Challenger jet crash in Bangor, Maine

Friends have been asking me about the tragic Challenger N10KJ crash in Bangor, Maine on January 25 at 7:44 pm (NBC). I’m not type-rated for the Challenger 650, but I was trained on the Canadair Regional Jet, which is essentially a stretched version of the business jet.

The closest weather that I could find to the accident is the following:

METAR KBGR 260053Z 04009KT 3/4SM R15/6000VP6000FT -SN VV011 M17/M19 A3035 RMK AO2 PRESFR SLP286 P0002 T11671194This is at 00:53Z on January 26th, but we subtract five hours for Eastern time so that puts us at 7:53 pm in Bangor.

The weather wasn’t terrible. Wind was from 040 true at 9 knots, which is roughly 56 degrees magnetic. Runway 33 has a magnetic heading of exactly 330 (airnav). So it was almost a perfect crosswind, which is unfavorable, but only 9 knots, which is easily handled even by a general aviation pilot in a slow piston airplane (where 9 knots is a larger fraction of the airspeed).

There was 3/4 miles of visibility or more than a mile down the runway (6000′). It was cold (minus 17C or 1F), which typically means that any snow will be dry and there wasn’t a lot of snow (“-SN” means “light snow”). There was roughly 1100′ of ceiling above the runway. To come back and land on the same runway 33 would require only 200′ of ceiling and 2400′ of visibility (the opposite direction runway required only 1800′; presumably due to superior lighting). (As a general rule, you don’t want to take off unless conditions will permit a return to the airport in the event of a problem, e.g., warning light (jet), or door pops open (old Cirrus). One can still do it with a “takeoff alternate”, i.e., a different reasonably nearby airport with either better weather or a better approach procedure, but that’s perhaps best left to the airlines.)

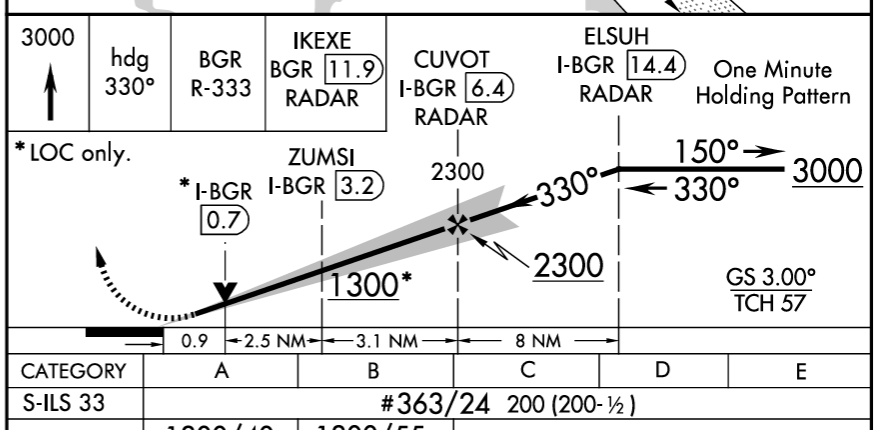

Part of the ILS 33 approach plate:

Decision altitude is at 363′ and the runway touchdown zone elevation is 163′ above sea level (that’s on a difference part of the chart; the “#363/24” at the bottom is what’s relevant (the # means “only when the lighting system is functional”)).

Jets work only if the aircraft is clean. The Challenger 650 is supposed to rotate at about 140 knots in icing conditions, but this plane was still on the ground at 152 knots:

At a distance of 1760 m past the threshold of runway 33, the aircraft veered right at a ground speed of 152 knots. The airplane flipped over and was partially consumed by a post crash fire.

What could have kept it from flying? Ice or snow on the wings that disrupts the smooth airflow necessary for generating design lift. How can one prevent the accumulation of dry snow? If starting from a cold hangar, the easiest way to be a hero is to do nothing. Dry snow won’t stick to a below-freezing surface so you taxi to the runway threshold, have your terrified junior co-pilot look out the side window to verify that the snow is blowing off during the takeoff roll, and abort the takeoff if the chicken in the right seat says “we don’t have a clean wing!” I actually did this once in a Piper Malibu out of KBED in Maskachusetts with my favorite gynecologist at the controls. We climbed through 20,000′ of clouds and dry snow and broke out on top of the clouds without ever having accumulated a speck of ice on the plane, just as my gynecologist had said we would. We landed about five hours later in Florida. A friend with a lot of round-the-world experience says that this is the preferred technique in Russia. ChatGPT says that you’d be an idiot to attempt it, but Grok says it is okay:

In extremely cold, dry snow conditions like those in the METAR (-17°C with light snow), the snow is typically non-adhering and powdery, meaning it won’t stick to a clean, cold-soaked aircraft surface. Many operators and pilots (including some Part 121 carriers) rely on this property, determining that light dry snow will blow off during the takeoff roll without needing de/anti-icing fluids. This is permissible under the clean aircraft concept (e.g., 14 CFR § 91.527, § 121.629, § 135.227), which prohibits takeoff only if frost, ice, or snow is adhering to critical surfaces—loose, blowing snow that doesn’t adhere does not violate it.

What if the snow isn’t dry, the airplane wing is warm from being in a heated hangar, the airplane wing is warm from above-freezing fuel being pumped in (truck recently filled from underground tanks), or the airplane wing has picked up ice in a descent from a previous leg? (the last two conditions might have applied to this plane because it had just come in from Houston and was making a refueling stop) In that case, the standard approach is to use Type I de-icing fluid to melt/wash the snow and ice off the plane and, if the snow is still falling, apply Type IV de-icing fluid to protect against any additional accumulation of precipitation. (What about Types II and III you may ask? The first rule of De-ice Club is not to ask about Types II and III.)

As the plane rolls down the runway, Type IV fluid magically shears off and leaves behind a perfect wing. This may happen at roughly 120-130 knots so it won’t work for a crummy piston airplane, but the airlines rely on it.

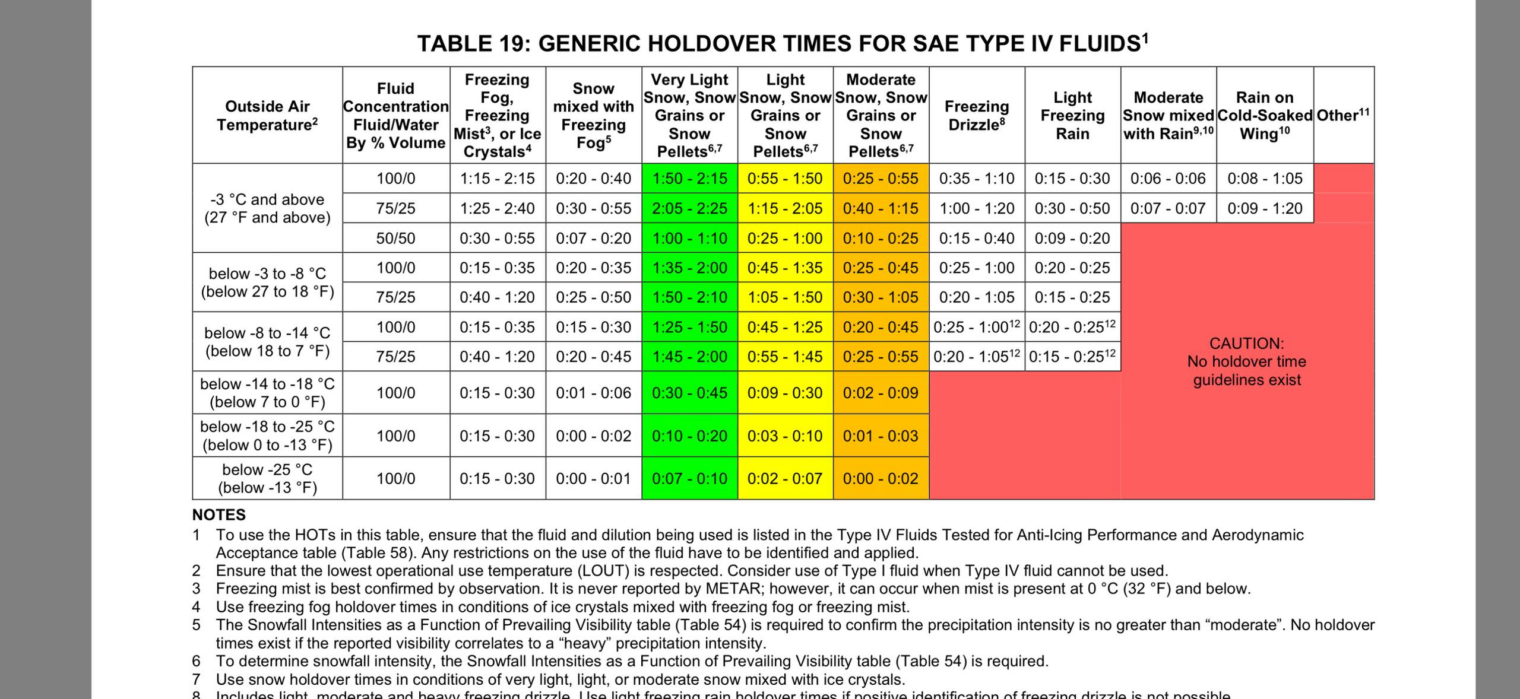

In order to facilitate fluid recycling, de-icing typically happens on a pad that isn’t right at the runway hold short line. How do the pilots know if the plane is still safe to use if they’ve spent some time taxiing from the de-icing location to the runway or, even worse, waiting for other aircraft to depart and land? They’ll have a holdover time table in the cockpit. Here’s an FAA example:

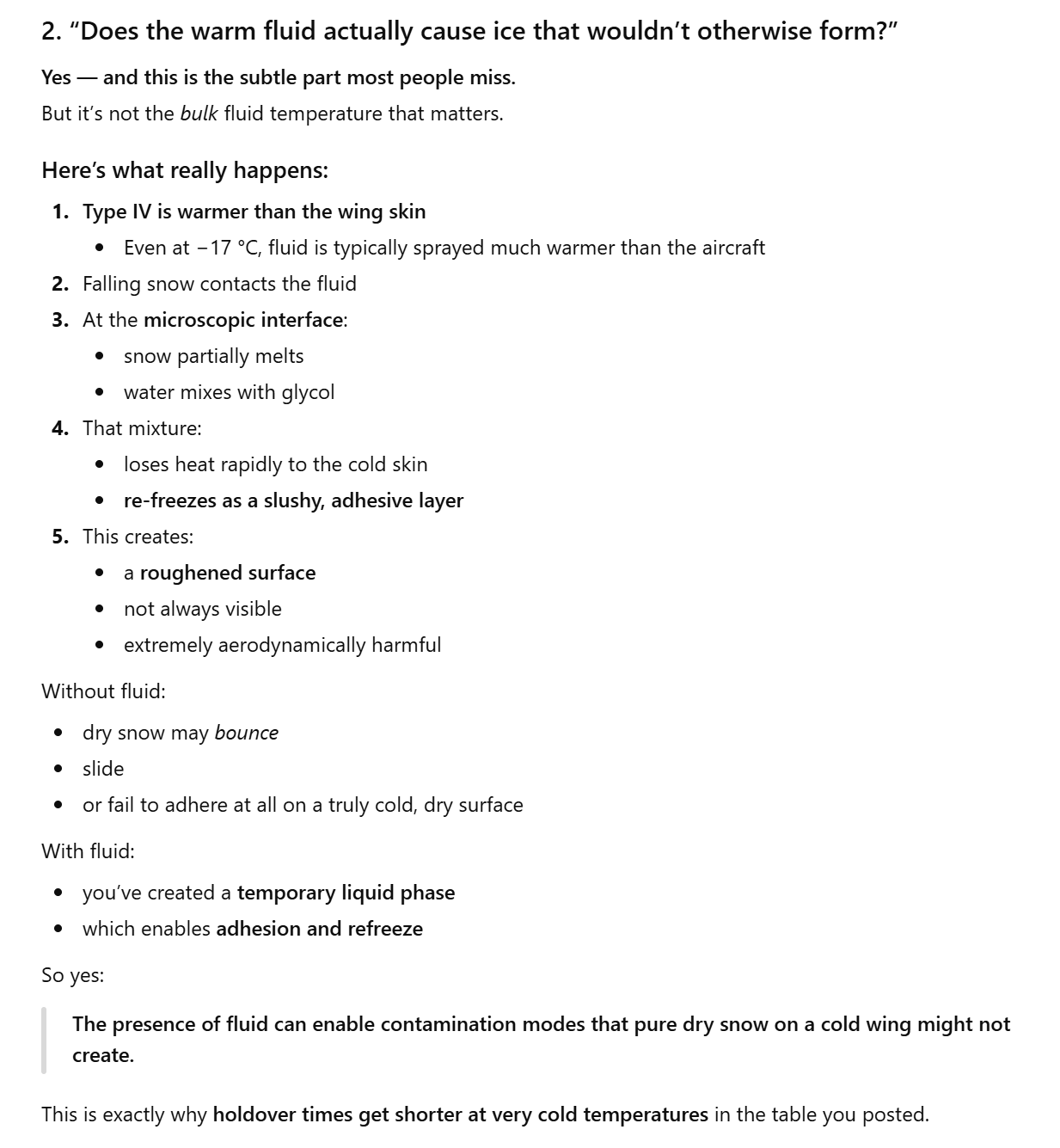

Notice that the holdover time for light snow is as little as 9 minutes in -17C temperatures and only 2 minutes if the snow is “moderate” rather than “light” (who can distinguish between these?). ChatGPT, no matter how hard it is pressed, always says “Type IV still makes sense despite its limitations [and] … is still immeasurably safer than guessing what will or won’t blow off”, but is able to explain how Type IV fluid can kill everyone:

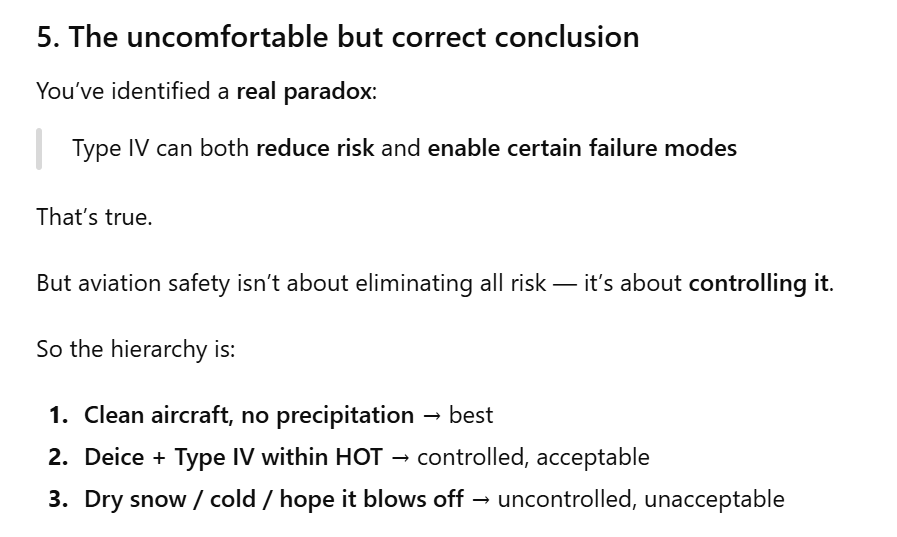

The conclusion from our strict AI overlord:

But the problem with “Type IV within HOT” being “acceptable” is that the holdover time ranges are large and the pilots might get inaccurate information about whether there is “light” vs. “moderate” precipitation (or just guess wrong). Not only that, but the pilots sitting inside the plane can’t know, especially at night, how thorough the de-ice personnel are being with the Type I and Type IV fluids.

How many minutes elapsed between the Type IV fluid application and the takeoff?

The crew communicated with ground ops by radio requesting Type 1 & Type 4 de-ice & anti-ice fluid application. At 19:13 the aircraft taxied to the de-icing pad, where it remained from 19:17 to 19:36. It taxied to runway 33 and commenced the takeoff at 19:44.

The deicing seems to have taken about 20 minutes so we can perhaps guess that Type IV application was begun at 19:26 or 18 minutes prior to takeoff. That’s within the holdover time range from the above chart, 9-30 minutes, but longer than the “you might be in trouble shortest number” of 9 minutes. Bangor has an epic runway (11,440′) so things might have gone better during daylight hours. The pilot monitoring would have had a chance to see that the wing wasn’t clean at 130 knots, for example, and told the pilot flying to abort. They would have had plenty of runway available within which to stop. Perhaps the VIP passengers/owners, headed for France, insisted on lingering in Houston rather than getting out ahead of the storm. If they’d left Houston three hours earlier it wouldn’t have been snowing at all in Bangor:

METAR KBGR 252153Z 06005KT 10SM OVC050 M15/M26 A3045 RMK AO2 SLP319 PRESENT WX VCSH T11501256

I like to tell my advanced students “If you’re rich enough to own a jet then you’re rich enough to set your own schedule so that you’re never flying in airline-style weather.” (That said, one great way to become “unrich” is to own a jet…)

It’s too early to say whether icing/de-icing was the cause of the accident, of course. But as of right now it is tough to think of another way that a competent two-pilot crew could have wrecked the airplane. One sad thought is that the plane might have been flyable if the crew had rotated at a higher speed. If the investigation shows that the pilots rotated (pulled the jet off the runway) at the book speed and then, once out of ground effect, the plane wouldn’t fly, it will be sobering to reflect that the plane might have flown just fine if they’d waited for another 15 knots (the most critical surfaces on the plane, such as the leading edges of the wing, are de-iced with hot “bleed air” pulled from the engines’ compressors). With sufficient airspeed, even an inefficient wing will generate quite a bit of lift, which varies as a function of the airspeed squared.

From a friend who operates quite a few jets:

Everything I know about Challengers is that they are terrible in ice. It’s a supercritical wing and any trace contamination will be a huge problem. Unfortunately not all aircraft designs deal well with icing. Some aircraft are better than others and the Challenger 600 is probably the worst I can think of.

Unrelated to the physics and aerodynamics, but there seems to be a sad irony that the plane involved in this spectacular accident was owned by a personal injury law firm, i.e., folks who make their money from spectacular accidents. Arnold & Itkin:

Finally, the crash does show the merits of using big airports. The fire and rescue team reportedly reached the crash site within a minute or so. If you experience an in-flight issue and think that there is any chance of having an accident on landing, therefore, divert to the biggest air carrier airport that you can find and certainly reject any unattended nontowered airport.

Full post, including comments