I recently finished Apple in China: The Capture of the World’s Greatest Company by Patrick McGee, a former reporter for the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times. What’s the scale of what Apple does in China?

The CHIPS and Science Act, which is designed to stimulate computer chip fabrication in America, will cost the US government $52 billion over four years—$3 billion shy of what Apple invested annually in China nearly a decade earlier. Let me underscore this point: Apple’s investments in China, every year for the past decade, are at least quadruple the amount the US commerce secretary considered a once-in-a-generation investment.

What’s the scale of Apple?

The number of Apple devices in active use surpassed 2.35 billion in 2025, led by 1.4 billion iPhone users who spend more than four hours a day immersed in their glowing screens. These users represent the richest quintile of people in the world, and Apple can advertise or promote features to them—wireless payment, television shows, music streaming, fitness offerings—for free. In fact, Google pays Apple close to $20 billion a year just to be the default search engine on the iPhone. The control Apple has over its ecosystem is extraordinary: When in 2021 Apple changed how third parties like Instagram and Facebook could “track users”—ostensibly a move to protect the privacy of iPhone owners—Meta estimated the new policy diminished its annual earnings by $10 billion. Meanwhile, revenue from Apple’s own privacy-first ad business was on a path to grow from $1 billion in 2020 to $30 billion by 2026. One advertising executive characterized the change as going “from playing in the minor leagues to winning the World Series in the span of half a year.” On average, Apple’s Services business earns margins north of 70 percent, double that of its hardware, and the business has been growing at nearly 20 percent a year for six years—all before potentially being supercharged by new artificial intelligence features. In short, the notion that Apple is at its peak is patent nonsense. But there is one Achilles’ heel: The fate of all the company’s hardware production relies on the good graces of America’s largest rival.

Don’t take the tech reporting here as gospel. The author has fallen in love with his subject:

The second force was the advanced nature of the Macintosh operating system (OS). It really was a decade ahead of its time when, in 1984, a boyish and handsome Steve Jobs, then just twenty-eight, unveiled the Mac with dramatic flair to a packed auditorium. When Jobs clicked the mouse—itself a novelty at the time—the computer took the air out of the room by speaking.

(The mouse, of course, was 16 years old in 1984. The graphical user interface, as embodied in the Xerox Alto, was 11 years old.)

The seeds of the App Store, in which Apple would take a cut of all sales, were sown circa 1980:

By the end of 1983, the Apple II “had the largest library of programs of any microcomputer on the market—just over two thousand—meaning that its users could interact with the fullest range of possibilities in the microcomputing world.” But Jobs resented third-party developers as freeloaders. In early 1980, he had a conversation with Mike Markkula, Apple’s chairman, where the two expressed their frustration at the rise of hardware and software groups building businesses around the Apple II. They asked each other: “Why should we allow people to make money off of us? Off of our innovations?” An attendee of the meeting would recount, years later, that Apple began to “fight” all third-party development.

The book is strong on recounting the rise of contract manufacturing in the 1980s and 1990s and on the history of Foxconn:

Foxconn had the humblest of origins. In 1974, two years before Apple was started out of a garage, twenty-three-year-old Terry Gou founded Hon Hai Plastics out of a shed. Gou, who’d just completed his duty in the Taiwanese army, founded the company with $7,500.

As the PC revolution took off in the early 1980s, Gou got in on the ground floor and created a name for himself making reliable sockets and connectors—small components that facilitate communication between different parts of a computer. The conn in Foxconn—Hon Hai’s international name—refers to connectors. “Fox” is just an animal he likes.

Employees were given a Little Red Book featuring the sayings of Terry Gou, some of which were also plastered on the otherwise bare walls. The aphorisms ranged from inspirational to threatening. “Work hard on the job today or work hard to find a job tomorrow,” said one.

In 1999, it was a company with $1.8 billion of revenue, far smaller than Solectron, SCI, or Flextronics, its US rivals. By 2010, Foxconn revenues were $98 billion, more than those of its five biggest competitors combined. And Foxconn’s extraordinary growth in those eleven years is the consequence of one client more than any other: Apple.

How much did China grow along with Foxconn?

By the time Mao died in 1976, China was poorer than sub-Saharan Africa. … In just twenty-five years, Shenzhen’s population grew a hundredfold.

Europe is poor compared to the U.S. Why not assemble stuff in Europe?

Once the Shenzhen line for iMacs was up and running, Foxconn established sites on two other continents. In Europe, Foxconn executive Jim Chang found a Soviet-era electronics site in Pardubice, a city of 100,000 people sixty miles east of Prague. The site had previously been run by a state-owned company called Tesla, whose specialty was radar systems and whose biggest client had been the government of Iran. The site had an eerie feel to it, like it had been hit by a neutron bomb. Forklifts stood motionless on the floor and cups of tea, their contents long gone cold, had been left on the tables. In May 2000, Foxconn was able to buy the plant for just 102 million CSK (2.9 million), a fire-sale price because it was bringing in jobs. Foxconn also won from the government a ten-year tax holiday.

The experience in the Czech Republic was an important proving ground for Foxconn and its hub model, but what it really demonstrated was that producing hardware in China was cheaper, more efficient, and less subject to media scrutiny. In China, assembly got done at incredible speed and with few complaints. Workers did twelve-hour shifts and lived nearby in dorms. At the Czech site, workers put in fewer hours and were represented by a trade union; they protested conditions and spoke to the press. Plans to build dormitories met local criticism and were abandoned. Over the course of a decade, Foxconn expanded its work in the Czech Republic, continuing to build for Apple, adding another location, and taking on production for Hewlett-Packard, Sony, and Cisco.

At one point, according to an ex-worker named Andrea, workers making Apple products didn’t receive an annual bonus as they were promised, so they threatened a “strike emergency” just before the ramp-up ahead of Christmas. “Afraid,” the Foxconn managers deposited the bonuses within a week. The incident triggered an audit by Apple, which interviewed workers about their experience. Apple, Andrea said, advocated for better conditions, but “instead Foxconn closed the division within half a year and 330 people were dismissed.” Around the same time, in August 2009, Foxconn shut its Fullerton site, too. How Foxconn laid the Czech workers off is worth highlighting. Mass dismissals—defined as laying off more than thirty people—need to be reported to the Labor Office, but it was important for Foxconn to avoid scrutiny. “What Foxconn did is they dismissed twenty-nine workers every month,” Andrea said. “Each month, regularly, they fired twenty-nine people.” The threat of a single strike ended all large-scale Apple assembly in Europe.

China ended up being the only answer for Apple and pretty much everyone else in the electronics world.

… by 2005, Jobs grasped that there was no going back. That year, a subordinate suggested that a certain project be done in the United States, and Jobs responded curtly. “I tried it. It didn’t work.” The results—in volume, efficiency, and price—were unmatched.

I’ll write more about this book in subsequent posts.

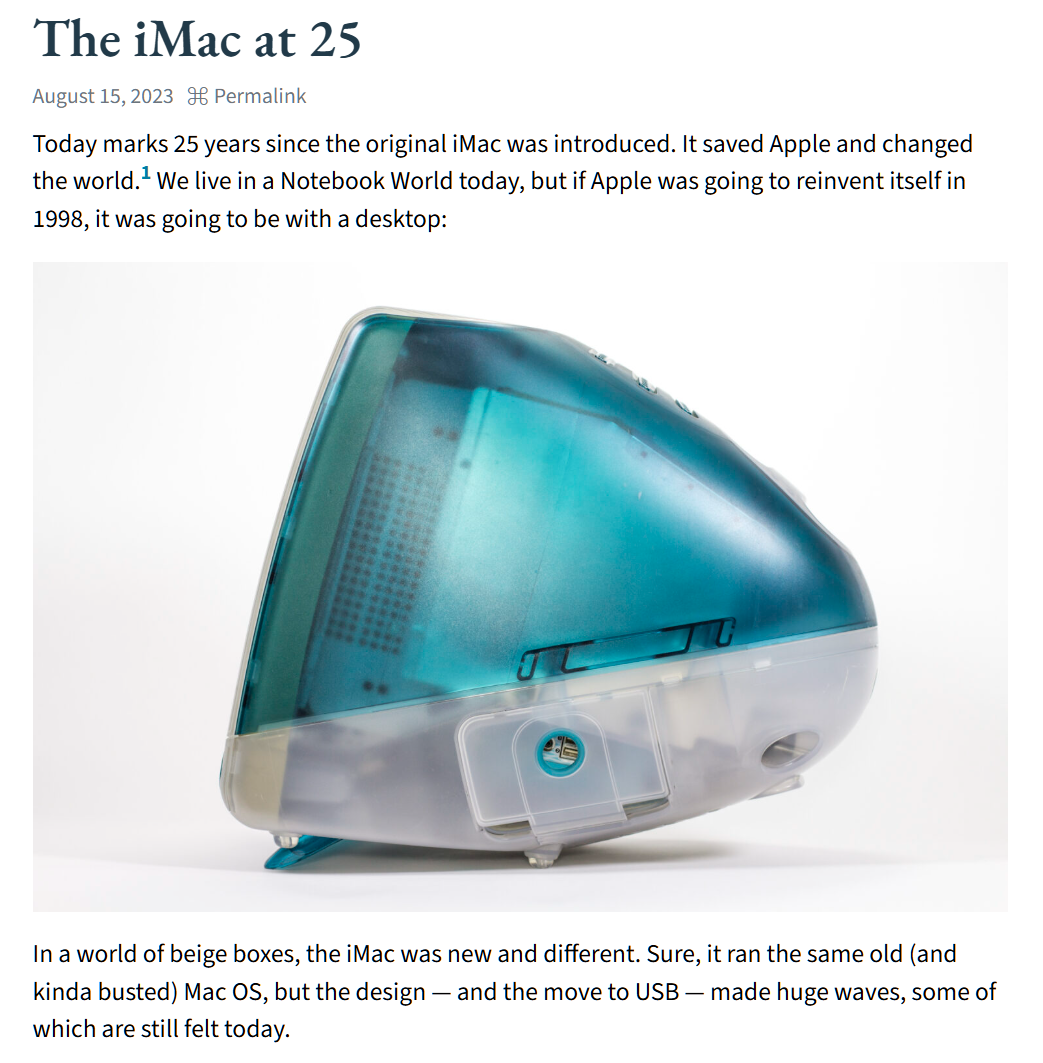

Reminder of what was considered attractive at the time Apple moved manufacturing offshore (source):

I’ve read the book; it is brilliant. For me, the key takeaway is that with substantial assistance from Apple, China now has a manufacturing ecosystem that has never existed in history. No other country — India, Vietnam, Mexico certainly not the US — will be able to match its integrated facilities in the next 25 years. Over 1000 parts are used in an iPhone, and Apple makes almost 1 million iPhones a day. Other than China, what companies could deliver 1 million parts a day to Apple, particulary at the quality levels that Apple demands.

Twenty-five years ago, China was a baby cub — cute and harmless. Now it is a ferocious tiger that if we mess with it too much, may try to eat us. We have to deal with that reality, particularly if fathers want to give their daughters two dozen toys on Christmas. We need to deal with reality rather than a pretend world, which means we need a President and Cabinet with a brain.

James: You say “we need a President and Cabinet with a brain” yet nearly all of the building up of Chinese capabilities described in the book occurred during the Obama administration. We are informed that Barack Obama and his cabinet were the smartest people ever to spend time in Washington, D.C.

I like Android phones built by Korean manufacturers. I think that they have most of the world market. Are they too assembled by Foxcon in China using China-built components? If not them Apple China magic is already replicated. What about HP and Dell laptops? They are all made in China as well.

Competing with a country like China is an almost impossible task. Here’s why:

1) Massive Workforce: With a population exceeding 1.4 billion, even if only one-tenth is actively engaged in the workforce, the sheer volume of available labor is staggering.

2) Low Labor Costs: A significant portion of the population lives on modest incomes, which means that almost any employment opportunity is considered valuable. This makes labor both abundant and inexpensive.

3) Centralized Government Control: China operates under a single-party system that exerts complete control over the economy, including regulation of the labor force and private enterprises. The government has the final say in nearly every aspect of economic activity.

4) Strategic State Support: The government actively supports and inflates key industries. It can do this because unlike many Western nations, China’s combined spending on healthcare, welfare, and the military is less than 15% of its GDP, allowing more resources to be funneled into economic development and industrial growth.

5) Cultural and Ethnic: Over 90% of China’s population is Han Chinese. This relative cultural and ethnic commonality can contribute to a more cohesive national identity and stable governance compared to nations with significant internal divisions.

6) Abundant Natural Resources: China’s vast landmass provides access to a wide range of natural resources, supporting industrial growth, infrastructure projects, and long-term development without heavy dependence on foreign supply chains. Oil is the primary resource China has a dependency on and that is widely available world wide.

In contrast, while other regions such as India or parts of Africa also offer large populations and low labor costs, they often struggle with ethnic diversity, political corruption, and government instability, factors that hurts long-term societal and economic stability.

Finally, Western societies have become accustomed to cheap goods, largely due to corporations constantly seeking ways to cut costs through outsourcing and globalization. As a result, when the price of even basic locally produced items, such as eggs increases, there is immediate public outcry and demand for explanations. Beyond the dependence on convenience and a comfortable lifestyle, many in the West have also grown used to government-provided benefits and increasingly expect more, further deepening this sense of entitlement with fewer hours to work.

Thus, expecting to compete with China is unrealistic. The only viable path would be a unified and coordinated effort by all developed nations to collectively counterbalance China’s economic dominance. Unfortunately, such global unity is unlikely. Trump’s tariffs may have done the job *if* he had first built a broad international coalition and persuaded all developed nations to implement similar measures. This too is an impossible task.