EAA AirVenture (“Oshkosh”) opens today so it is time for an aviation-themed post…

The F-35 played a role early in the recent fighting between Israel and Iran, but after air defenses were neutralized, Israel bombed targets using older non-stealth fighters. From Topgun: An American Story, by Dan Pederson, one of the founders of the Navy Fighter Weapons School:

One question deserves to be whether we even need such expensive capabilities as stealth in our planes. I’m not so sure. New sensors that are within the current capability of Russia and China to field don’t even use radar waves. These infrared search-and-track devices can detect the friction heat of an aircraft’s skin moving through the atmosphere, as well as disturbances in airflow.

Maybe the cost-effective approach is to use drones to perform all of the attacks against an adversary’s air defenses and then send in legacy aircraft? The author says that we can’t afford to provide human fighter pilots with enough combat hours to stay proficient, which is another great argument for AI/drones:

At Topgun in my day, a pilot had to log a minimum of thirty-five to forty flight hours every month to be considered combat-ready. This is no longer possible. As the F-35 continues to swallow up the money available to naval aviation, the low rate of production all but ensures that our pilots will not soon gain the flight hours that they need to get good. For the past few years Super Hornet pilots have been getting just ten to twelve hours per month between deployments—barely enough to learn to fly the jet safely. The F-35 has far less availability. Its pilots have to rely on simulators to make up the deficit. Its cost per flight hour is exorbitant.

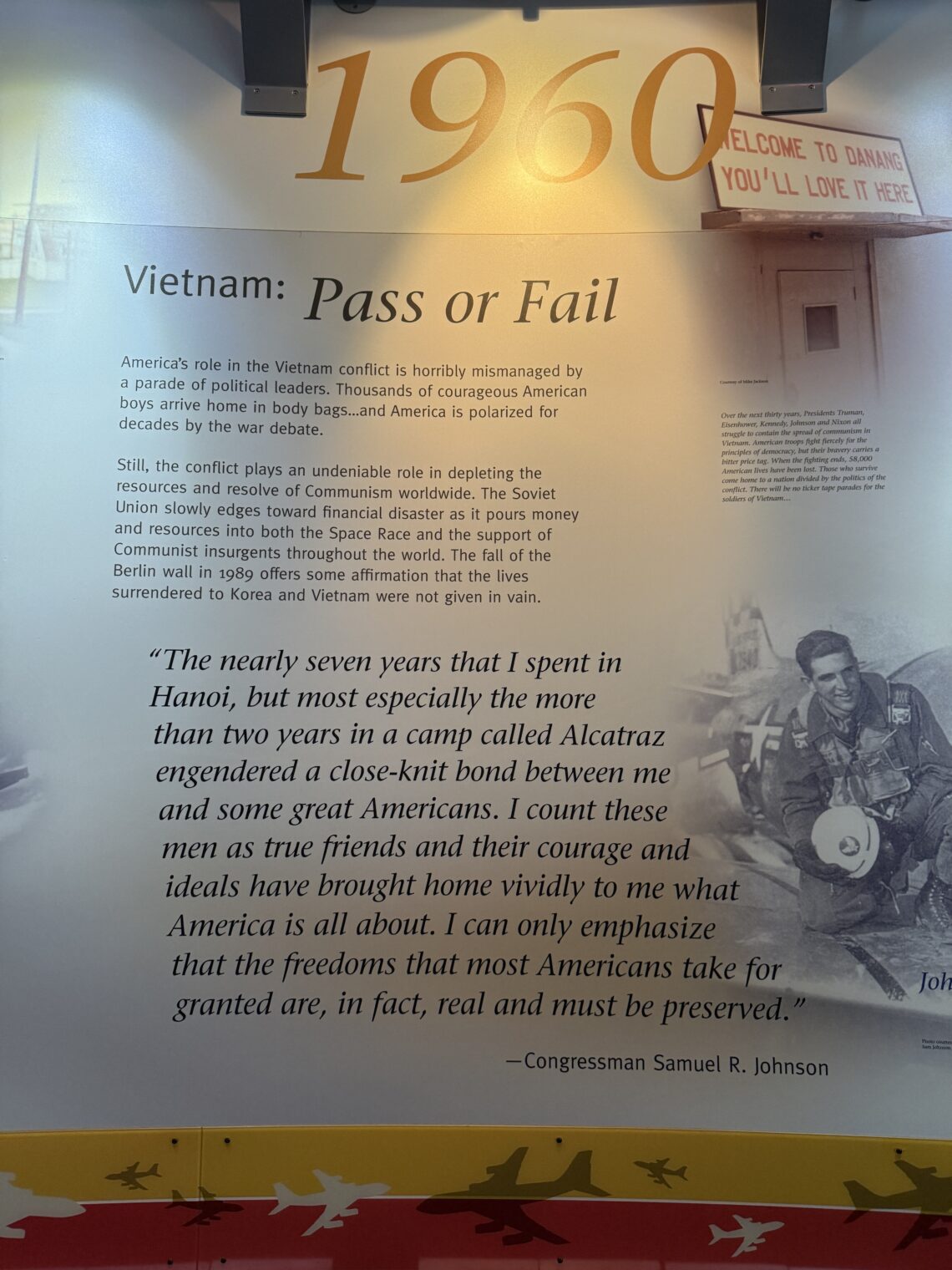

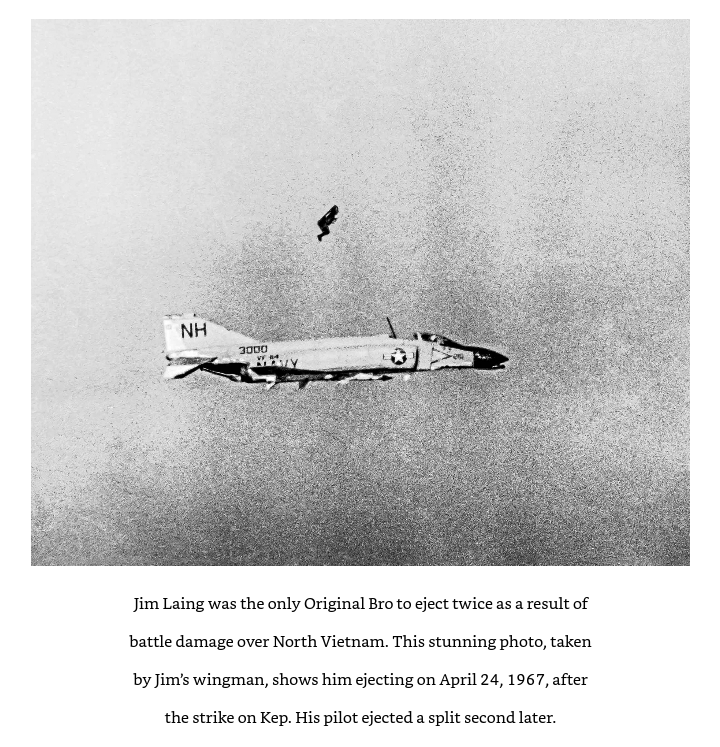

There are quite a few reminders in the book of the high cost of war against a near-peer, e.g., in Vietnam:

What else is in the book? Here’s a passage that can be used by the pro-open-borders folks:

My parents were immigrants and I was a first-generation American. Dad, named Orla or Ole, was born in Denmark in 1912 and his parents, Olaf and Mary Pedersen, immigrated the next year. My mother, Henrietta, was one of three beautiful sisters from the Isle of Man.

Immigrants, regardless of which society they come from, make the best Americans.

Serving in the Navy is a bad idea for anyone who wants to be a parent:

One night I was aboard ship, ready to take my first ship command, when I got a phone call. Somehow my eight-year-old son had found my direct number. I answered. He was crying. He begged me not to leave. “Please, Dad. Come back… everyone else has a dad home with them. I don’t.”

It worked okay, apparently, in the pre-no-fault (unilateral) divorce world, but it seems that Navy wives eventually turn plaintiff if the officer-pilot doesn’t get killed in an accident or combat. The author himself seems to have been sued by two wives:

My first marriage did not survive the many deployments of the 1970s. Being gone so much finally drove a wedge between us that could not be removed. I married a second time while serving in surface ships. Ever the optimist, I guess. It wasn’t meant to be.

The Vietnam war wasn’t winnable from the air for a variety of reasons:

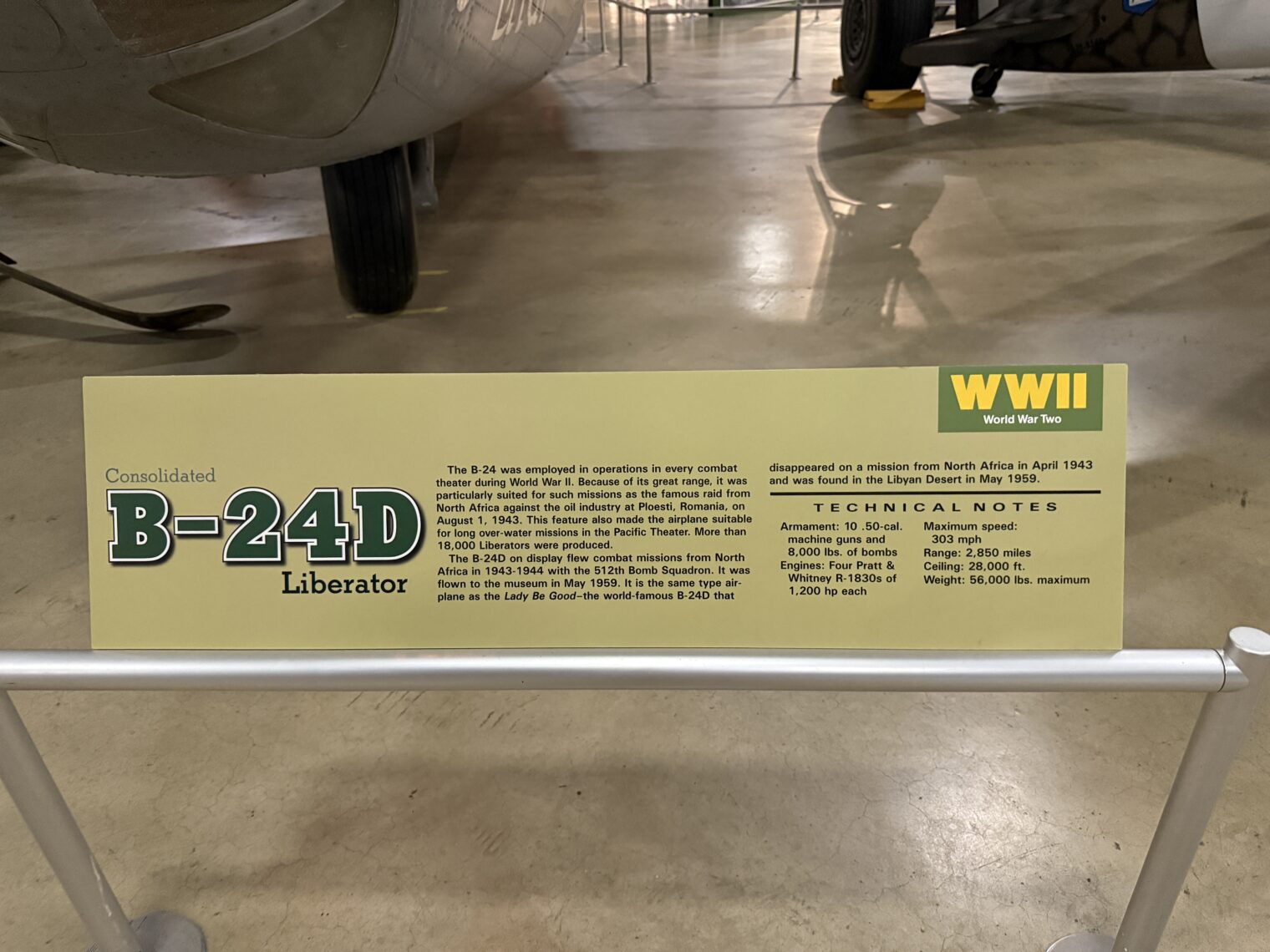

Afraid of escalating the war, the Johnson administration refused to sanction attacks on Haiphong Harbor or the shipping there. As we started flying missions up north, we would pass near those cargo ships as they waited their turn to offload at the docks. We could see their decks crammed with weatherized MiGs and surface-to-air missiles that would shortly be used against us. But we couldn’t hit them. And we couldn’t mine the harbor, either. What a tragedy. The simple execution of an off-the-shelf aerial mining plan, long before perfected during World War II and carried out in three days, could have shut down that big port—the only one of its kind in North Vietnam. But the word from the White House was no. Those big surface-to-air missiles, as large as telephone poles, would spear up into the sky after our aircraft, homing on their radar signatures. They took a heavy toll. We could seldom bomb the missile sites for fear we might kill their Russian advisers.

When the North Vietnamese began flying Russian-and Chinese-built MiG fighters, the Navy and Air Force asked Washington for permission to bomb their airfields. The request was denied. Categories of targets that could not be struck under any circumstances included dams, hydroelectric plants, fishing boats, sampans, and houseboats. They also included, significantly, populated areas. Seeing the military value of these restrictions, the North Vietnamese placed most of their SAM support facilities and other valuable cargo near Hanoi and Haiphong—places we were forbidden to strike. The airfields around Hanoi became sanctuaries for the MiGs; the commander in chief of U.S. Pacific Command, Admiral Ulysses S. Grant Sharp, who had overall responsibility for the air war, urged the Joint Chiefs of Staff to lift the crippling restrictions. Meanwhile, the enemy fighter pilots could sit on their runways in their planes without fear of attack, waiting to scramble when our bombers showed up.

Postwar research suggests that Hanoi occasionally received updated target lists about the same time we did on Yankee Station. Our own State Department passed the list to North Vietnamese via the Swiss government in hopes that Hanoi would evacuate civilians from the target areas. Of course they cared little about that. They simply used the valuable intel to duck the next onslaught, moving MiGs out of harm’s way and bolstering antiaircraft artillery and surface-to-air missile batteries in the target areas for good measure. Destroying the MiGs on the ground proved difficult enough, but we were also ordered not to attack them in the air unless they could be visually identified and posed a direct threat.

Those rules of engagement negated the way we had trained to fight in the air. The value of our F-4 Phantoms was their ability to destroy enemy planes from beyond visual range. The AIM-7 Sparrow was the ultimate expression of that new way of fighting. Track and lock with the radar system, loose the missile from ten miles out, and say goodbye to a MiG. This is how the Navy trained us to fight. We abandoned dogfight training because of the Navy’s faith in missile technology. Most of our aircrews didn’t know how to fight any other way. Yet our own rules of engagement kept us from using what we were taught. The rules of engagement specifically prohibited firing from beyond visual range. To shoot a missile at an aircraft, a fighter pilot first needed to visually confirm it was a MiG and not a friendly plane. The thought of inadvertent or accidental shootdown of our brothers was of course intolerable. It did happen, sadly, in the heat of combat. Yet three years along, the training squadron in California was still teaching long-range intercept tactics to the exclusion of everything else. Our training was not applicable to the air war in Vietnam.

Assumptions used in engineering turn out to be wrong:

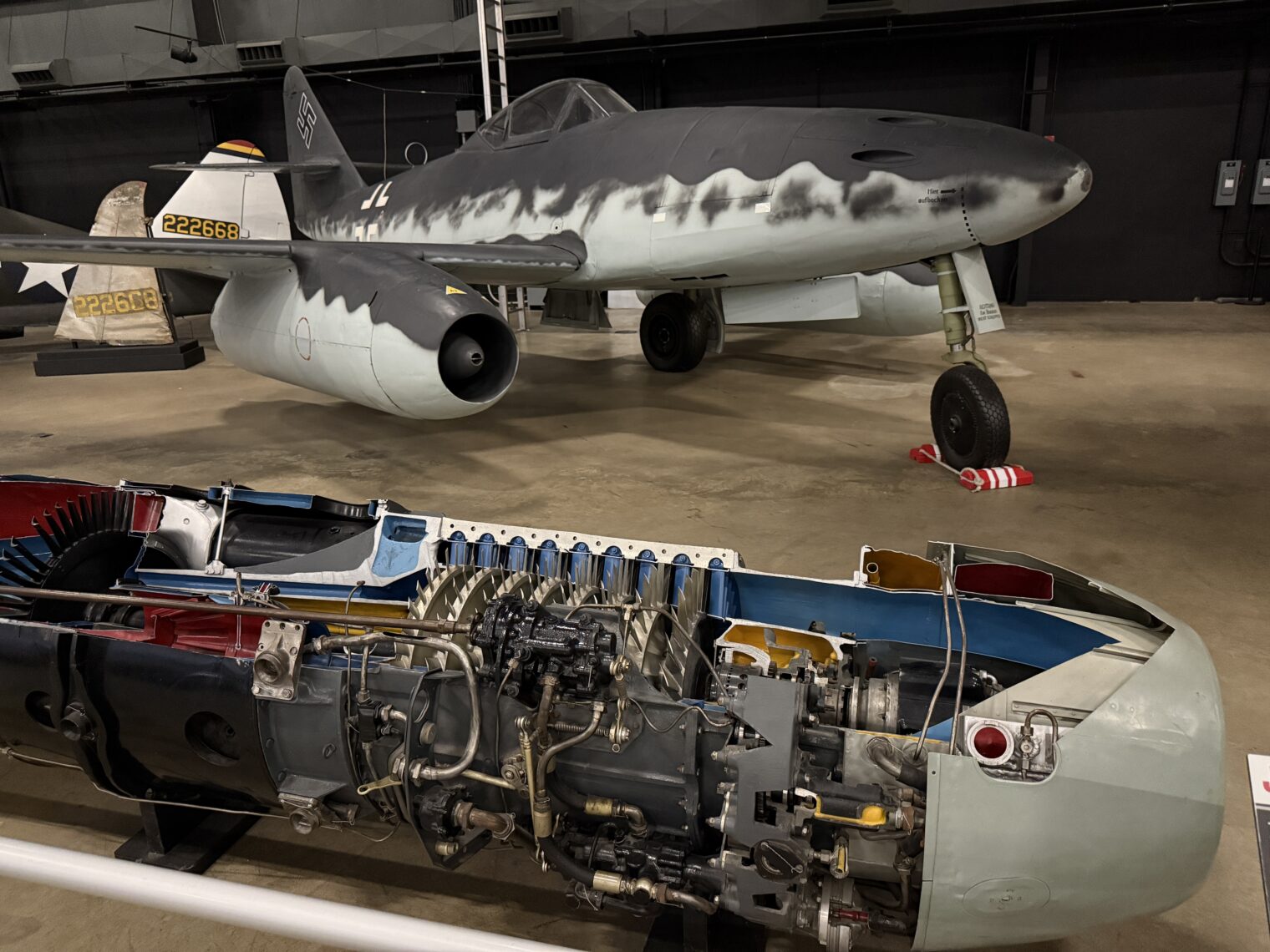

The MiG-17 was a nimble fighter armed with cannons, but no missiles. It was old school, derived from the lessons the Soviets learned in the Korean War. With such a plane, the North Vietnamese needed to get in close and track our planes with their gunsights. They would sometimes wait to open fire on us until they were within six hundred feet. Here we were, trained to knock planes down at ten miles. The F-4 carried only missiles; it did not have an internal gun because contractors and the Pentagon believed the age of the dogfight was over. We brought our expensive high tech into this knife fight in a phone booth. The result? The MiG pilots scored a lot more heavily than they should have.

And the engineering didn’t work:

Over Vietnam, our Sparrow missiles usually malfunctioned or missed. So did the AIM-9 Sidewinders. How could we not have known this prior to 1965? Well, history repeats: The weapons were so expensive that the Navy could not afford to use them in training. Live-fire shooting was done against drones flying straight and level, like an unsuspecting bomber might be caught doing. We didn’t know we had a problem until the weapons had to be deployed against fighters.

Politicians in Washington, D.C. managed to convince themselves that everything was going great:

We had to find a way to win in spite of these technical problems and political interference. Robert McNamara was a numbers guy. Under him, the Pentagon measured success in the ground war by the body count. In the air, the metric was the number of sorties flown over North Vietnam. One sortie equals one plane flying one mission. A ten-plane raid resulted in ten sorties. This became a delusional world. A sortie counted in the total even if our bombers were forced to dump their payloads short of the target, which often happened when MiGs appeared.

Is Trump the first president to give an adversary (Iran) a safe space? No:

At the end of March, in a speech declaring that he would not run for reelection in November, Lyndon Johnson changed the entire dynamic of the air war. He announced an immediate suspension of all bombing attacks north of the 20th parallel. Just like that, Rolling Thunder was over, neutralized by a lame-duck president. Up until then, the MiGs had been forced to operate from China, reducing their effectiveness. When LBJ told the world where we would not be bombing anymore, he essentially told the North Vietnamese we were giving their fighter regiments a safe space again. At the same time, the new restrictions greatly reduced the Air Force’s role in the air war over North Vietnam. The onus to continue it fell on the Navy.

I might print this out and tape it to the panel of the Cirrus SR20 to look at when I’m complaining about the lack of air conditioning:

Some time later, leading a strike mission at low altitude, Skank Remsen took a rifle round through the cockpit, straight through both thighs. He took his leg restraints, slid them up both legs, cinched them tight, and used them as tourniquets. He then flew one hundred and fifty miles and successfully landed aboard the carrier. Flight deck medical staff got him out of the airplane and rushed him to surgery. He refused medical evacuation to a stateside hospital and remained on board to heal. Two weeks later that tough old hombre was back in the saddle, flying combat missions with his boys. Now that’s my idea of real leadership.

Trigger warning: Nobody from Harvard or Columbia should read this book.

The Mediterranean, home of the U.S. Sixth Fleet, became a powder keg on October 6[, 1973]. That was the day our Israeli friends awoke to the greatest crisis of their lives: an imminent Arab invasion. The nation of Israel responded to that gathering storm with a massive preemptive strike. When the Yom Kippur War started, I was at Norfolk with the Dogs. All I could do was hope my Israeli friends, Eitan Ben Eliyahu and Dan Halutz and the rest of them, were out there knocking MiGs down and laying waste to ground targets.

The author eventually was promoted to command an aircraft carrier. The challenge of managing disgruntled and/or drug-addicted personnel turned out to be enormous. His Navy career ended when a sailor died and Michigan senators Carl Levin and Donald Riegle (both Democrats) faulted Pederson’s management of the ship.

A young airman named Paul Trerice collapsed and died while we were in Subic Bay about three weeks after we rescued the refugees. … The ship had just returned from a five-day visit to Hong Kong, where he was an unauthorized absentee. He was next in the CCU that April of 1981. My understanding from

Full post, including comments