Brain surgeon tortured by software developers and hospital bureaucrats

Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death, and Brain Surgery (Marsh) offers readers a window into the world of neurosurgery. The author chronicles the assault on the top neurosurgeon’s privileges by mediocre software developers and hospital bureaucrats and highlights the fact that paperwork has advanced way beyond human capacity. Here is part of one vignette:

‘Informed consent’ sounds so easy in principle – the surgeon explains the balance of risks and benefits, and the calm and rational patient decides what he or she wants – just like going to the supermarket and choosing from the vast array of toothbrushes on offer. The reality is very different. Patients are both terrified and ignorant. How are they to know whether the surgeon is competent or not? They will try to overcome their fear by investing the surgeon with superhuman abilities.

I told him that there was a one or two per cent risk of his dying or having a stroke if the operation went badly. In truth, I did not know the exact figure as I have only operated on a few tumours like his – ones as large as his are very rare – but I dislike terrorizing patients when I know that they have to have an operation.

Taking the pen I offered him he signed the long and complicated form, printed on yellow paper and several pages in length, with a special section on the legal disposal of body parts. He did not read it – I have yet to find anybody who does. I told him that he would be admitted for surgery the following Monday.

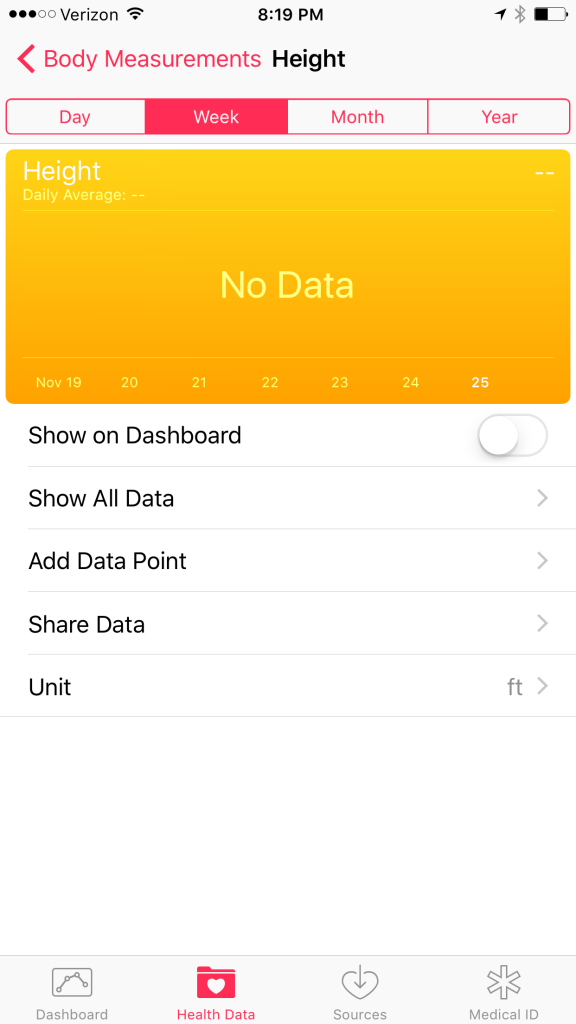

‘Sent for the patient?’ I asked as I entered the operating theatre on Monday morning. ‘No,’ said U-Nok the ODA (the member of the theatre team who assists the anaesthetist). ‘No blood.’ ‘But the patient has been in the building for two days already,’ I said. U-Nok, a delightful Korean woman, smiled apologetically but said nothing in reply. ‘The bloods had to be sent off again at six this morning,’ said the anaesthetist as she entered the room. ‘They had to be done again because yesterday’s bloods were on the old EPR system which has stopped working for some reason because of the new hospital computer system which went live today. The patient now has a different number apparently and we can’t find the results from all the blood tests sent yesterday.’

Is it any better here? A friend who is a doc at a Boston-area hospital said that they’re hoping in about two years to get back, from their $2 billion Epic system, most of the capabilities they had in their old (home-grown) electronic medical record system.

Where does the experienced brain surgeon fit into the hospital hierarchy?

‘What’s all this about cancelling the last case?’ I asked. The anaesthetist was indeed a new one – a locum recently appointed to replace my regular anaesthetist who was on maternity leave. We had done a few lists together and she had seemed competent and pleasant. ‘I’m not starting a big meningioma at 4 p.m.,’ she declared, turning towards me. ‘I’ve got no childcare this evening.’ ‘But we can’t cancel it,’ I protested. ‘She was cancelled once already!’ ‘Well I’m not doing it.’ ‘You’ll have to ask your colleagues then,’ I said. ‘I don’t think they will, it’s not an emergency,’ she replied in a slow and final tone of voice. For a few moments I was struck dumb. I thought of how until a few years ago a problem like this would never have arisen. I always try to finish the list at a reasonable time but in the past everybody accepted that sometimes the list would have to run late. In the pre-modern NHS consultants never counted their hours – you just went on working until the work was done. I felt an almost overwhelming urge to play the part of a furious, raging surgeon and wanted to roar out, as I would have done in the past: ‘Bugger childcare! You’ll never work with me again!’ But it would have been an empty threat since I have little say in who anaesthetizes my patients. Besides, surgeons can no longer get away with such behaviour. I envy the way in which the generation who trained me could relieve the intense stress of their work by losing their temper, at times quite outrageously, without fear of being had up for bullying and harassment.

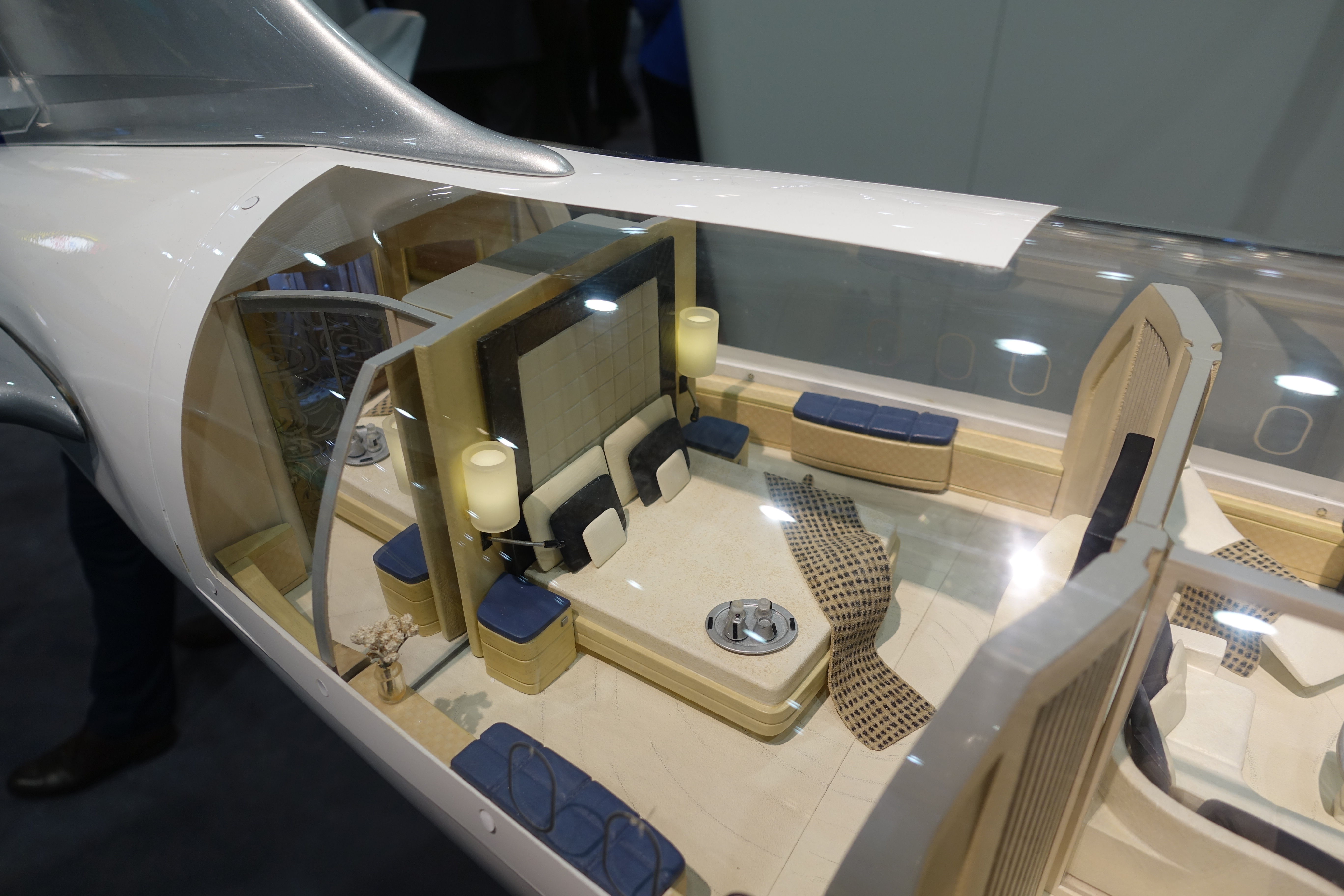

When our department was moved from the old hospital to a newly built block at the main hospital some miles away, the entire second floor of the new building was dedicated to neurosurgery. As time passed, however, the management started to reduce our facilities and one of the neurosurgical theatres became a theatre for bariatric surgery – surgery for morbidly obese people. The corridors and rooms were starting to fill with unfamiliar faces and patients the size of small whales being wheeled past on trolleys.

How does IT help?

As she talked she typed on the keyboard and the slices of a huge black-and-white brain scan started to appear, like a death sentence, out of the dark onto the white wall in front of us. ‘You won’t believe this,’ one of the other registrars broke in. ‘I was on yesterday evening and took the call. They sent the scan on a CD but because of that crap from the government about confidentiality they sent two taxis. Two taxis! One for the fucking CD and one for the little piece of paper with the fucking encryption password! For an emergency! How stupid can you get?’ We all laughed, apart from the registrar presenting the case who waited for us to calm down.

I went down to my office where I found my secretary Gail cursing her computer again while she tried to get onto one of the hospital databases.

‘This may take a while,’ I added. ‘The scans are on the computer network of your local hospital and this is then linked over the net to our system…’ As I spoke I typed on the keyboard looking for the icon for his hospital’s X-ray network. I found it and summoned up a password box. I have lost count of the number of different passwords I now need to get my work done every day. I spent five minutes failing to get into the system. I was painfully aware of the anxious man and his family watching my every move, waiting to hear if I would be reading him his death sentence or not. ‘It was so much easier in the past,’ I sighed, pointing at the redundant light-screen in front of my desk. ‘Just thirty seconds to put an X-ray film up onto the X-ray screen. I’ve tried every bloody password I know.’ I could have added that the previous week I had had to send four of the twelve patients home from the clinic without having been able to see their scans, so that the appointments had been entirely wasted and the patients made even more anxious and unhappy. ‘It’s just like this with the police force,’ the patient said. ‘Everything’s computerized and we are constantly being told what to do but nothing works as well as it used to.

‘Have you tried your password?’ ‘Yes, I bloody well have.’ ‘Well, try Mr Johnston’s. That usually works. Fuck Off 45. He hates computers.’ ‘Why forty-five?’ ‘It’s the forty-fifth month since we signed onto that hospital’s system and one has to change the password every month,’ Caroline replied.

‘When can I start?’ I asked, unhappy at being kept waiting when I had a dangerous and difficult case to do. Starting on time, with everything just right, and the surgical drapes placed in exactly the right way, the instruments tidily laid out, is an important way of calming surgical stage fright. ‘A couple of hours at least.’ I said that there was a poster downstairs saying that iCLIP, the new computer system should only keep patients waiting a few extra minutes. The anaesthetist laughed in reply. I left the room. Years ago, I would have stormed off in a rage, demanding that something be done, but my anger has come to be replaced by fatalistic despair as I have been forced to recognize my complete impotence as just another doctor faced by yet another new computer program in a huge, modern hospital.

What role does management play?

I returned to the Training and Development Centre. The second session had already started. The PowerPoint presentation now showed a slide with a long list of the Principles of Customer Service and Care. ‘Communicate effectively,’ I read. ‘Pay attention to detail. Act promptly.’ We were also advised to develop Empathy. ‘You must stay composed and calm,’ Chris the lecturer told us. ‘Think clearly and stay focused. Your emotions can affect your behaviour.’

The new chief executive for the Trust, the seventh since I had become a consultant, was especially keen on the twenty-two-page Trust Dress Code and my colleagues and I had recently been threatened with disciplinary action for wearing ties and wristwatches. There is no evidence that consultants wearing ties and wristwatches contributes to hospital infections, but the chief executive viewed the matter so seriously that he had taken to dressing as a nurse and following us on our ward rounds, refusing to talk to us and instead making copious notes. He did, however, wear his chief executive badge – I suppose just in case somebody asked him to empty a bedpan.

How does all of this affect Dr. Marsh?

Not for the first time, I thought of the trivial nature of any problems that I might have compared to my patients’ and felt ashamed and disappointed that I still worry about them nevertheless. You might expect that seeing so much pain and suffering might help you keep your own difficulties in perspective but, alas, it does not.

More: Read Do No Harm: Stories of Life, Death, and Brain Surgery.