Continuing our look at Great Society: A New History, a book that chronicles the biggest shift since the 1930s in Americans’ relationship to government. (See Great Society history lesson II also.)

The idea of reparations is not a new one…

In 1963 the Urban League’s Whitney M. Young had proposed a Marshall Plan for black Americans, including direct payments to poor families to lift them over the poverty line. Thomas Sowell, a graduate student, was concentrating on his PhD, an essay on the pre-Keynesian economist Jean-Baptiste Say. But Young’s idea irked Sowell so much that he’d written a letter to the New York Times. The reaction to such a Marshall Plan, Sowell wrote, or to any other offer, would be the same from black Americans as it was from whites. “People who have been trying for years to tell others that Negroes are basically no different from anybody else,” Sowell said, “should not themselves lose sight of the fact that Negroes are just like everybody else in wanting something for nothing.”

White people loved higher minimum wages just as much back then as they do now:

Black and white youth unemployment had run about the same until the middle of the 1950s, 8 to 11 percent. But when Congress raised the federal minimum wage by a third in 1956, unemployment rose far higher among black teenagers than among whites, to 25 percent. … the economist Milton Friedman was reaching a conclusion: those who were supposed to benefit from a minimum wage were nearly always actually hurt, as “the intended beneficiaries are not employed at all.” Friedman the following year would slam the minimum wage as “the most anti-Negro law on our statute books.”

Then as now, government handouts ideally are about the same as the median wage:

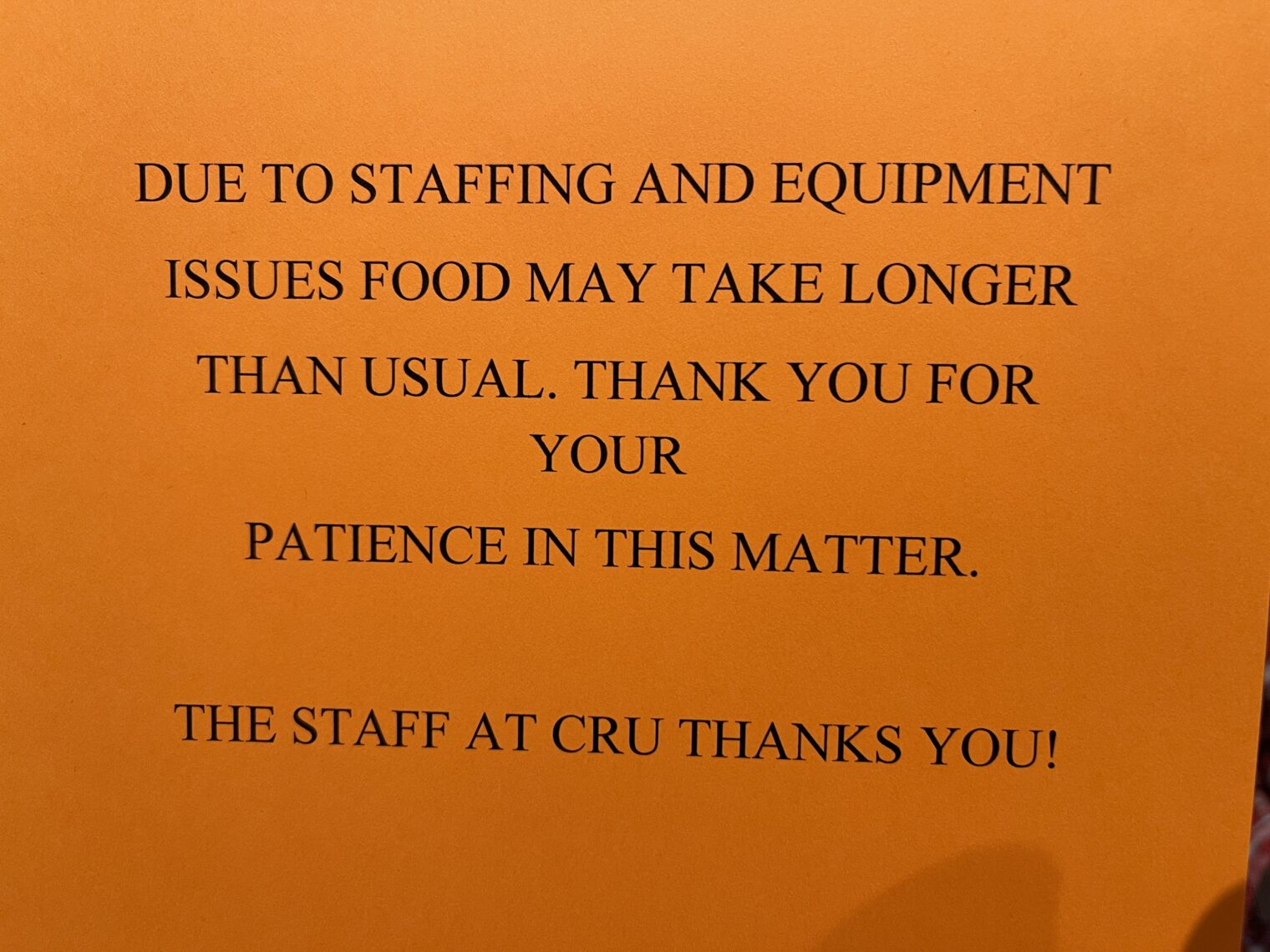

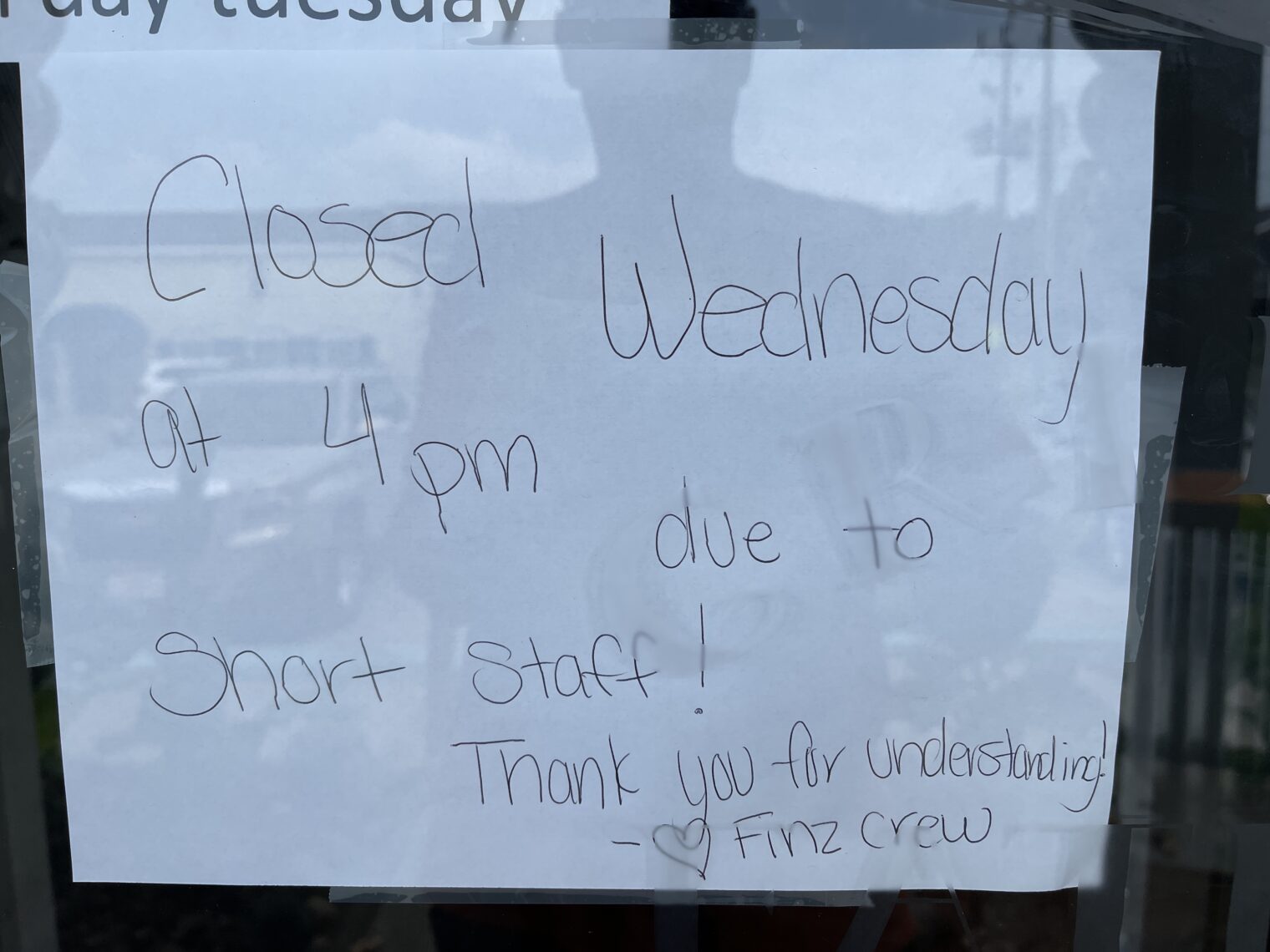

But the newly generous War on Poverty welfare benefits actually encouraged men not to work, adding to the ranks of unemployed. With the average family welfare check between $ 177 and $ 238 a month, and wages at $ 220, the commission concluded that “the financial incentive to find work may be either negative or non-existent.”

(See “The $600 Unemployment Booster Shot, State by State” (NYT) and “Work Versus Welfare” (CATO, 2013))

Certainly there shouldn’t be a housing shortage in the U.S. at this point…

But the scaling and the speedups were also evident at home, in the new HUD building, and a nationwide building program. For housing, Johnson promised $7.5 billion, more than nine times the poverty program’s annual budget that first year. The American people were, Johnson said, “strong enough to pursue our goals in the rest of the world while still building a Great Society here at home.” In 1966, everything could be, had to be, big. Even before Watts, Washington had made up its collective mind to put its formidable shoulder into a second Great Society drive, housing. Since Watts, that commitment had only hardened. The Administration would supplement, and sometimes steamroller, its flawed program, community action, with construction. Nobody could disapprove of infrastructure improvement, politicians told one another.

And we should have all of the infrastructure that we need too. at least in the cities that Big Government favors:

Johnson laid out his second Great Society in his State of the Union address in January. The president would support construction everywhere. More than $ 2 billion of the funds would go to rebuilding cities. The president would also follow the Reuther plan for Demonstration Cities, “and rebuild completely, on a scale never before attempted, entire central and slum areas.” Working together with private enterprise—this time, Johnson did not emphasize municipal governments—the federal government would rebuild areas of up to 100,000 people. Johnson would add shops, parks, and hospitals around the new housing. In the same speech, the president asked Congress to pass legislation funding rent assistance. Taken together, the results, the president hoped, would be something similar to what his old community action drive had sought: “a flourishing community where our people can come to live the good life.” This whole second project would resemble something like what the United States had done in rebuilding Europe under the Marshall Plan. Eager to make Detroit the star of the new campaign, Reuther rounded up support in Michigan. Reuther wrote to Mayor Cavanagh to encourage him: “Detroit can become an exciting and shining model of a 20th century city in the Great Society.” Reuther promised Cavanagh that they could work together in a new institution, the Detroit Citizens Development Authority.

Without the gold standard, a democracy will always vote itself into insolvency or hyperinflation, according to Alan Greenspan, 1960s version:

Greenspan wrote that American overspending wasn’t strength or a wartime phenomenon; it was predictable. A welfare state, which was what the United States had become, always overcommitted. “The welfare statists,” Greenspan said, were always “quick to recognize that if they wished to retain power, the amount of taxation had to be limited and they had to resort to programs of massive deficit spending, i.e. they had to borrow money, by issuing government bonds. . . . Gold stands in the way of this insidious process. It stands as a protector of property rights. If one grasps this, one has no difficulty in understanding the statists’ antagonism toward the gold standard.”

Not every Black American meekly agrees with white saviors:

On January 18, 1968, the day after the State of the Union, Mrs. Johnson received a reminder that many Americans could not agree. The First Lady hosted a “Women Do-ers” lunch at the White House, with fifty guests. Among them was the black star Eartha Kitt, whom Americans knew as an actress, singer, activist, and star on Batman, where Kitt played Catwoman. Johnson himself entered mid-lunch to address the group. The president spoke about expanding Social Security. Kitt spoke up, too, speaking not about entitlements, but noting that “because taxes are so heavy, both parents have to work.” Johnson was taken aback, and announced he had just seen through the passage of a Social Security bill that allotted millions for day care. A “non sequitur” was how Kitt characterized Johnson’s reply. Kitt so intimidated the president that he fled the room, saying such questions were “something for women to discuss here.”

When Nixon takes over, the machinery put in place by Johnson hums at an accelerated pace.

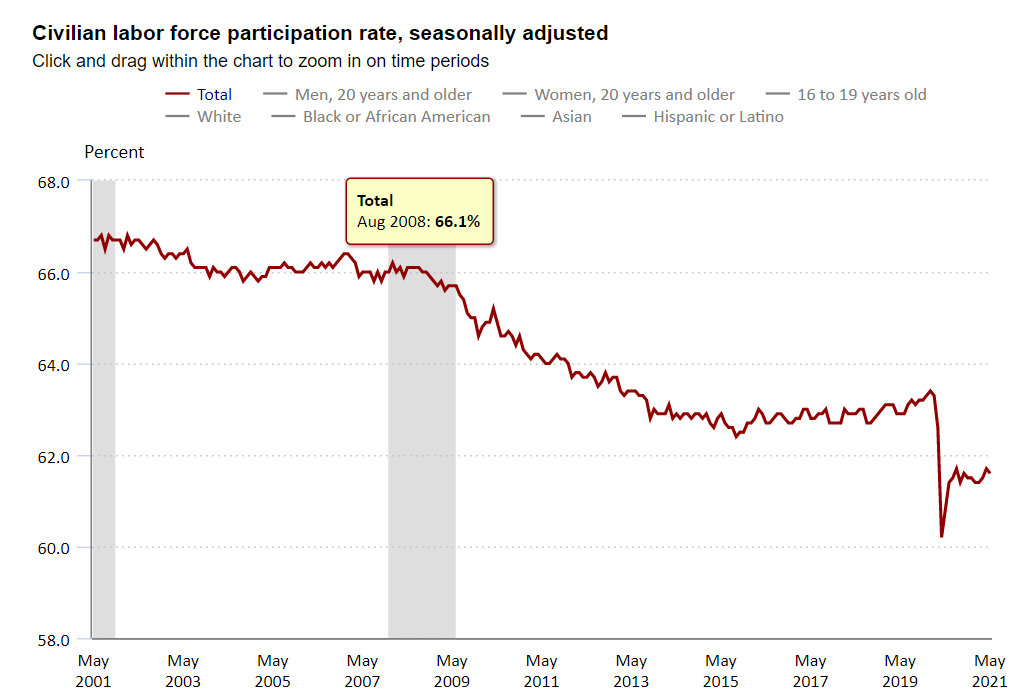

Despite the historically low unemployment rate, federal welfare payments were exploding. In one of the first of a number of long, careful memos that Moynihan penned to his future boss, he offered New York City as an example. New York’s welfare payments alone amounted to $ 2 billion, double the once huge-sounding initial budget for the War on Poverty. Nationally, spending for the old welfare system had risen by half in just two years, and spending for the disabled was up by 26 percent in the same period.

The Democrats have to top whatever the Republicans promise:

Rather than going along with Nixon, McGovern, perhaps already thinking of the presidential race in 1972, was readying his own plan, payments of $ 600 per child for all families below the middle class, a program that would cost multiples of the Nixon scheme. Hubert Humphrey, momentarily shocked, noted that the McGovern plan would place close to half of the United States on welfare. A new lobby, social workers, also made its objections known. President Kennedy’s and Moynihan’s Executive Order 10988 long ago had transformed once weak public-sector unions into titans. The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, one of those newly powerful unions, counted thirty thousand social workers among its members. Now social workers rose up in blunt defense: “This legislation threatens to eliminate the jobs of our people,” said the union spokesman.

The book describes the importance of Goldberg v. Kelly, a case that turned handouts into “entitlements” akin to a property right.

How about three weeks to flatten the curve turning into 16 months of restrictions? Is that new?

Pete Peterson had supported the temporary income tax, but when, later, Connally and Nixon advocated keeping the tax in place through the 1972 election year, Peterson was, by his own description, “aghast.” Doubly infuriating was that Nixon broke a promise, by making something he’d labeled “temporary” seemingly permanent. Herb Stein, the most reflective in the group, wrote several essays about Camp David. “Even now, I am amazed to think of how little we looked ahead during that exciting weekend at Camp David when we (the president, really) made those big decisions,” he wrote in 1996. “We were going to freeze wages and prices for ninety days. What would happen after the ninety days? I don’t remember any discussion of that.” As it turned out, Stein noted, some of the freezes lasted more like a thousand days.

As with a lot of history books, this work is interesting for showing the reader how little has changed. Americans still have the same issues, e.g., some people don’t want to work at all and others have a level of skill that is not high enough to command what we would call a “living wage.” The arguments on all sides are more or less the same as today (remember that universal basic income was tried in 1970; see Long-term effects of short-term free cash (guaranteed minimum income experiments)).

Probably the biggest change from the 1960s is immigration. The architects of our welfare state imagined that the U.S. had a fixed supply of uneducated badly housed poor people. The $billions in tax dollars would lift each of those people out of poverty via education and job training, fresh public housing, new infrastructure, etc. After that had been accomplished, there wouldn’t be any more poor people. It didn’t occur to them that 1 million low-skill people, destined to be poor in an economy for which they lacked the job and language skills, would walk across the border each year. Certainly they didn’t imagine that their creation of the welfare state itself would attract low-skill migrants, for whom the welfare state removes all risk of migration (if employers don’t want a migrant or the migrant does not enjoy working, public housing, health care, food stamps, etc. are all there as an alternative to work).

Full post, including comments