My friends on Facebook are delirious with joy that Washington, D.C. is being closed off to ordinary people and that more 26,000 U.S. military troops are guarding the Capitol against potential domestic enemies. I’m not sure why the 3,800 D.C. police officers, 2,300 Capitol police officers. U.S. Secret Service agents, FBI agents, U.S. Park Police, et al. cannot protect the U.S. government from its subjects. But I wonder if it could be done at a lower cost.

“Migrant Caravan, Now in Guatemala, Tests Regional Resolve to Control Migration” (New York Times):

As many as 7,000 migrants from Central America are hoping to reach the United States to escape poverty intensified by hurricanes and the pandemic. President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr. has pledged to ease asylum rules.

Wielding truncheons and firing tear gas, Guatemalan security forces on Sunday stepped up their efforts to stop a caravan of thousands of Central American migrants who have surged in from Honduras in recent days in hopes of reaching the United States.

Shortly after dawn on Sunday, migrants tried to force their way through the phalanx but were beaten back by security forces with truncheons, shields and clouds of tear gas, according to the local news media and a video circulated by the Guatemalan government.

“Fortunately, our security forces managed to contain this pitched battle,” said Guillermo Díaz, director general of the Guatemalan Migration Institute. “We managed to calm everything in a very complicated situation.” He added, “We are talking about national security here.”

Instead of mobilizing costly U.S. military forces, why not pay the Guatemalans to keep us safe from ourselves?

Separately, I had always wondered why we needed to spend nearly $1 trillion per year on a military that served no apparent purpose. The Soviet Union was mostly an enemy in our own minds. Canada and Mexico still haven’t invaded. Our military didn’t do anything to stop up to 29 million undocumented migrants from crossing the border and settling down in recent years. Maybe the real purpose of the U.S. military is simply domestic policing?

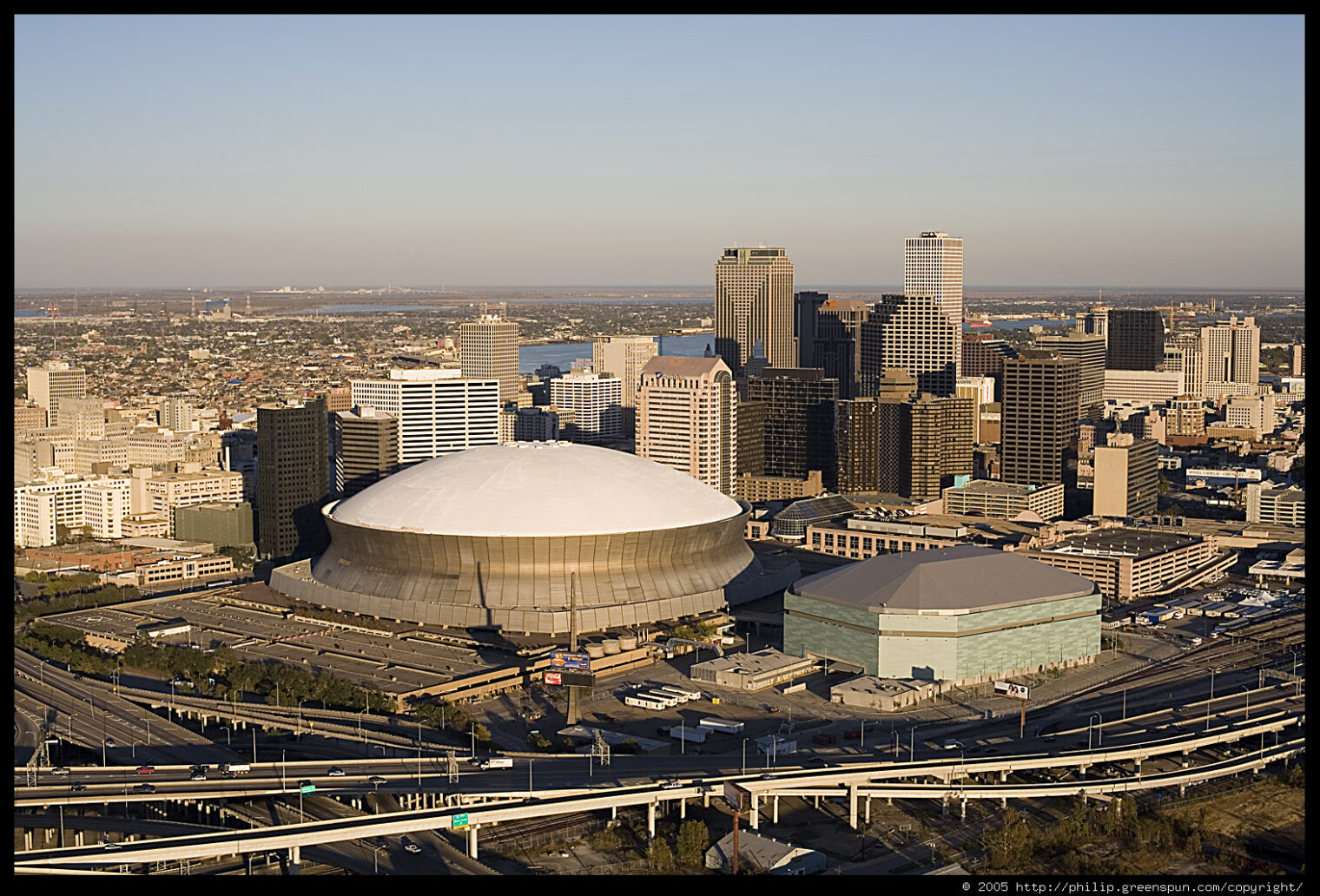

Tikal, Guatemala, from 2000 (captured with the Mamiya 7 medium format camera):

And the flower market in Chichicastenango…

Before coronapanic, friends regularly traveled to the UNESCO World Heritage site of Antigua, Guatemala for Spanish lessons and relaxation. Why not travel there to find folks with a proven track at controlling a determined crowd without lethal violence?

Update from Facebook:

Full post, including comments