Florida comes up with a scheme for increasing taxes on private workers via a property tax exemption for government workers

On the ballot this year… “Florida Amendment 3, the Additional Homestead Property Tax Exemption for Certain Public Service Workers”:

A “yes” supports authorizing the Florida State Legislature to provide an additional homestead property tax exemption on $50,000 of assessed value on property owned by certain public service workers including teachers, law enforcement officers, emergency medical personnel, active duty members of the military and Florida National Guard, and child welfare service employees.

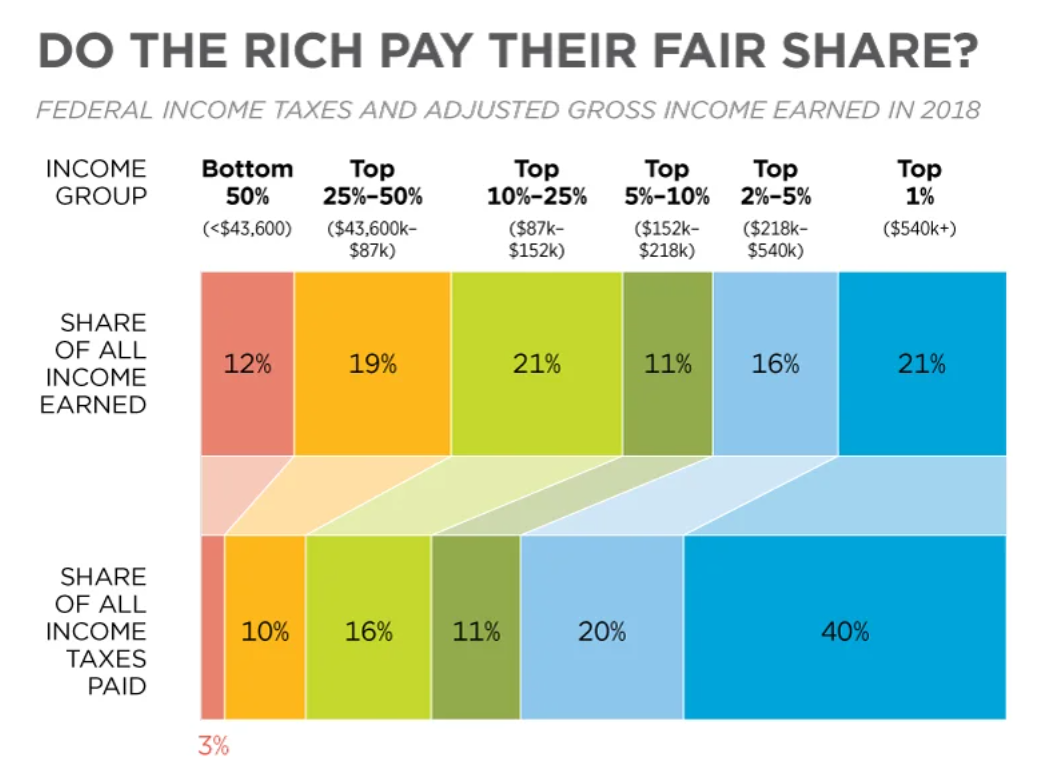

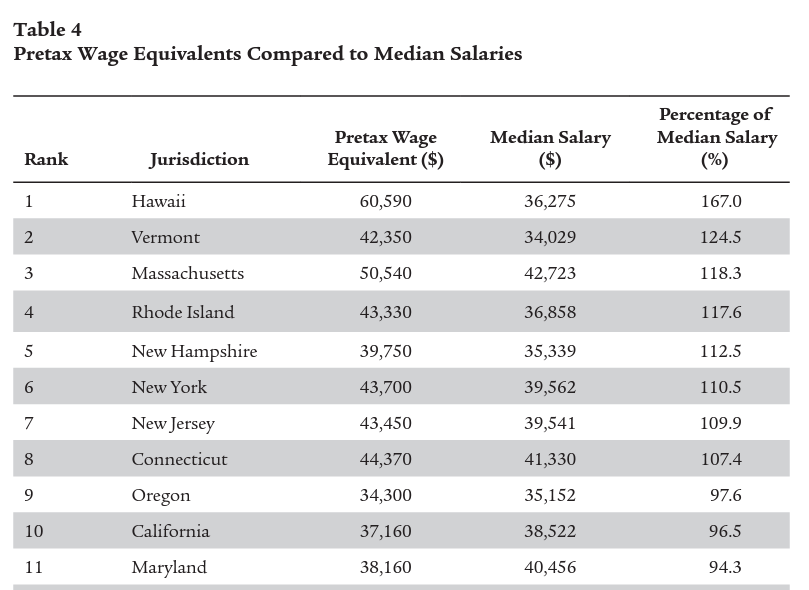

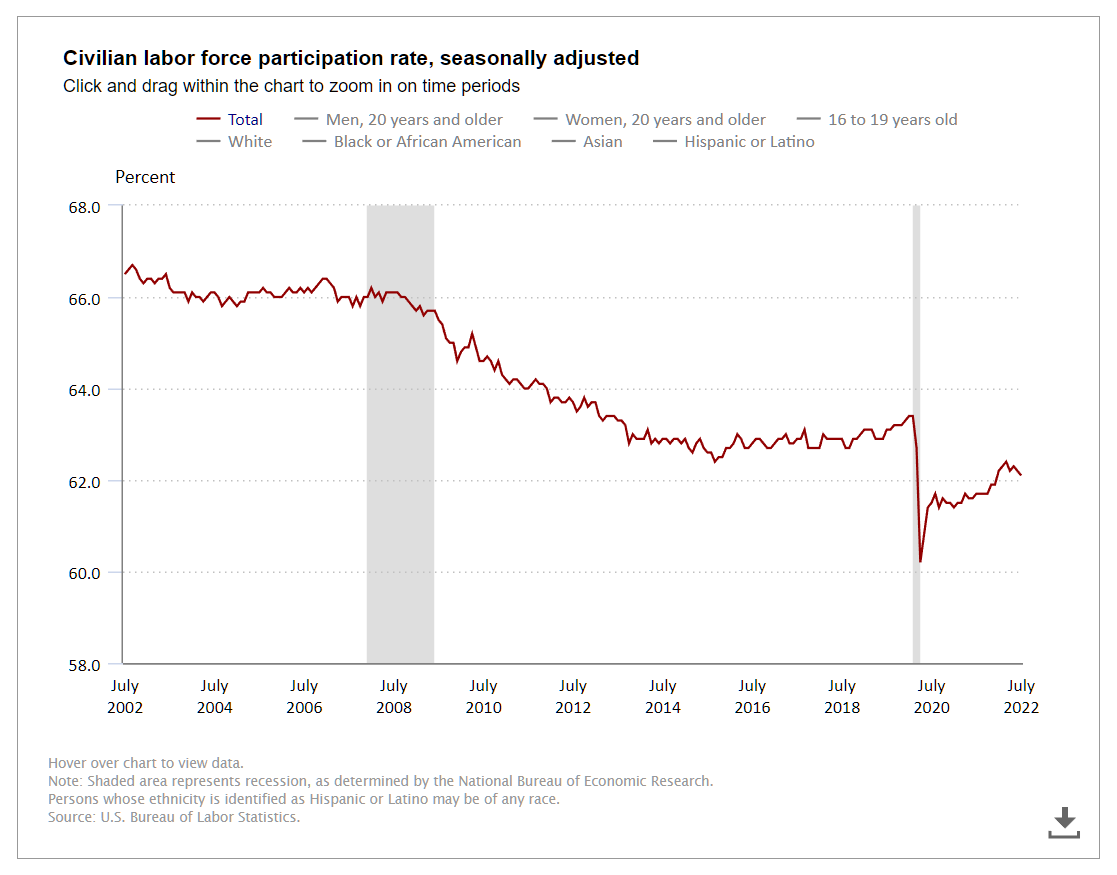

I wonder if this will catch on nationwide as a stealth way to increase the amount of money that flows from those who aren’t part of the government to those who are. Instead of increasing property tax rates and then giving government workers a raise, which would be readily noticed, the scheme gives government workers a boost in spending power by relieving them of paying property taxes (to at least some extent). Note that this only helps government workers who are rich enough to own houses. Landlords who rent to government workers won’t get a property tax reduction so government workers who rent, like our local friend who is a police officer for a city down the coast, won’t get a rent reduction.

This could be expanded so that when government workers purchase items at retail they don’t have to pay sales tax (there is typically already a mechanism for sales tax exemption for resale, non-profit orgs, etc.).

Separately, the local police officer renter is an interesting example of someone who benefits from open borders. Without all of the crime committed in a Haitian immigrant neighborhood, the seaside city where she works wouldn’t have needed or wanted to hire additional police officers.

Full post, including comments