Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City, by Greg Grandin, has some interesting facts about Henry Ford that I want to jot down.

Ford was 50 years old when he put together the Model T with the assembly line and began his ascent into legend:

SUCCESS CAME LATE to Ford. Born on a Michigan farm in 1863, he was forty years old when he founded the Ford Motor Company in Detroit, forty-five when he introduced the Model T, and fifty when he put assembly line production into place and began to pay workers a wage high enough to let them buy the product they themselves made. So while he came of age during the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, the America he lived in for the first half of his life was still mostly rural, and the changes he helped set in motion came stunningly fast. Ford didn’t invent the assembly line. He claimed he got the idea of having workers remain at one location and perform a single task from the “disassembly lines” found in Chicago’s and Cincinnati’s slaughterhouses, where butchers hacked off parts as pig and cow carcasses passed in front of them on conveyor hooks. Nor did he conceive the other central idea of modern mass production, that is, making parts as identical as possible to one another so that they would be interchangeable. But Ford did fuse these two ideas together as never before, perfecting the idea of a factory as a complex system of ever more integrated subassembly processes. Most of this innovation took place in Ford’s new Highland Park plant, opened in 1910 and designed by the architect Albert Kahn, who prior to his work with Ford had been associated with the anti–mass production arts and crafts movement.

Ford gave a tremendous amount of work to Kahn, a member of the Jewish tribe that Ford would come to blame for many of the world’s problems. If he didn’t mind Jewish workers, he did object to unionized workers, referring to unions as “the worst thing that ever struck the earth.”

It is difficult to conceive of how much vertical integration Ford achieved in the 1920s:

Ford moved forward with the construction of a new factory complex, which he built along the Rouge River, in the county of Dearborn, near where he was born. When it was finished, the River Rouge would be the largest, most synchronized industrial plant in the world: sixteen million square feet of floor space, ninety-three buildings, close to a hundred thousand workers, a dredged deepwater port, and the world’s largest steel foundry. Ford barges, trucks, and freight trains brought silica and limestone, coal and iron ore, wood and coal, brass, bronze, copper, and aluminum from Ford forests and mines in Michigan, Kentucky, and West Virginia to the Rouge’s gates and piers, and everything was organized to achieve maximum efficiency in receiving the material and getting it to the complex’s power plants, blast ovens, furnaces, mills, rollers, forges, saws, and presses, to be transformed into electricity, steel, glass, cement, and lumber.

Is it an original idea that we Americans with our superior technology and ideas can improve countries south of the border so much that nobody will want to migrate up here and begin living in means-tested public housing, subscribing to Medicaid, and shopping for food via EBT?

It was technology, production, and commerce that made history, and it would be not gunboats or marines that would tame the world but his car. “In Mexico villages fight one another,” Ford said, but “if we could give every man in those villages an automobile, let him travel from his home town to the other town, and permit him to find out that his neighbors at heart were his friends, rather than his enemies, Mexico would be pacified for all time.”

Compare to “The imperative to address the root causes of migration from Central America” (Brookings, 2021), “VP Harris To Work With Central American Countries To Address Root Causes Of Migration” (NPR, 2021), and “How to address the causes of the migration crisis, according to experts” (Vox, 2019).

Ford had a grand idea for upgrading life in one of the most benighted parts of the U.S.:

… Ford made a bid to realize his industrial pastoralism on a large scale in a depressed river valley—not in the Amazon but in Muscle Shoals, along a stretch of the Tennessee River in northwestern Alabama.

He also said he planned to establish a seventy-five-mile-long city, as thin as Manhattan but five and a half times its length. Other chaotic, unplanned cities grew in sprawls, in a “great circle” that trapped residents, never giving them a chance to “get a smell of the country air or see a green leaf.” Those who lived in Ford’s river metropolis, in contrast, would never be more than a mile from rolling hills and farmlands.

Frank Lloyd Wright remarked that Ford’s valley city, imagined above in an illustration published in Scientific American in 1922, was “one of the best things” he had ever heard of. Ford was “going to split up the big factory,” Wright said. “He was going to give every man a few acres of ground for his own.”

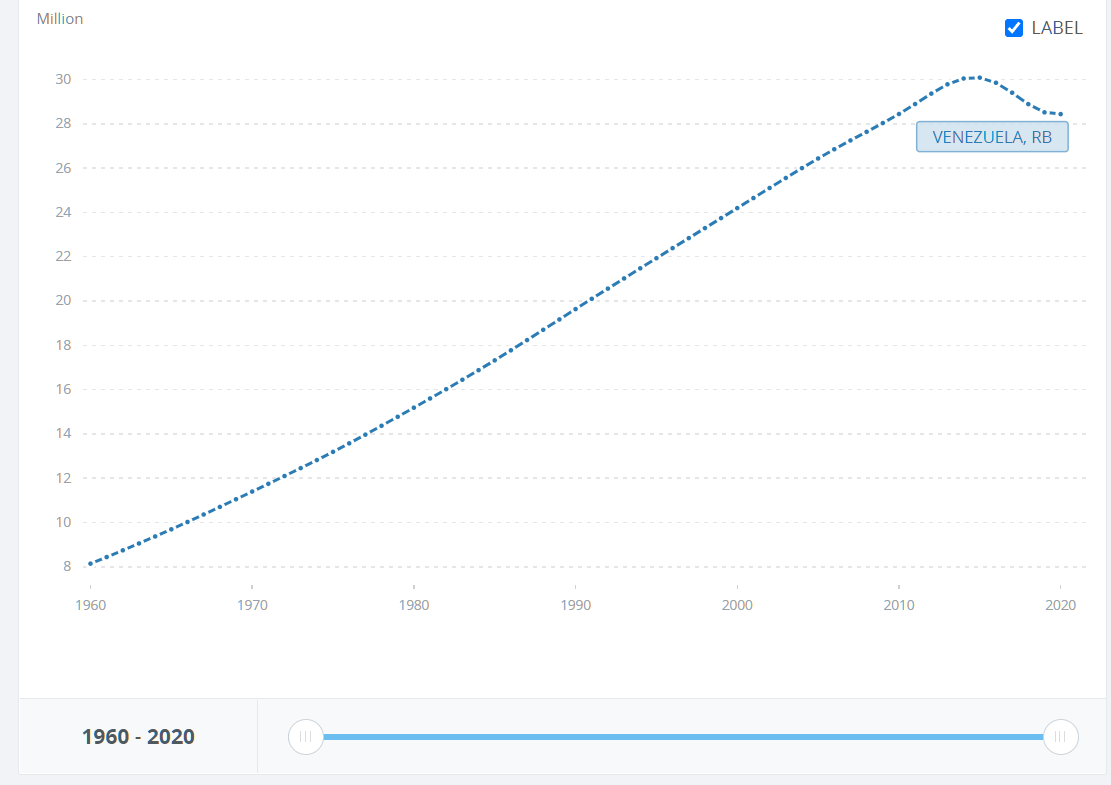

(Instead, of course, the U.S. became more urbanized as the population grew from 106 million (1920) to 330 million (today) and a median-earning worker cannot afford an apartment, much less “a few acres of ground” anywhere near a job.).

Extreme climate events are new?

A week earlier [in 1928], he and Edsel had taken the Ormoc out on a trial run down the Rouge River into Lake Erie. But now, a heat wave had settled over lower Michigan, killing scores of people. Defying the Amazon’s dry season from a world away was one thing. Suffering Detroit’s humidity in the flesh was another, so Ford escaped the city by taking off on one of his road trips.

Ford was an early enthusiast for aviation, having first flown in 1927 (including some stick time), according to the author (the Henry Ford Museum page on aviation shows that he began working to build airplanes, however, in 1924 (giving up in 1933)).

Aviation pioneers failed to predict the military uses of aircraft:

The disappointment of Alberto Santos-Dumont’s life was not that he didn’t get credit for inventing flight, though he did resent that the Wright brothers won all the acclaim. His real heartbreak was that he lived long enough to see the machine he helped develop be used as an instrument of death. Santos-Dumont wasn’t an ideological pacifist like Henry Ford, but he did hope that airplanes would knit humanity closer together in a new peaceful community, just as Ford had believed that his car, along with other modern machinery, could bring about a warless world and a global “parliament of man.” Both were of course proven wrong by World War I, which broke the conceit of many like Ford and Santos-Dumont that technology alone would usher in a new, higher stage of civilization. “I use a knife to slice gruyere,” Santos-Dumont said when war broke out in Europe, “but it can also be used to stab someone. I was a fool to be thinking only of the cheese.”

Ford dealt erratically with the fact that, after all his high-handed opposition to World War I, he turned his factories over to war production. He continued to speak out provocatively against war, maintaining his position that soldiers were murderers and quoting Tennyson’s “Locksley Hall” to the end of his days. Yet Ford’s faith in America as a revitalizing force in the world led him to say that he would support another war to do away with militarism. “I want the United States to clean it all up,” he said. No wonder the Topeka Daily Capital said that Ford put the “fist in pacifist.”

Orville Wright, for his part, predicted after World War I that the airplane had made war so terrible that no country would start a future war. The author reminds us of the 1932 war between Bolivia and Paraguay over non-existent oil that killed nearly 200,000 people. Airplanes were used on both sides.

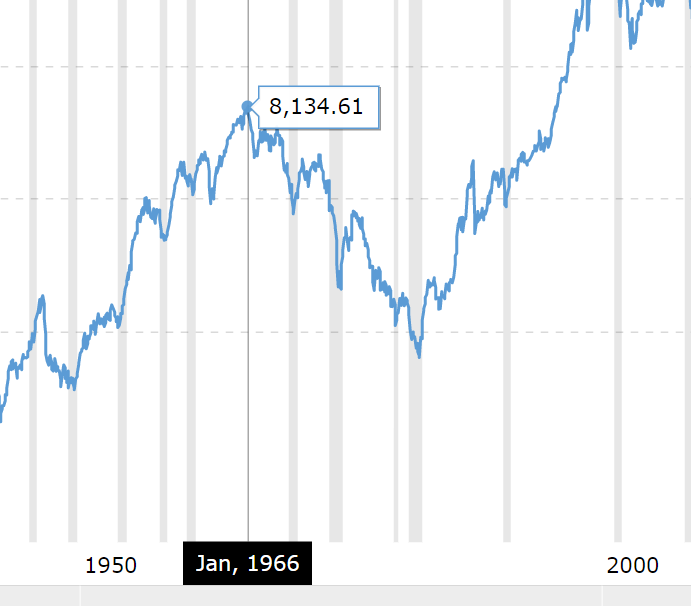

Even the smartest best-connected people failed to predict that the Great Depression would last far longer than any previous economic downturn.

Ford at first restrained himself from using the crash to scold Wall Street and lash out at the money interests. He instead responded in a way many deemed responsible, preaching his gospel of consumer spending as a way out of the downturn. To back it up, he pledged that not only would he continue production at the Rouge full bore but he would raise his daily minimum wage from $6 to $7 a day. Ford seemed well positioned to lead the recovery: he himself had little invested in stocks, so his personal fortune was untouched, and his company, unlike General Motors, whose share price plummeted, wasn’t publicly traded. Yet demand for the new Model A gradually slowed, and inventories backed up. Ford lowered its price, taking the difference out of dealers’ commissions. But by the end of 1930, there was no margin left for any more reductions. The company quietly began to cut production and to buy more and more parts from outside low-wage suppliers—thus beginning the erosion of the fearsome self-sufficiency of the Ford Motor Company. By early 1931, the company had slashed the number of weekly hours of most workers, rendering meaningless Ford’s vaunted Seven Dollar Day. Later that year, the company officially reduced that as well. And then in August the assembly line ground to a halt—Ford had more cars than customers to buy them. Just four years after its introduction in late 1927, the Model A, which Ford had hoped would have as long a run as the T, was history.

The author reminds us that the solution to any economic problem is bigger government!

Of course, his exhortations to self-reliance and patronage of village industries had as little chance of solving the problems revealed by the Great Depression as Fordlandia managers had of taming the Amazon. Yet Ford never relented in his condemnation of the New Deal’s solution to the crisis: the promotion of unionism, government regulation of industry, and establishment of federal relief. Specifically, Ford refused to warm to Roosevelt and his New Dealers.

(See The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression, by a WSJ reporter, for the opposite perspective! Amity Shlaes says that FDR and bigger government are precisely what dragged out the Great Depression until World War II.)

How new is the idea of using distilleries to make hand sanitizer and/or making fuel in a way that is carbon-neutral?

[in the 1930s] Ford lobbied for Prohibition, saying that Detroit’s distilleries could be converted to make biofuels.

How new is the inability of a typical American worker to afford the kind of housing that he/she/ze/they thinks he/she/ze/they is entitled to?

Then he turned to Fordlandia’s housing crisis. The plantation’s original plans from 1928 called for the building of four hundred two-room houses “per Ford Motor Co. drawings,” at a cost of $1,500 each—clearly insufficient for the thousands of workers and their families who had come to the settlement. In truth, this failure to address workers’ housing needs was not that different from what was happening in Michigan. Despite his famed paternalism and acquisition of towns like Pequaming, Ford, except for a small experimental community of 250 homes, largely tried to avoid providing houses for his Dearborn and Detroit workers, believing his high wages would be enough to create prosperous neighborhoods. He steadfastly ignored the city’s mounting housing problems, which had dogged the automobile industry since the beginning of its expansion. Workers lived in overcrowded slums, flophouses, and tenements, most without decent plumbing, electricity, or heat, with African Americans consigned to the worst of the lot.

With a touch more focus on those who identified as “women” or

Full post, including comments