Just as the weather here in Palm Beach County turned perfect (dry and highs of 75-80), friends in Maskachusetts who’ve been talking about escape send me an article from the Manhattan-based Wall Street Journal, “Home Insurance Is So High in This Florida Town, Residents Are Leaving”:

James and Laura Molinari left Chicago for a two-story stucco home in this city’s historic Flamingo Park neighborhood. The four-bedroom house was a short bridge away from Palm Beach island and walking distance to downtown West Palm Beach.

Then the renewal for his home insurance arrived. The new rate for the year starting in September was around $121,000—more than seven times what the Molinaris said they paid last year, and more than 13 times what they paid when the family moved to Florida in 2019.

While they found a better rate from another insurer, at about $33,000 it is still nearly double what they paid last year. The family this month listed the home for sale with an asking price of nearly $3.5 million after determining that insurance costs made staying there too expensive. Others in Flamingo Park told The Wall Street Journal they are drawing the same conclusion.

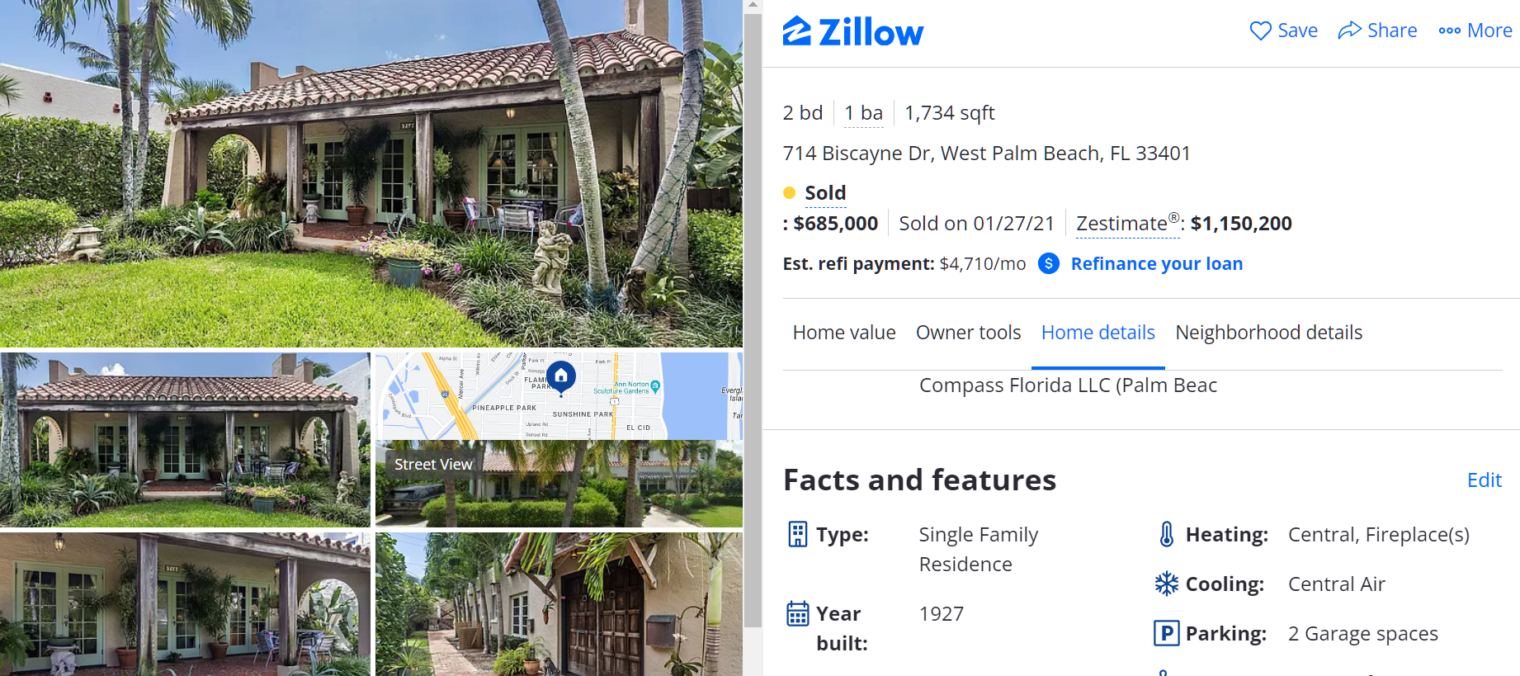

Paying nearly 1% of the house’s value for insurance is pretty expensive. But… “historic” in Florida? Here’s a house that I found on Zillow in that neighborhood:

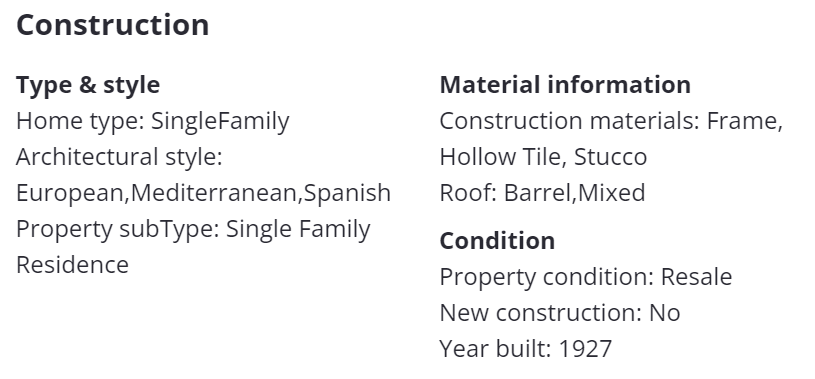

It’s almost 100 years old. Is it made from concrete blocks and steel rebar like the typical reasonably new house in Florida? No. It’s a wood structure (“frame”):

So the New York-based journalists write about a 100-year-old neighborhood with the implication that this is typical for Florida. In fact, any house built after Hurricane Andrew (1992; made landfall south of Miami as a Category 5 storm) is likely well-defended against hurricanes. State Farm won’t write new policies on houses built before 2003, presumably due to the fact that a post-Andrew building code took effect statewide in 2002 (a similar code took effect just two years after Andrew in South Florida).

More from the newspaper:

“When you have a home that’s one million dollars or less, your insurance premium becomes higher than your mortgage,” he said.

Can this be true? The article mentions a bunch of folks paying about 1 percent of their house+lot value to insure an ancient wooden structure. Absent a huge down payment or a savvy purchase just after the Collapse of 2008, wouldn’t a 30-year mortgage obtained in pre-Biden times have to be at least 2 percent of the house+lot value?

Separately, there doesn’t seem to be a huge effect yet from the new laws. “Here’s why Florida insurance premiums aren’t expected to go down anytime soon” (WTSP, October 12, 2023):

Karen Clark & Co’s analysis says that while there are factors beyond legislative control causing homeowner premiums to rise, recent laws targeting lawsuits against insurers might at least keep future premium hikes smaller than they might otherwise have been.

According to data, Florida had 10 times the percentage of litigated homeowner claims compared to other states where major hurricanes made landfall. On average, claims that are subject to lawsuits cost about seven times more on average than ones that aren’t. With new laws reducing the amount of insurance claims taken to court, one of the factors driving up future premium costs might be mitigated.

I’m wondering about the highlighted sentence. Is that adjusted for the severity of the damage to the house? It makes sense that a $10,000 problem doesn’t result in a lawsuit while a $100,000 problem might.

Circling back to the WSJ article… the only way to save money is to move back to the Northeast where the WSJ is based?

I read the WSJ article, and I did think that the costs it mentioned were too high. However, the cost of hurricane Ian in 2022 was $113 billion. That is a big loss for insurance companies. I suspect that insurers would offer different rates for each one of the dwellings of the “Three Little Pigs”, but if the total blow is more than $100 billion the rates must go up for everyone. Ian destroyed all the buildings on Sanibel and Captiva, where all constructed using old standards?

Insurers are leaving Florida, there must be a reason for that. Perhaps the article did exaggerate the problem, but there is no doubt that home insurance costs are significantly higher in Florida than almost any other state.

The implication [of the WSJ article] is that a new concrete house in Orlando has the same issues with insurance as a 100-year-old house close to the water.

No, I did not say that. I said that all homes are now paying more. I’m sure that there are big differences in rates among dwellings and insurance companies. It could be that insurance companies need to offer policies in all the state of Florida. If that is not the case, why they left? Why not keep offering policies in Orlando while leaving Sanibel? Or insuring just homes made of brick and mortar?

I also think that there could be other factors, besides the hurricane exposure, that drive up the cost of insurance in Florida. I looks like litigation costs are high in Florida. This is from a “USA Today” article: “During the last three years, 80% of property claim lawsuits in the country have been in Florida, compared to just 9% of the claims.”

https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/personalfinance/2023/07/19/florida-home-insurance-aaa-farmers-policy-reduction/70427062007/#:~:text=The%20litigation%20costs%20proved%20to,has%20in%20many%20other%20states.

“Dr” Phil:

I am especially frustrated by that 2002 building code change. It’s a gross intrusion into our freedumb by an overreaching gubment. All regulations are terrible — the common man has common sense!

Toucan?

Sam: Perhaps Mike has chosen to live in Colorado, which has no state building code (though, depending on the city/county, there may be a local code). https://www.durangoherald.com/articles/colorado-doesnt-have-a-statewide-building-code-would-enacting-one-help-protect-homes-against-wildf/

There are probably two downsides to a strict building code such as Florida’s.

The first is that people will develop a false sense of security. Humans can’t know what nature is capable of dishing out, even if Greta Thunberg’s words are studied carefully. Is a fortress on a barrier island built to the post-Andrew code invulnerable? A pre-Andrew house on a small hill in Orlando is likely safer!

The second is that housing becomes too expensive for the low-skill low-income people the U.S. has decided to invite in by the millions. A roof over one’s head is essential. A post-Andrew fortress is nice to have, but not essential, and it costs a lot more to build. Nobody wants to live in a shantytown, but the alternative is homelessness. If you have a growing population with a constant or falling skill level, resources become scarcer and people either have to be packed in more tightly (50 square feet per human?) or structures have to be constructed more cheaply. The problem with packing humans in tightly is that they can then be easily harvested by viruses such as SARS-CoV-2.

See

https://www.businessinsider.com/san-francisco-tiny-bed-pods-tech-not-up-to-code-2023-10

“People are getting bitchy but i’m not sure what for. i’m just trying to stay within the city of San Francisco without paying $4,000 a month or getting stabbed, and i think this is a great solution so far,” he wrote. “There’s a lot of cool people here too.”