Bad year for air shows and the U.S. military

Readers: Who has some good ideas for air shows this year? My personal favorite, the Rhode Island Air Show, has been canceled (NBC) :

“Hundreds of key National Guard members will be called to federal duty overseas in support of the RING’s primary mission of national defense,” a news release said.

“With this anticipated federal mobilization commitment in 2019, we have been presented with a difficult decision regarding our ability to safely and effectively conduct this public event. The volume, timing, and the particular trained skill sets of the more than 500 Soldiers and Airmen who will be away during the traditional timeframe of the Open House Air Show presents a unique challenge,” Maj. Gen. Christopher Callahan said in a statement. “Ultimately, we could neither compromise the training and support of those being deployed, nor the planning and conducting of our Open House Air Show. As such, we regrettably must forego the event in 2019.”

So New Englanders are out of luck, particular considering what a total Charlie-Foxtrot the Westover show is (see https://philip.greenspun.com/blog/2018/07/13/great-new-england-air-show-this-weekend-at-westover/ ).

Excited about a female pilot flying a fighter plane (like Hannah Reitsch?) in a tight pattern around the runway? You’re out of luck there too: “Zoe Kotnik: First female F-16 demo commander out after two weeks” (BBC)

Here are some ideas:

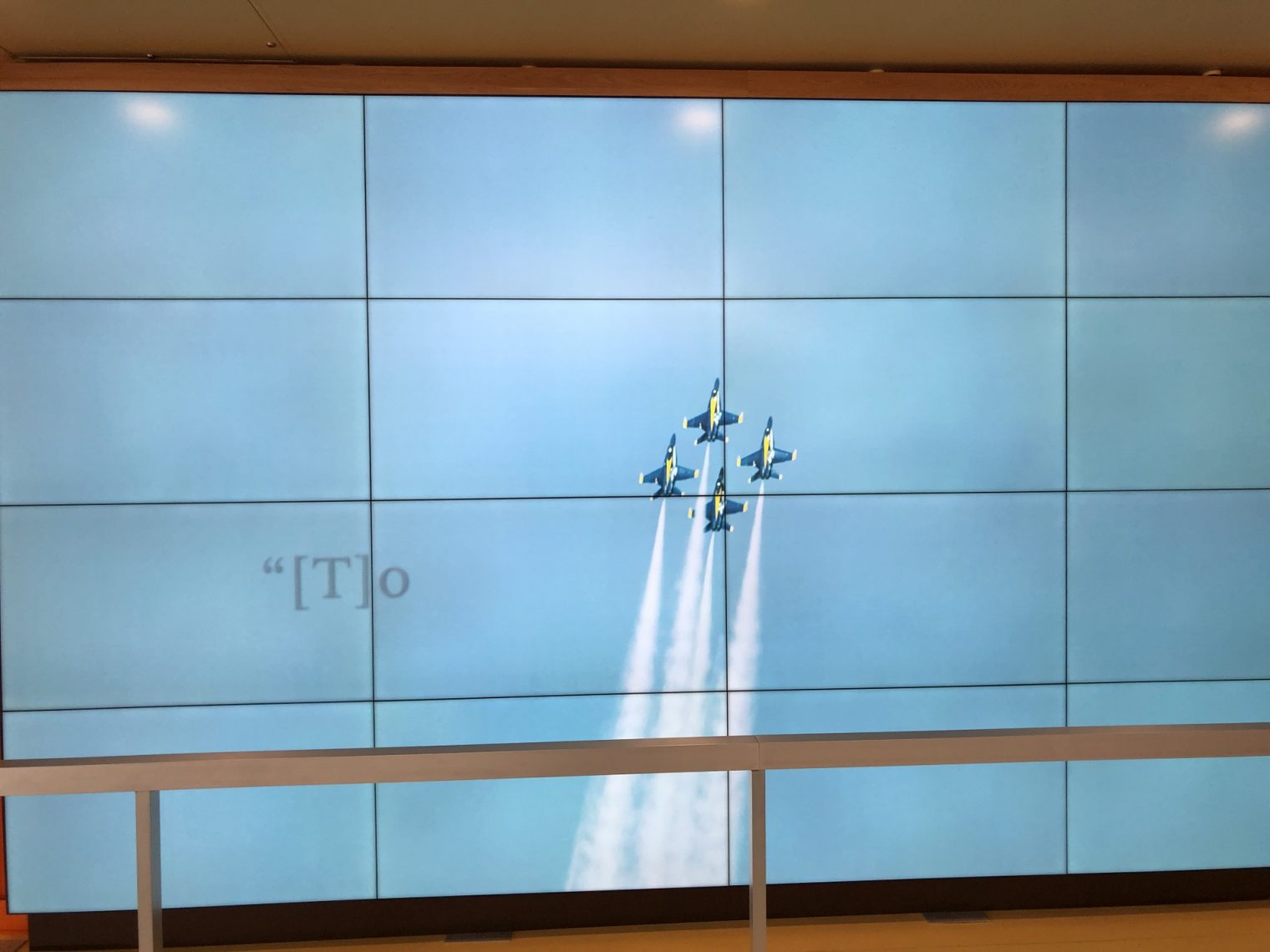

- April 6-7: Blue Angels in Lakeland, FL at Sun & Fun (Oshkosh Lite)

- May 4-5: Blue Angels at Ft. Lauderdale Air Show (on the beach, so all roads lead to the show!)

- May 25-26: Blue Angels at Miami Beach Air and Sea Show (same deal; how much worse can the traffic be than usual for Miami?)

- June 15-16: Blue Angels at Ocean City (Maryland) Air Show

- June 29-30: Thunderbirds in Traverse City, Michigan

- July 22-28: Airventure at Oshkosh; air show every afternoon and two evenings!

- August 21: Thunderbirds at the Atlantic City (NJ) Air Show

- August 24-25: Blue Angels at KSWF (New York; good for New Englanders); Thunderbirds in Rochester, NY (proceed to Niagara Falls after?)

- August 31-September 1: Blue Angels in Nova Scotia (how bad can the crowds be?)

- September 14-15: Thunderbirds at the Reno Air Races (could an F-16 beat a Glasair?)

- October 5-6: Thunderbirds in San Juan, Puerto Rico (if you’re escaping AOC’s income tax and Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax (payable in wampum?) to enjoy a tax-free lifestyle)

- October 19-20: Blue Angels in Jacksonville Beach; Red Bull Air Race in Indianapolis (only US location)