A second post based on The Women Who Flew for Hitler, a book about Hanna Reitsch and Melitta von Stauffenberg. This supplies some detail about Hanna Reitsch’s pioneer flights in the world’s first practical helicopter.

One day [in September 1937], however, Karl Franke asked Hanna to fly him over to the Focke-Wulf factory at Bremen where he was due to take up one of the world’s first helicopters, the precarious-looking Focke-Wulf Fw 61, for a test flight. Professor Henrich Focke’s pioneering machine had overcome the two fundamental problems facing autogyro and helicopter designers: the asymmetric lift caused by the imbalance of power between the advancing and retreating ‘air-listing screws’, or rotor blades, and the tendency for the helicopter’s body to rotate in the opposite direction to its rotors. The solution was to use two three-bladed rotors, turning in opposite directions, which were fixed up on outriggers, like small scaffolding towers, in place of wings. An open cockpit sat below. It was not an elegant design; some papers described it as looking ‘like a cross between a windmill and a bicycle’, but it worked. According to Hanna, when she landed at Bremen with Karl Franke, Focke wrongly assumed that she was there to give him a second opinion. Seeing that she was ‘brimming with joy’ at the thought of taking the helicopter up, Franke was generous enough not to disabuse the great designer. Franke flew the machine first, as a precaution keeping it tethered to the ground by a few yards of rope. Unfortunately this also trapped him in reflected turbulence, buffeting the helicopter about. Such an anchor did not appeal to Hanna. Before she took her turn she had the rope disconnected and a simple white circle painted on the ground around the machine to guide her. As Hanna later recounted the story, with typical lack of false modesty, ‘within three minutes, I had it’. From now on Franke would argue that, in Germany, Hanna and Udet were the ‘only two people who were divinely gifted flyers’. The Fw 61’s vertical ascent to 300 feet, ‘like an express elevator’, with its noisy mechanical rotors literally pulling the machine up through the air, was completely different from the long tows needed by gliders, or even the shorter runs required to generate lift by engine-powered planes. To Hanna it was like flying in a new dimension. Despite the heavy vibrations that shook the whole airframe as she slowly opened the throttle, the revolutionary control of her position in the airspace at once fascinated and thrilled her, while the machine’s sensitivity and manoeuvrability was ‘intoxicating!’ ‘I thought of the lark,’ she wrote, ‘so light and small of wing, hovering over the summer fields.’ Hanna had become the first woman in the world to fly a helicopter.

(the above section is extensively referenced)

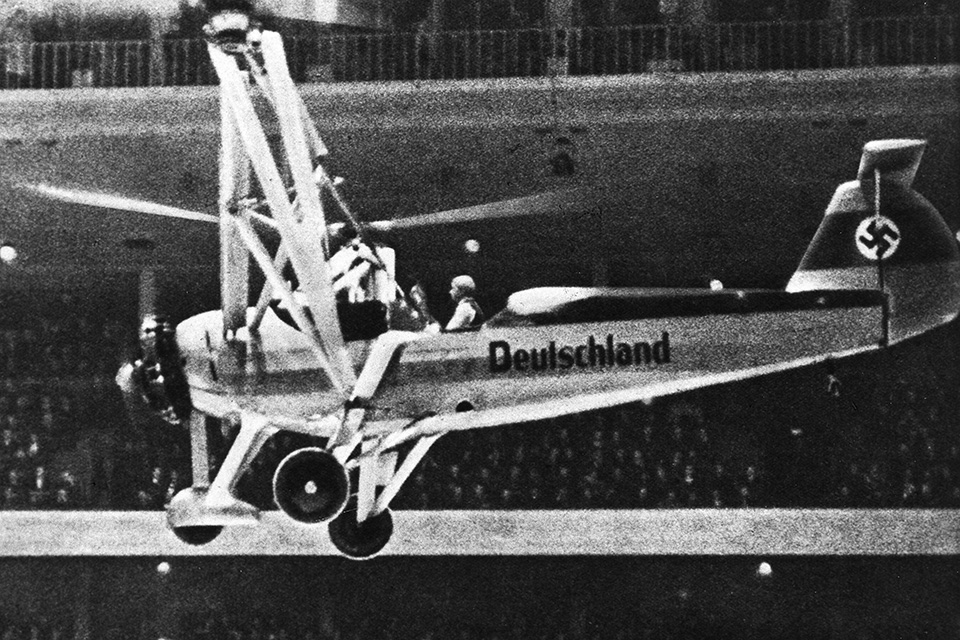

That February [1938], Germany was showcasing a range of Mercedes-Benz sports cars as well as revealing plans for the forthcoming ‘Volkswagen’ to an international audience at the prestigious Berlin Motor Show. ‘The story of the Berlin exhibition since National Socialism came to power,’ the national press fawned, ‘has been an uninterrupted triumph.’ Hitler wanted to use the 1938 show as more than a trade fair. It was to be a demonstration of German engineering excellence for unprecedented numbers of visitors. For this he needed a star attraction. Hanna was booked to head the programme: she was to be the first person in the world to fly a helicopter inside a building. The theme of the motor show was Germany’s lost colonies: ‘at that time a much ventilated grievance’, Hanna noted. In preparation, the great Deutschlandhalle sports stadium, then the world’s largest arena, had been furnished with palm trees, flamingos, a carpet of sand and, in Hanna’s words, ‘a Negro village and other exotic paraphernalia’. This was the scene she was to rise above in the Focke-Wulf Fw 61 helicopter: a symbol of German power and control. At first Hanna was scheduled to make only the inaugural flight, after which the chief Focke-Wulf pilot, Karl Bode, was to take over. During a demonstration for Luftwaffe generals, however, knowing that the helicopter’s sensitivity meant any slight miscalculation could take him sweeping into the audience, Bode refused to risk rising more than a few feet above the ground. It was safe, but hardly impressive enough for the crowds who would be looking down from the galleries of steeply tiered seating. Then, through no fault of Bode’s, one of the propellers broke. ‘It was dreadful,’ Hanna told Elly. ‘There were splinters from the rotor blade flying around and the flamingos were all creating.’9 Once the blades had been replaced, Hanna took her turn. With typical insouciance, she lifted the helicopter well above the recommended height and hovered in the gods. Göring quickly ordered that she was to make all the motor show flights. Bode never forgave her.

It turns out that the public back then didn’t love watching helicopters any more than they do now:

But when Hanna revved up the rotors [inside the stadium] she was horrified to discover that the machine refused to lift. The reputation of the Reich, her own career and, Hanna must have realized, possibly even her liberty, hung stuttering in the spotlights just a few inches above the floor. Surrounding her, watching every manoeuvre of both machine and pilot through a growing cloud of dirt and sand, were some 8,000 spectators, including many representatives of the international press. Hanna was certain that the problem was caused by the helicopter’s normally aspirated engine being starved of air by the breathing of the vast audience. Painful minutes passed while the technicians debated, but then the great hall’s doors were opened. Hanna and the Deutschland immediately ‘shot up to about twenty feet’ and slowly rotated on the spot. At first ‘the audience followed the flight intently’, but such a controlled display held little drama and the applause grew desultory. At the end of the demonstration Hanna neatly lowered the machine with her head held high, executed a perfectly timed, stiff-armed Nazi salute, and landed safely on her mark. She had practised this countless times for Udet while he sat comfortably ensconced in an armchair, puffing at a cigar.

(Maybe opening the doors reduced the temperature and, therefore, the density altitude?)

I had always thought that Hanna was the world’s first female jet pilot, but the book says that she likely never flew the Me 163 under power. (It’s actually a rocket-powered plane, but that’s close enough.) Her job was to test fly it in glider mode, which was how every flight in the plane ended. Nazi leadership did not want their star female pilot to be killed by the Me 163:

… the famous Me 163b Komet, was powered by extremely combustible twin fuels kept in tanks behind, and on either side of, the pilot’s seat. The fuels were a mixture of methanol alcohol, known as C-Stoff, and a hydrogen peroxide mixture, or T-Stoff. Just a few drops together could cause a violent reaction, so they were automatically injected into the plane’s combustion chamber through nozzles, where they ignited spontaneously producing a temperature of 1,800°C. Several test planes with unspent fuel blew up on touchdown. ‘If it had as much as half a cup of fuel left in its tank,’ one pilot reported, ‘it would blow itself into confetti, and the pilot with it.’ Several simply exploded in the air. Hydrogen peroxide alone was capable of spontaneous combustion when it came into contact with any organic material such as clothing, or a pilot. To protect themselves, test pilots wore specially developed white suits made from acid-resistant material, along with fur-lined boots, gauntlets and a helmet. Nevertheless, at least one pilot would be dissolved alive, after the T-Stoff feed-line became dislodged and the murderous fuels leaked into the cockpit where they seeped through the seams of his protective overalls. ‘His entire right arm had been dissolved by T-Agent. It just simply wasn’t there. There was nothing more left in the sleeve,’ the chief flight engineer reported. ‘The other arm, as well as the head, was nothing more than a mass of soft jelly.’

Hanna wasn’t scared by these deaths and injuries and tried to get into the powered test program. She was seriously injured even without the deadly fuel/engine:

Her Me 163b V5, carrying water ballast in place of fuel, was towed into the air behind a heavy twin-engined Me 110 fighter. But when Hanna came to release the undercarriage, the whole plane started to shudder violently. To make matters worse, her radio connection was also ‘kaput’.83 Red Very lights curving up towards her from below warned her something was seriously wrong. Unable to contact her tow-plane, she saw the observer signalling urgently with a white cloth, and noticed the pilot repeatedly dropping and raising his machine’s undercarriage. Clearly her own undercarriage had failed to jettison.

Hanna could have bailed out, but chose to try to preserve the airplane. She paid for this decision:

Hanna had fractured her skull in four places, broken both cheekbones, split her upper jaw, severely bruised her brain and, as one pilot put it, ‘completely wiped her nose off her face’.87 She had also broken several vertebrae. She was rushed to surgery but, knowing her arrival would cause a sensation, she insisted on travelling by car rather than ambulance, and on walking into the hospital through the quieter back entrance and up a flight of stairs before any members of staff were alerted.

In case you were tempted to complain about your own health woes:

Hanna spent five long months in hospital. After her condition stabilized, a series of pioneering operations included surgery to give her a new nose. Although she would always have a faint scar, and people who met her noted it was ‘evident something had happened there’, the reconstruction work was excellent.

Still suffering from headaches and severe giddiness, her first priority was to recover her sense of balance, without which she knew she could not fly. The summerhouse had a flight of narrow steps running from the ground up to the steep, gabled roof. Hanna climbed them cautiously until she could sit astride the ridge of the roof with her arms firmly clinging to the chimneystack, and look around without losing her balance. After a few weeks her vertigo began to ebb and she risked letting go of the chimney. Within a month, through pure determination, she could ease herself along the entire length of the ridge without feeling giddy. She built up her strength by walking, then hiking, through the forest. Despite setbacks and some despondency, in time she began to climb the pines, branch by branch, ruefully recalling the days of her childhood when ‘no tree had been too high’.

She was cleared to return to flying.

More: Read The Women Who Flew for Hitler.

Was that Comet saved? I think any insurance would consider it totalled, based on the injures. Looks like nazis had WWI – era metalforming technologies, when I was a child, my friends built safer contraptions on the streets.

I read that pioneering metallurgical technologies were developed by a German Jewish metallurgist who escaped the nazis and made his work available to the allies. I hope that Hannah’s migranes were not too bad after the crash.

Comet was pretty slow rocketplane. Nazis had also real jets, both ME and Heinkel. Messershmidt was choosen over HE. Probably due to favoritism, ME jet was a little faster then late WWII allied figter planes and too had to glide for landing. Soviet fighters scored some air victories over ME jets, and liked to stock them when they were about to glide for landing.

Me 262, a jet fighter, was treated the same way, despite oficially having flying range of 40 or so minutes, on par with other ww2 fighters.

Komet Me 163 considered to be effective against allied bomber formations, despite being often junked on landing.

Guess they didn’t have to coerce pilots into flying the Me 163, despite its tendency to kill them. Allies just waited 7 minutes for it to run out of fuel & then shot it down.