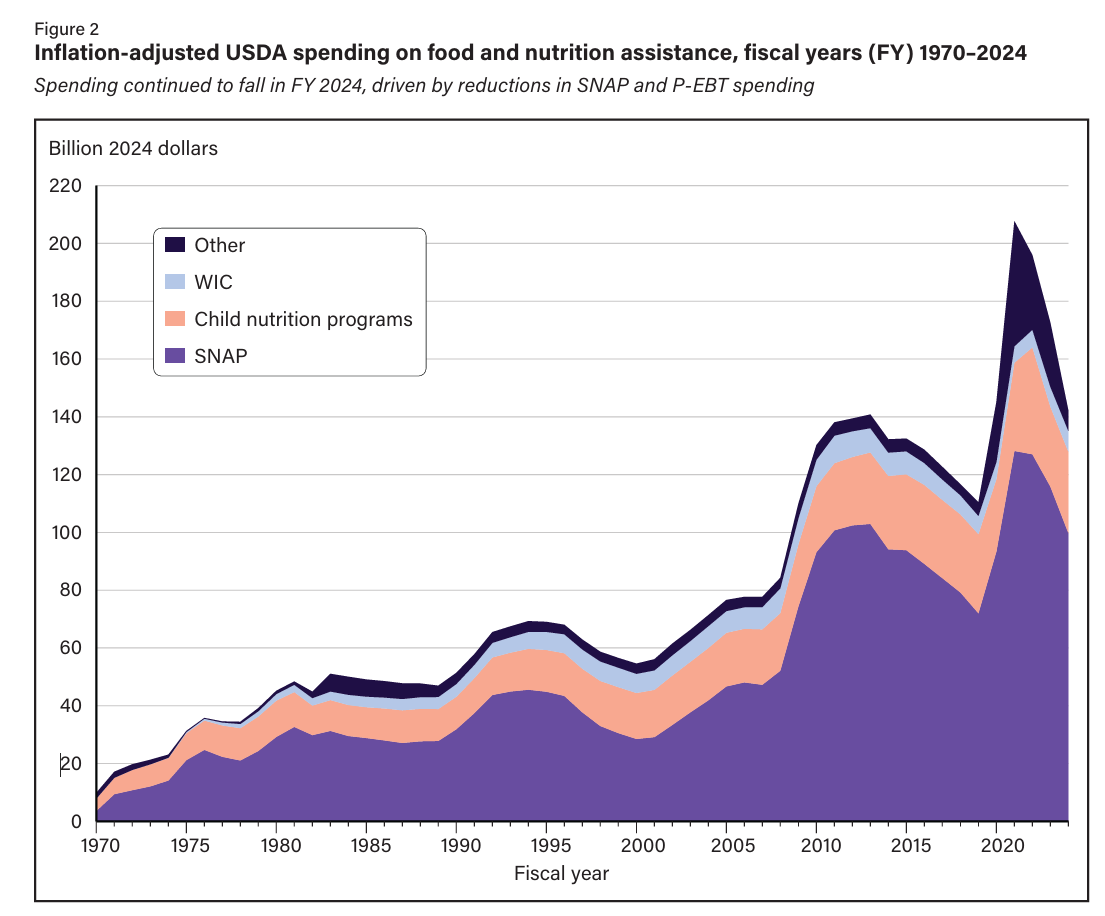

Happy U.S. Navy Day for those who celebrate.

A related book for American minorities, i.e., the minority of Americans who pay federal income tax… Fat Leonard: How One Man Bribed, Bilked, and Seduced the U.S. Navy (Craig Whitlock 2024). The book is a great argument for replacing the entire U.S. Navy with sea drones, which won’t be vulnerable to attack (nobody will cry if a drone is lost), bribery, etc. The case of Fat Leonard, and the book, expose a fundamental incompatibility between modern Americans and life aboard ships. Prior to no-fault no-shame divorce, the man on the ship and the woman back home were both coerced to be at least reasonably faithful to each other. Even in the rare cases where he didn’t fear God, the man would be shamed if he had too many girlfriends and prostitutes in foreign ports. The woman wouldn’t harvest substantial alimony and child support if she had sex with 10 different boyfriends while the husband was at sea defending our nation. The book describes what happens when all of this social infrastructure is torn down, but ship schedules that keep spouses separated for months at a time are preserved. The females left at home eventually realize that the local family court will give them whatever they want. The males at sea are thus reduced to poverty and can’t afford girlfriends, prostitutes, or new wives on whatever is left to them after paying alimony and child support. Far Leonard figured out that a man who has lost his kids, home, and wife back in the U.S. and who now has only one third of his paycheck to spend is a man who is easy to bribe.

Who was this pioneer of social psychology? Leonard Glenn Francis ran a “husbanding” business to supply ships, ideally expensive U.S. Navy warships whose officers weren’t likely to quibble about prices, with whatever they needed when in various Asian port. Much of his financial success was attributable to jihad:

The USS Cole arrived mid-morning on October 12 in Aden, an ancient Arabian port, and anchored at the mouth of the harbor. The guided-missile destroyer had transited the Suez Canal and the Red Sea and needed to stop for several hours so it could take on 220,000 gallons of fuel before continuing north into the Persian Gulf. As the crew started to eat lunch, a small red-and-white motorboat approached. The two men aboard smiled and waved as they drew close to the hulking warship. Unsuspecting sailors on the Cole waved back, thinking the skiff had come to collect trash. In fact, the two men were suicide bombers recruited by al-Qaeda and the motorboat was packed with explosives. The terrorists detonated their cargo and blew a gaping hole in the side of the Cole that almost sank the $1 billion vessel. Seventeen U.S. sailors were killed and forty-two were wounded, making it the deadliest assault on a U.S. Navy vessel in thirteen years. The attack presaged the far bigger one that al-Qaeda would inflict eleven months later with hijacked airliners. Just as the United States was unprepared for 9/11, the Navy had not foreseen that a common motorboat could torpedo one of its powerful warships. The Cole disaster instantly upended the Navy’s risk calculations for foreign port calls. Unsure of the extent of the maritime threat posed by al-Qaeda, the Navy curtailed ship visits to Yemen and other Muslim countries and upgraded force protection requirements elsewhere.

Francis devised a solution: a floating barrier that encircled a ship to prevent waterborne intruders from getting too close. The primitive contraption was merely a makeshift fence of heavy barges and pontoons linked by steel cables. But in a deft stroke of marketing, he branded it as the “Ring of Steel.” The Ring of Steel sounded impregnable and looked plausible when he showed it to Navy force protection officers. “It was impressive,” said Jim Maus, the supply officer from the USS Independence. “No little boat is going through that. Bounce off it, maybe.” The Ring of Steel was also portable. Glenn Marine could move the components from harbor to harbor and customize the perimeter to suit any ship. Shaken by the Cole bombing, the Navy grabbed the Ring of Steel as a lifeline. It didn’t have better ideas to protect its ships in Southeast Asia. Nor did it trust commercial ports or revenue-starved foreign navies to provide adequate security. The only other option was to park ships at well-guarded U.S. bases in Japan and Hawaii. With the Ring of Steel, Francis not only saved his company, but found a way to expand it. After the Cole attack, Glenn Marine became one of a handful of contractors that could meet the Navy’s enhanced force protection requirements. Most competitors in the husbanding industry were mom-and-pop operators who couldn’t or wouldn’t invest in their own floating barriers. That meant more business for Francis. “The Navy went crazy and paranoid over the Cole,” recalled Commander David Kapaun, an operations officer based in Singapore at the time. “Leonard jumped on that like you wouldn’t believe.”

There was also a virtuous interaction between Navy tradition and jihad:

He knew if he wined and dined the Americans, they were unlikely to question his exorbitant fees, including for the Ring of Steel, which cost between $50,000 to $100,000 per day. “Everybody had to use the Ring of Steel,” he recalled. “So literally, the military’s force protection became the golden goose for me.” For ship captains, no price was too high to protect their crews, not to mention their careers. The Navy held them accountable for everything that happened on their watch, regardless of whether they were personally responsible. If a low-ranking seaman screwed up a task that led to a serious accident, the Navy disciplined the commanding officer on the grounds that he or she had failed to ensure the sailor was properly trained and supervised. The Navy upheld that unforgiving standard after the attack on the Cole. A high-level investigation concluded the Cole was “a well-trained, well-led and highly capable ship” and that the skipper, Commander Kirk Lippold, was not at fault. Intelligence reporting had also failed to detect any threats in advance of the visit to Aden. But the Navy nonetheless blocked Lippold from promotion and forced him to retire—Pentagon officials and members of Congress decided someone needed to be held accountable for the disaster. Many commanding officers thought the Navy and Congress treated Lippold unfairly, but the message resonated: Take every precaution. As a result, few ship captains were willing to risk a port visit without the Ring of Steel, no matter the expense—particularly after 9/11 demonstrated that al-Qaeda’s attack on the Cole was not an isolated event. Terrorist threats spread to Southeast Asia. In October 2002, an al-Qaeda affiliate bombed Bali’s tourist districts, killing 202 people. Seven Americans died and the U.S. consulate was damaged. The Navy reduced its visits to Indonesia, but demand for the Ring of Steel soared in other ports. Glenn Defense’s bottom line soared with it.

An officer would be demoted or fired if something bad happened to the ship, but there were no consequences for wasting taxpayer funds.

The book has some inspiration for upgrading your next party:

With his shirt untucked and his stomach hanging out, an inebriated Leonard Francis lay atop a banquet table at one of the most exclusive restaurants in Singapore. A prostitute hand-fed him leftover morsels from the $30,000 feast he was hosting. Around the table, his American guests—about two dozen U.S. Navy and Marine Corps personnel—puffed Cohiba cigars from Cuba and swilled Dom Pérignon while a gaggle of young women massaged their necks. One Navy officer present said the scene resembled a “Roman orgy.” For the five-hour party with his American customers, Francis had rented Jaan, a Michelin-starred restaurant on the seventieth floor of a luxury hotel. Through plate-glass windows, the private dining room boasted spectacular views of the Singapore skyline and, in the distance, the twinkling lights of ships on the South China Sea. But the sights inside the restaurant that evening made an even more indelible impression. One prostitute flashed her breasts at Rear Admiral Robert Conway Jr., the commanding officer of the USS Peleliu expeditionary strike group. Colonel Michael Regner, the normally rigid commander of the strike group’s 2,200 Marines, mouthed the words to “Y.M.C.A” while a band played the disco hit. One Navy captain was spotted French-kissing a prostitute. As the spectacle unfolded, a few officers watched slack-jawed, unsure how to respond to their superiors’ conduct. The rest had the time of their lives.

U.S. Navy officers weren’t supposed to accept bribes, whether cash or fancy dinners/fancy women, but the service came up with a workaround whereby captains and admirals would pay $50 to Fat Leonard’s company as their share of a meal that cost far more (remember that all of the numbers in the book are in pre-Biden dollars):

The “Valentine’s Cheer” celebration unfolded the next night in a balloon-decorated banquet room at Petrus, the Michelin-starred restaurant on the top floor of the Shangri-La Hotel. About twenty people attended, including a half-dozen Navy spouses who received floral bouquets and fancy chocolates from Glenn Defense. The avant-garde menu showcased elements of molecular gastronomy, including champagne espuma and coral powder made from dehydrated lobster roe. The Americans and their genial host also ate Oscietra caviar, gobbled slices of bread topped with foie gras and Wagyu beef, and savored Périgord black truffle, a rare French fungus that is to be served within three days of harvesting. A different wine accompanied each of the eight courses. “It was one of the most extravagant things I’ve ever seen,” recalled Lieutenant Commander Edmond Aruffo, an officer on the Blue Ridge. “I didn’t know people lived like that.”

Some officers and civilian Navy employees took cash instead of or in addition to fine living:

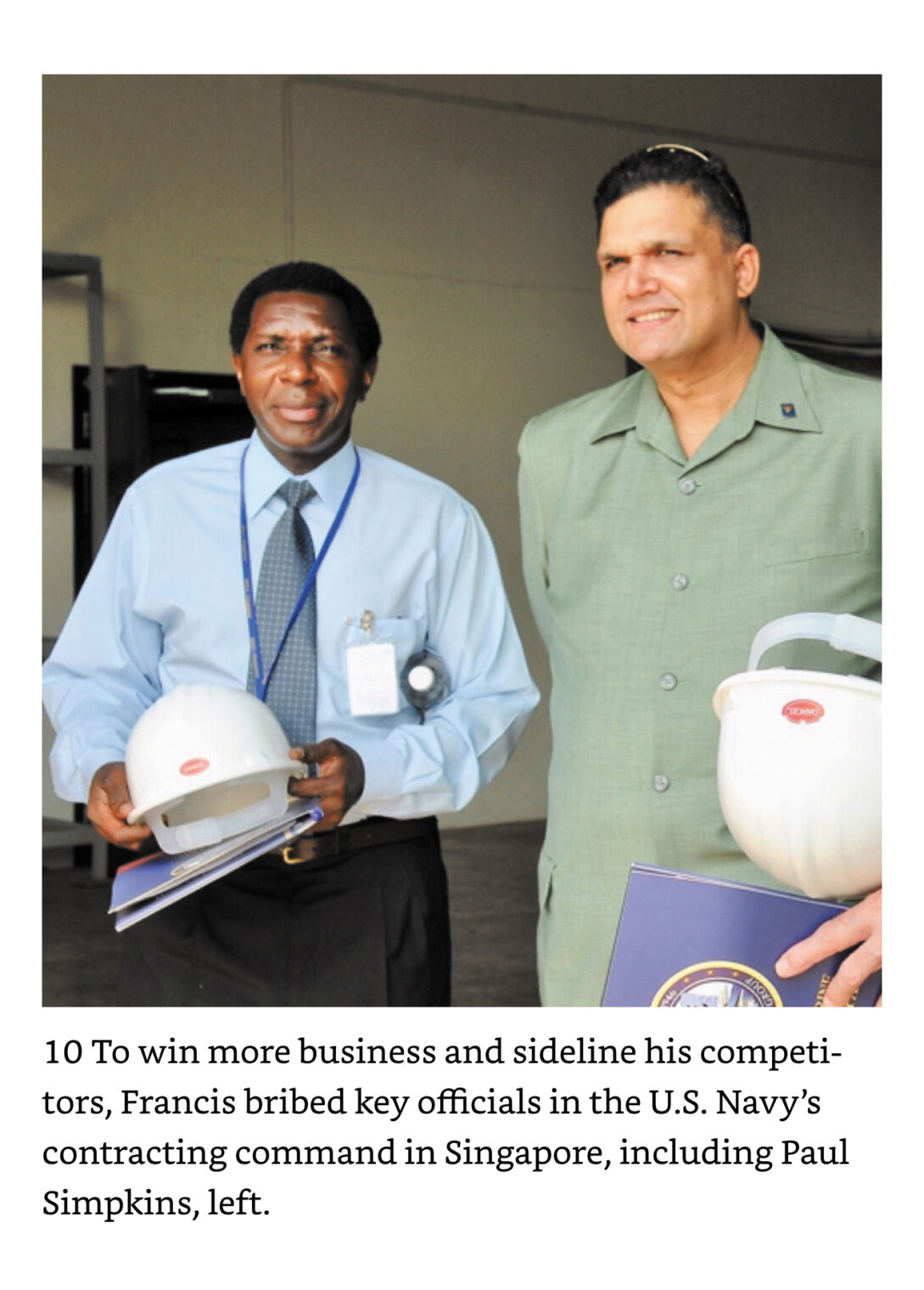

The senior civilian supervisor at the Naval Regional Contracting Center in Singapore was Paul Simpkins, a fifty-one-year-old South Carolinian who had specialized in the fine print of defense contracts since he was a teenager. He served more than two decades as a uniformed contracting officer in the Air Force and attained the rank of master sergeant before retiring from active duty in 1994. He then filled a variety of civilian contracting jobs for the Marines and Navy before arriving in Singapore in 2005 for a two-year assignment. In his new job, he held the power to award millions of dollars in federal contracts. The child of a single mother, Simpkins grew up poor in the South. The military provided him with a steady career, if not riches, and opportunities to live all over the world. A slim, fastidious man, he was an introvert who rarely socialized with coworkers or discussed his personal life. Few knew that he had been married five times or that his current wife had cancer and was living in Japan. Even fewer knew he was cheating on her with a Chinese girlfriend who would eventually become spouse number six.

After several conversations, Simpkins cut to the chase: What was in it for him? Francis was pleased. This was a man he could do business with. Ordinarily, he devoted months or years to grooming Navy contacts, but occasionally he got lucky and found someone who was unabashedly greedy. During a subsequent visit to the hotel bar, Francis said he handed over an envelope containing a stack of $100 bills—$50,000 worth. Simpkins smiled, allegedly taking the bribe and sliding it into his jacket pocket.

… Reagan—he bribed Simpkins with an additional $350,000 by wiring the money to a Japanese bank account in the name of his cancer-stricken wife. As an added sweetener, he said, he provided Simpkins with prostitutes on more than ten occasions.

Here’s the government worker and Fat Leonard:

The money paid to Simpkins and others was a great investment:

David Schaus, the lieutenant in the Ship Support Office who had feuded with Francis over the Reagan’s wastewater bill, devised a

Full post, including comments