As noted in Reagan National Airport Black Hawk-CRJ crash, the easiest way to have prevented the January 2025 crash would have been to implemented congestion pricing on the highways around DC so that officials didn’t need helicopter taxi service to avoid the traffic jams that have been caused by dramatic population growth induced by spectacular growth in government spending (plus open borders?).

“The Last Flight of PAT 25 Two Army helicopter pilots went on an ill-conceived training mission. Within two hours, 67 people were dead.” (New York Magazine):

Black Hawks are typically flown by two pilots. The pilot in command, or PIC, sits in the right-hand seat. Tonight, that role was filled by 39-year-old chief warrant officer Andrew Eaves. Warrant officers rank between enlisted personnel and commissioned officers; it’s the warrant officers who carry out the lion’s share of a unit’s operational flying. When not flying VIPs, Eaves served as a flight instructor and a check pilot, providing periodic evaluation of the skills of other pilots. A native of Mississippi, he had 968 hours of flight experience and was considered a solid pilot by others in the unit.

In terms of flying hours, Mr. Eaves was at the same stage as a civilian helicopter pilot beginning a second year working as an instruction in little Robinsons, mostly going in circles around a training airport.

His mission was to give a check ride to Captain Rebecca Lobach, the pilot sitting in the left-hand seat. Lobach was a staff officer, meaning that her main role in the battalion was managerial. Nevertheless, she was expected to maintain her pilot qualifications and, to do so, had to undergo a number of annual proficiency checks. Tonight’s three-hour flight was intended to get Lobach her annual sign-off for basic flying skills and for the use of night-vision goggles, or NVGs. To accommodate that, the flight was taking off an hour and 20 minutes after sunset. …

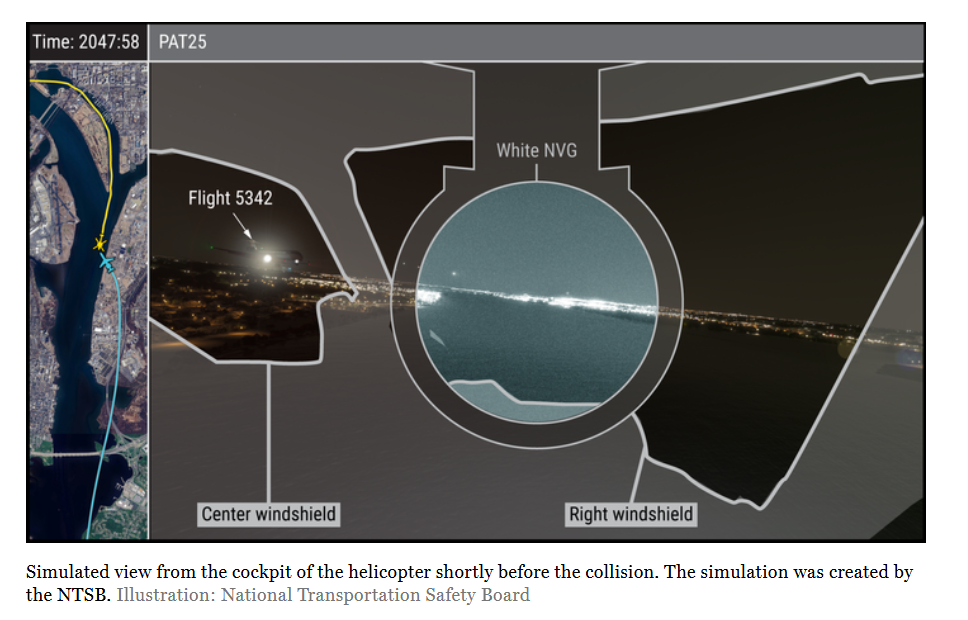

Night-vision goggles have a narrow field of view, just 40 degrees compared to the 200-degree range of normal vision, which makes it harder for pilots to maintain full situational awareness. They have to pay attention to obstacles and other aircraft outside the window, and they also have to keep track of what the gauges on the panel in front them are saying: how fast they’re going, for instance, and how high. There’s a lot to process, and time is of the essence when you’re zooming along at 120 mph while lower than the tops of nearby buildings. To help with situational awareness, Eaves and Lobach were accompanied by a crew chief, Staff Sergeant Ryan O’Hara, sitting in a seat just behind the cockpit, where he would be able to help keep an eye out for trouble.

Lobach, 28, had been a pilot for four years. She’d been an ROTC cadet at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which she graduated from in 2019. Both her parents were doctors; she’d dreamed of a medical career but eventually realized that she couldn’t pursue one in the Army. According to her roommate, “She did not have a huge, massive passion” for aviation but chose it because it was the closest she could get to practicing medicine, under the circumstances. “She badly wanted to be a Black Hawk pilot because she wanted to be a medevac unit,” he told NTSB investigators. After she completed flight training at Fort Rucker, she was stationed at Fort Belvoir, where she joined the 12th Aviation Battalion and was put in charge of the oil-and-lubricants unit.

In addition to her official duties, Lobach served as a volunteer social liaison at the White House, where she regularly represented the Army at Medal of Honor ceremonies and state dinners. … She was planning to leave the service in 2027 and had already applied for medical school at Mount Sinai. Helicopter flying was not something she intended to pursue.

Though talented as a manager, she wasn’t much of a pilot. … One instructor described her skills as “well below average,” noting that she had “lots of difficulties in the aircraft.” Three years before, she’d failed the night-vision evaluation she was taking tonight. … It’s not uncommon for pilots to struggle during the early phase of their career. But Lobach’s development had been particularly slow. In her five years in the service, she had accumulated just 454 hours of flight time, and she wasn’t clocking more very quickly.

Captain Lobach had the same number of hours as a Big Tech engineer who flies recreationally for about three years and, based on the above, far less interest in becoming proficient. The small number of hours seems to be common within the Army:

Similar problems exist throughout Army aviation; the service has been having a hard time retaining its most experienced pilots and providing adequate flight time for those currently coming up through the ranks. Since 2011, the average number of hours flown per year by crewed Army aircraft has fallen from 302 to 198.

Here’s a confusing part. Maybe the issue was with the tail rotor rather than “a tail fin”?

As they passed over the Civil War battlefield of Thoroughfare Gap, an alarm called a master caution went off, indicating that a control system for a tail fin was malfunctioning. If the situation worsened and the surface became stuck, the helicopter could crash.

(This was unrelated to the crash as it happened an hour earlier and the system was “reset”.)

The conclusion of the article is bizarre. After writing about a person who wasn’t interested in aviation, the author concludes with a quote from the pilot-brother of one of the regional airline pilots who was killed by the Army crew’s incompetence:

He thinks that Lobach could have become a good pilot if they gave her another thousand hours of flying time. Instead, the Army withheld from her the training and flight time that she needed to fly safely and then required her to go fly anyway on a mission that was as ill-conceived as it was poorly executed.

The article is heartbreaking because there are thousands of superb civilian helicopter pilots who would have sacrificed almost anything to take Captain Lobach’s place behind the controls of a Blackhawk even without receiving her Army pay and benefits ($150,000/year if we include housing allowance and the actuarial value of the pension?). It’s understandable that the military is a bureaucracy, but after all of the selection hurdles how does it end up with pilots who don’t love to fly and live to fly?

If someone more competent was flying, they would still be routinely using the widow maker corridor today. Eventually, there was going to be a collision. It might have been a bigger passenger plane. Sounds like the military is in disrepair while all the money is going to Mcclean mansions.

Sad. Her skills are badly needed now. Tragedy just by the time the Air Force needed more pilots to fly ex-ISIS soldiers detained by Syrian Kurds to their civilian destinations in accepting western countries.

RIP all the victims of using Big Army by social climbers.

Why is the military allowing any flight path which crosses over an active airport runway approach? Does anyone think this wise or prudent?

Please don’t tell me this is done elsewhere. It shouldn’t be allowed. Period.

> because there are thousands of superb civilian helicopter pilots who would have sacrificed almost anything to take Captain Lobach’s place behind the controls of a Blackhawk

Would they be willing to fly into say, Mogadishu, once the Army provided them with hours?

I’ve ridden the Capitol subway:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Capitol_subway_system

maybe they should build that out farther, and keep VIPs subsurface where they belong. (Even on that there was a crash in 2007.) Get E. Musk to dig it for them. If Washington lacks one thing it is expensive pork-barrel projects to make the life of officials more cushy.

Perhaps I should re-read Heller’s Catch-22, as an armchair analyst, before attempting to sort this out. I find it taking more tolerance for logical contradiction and absurdity than *my* previous training and experience has given me. “Situation normal” (all F-ed up) in post-normal times.

Thoroughfare Gap and the battlefield are where I-66 passes through the first range of mountains. If you’ve driven it you will remember the burned-out,4-5 story stone mill on the north side. The gap has significantly (500-1,000 foot) higher hills on each side and is heavily wooded, not much altitude if they were flying through the gap or any space to put down if there was a control problem. Since the crash took place at about 275 feet and she was supposed to be below 200, the more experienced pilot was probably not trying to overload her as she came past Haines Point and made the last turn on the river. Sounds like a good girl and a marginal pilot flying a bit overwhelmed. I can think of two other cases of fine young women given a bit to much “benefit of the doubt” when it came to flying. Incredibly sad for all concerned including her family.