FastCompany says that Apple and Google will kill Twitter by removing the app from their respective monopoly stores if they see anything on Twitter that they don’t like.

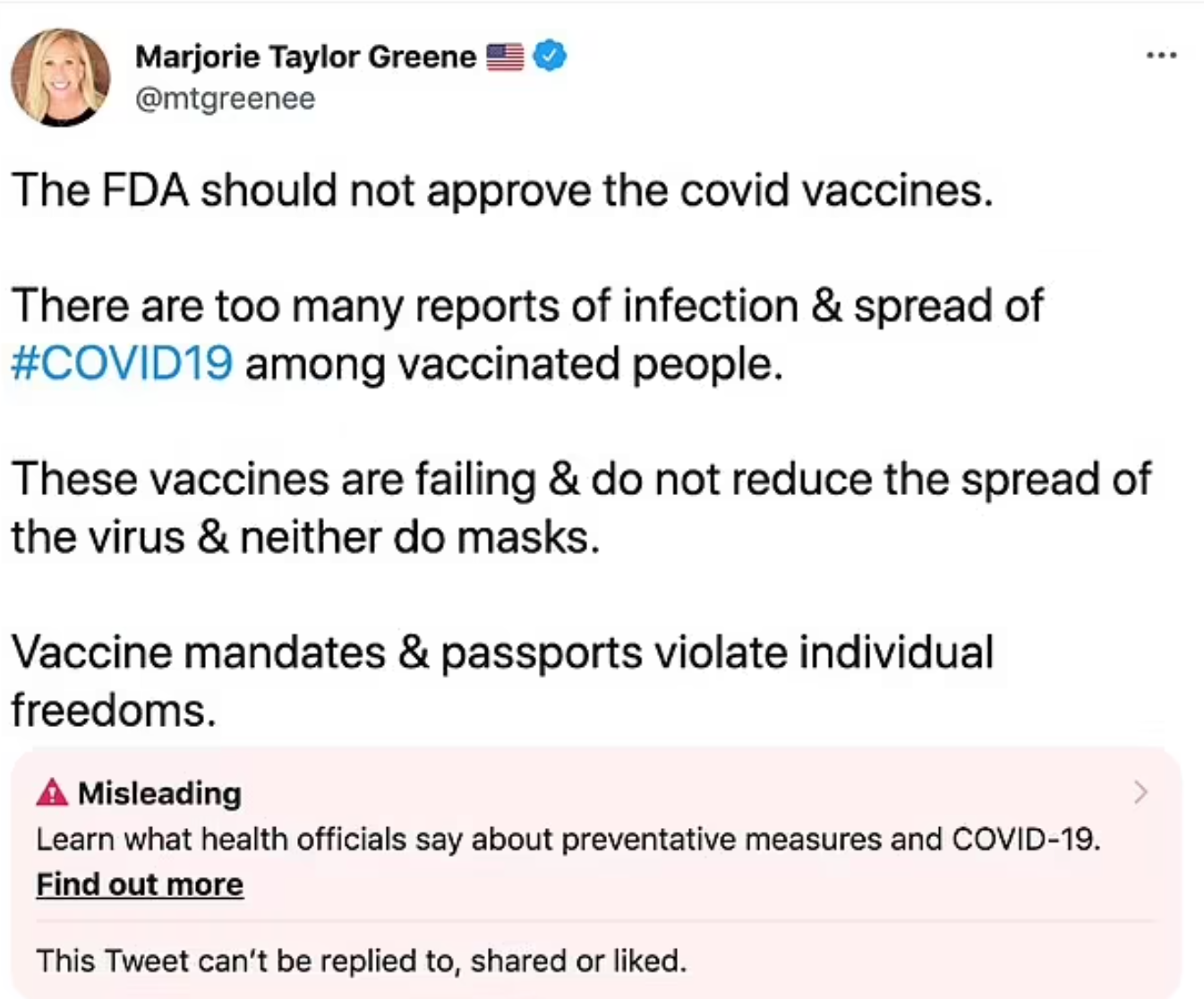

Twitter, obviously, will remove anything and anyone that the company deems objectionable. Historically this was people who did not follow the Democratic Party line, e.g., the New York Post for the Hunter Biden laptop story.

“Twitter must comply with Europe’s platform rules, EU digital chief warns Musk in virtual meeting” (CNN Business):

… the social media platform must take significant steps to comply with EU content moderation laws, …

Twitter has “huge work ahead” to meet its obligations under the Digital Services Act, Europe’s new platform regulation, said Thierry Breton, the EU’s digital chief, in a readout of his meeting with Musk.

“Twitter will have to implement transparent user policies, significantly reinforce content moderation and protect freedom of speech, tackle disinformation with resolve, and limit targeted advertising,” Breton said…

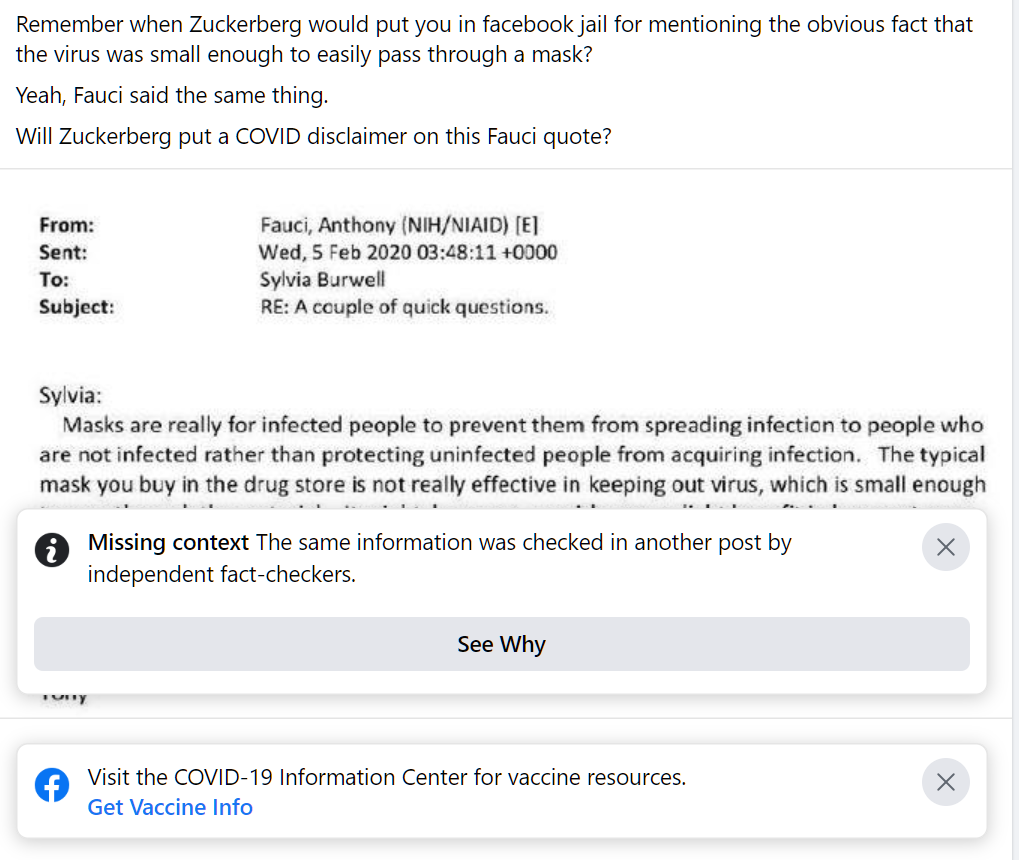

I would love to learn about this law! To “protect freedom of speech”, it is necessary for a service to prevent anyone from speaking in a way that the European Union bureaucrats don’t like (“reinforce content moderation”)? And who decides what is “disinformation” that violates EU law? Sticking with the Hunter Biden laptop story, above, all of the Washington, D.C. expert insiders said that it was disinformation. “Hunter Biden story is Russian disinfo, dozens of former intel officials say” (Politico, just before the 2020 election on 10/19/2020):

More than 50 former senior intelligence officials have signed on to a letter outlining their belief that the recent disclosure of emails allegedly belonging to Joe Biden’s son “has all the classic earmarks of a Russian information operation.”

The letter, signed on Monday, centers around a batch of documents released by the New York Post last week that purport to tie the Democratic nominee to his son Hunter’s business dealings.

While the letter’s signatories presented no new evidence, they said their national security experience had made them “deeply suspicious that the Russian government played a significant role in this case” and cited several elements of the story that suggested the Kremlin’s hand at work.

While there has been no immediate indication of Russian involvement in the release of emails the Post obtained, its general thrust mirrors a narrative that U.S. intelligence agencies have described as part of an active Russian disinformation effort aimed at denigrating Biden’s candidacy.

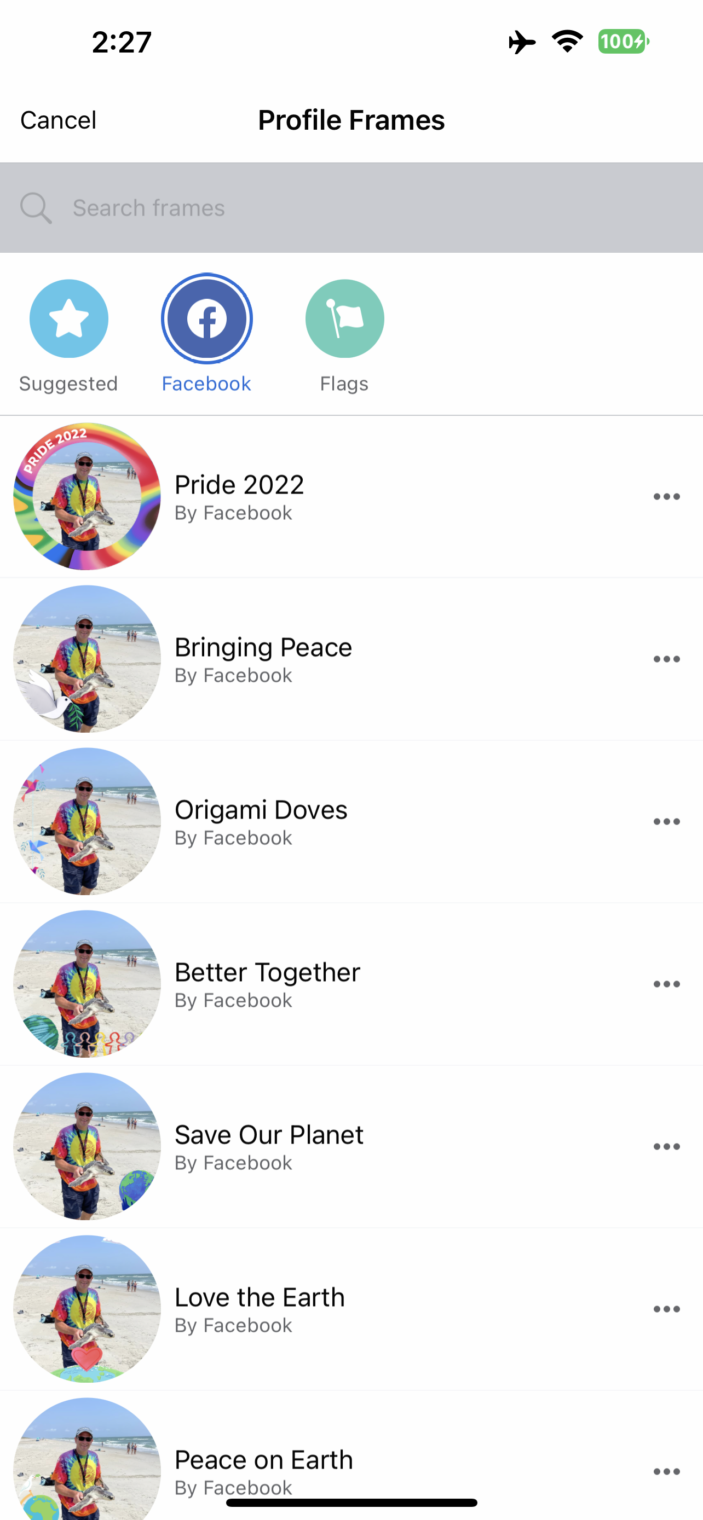

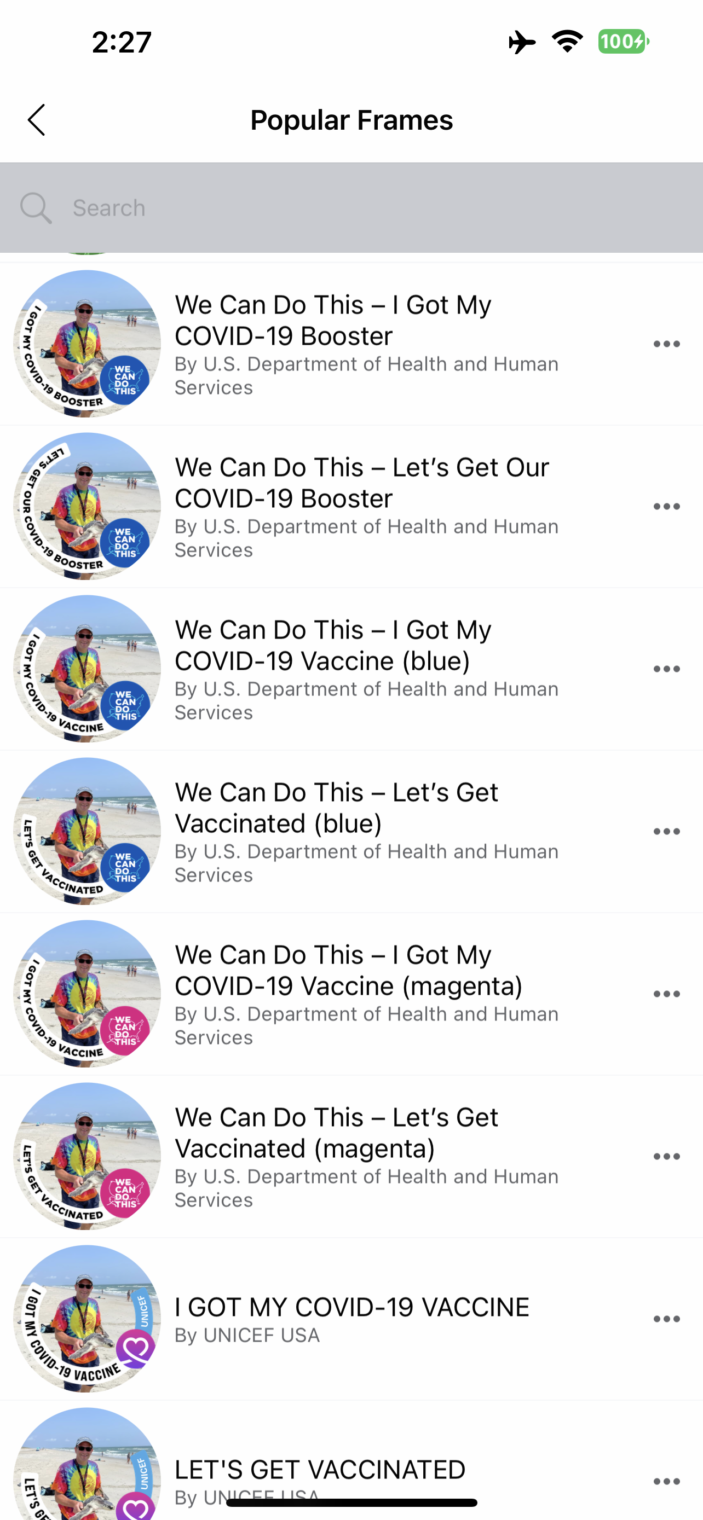

Facebook hasn’t faced the same scrutiny, perhaps because they are still censoring in accordance with the ruling politicians’ wishes. But they could also be taken down by the smartphone duopoly or the EU.

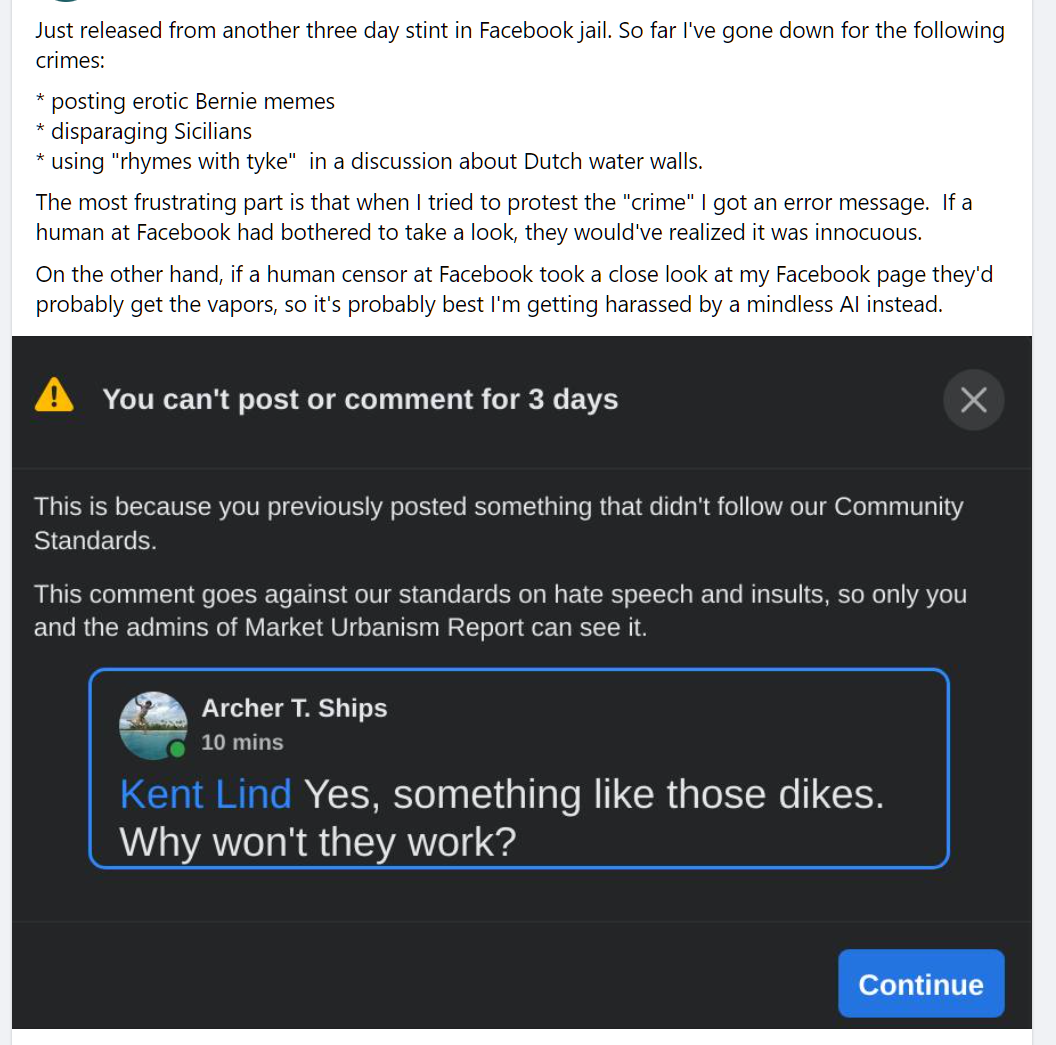

In summary, there are now at least four filters through which content must pass before it can be distributed via the only practical modern means of reaching a substantial number of people. Folks in China might have more practical freedom of speech because there are only two filters: the operator of a service and the government.

This is an interesting illustration of how the early Internet nerds’ predictions turned out to be 100 percent wrong. None of them would have imagined a world in which there was no practical way to sell a book if a single bookstore (Amazon) didn’t like it and in which multiple bureaucracies exercised veto power over the online existence of any individual user and his or her (there was just two gender IDs back then) speech.

My question is why the same standards aren’t applied to web sites and email. Google and Apple can program their browsers to reject attempts to visit web sites that contain disinformation, e.g., that COVID vaccines do not prevent infection and transmission. Or at least augment web pages with context, as Twitter and Facebook already do. Google and Apple also control email systems. Why allow Deplorables to share misinformation and disinformation via email? The idea is that the companies, out of the goodness of their corporate hearts, will ensure online safety when on Facebook and Twitter, but will make zero attempt to prevent people from being led astray when reading email? How does that make sense? At a minimum, shouldn’t Gmail add context? If a personal friend gets an email from Rochelle Walensky about becoming sick with COVID a month after receiving the bivalent booster, Gmail could display “MISSING CONTEXT. The latest bivalent COVID boosters have been proven to protect against all SARS-CoV-2 variants. Visit cdc.gov for more information about COVID.” If someone is reading about how New York State is #1 in the nation in percent of residents’ income taxed away to fund state and local government, Safari could add a banner “Visit www.governor.ny.gov to learn how New York provides abortion care and protects you from gun violence with the taxes that you pay.”

Sculpture from the Louvre below titled “EU online safety expert deplatforms Nick Fuentes.”

Full post, including comments