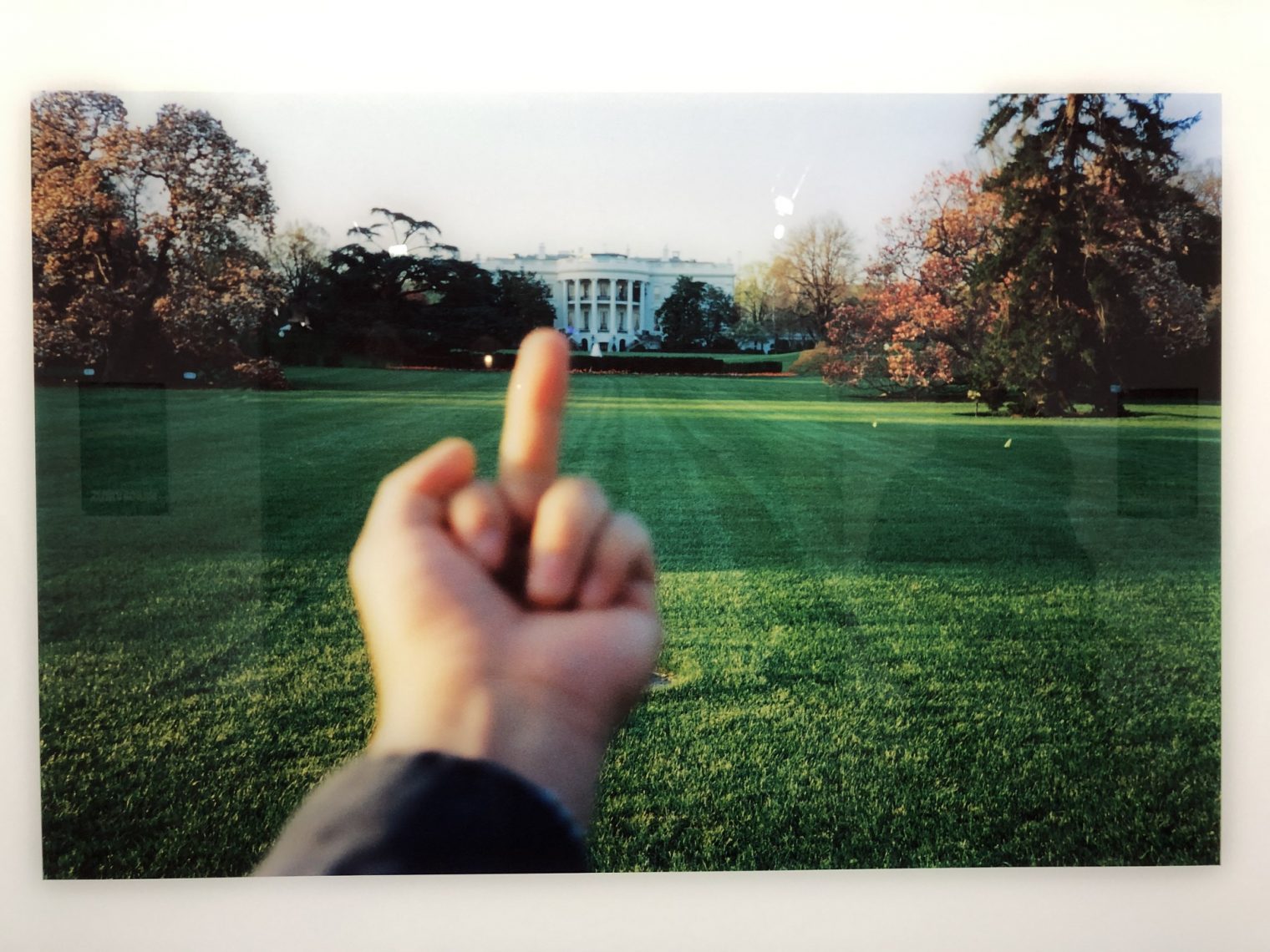

Move to the UK if you’re an entrepreneur? (10 percent capital gains tax)

Beginning of a new year and time for some tax planning. If you’re not a U.S. citizen and thus subject to worldwide taxation, maybe it is time to move to the U.K.? The all-in tax rate for “entrepreneurs” is 10 percent for capital gains (see Entrepreneurs’ Tax Relief). Compare to 37.1 percent for a California resident (20 percent federal plus 13.3 percent to uphold virtue within the state plus 3.8 percent Obamacare tax).

Full post, including comments