowed them to see what people were buying, then make trades based on that information as they filled the order. This was called paying for order flow. Robinhood earned about $19,000 from trading firms for each dollar that a normal retail investor had in their account. Robinhood’s cash from order flow more than tripled from the start of 2020 to the same period in 2021.” If someone ACH’d $1,000 into a Robinhood account and purchased stock in Tesla, Robinhood immediately got paid $19 million?

I agree with jdc. The author exhibits profound ignorance of how the Federal Reserve works.

Ivan: Can you be more specific? In addition to some 2016-2019 efforts, the author describes spending a full year cowering at home studying the Fed and scribbling. Did he never manage to understand the basics?

Oh boy, where to start ?

“To execute quantitative easing, a trader at the New York Fed would call up one of the primary dealers, like JPMorgan Chase, and offer to buy $8 billion worth of Treasury bonds from the bank. JPMorgan would sell the Treasury bonds to the Fed trader. Then the Fed trader would hit a few keys and tell the Morgan banker to look inside their reserve account. Voila, the Fed had instantly created $8 billion out of thin air, in the reserve account, to complete the purchase. Morgan could, in turn, use this money to buy assets in the wider marketplace.”

That’s not how it works. In the first place, Morgan did not get richer: it merely swapped one asset for another which it most likely would swap for yet another. Otherwise why bother selling it in the first place ?.

In the second place, the Fed buys Treasuries on the *secondary* market at competitive prices from both JP Morgan and plumber Joe by soliciting offers from multiple primary dealers for each trade. A dealer can be punished (de-listed/fined, etc) for unreasonable or unfair pricing. Thus, JP Morgan cannot sell a bond at a price higher than plumber Joe. As a result of the transaction, the bond seller gets cash and the Fed the bond. Whether subsequent bond seller behavior will be inflationary depends on his life goals: plumber Joe may decide to expend his business and swap cash for tools and supplies or go on a cruise. Likewise a bank. There’s no difference for economy who sells the bond. Each of the potential players merely performs an asset swap intermediated eventually, via PDs, by the Fed or any other central bank.

The bond-for-cash transaction does result in an increase of reserve money which may have indirect inflationary effects on economy, mainly cheaper loans from banks. Or may not as largely happened during the 2008 QE exercise.

The chap has no clue about basic accounting and central bank operations and chooses instead to engage in conspiracy theories. Unfortunately, a lot of people follow the same easy conspirological path in explaining the Fed actions even though the latter’s raisons d’etre and means to achieve them are described in excruciating details on the Fed websites. I’d humbly propose that on encountering the words “printing money”, a Pavlovian reflex should kick in, and any book with such words should fly to a dustbin as a result.

That is not to say that the Feds are blameless or do not make mistakes. E.g. 2008 bank bailout, the SVB bailout, QE itself, etc. Hose cases are distinguishable, though, from the sinister and incorrect description of routine Fed operations.

I just stumbled over a pictorial presentation of the QE mechanics. Perhaps, it’ll help to clarify QE moving parts mechanics than the Fed website boring prose !

https://maroonmacro.substack.com/p/issue-7-quantitative-easing-and-the

Ivan’s example on QE was exactly the one that jumped out at me.

The correct description of QE is that they’re buying bonds in order to lower long-term rates.

This bit seems largely non-sensical:

“The basic mechanics and goals of quantitative easing are actually pretty simple. It was a plan to inject trillions of newly created dollars into the banking system, at a moment when the banks had almost no incentive to save the money.”

I think the problem is that he’s confusing a few separate things

– QE, which is bond-buying in order to move the long-term yield curve

– The Fed letting the banks post bonds to the Fed and get cash in return

– Congress putting cash into banks to improve their balance sheets.

But I have no idea where the “no incentive to save the money” part comes from.

It would be understandable for a common person to not know the difference, but if you’re going to write a book on a topic, gotta learn these basics.

@Ivan,

> Whether subsequent bond seller behavior will be inflationary depends on his life goals: plumber Joe may decide to expend his business and swap cash for tools and supplies or go on a cruise.

Go on a cruise is what 80% of the easy-money recipient do. Why? It’s human nature, 20% do the work of 80%. This is why the government cannot just “print money” as a way out of crises, any kind of crisis.

But, wait, George.

Your hypothetical is not realistic. If Joe the plumber wanted to go on a cruise, he would not have a bond to sell. Instead, he would have gone on a cruise upon receiving clients’ payments, why would he delay instant gratification ?

So, he saved money by buying a bond, and upon selling it he’ll most likely spend money on business expansion. Different sort of behavior would have been against his nature as a saver.

Even if he did decide, hell with it, I am going to enjoy my life, I am going on a cruise . In this scenario, he would have spent his *own* bond, without any handouts !

It is the Treasury that is in the business of handouts (fiscal “policy”), not the Feds (well, not directly, or not when doing something crazy like bailing out the SVB). These two entities are separate so far, regardless of what Mosler and his MMT pals may think about that.

Philip — What motivated you to read this book?

Seems like it has all the red flags — (1) writer with strong political bias, and (2) no expertise in the subject matter, (3) a .biz domain on his personal site (http://www.christopherleonard.biz)

These excerpts show he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

It does not matter if the author gets some of the basics wrong. He touches subjects that are currently classified as “right-wing” while garnishing them with approved thoughts to make the book palatable for the virtuous.

This is actually an excellent tactic. The Hoenig quote is certainly correct. This book should be given to Democrat friends as a gateway drug. They’ll believe an NYT journalist.

Regarding European incompetence. Yes, it’s bad, but some of it is by design. The Euro needs to be kept low so the corporations get rich from exports while the peasants have no purchasing power and cannot build wealth because of inflation.

4/2 is a 100% increase. 12/2 is a 500%, right?

Great point! Fixed in original post!