We recently visited the Glen Canyon Dam, which destroyed Glen Canyon and replaced it with a reservoir to hold surplus water in a river that doesn’t have any surpluses (calculations were made in the early 20th century, a period of remarkable wetness when compared to the previous 800 years). From the Carl Hayden Visitor Center:

(Is the visitor center named after a senior engineer who made the dam possible? One or more of the 18 workers who died so that the dam could live? No. It is named for a U.S. Senator who funneled tax dollars into this project.)

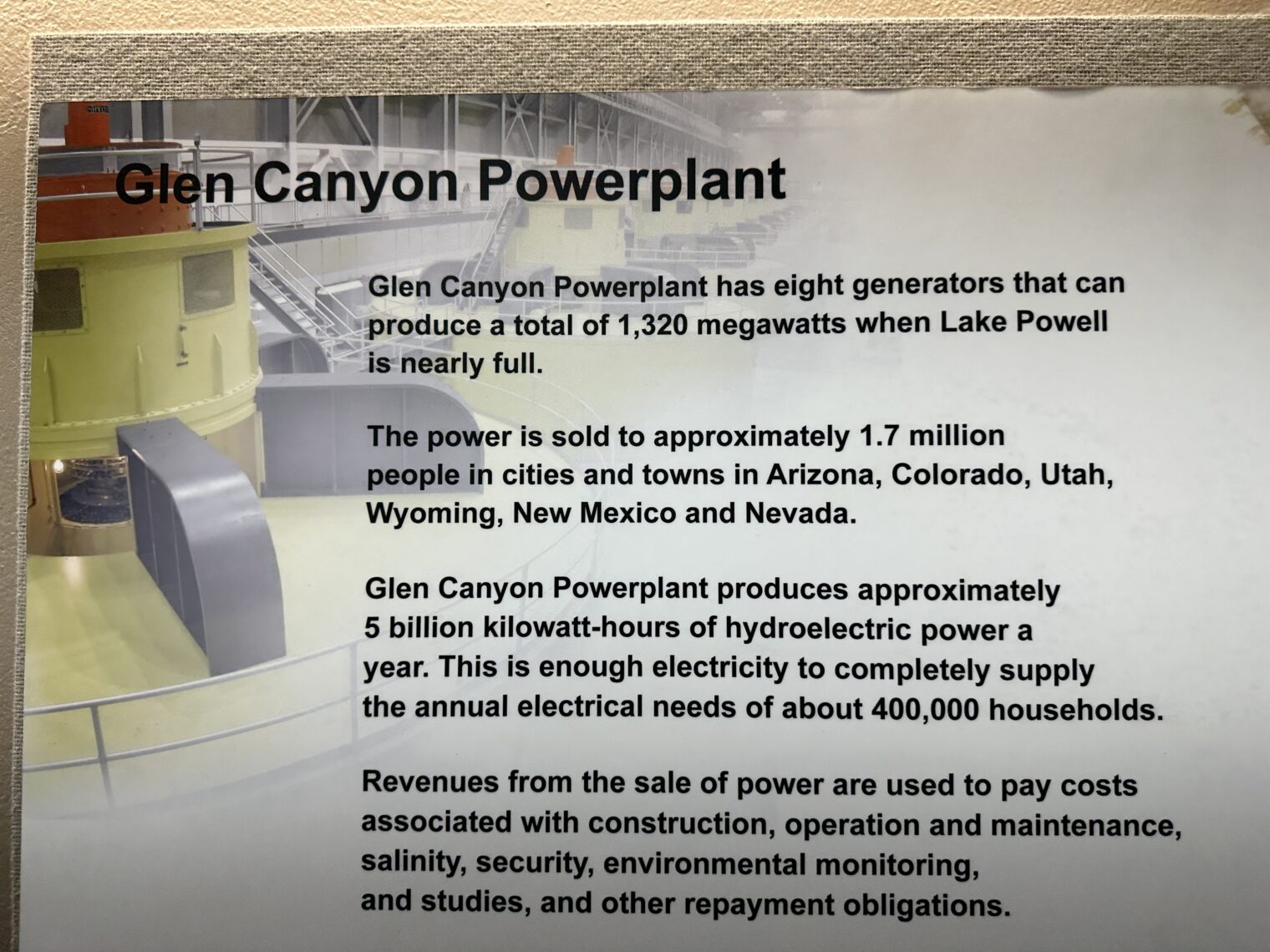

The dam powers 400,000 households, which means that the trashing of what would have easily qualified as a National Park does not generate enough power for the houses that are occupied by a single year of immigration into the U.S. What did this cost?

$2.17 billion in pre-Biden (2015) money. The BLS says that this is roughly $2.82 billion in Bidies. If we can arrange for God to give us a new raging river ever 3-6 months suitable for damming, in other words, we can provide clean hydropower to the new American households formed by migrants at a capital cost of $7,000 each.

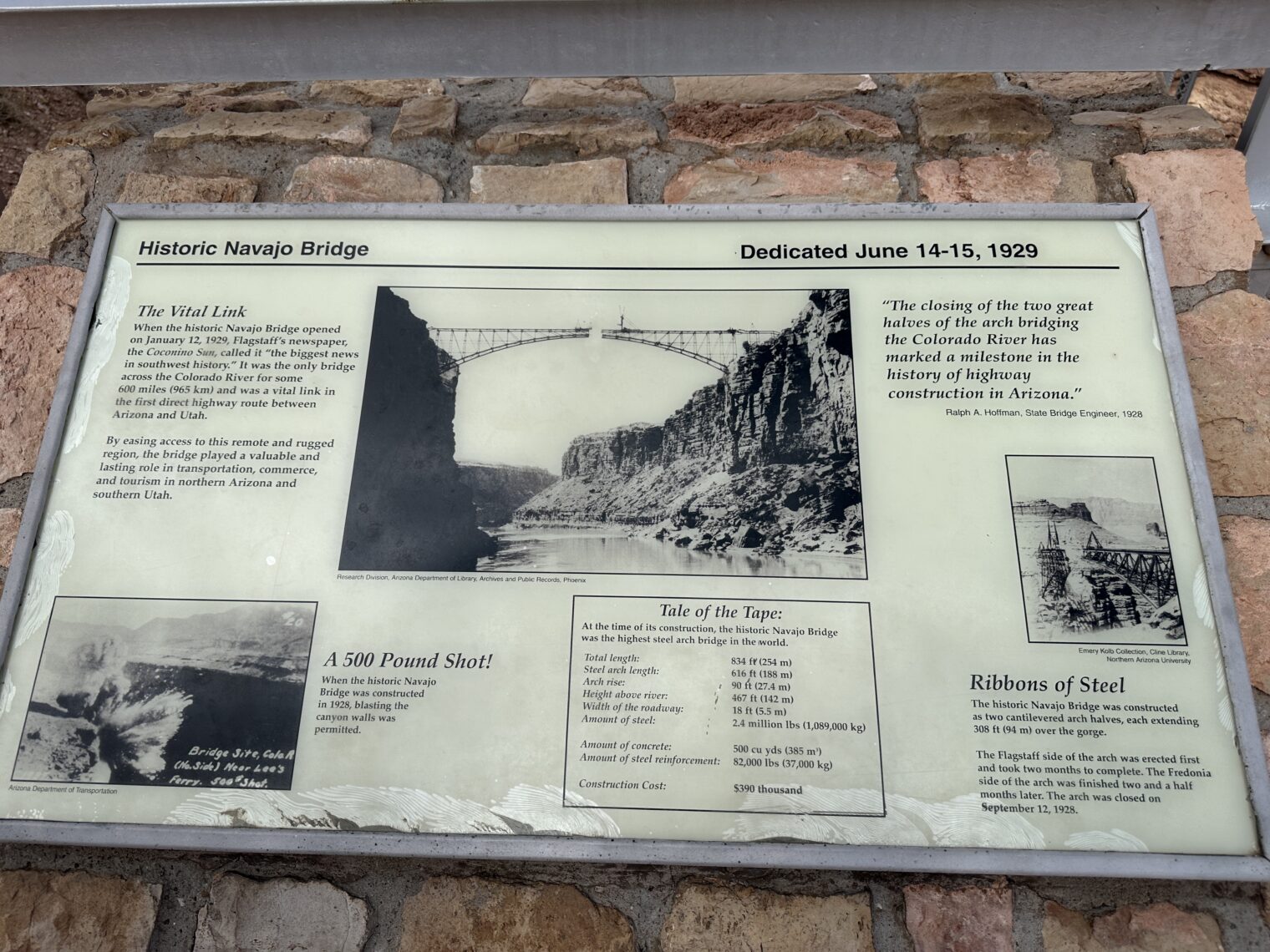

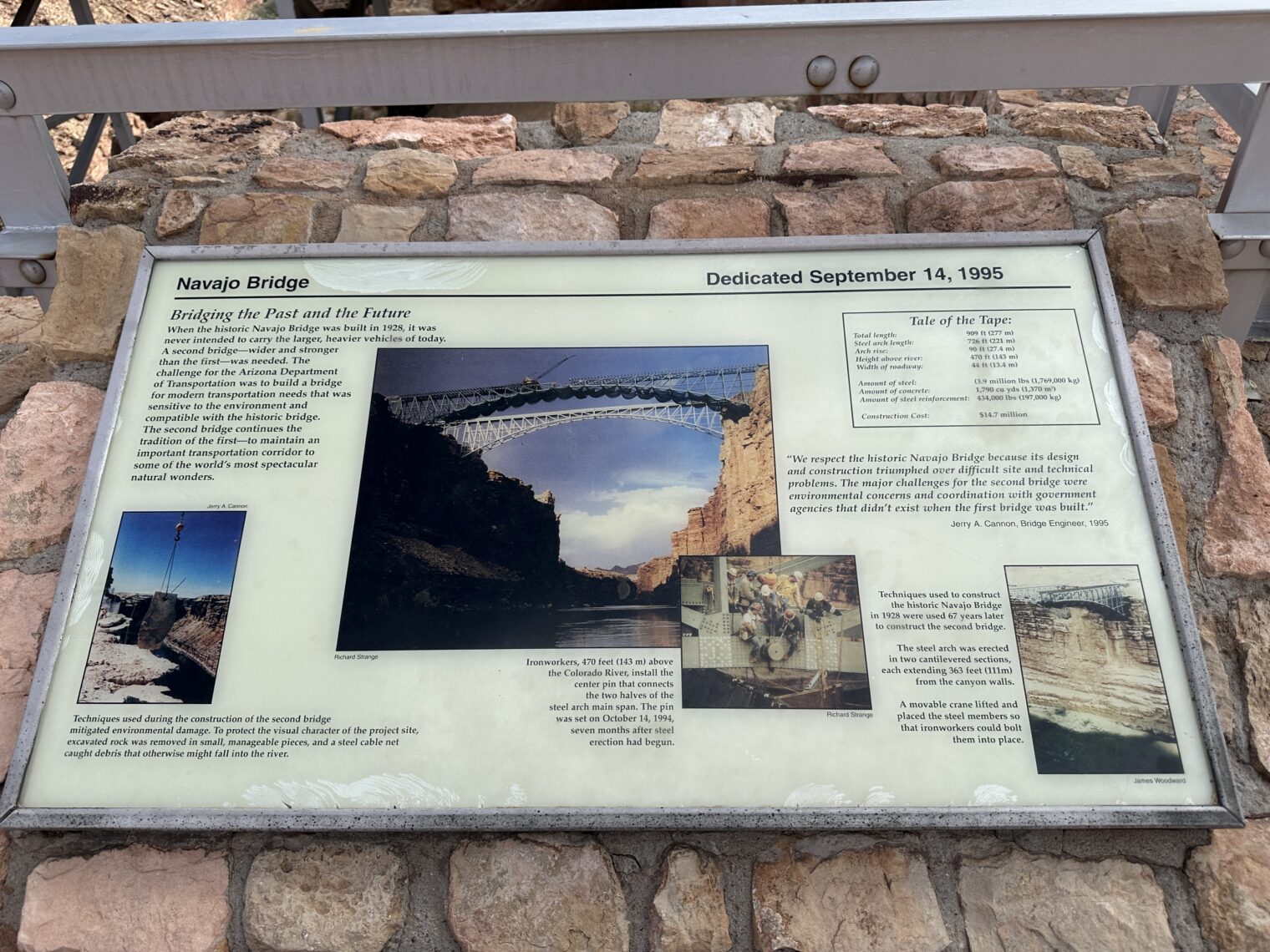

On the third hand, maybe it would cost us a lot more today to build a monster dam. At the Navajo Bridge, just downstream of the dam, the government notes that modern construction techniques are similar to what we used in 1929, but bureaucracy and regulation are dramatically more challenging:

How much inflation has there been in concrete-rich power-generating facilities? We can look at nuclear plant construction. This 2019 paper says that the cost has gone up about 10X, in constant dollars, compared to the 1970s (takes us twice as long as costs 5X as much per day). If we had help from God (new river ever 6 months), in other words, it would cost $70,000 per new household (see How much would an immigrant have to earn to defray the cost of added infrastructure?) to provision the power generation infrastructure.

(Comparison: progressive technocrats in California have spent $9.8 billion so far on their high-speed rail dream… without laying even one mile of track (CNBC).)

What would Glen Canyon look like if this massive silt-collecting dam hadn’t been built? Here’s the Horseshoe Bend, just downstream, photographed at 0.5X on the iPhone 14:

What does the dam look like?

A concrete salesman’s dream! Note that last bucket of concrete was poured in September 1963, the same year in which your beloved (I hope) blog host was born. The project was supposed to take 6.5 years, including all of the prep work and the bridge, but was finished after 6 years for substantially less than forecast (by Kiewit, whose Boston Harbor project was rendered lethal by government bureaucrats as described in Book review for Bostonians: Trapped Under the Sea).

Related:

- Department of Energy web page that says 6.2 percent of U.S. electricity is hydropower

If it really were 7000 bidies per person for 60 years, less then 120 annually or 10 bidies montly, it would make the power plant an equivalent of eternal engine. I bet on-going maintenance and production costs bring total costs multiple of this amount.

unrelated. Philip, you shared with us your commitment to become Portuguese citizen and asked advice for investing in Portugal. How are your investments going? Do they beat S&P 500 or some other benchmarks? What do you think about https://www.cnbc.com/2023/06/06/portugal-just-launched-a-government-funded-4-day-workweek-trial.html

The lion kingdom’s water supply Pardee dam was named after a governor. Surprised no dams have been named after Greenspun. If they didn’t secure the water rights when they did, Calif* would never have been developed & we’d all be packed into Boston or something.

I was in junior high school, and a member of the Angeles chapter of the Sierra Club, for the purpose of getting access to hiking activities, not for environmental reasons, when the soon-to-be-flooded Glen Canyon dam was under consideration. The Sierra Club put out an issue of their Sierra Club Bulletin, dedicated to a collection of amazingly gorgeous photos of the canyon.

Little Yosemite Valley was also flooded for a dam, and the Sierra Club agreed to that in exchange for some other concessions. During a visit to this Hetch Hetchy dam, about 20 years ago, I met a hiker about to go into the back country, and he had an interesting opinion. He felt that keeping tourists out of little Yosemite Valley resulted in the preservation of some amazing wilderness up there.

A Colorado environmental attorney named Steven Hannon wrote a novel called Glen Canyon, a really well done technological thriller. Unfortunately, it is no longer in print and there does not seem to be a Kindle version either.

> unfortunately, it is no longer in print

Perplexity.ai to the rescue: “summarize the novel ‘Glen canyon’ by Steve Hannon” …

> “Glen Canyon” by Steven Hannon is a novel that tells the story of a special place that was lost before the memory of most of us: Glen Canyon on the Colorado River. The novel is well-researched and paints a vivid picture of what was lost. The story follows three men’s river trip on the Colorado River through Glen Canyon, and their attempt to find a way to drain the reservoir without catastrophically rupturing the dam. The novel is 632 pages long and was published by Kokopelli in 1997.

Kevin Fedarko’s “The Emerald Mile” talks a lot about Glen Canyon Dam, the area, especially Page, and contains a fascinating account of how the dam was almost breached over the top in 1983 (saved by plywood). I learned a lot about cavitation and how powerful it can be. He’s one of my favorite writers, this book is absolutely incredible.

Eliot Porter’s “The Place No One Knew” (out of print, still available) has photos of Glen Canyon before it was flooded. No grand landscapes unfortunately, most are an intimate look at that place.

Here is Glen Canyon on Amazon.com ($65.70):

https://www.amazon.com/Glen-Canyon-Steven-M-Hannon/dp/0965512509/ref=mp_s_a_1_fkmr0_1?crid=1VBN5Y6MUXI97&keywords=glen+canyon+stephen+hannon&qid=1687627467&sprefix=%2Caps%2C188&sr=8-1-fkmr0