I promised more about House of Huawei: The Secret History of China’s Most Powerful Company (see Unprovoked genocide against the Uyghurs) and here it is…

The book covers the modern history of China as well as the history of Huawei. The book should be inspiring to us older folks because the founder of Huawei was born in 1944 and, at age 81, is still involved in corporate management:

In Guizhou, Ren Moxun met a seventeen-year-old named Cheng Yuanzhao. With big brown eyes,[15] round cheeks, and a broad smile, she was also bright and good with numbers. They married, and Cheng Yuanzhao soon became pregnant. Their son was born in October 1944, and they named him Ren Zhengfei. It was an ambiguous name. Zheng meant “correct,” and fei meant “not.” “Right or wrong” would be a fair translation.

We are reminded that China is a multi-ethnic empire:

Mao’s officials believed they were extending a civilizing influence to the nation’s frontiers—Guizhou in the south, Inner Mongolia in the north, Tibet and Xinjiang in the west. The residents didn’t necessarily see it that way. They had lived for centuries with their own languages and customs, and they were now being compelled to assimilate. There were those who did not like Ren Moxun and his school either. After someone threatened to kill him with a hand grenade—the precise reasons are unclear—the school was issued four rifles to protect the staff and students. One of Ren Moxun’s objectives was to inculcate his students with the right beliefs. “Principal Ren, your guiding ideology must be clear,” a visiting official instructed him. “You must make clear who the enemies are, who we are, who are our friends.” Ren Moxun organized rallies for the students to denounce their enemies. The enemies at home were the oppressive landlords. The enemies abroad were the Americans, who were waging war against North Korea, one of China’s allies. Ren Moxun reported that the “scoundrels” hidden among the teachers were successfully caught through these criticism sessions, which were often intense, with students bursting into tears. In the anti-America sessions, students offered up secondhand accounts of atrocities committed by US troops in the area, presumably when they had passed through during World War II. One student said a US soldier had shot a farmer for sport near the Yellow Fruit Waterfall. Another said a classmate’s sister had been dragged into a jeep and raped. It was hard to say what, exactly, had happened years ago with US soldiers, but the resentment against America was certainly real.

and that the Cultural Revolution wasn’t a great time to be an educator or a student who wanted to learn

Ren Moxun was hauled onto a platform in the school cafeteria, his hands tied, his face smeared with black ink, the tall hat of shame denoting a counterrevolutionary placed on his head. “Studying is useless!” people shouted. “The more knowledge you possess, the more reactionary you are!”

One of Ren Moxun’s students demanded the principal admit that he’d instilled feudalist thinking in the students, such as by quoting Confucius. According to a recollective essay by Feng Jugao, a different student, when Ren Moxun tried to deny the accusation, the accuser rushed forward with a wooden stick and beat him until the stick broke.[53] “I can’t say if the wooden stick was weak, or if Principal Ren’s backbone was strong,” Feng wrote. “But the wooden stick broke in two across Principal Ren’s back.” Feng recalled his mother being aghast, saying that the students who beat the principal would get their karmic punishment.

Universities nationwide were banned from matriculating any new students between 1966 and 1976. Ren Zhengfei’s younger siblings were shut out, but through the random luck of his birth year, he’d been able to eke out a college education. In 1968, Ren graduated with a major in heating, gas supply, and ventilation engineering.

At age 42, Ren started Huawei:

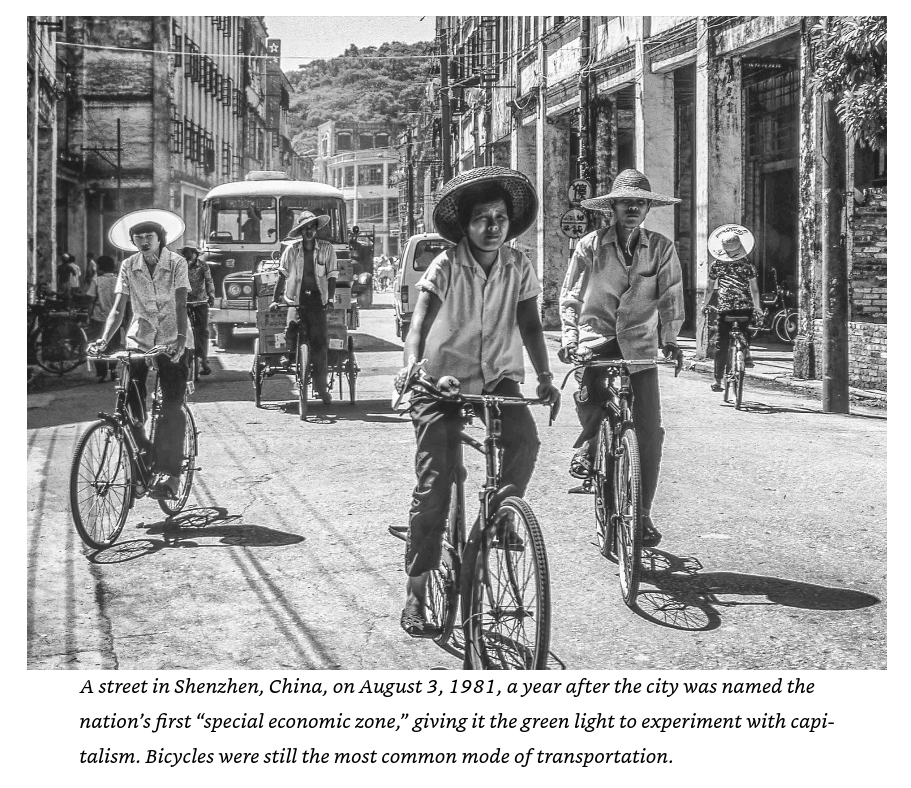

Shenzhen legalized the establishment of “minjian” (unofficial or, more literally, “among the people”) private technology companies in February 1987 under a pilot program. Applicants poured in from across the country—professors and engineers from Beijing to Kunming. The idea of running your own company in the SEZ was exciting—and risky. Seventy-five percent of the first batch of entrepreneurs asked their state employers for temporary unpaid leave, with the option of reprising their old jobs if their startups didn’t work out. Ren founded Huawei as a minjian company on September 15, 1987, with twenty-one thousand yuan pooled between himself and five investors.

Wuhan was the source for more than SARS-CoV-2 and coronapanic:

Ren arrived in the inland city of Wuhan in the spring of 1988 in search of engineers. Dubbed “the Chicago of China,” Wuhan was a bustling industrial city on the Yangtze River. The Huazhong Institute of Technology had been founded here in the 1950s, and three decades later, conditions at the university were still spare: Students bunked six to a room in the dorms and took cold-water showers.[38] There was no air-conditioning or heat. But there was a professor who was knowledgeable about telephone switching, and Ren hoped he could help Huawei build a switch.

The book covers the 1989 protests and power struggles, then returns to the early days of Huawei:

Ren’s team had been making simple analog switches that could handle forty, eighty, or, at most, a couple hundred phone calls at once. Their early attempt at a more complex one-thousand-line switch was a failure, suffering from serious cross talk, dropped calls, and a tendency to catch fire from lightning strikes. Now, in 1993, they were trying to build a digital switch that could handle ten thousand telephone calls at once. This would catapult them into the big leagues. They would no longer be selling to hotels and small offices; they would be selling directly to the telephone switching centers for entire cities.

Ren had rented the third floor of an industrial building on Shenzhen’s outskirts for his fledgling R&D team. There was no air-conditioning, only electric fans, and they took cold showers to try to keep cool. They rigged up nets to try to escape the ferocious mosquitoes. A dozen cots lined the wall. The engineers worked day and night, flopping down on mattresses to sleep for a few hours when they reached exhaustion, which led to the saying that Huawei had a “mattress culture.”[9] One engineer worked so hard that his cornea detached, requiring emergency surgery.

It wasn’t as simple as going to the state’s web site and forming a corporation or LLC:

By 1991, Huawei had ten million yuan in fixed assets and was churning out eighty million yuan worth of switches a year. It had 105 employees, the majority of whom were shareholders. That year, Huawei’s shareholders did something curious: after proudly launching themselves in 1987 as one of Shenzhen’s first wave of “minjian” private tech companies, they voted unanimously to stop being one. From 1992 to 1997, Huawei would be a jitisuoyouzhi, or a “collectively owned enterprise,” something that was neither “private” nor “state-owned” in the modern senses of the words. Indeed, such companies were most similar in spirit to the Mao-era communes: Beijing defined them as “socialist economic organizations whose property is collectively owned by the working people, who practice joint labor, and whose distribution method is based on distribution according to labor.” While collectively owned businesses had been used in the countryside to mixed success, China’s national government had, in 1991, just formalized guidelines for urban collective companies. Putting on the “red hat” of a collective was popular among startups then as a way to obtain political protection. The Stone Group—hailed as “China’s IBM” in the 1980s—had been a trailblazer in this regard, successfully switching to a “collectively owned enterprise” in 1986. The 1991 national guidelines stipulated that collectively owned enterprises could enjoy preferential treatment in national policies and apply for loans from specialized banks. The guidelines also ordered government authorities nationwide to incorporate the companies into their economic plans in order to ensure the success of the urban collective economy. It remains unclear why Ren and his team decided to switch to a jitisuoyouzhi, though it’s likely that the broader financing opportunities were attractive.

Like Jeff Bezos, who married a secretary at D.E. Shaw while he was a VP (Wokipedia says that MacKenzie Scott had “an administrative role” at D.E. Shaw, implying that she might have been a top manager; the New York Times says that she held the job of “administrative assistant” (i.e., secretary)), Ren might have married his secretary:

While the precise timeline is unclear, Ren Zhengfei had remarried at some point and was building a new family in Shenzhen. This second marriage may have taken place around 1994, according to a speech Ren gave in January 2009, in which he praised his second wife, Yao Ling, for “fifteen years of silent devotion to the family.” Yao Ling was a petite and graceful young woman, much younger than Ren, with almond-shaped eyes and a winsome smile. Some news reports referred to her as Ren’s former secretary, though this has not been confirmed by the company. Ren had called Meng Jun “very tough”; he called Yao Ling “gentle and capable.”

The company prospers partly because the Chinese government imposed a “Buy Chinese” mandate similar to the U.S.’s “Buy American” mandates:

Since Ren’s meeting with Jiang in 1994, much more government support had been pledged. At the end of 1994, Zhang told Ren that in the next five-year economic plan, half of telecom operators’ switch purchases would be reserved for purely domestic companies like Huawei. “The way I look at it,” Zhang said, “it’s not that important what type of ownership structure a company has. The important thing is if it’s Chinese. So we at the Electronics Ministry want to support a business like yours.” China would have 84 million telephone lines’ worth of switches in operation by 1995, and officials planned to more than double that to 174 million lines’ worth by 2000.

I’ll close here and pick up in another post. Meanwhile, if you’re interested, read House of Huawei: The Secret History of China’s Most Powerful Company.

Full post, including comments