Karen’s Mask Law Compliance Update (Boston to Minneapolis and back)

Here is one Karen’s report on the extent to which Americans are complying with the new mask laws. This is based on a May 30-June 3 trip from Boston to Minneapolis via Cirrus SR20 (“only a little slower, door-to-door, than a Honda Accord”). Stops included the following:

- Massachusetts

- Upstate New York (Syracuse, Niagara Falls)

- Michigan

- Wisconsin

- Minnesota

- Indiana

- Ohio

- Upstate New York (Elmira)

- Massachusetts

The first thing to note is that travel in the U.S. today is a lot like travel within Europe in the Middle Ages. Every state has its own rules and every city within a state may have additional rules. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, people are supposed to wear masks when walking on a deserted sidewalk or in an empty park. In other parts of Massachusetts, the rule is to wear a mask when in a store or in a crowded outdoor space. In Niagara Falls, the law requires a mask indoors, but not outdoors. In Minnesota, the state recommends that people wear masks in stores, but it is not required. In Minneapolis, Minnesota, on the other hand, masks are required indoors (except for Black Lives Matter protesters entering stores?).

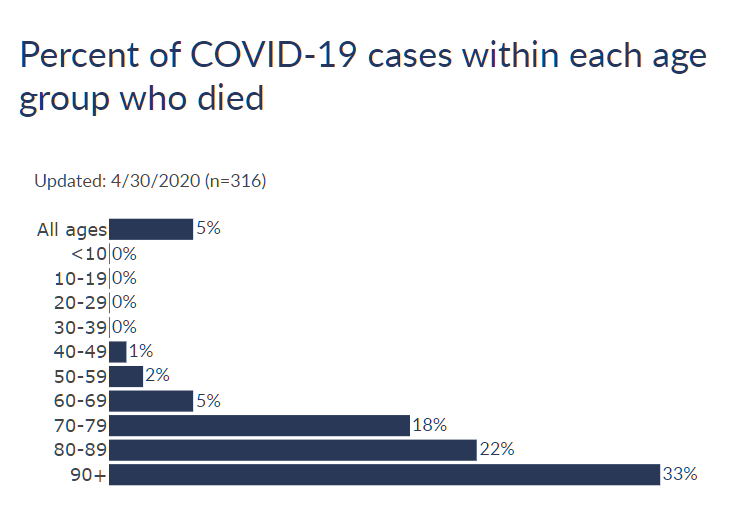

Our hotel in Niagara Falls, New York was typical. There was a sign on the door saying that everyone had to wear a mask in the lobby. Half the employees were wearing masks. Among the guests, compliance was 100 percent for Asians, 30 percent for whites, 10 percent for Hispanics, and 0 percent for African-Americans. In the adjacent state park, some of the employees had masks on, but almost none of the people walking around did (except at a few key viewpoints and when passing on bridges, people were at least 6′ apart most of the time).

FBOs had signs on the door saying that masks were required. Employees were hanging out inside unmasked, however. The arrival of a NetJets Phenom 300 was always a great occasion for mask display among both crew and passengers. The FBO in Michigan told us that the governor, Gretchen Whitmer, had recently come through. She’s a passionate advocate for lockdown and masks, but came off her private aircraft unmasked and, without any TV cameras around, came through the narrow FBO building unmasked.

Wisconsin? The state offers the same guidance as the W.H.O. (formerly “experts” but no longer worthy of the title due to their anti-mask heresy): don’t wear a mask unless you know what you’re doing and are washing your hands all the time (“Do not touch your mask while wearing it; if you do, clean your hands with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand rub. Replace the mask with a new one as soon as it is damp.”) No sign at the door of the FBO. Nobody wearing a mask inside or outside.

Eden Prairie, Minnesota: some signs recommending masks, but mostly official state advice signs to stay away if you have flu-like symptoms. Inside the Target, the employees were masked, but only about 40 percent of the customers. Mask use was low for the older shoppers. Ethnicity was a good predictor, as in New York: Asians were 100 percent masked. Muslim women who were otherwise covered from head to toe? 0 percent masked. Restaurants are open for outdoor dining; we enjoyed a meal under a tent and our young waitress had a mask… just underneath her nose.

Indiana: No masks at the FBO.

Ohio: Retail and restaurant workers were masked. Restaurants are open for dine-in, so we took advantage and had lunch at Tony Packo’s of M*A*S*H fame.

Upstate New York: No masks at any of the three FBO stops.

Return to Massachusetts: No masks at the FBO that had been an exemplary masked environment not even a week earlier. “Did you give up on masks?” I asked the guy behind the front desk. “There is a crowd of 20,000 protesting in downtown Boston right now. What’s the point?”

On walks around our neighborhood, which adopted a “You must have a mask around your neck at the ready whenever you’re out in public” rule, compliance with the law had fallen from 80 percent (a month ago, when the rule was new) to 20 percent.

Conclusion: Americans are capable of following an inconvenient rule for about a month.

Gratuitous Photos from Karen’s iPhone…

Niagara:

The right way to run shops in a plague environment:

Someone went a little nuts with the nose art for a Diamond Star DA-40:

One hand on the yoke and one hand on the life raft while crossing the 50-degree waters of Huron and Michigan:

“Nice Beaver” (Flying Cloud, KFCM, Minnesota):

I had planned to stay in downtown Minneapolis and walk around, but the civil unrest made it seem wiser to hole up in Eden Prairie. After two nights locked into the Hampton Inn, with only the occasional trip to a nearby strip mall for exercise and necessities, I had no difficulty understanding how people who’d been locked down for three months might riot. Midwestern cuisine:

Good news: outdoor dining is open. Bad news: Applebee’s is open.

Even at an FBO owned and run by African-Americans, Fox News prevails. Also, a shocking site for someone from Boston: an open gym!

Chick-fil-A and Hobby Lobby across the street from each other in suburban Toledo, Ohio. (The driver in front of us paid for our breakfast.)

Down by the river:

Preflight on the new propeller for the Cirrus:

At he National Museum of the Great Lakes, opening June 10:

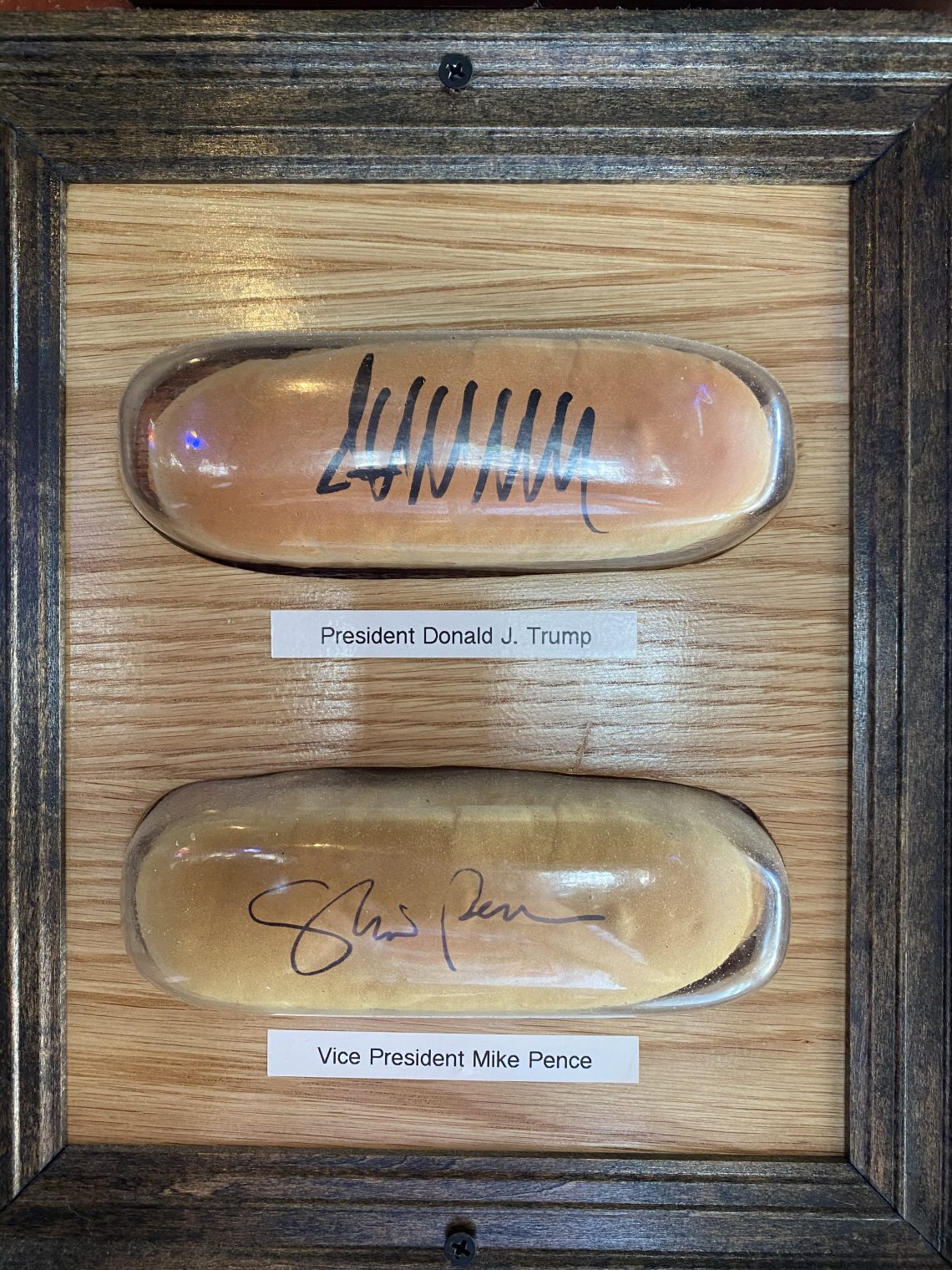

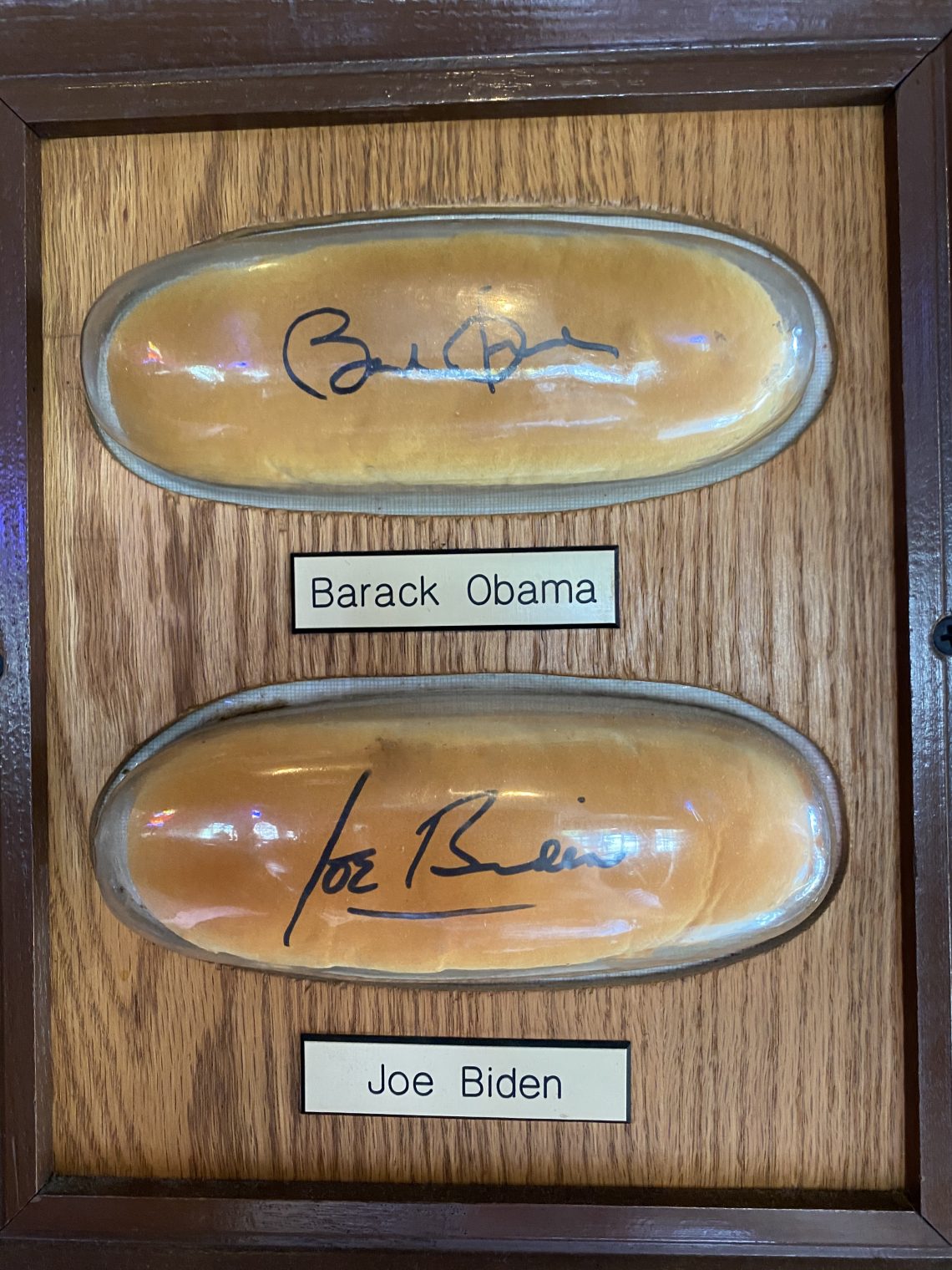

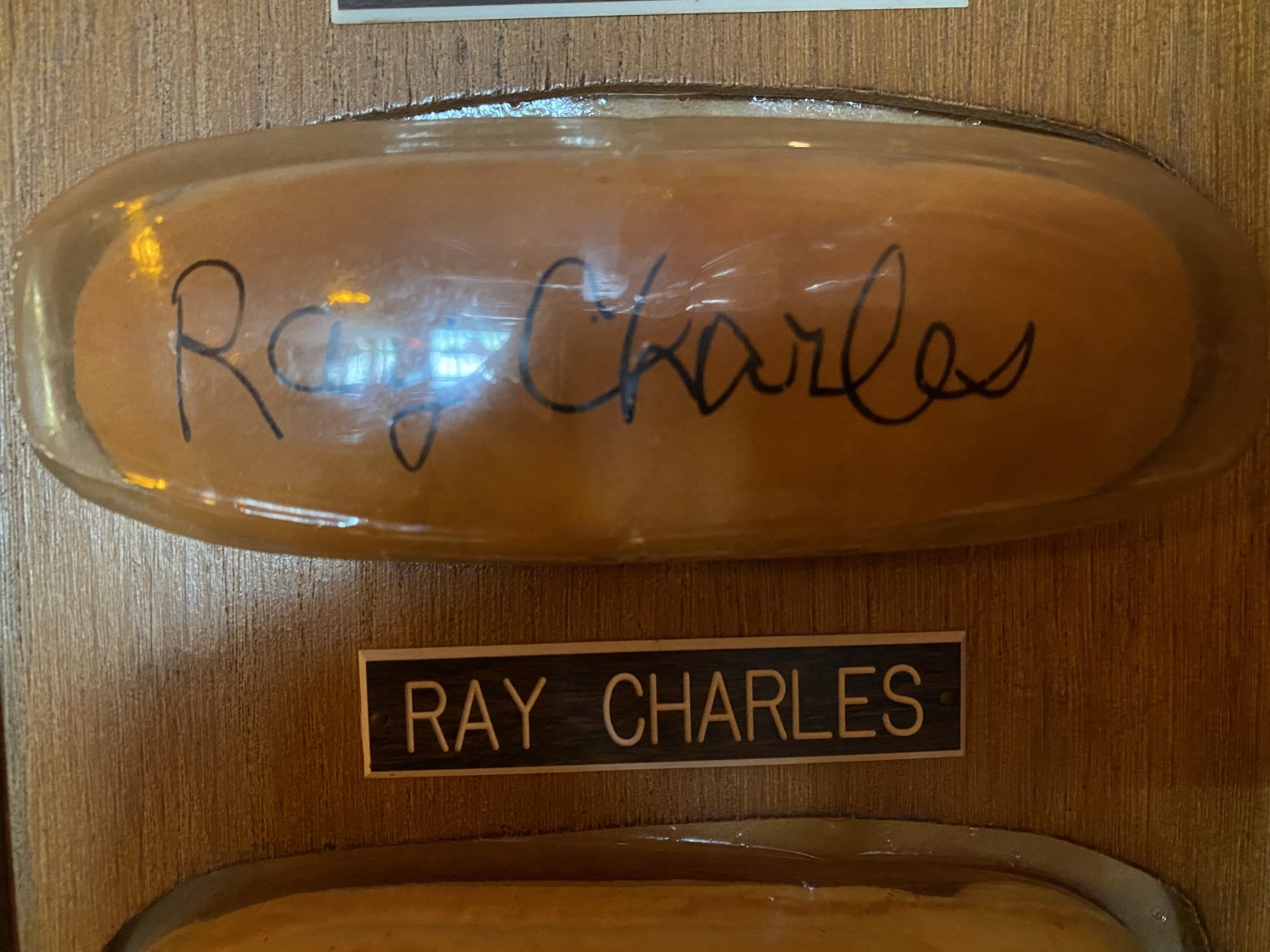

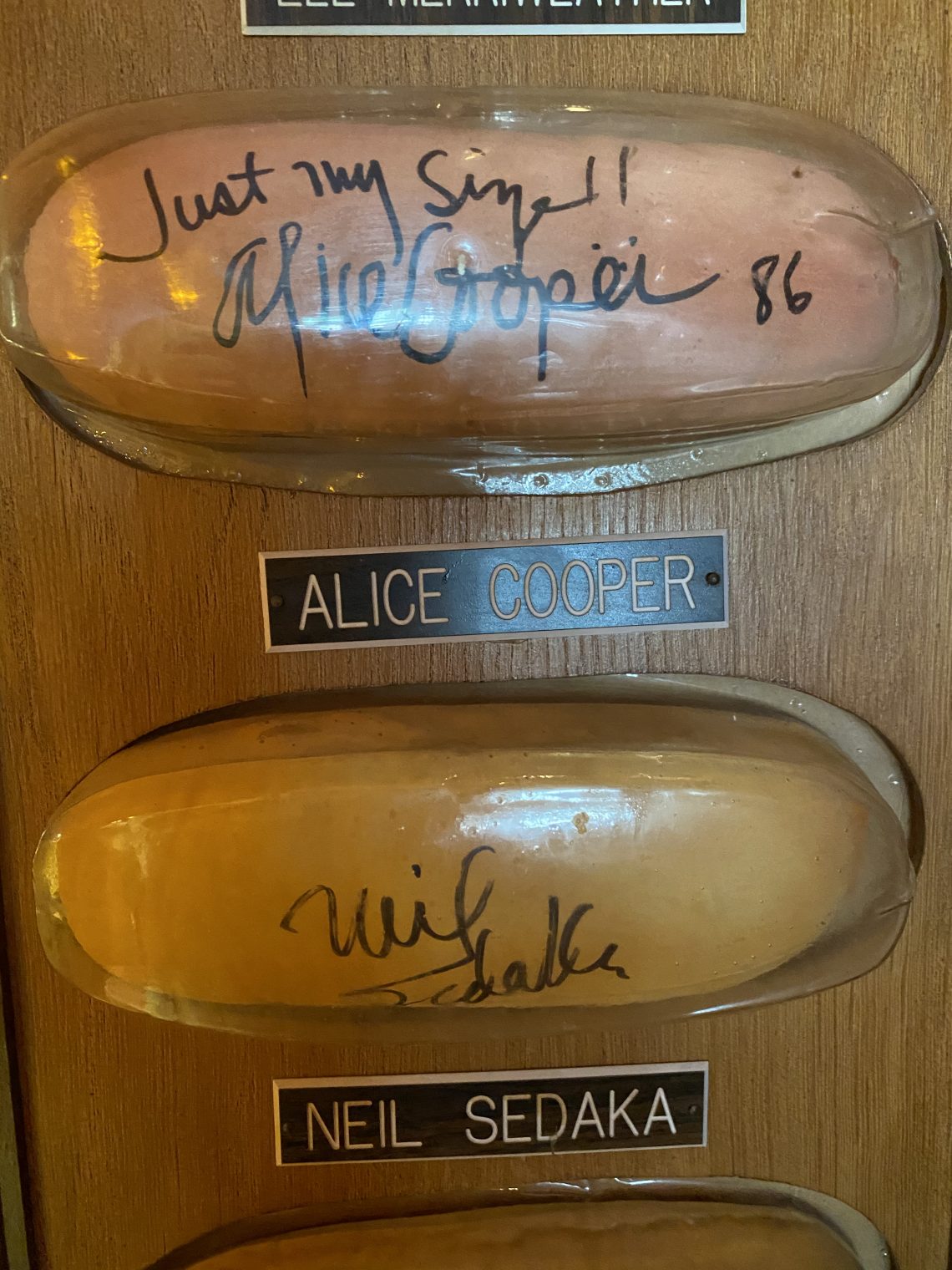

Trip highlight: Hungarian(?) food amidst signed plastic foam hot dog buns. Where else can Alice Cooper and Neil Sedaka be next to each other? Or Nancy Reagan and Jimmy Carter? For the younger readers: Sam Kinison on British TV. (here’s where he asked an inconvenient question about an earlier plague)

Approaching beautiful Cleveland with the super-wide lens:

Full moon at 7,500′:

Full post, including comments