What if Thomas Edison were alive today?

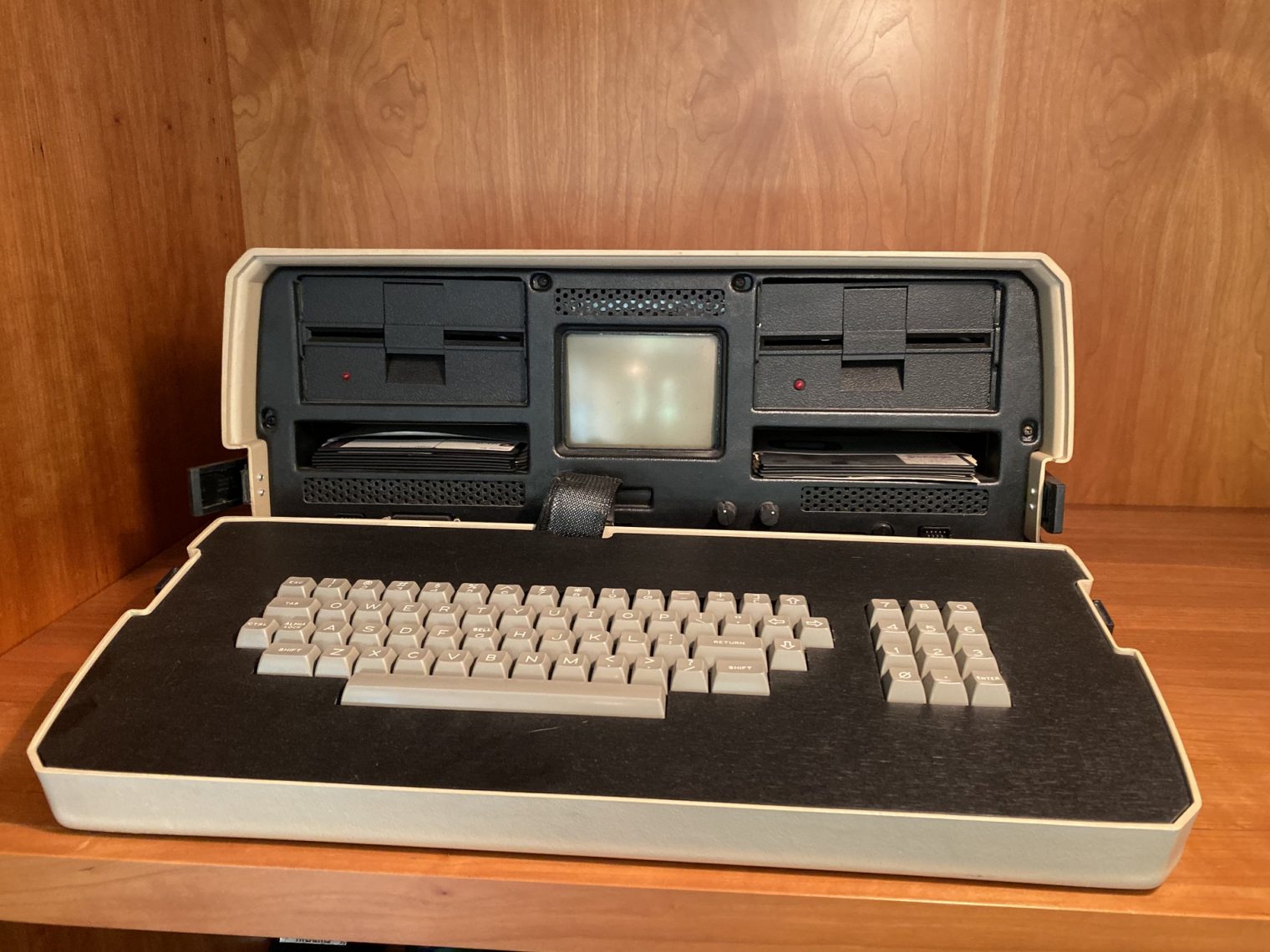

Edison by Edmund Morris, gives us some hints as to how Thomas Edison might have dealt with our society’s challenges today. (Below, Edison’s workshop, transported to Michigan by Henry Ford and now part of Greenfield Village.)

Although he was an early enthusiast for aviation, trying to build a helicopter in the 1880s, Edison (1847-1931) actually lived (and continued to work hard and effectively) through the period of the most rapid advances in aviation. He seems not to have contributed anything significant to the development of flying machines.

One thing that I learned from the book is that Edison loved huge projects and was not afraid of doing things at scale. He put about $2 million and years of work into trying to mine iron ore in New Jersey and then mill it profitably. From the early 1890s:

A party of inspectors sent by Engineering and Mining Journal toured the plant early in the fall. Although some sections were idled for refurbishment and Edison was coy about showing any of his new machines, they could see that he already excelled at quarrying and magnetic separation, if not yet in the difficult processes of crushing and refinement. They were particularly impressed with his cableway system, every suspended “skip” delivering four tons of rock to the crushers at only twelve cents a load. But they predicted that in view of the low iron content of local ore, Edison would still have to spend a fortune and deploy “the utmost resources of engineering skill” to compete with Mesabi ore at 64 percent iron. “With his surpassing genius [and] capacity for taking infinite pains, it cannot be doubted that he will ultimately achieve success.”

In July Edison learned that his mining venture had so far cost him $850,000, including some $100,000 that could not be accounted for. A profit-killing amount of money was being lavished on labor that simply loaded and unloaded rock at either end of the conveyors. The jaw crushers took too long to do their work and often broke down, necessitating expensive repairs. The magnetic separators, plagued by screening problems, were concentrating only 47 percent iron—far less than the 66 or 70 percent he needed to match the richness of Great Lakes ore. He was still digesting this information when a stockhouse under construction at Ogden collapsed, killing five men and injuring twelve. Lawsuits alleging negligence were filed by bereaved families.106 A newspaper clipping he carried in his wallet read, “Thomas Edison is a happy and healthy man. He does not worry.” As usual he countered the pull of bad news by pushing forward harder. Rather than continue to “improve” Ogden with ad hoc adjustments, he increased the capital of its parent company to $1.25 million, then shut the plant for a tear-down rebuild that would expand it enormously and make it a showpiece of automated design. No sooner had a new separator house gone up than he decided it needed some screening towers, and should be constructed all over again.

Given what we now know about the ore near Lake Superior (ore in the water of Tahquamenon Falls, below, from Travels with Samantha), the idea seems laughable today and, indeed, it was a complete failure. Nonetheless, it was amazing how many problems Edison was able to solve.

My theory about what he would be working on today, therefore, is geoengineering. He would take complaints about a warming planet as inspiration to work in the lab and then build infrastructure on the scale of the largest mines and power plants.

How about coronaplague? Edison did like to jump into solving problems that society perceived as urgent. But what kind of machine would be useful for fighting the plague? Big shade structures to move activities outdoors? Edison did put a lot of effort into “tornado-proof concrete houses”:

Last May’s catastrophic earthquake in San Francisco revived an idea he had had when the cement mill was first ready to roll. He saw low-cost, molded concrete houses replacing the fragile wooden boxes in which most Americans lived—houses that contractors would mix from cement (with a colloidal additive for grit suspension) and spill on the spot into prefabricated forms. A three-story house could be poured in six hours and set in less than a week.

He had to admit that the individual kits, consisting of nickel-plated cast iron parts, would be expensive, at around $25,000 apiece. But they would pay for themselves in frequency of use and universality of detail, molding mantelpieces, banisters, dormer windows, conduits for wiring, “and even bathtubs.” Having made the investment, a contractor could pour a new house every four days. Each could be sold for $500 or $600, enabling millions of low-income Americans to become homeowners for the first time, with no need to worry about earthquakes, hurricanes, or fire. “I will see this innovation a commonplace fact,” Edison promised, “even though I am in my sixtieth year.”

What about a wearable device that would deflect the evil coronavirus away from a person’s mouth and nose, but without obstructing breathing the way that a mask does?

Where would Edison have stood on this year’s Presidential campaign? “Edison had always been a loyal Republican,” writes Morris, but quotes Edison explaining why he voted for Teddy Roosevelt whose statue was just toppled in Manhattan: “I’m a Progressive, because I’m young at sixty-five,” he said. “And this is a young man’s movement. There are a lot of people who die in the head before they are fifty. They’re the ones who get shocked if you propose anything that wasn’t going when they were boys.” Morris says that “Edison had come to despise government bureaucrats, seeing them as a blight on democracy,” but perhaps Edison’s Progressive streak would have led him to support Bernie nonetheless!

On the third hand, Edison would probably not have been able to hold a job in the present-day U.S.:

Relations between him and [son] Charles warmed to the extent they could resume their old exchange of “negro jokes.”

Wikipedia points out that Edison married a subordinate whom we would today call “underage”:

On December 25, 1871, at the age of 24, Edison married 16-year-old Mary Stilwell (1855–1884), whom he had met two months earlier; she was an employee at one of his shops.

Mary likely died, only 28 years old, in the modern American manner. The author quotes from a contemporary source:

At the request of Mr. Edison she took a trip to Florida last winter. Instead of obtaining relief she fell victim to gastritis, due to the peculiar atmosphere or perhaps the long acquaintance with morphine. She returned to Menlo Park in a more troubled condition. Her pain intensified, and at times she was almost frantic. Morphia was the only remedy, and naturally she tried to increase the quantity prescribed by the doctors. From the careless word dropped by [a] friend of the family it was more than intimated that an overdose of morphine swallowed in a moment of frenzy caused by pain greater than she could bear brought on her untimely death. The doctor in attendance said she died of congestion of the brain. When a reporter put the question to him he positively asserted that it was the immediate cause, but about the more remote causes he preferred to remain silent.

(1.5 years later, Edison was 39 and married Mina, age 20.)

What about shutting down schools, society, and the economy for three months so as to end up with the same death rate from Covid-19 as Sweden?

as Edison lay dying [in 1931, age 84], it was suggested to President Hoover that the entire electrical system of the United States should be shut off for one minute on the night of his interment. But Hoover realized that such a gesture would immobilize the nation and quite possibly kill countless people.

Readers: Fun speculation for today… suppose that Thomas Edison were alive today, age 40, and had $1 billion available to invest. What problem would he attack?

More: Read Edison by Edmund Morris.

Full post, including comments