Continuing my posts about Lionel Shriver’s The Mandibles: A Family, 2029-2047…

The novel directly concerns four generations within one family and the relationships among these generations as well as the way in which a society’s GDP is parceled out to various age groups.

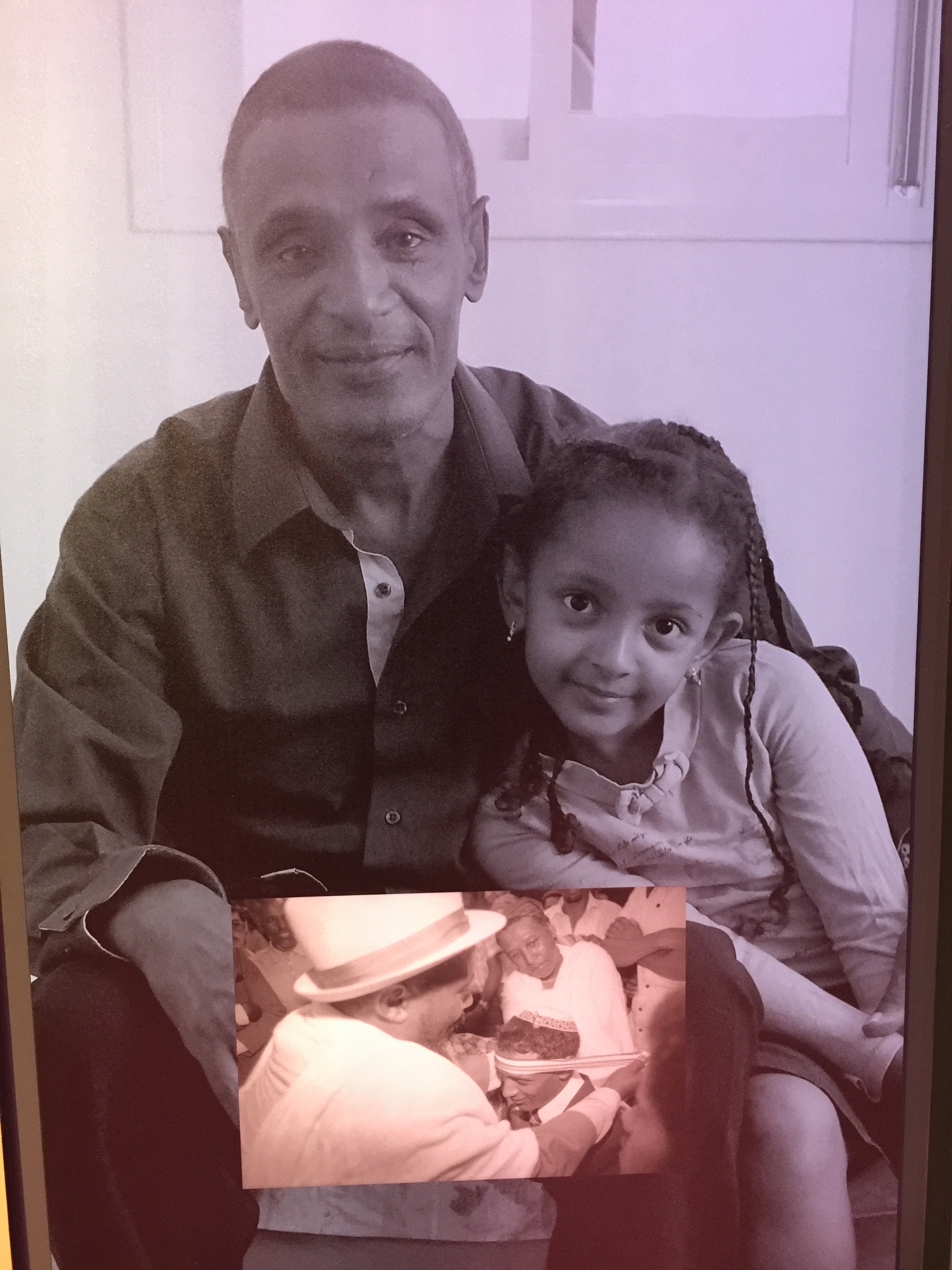

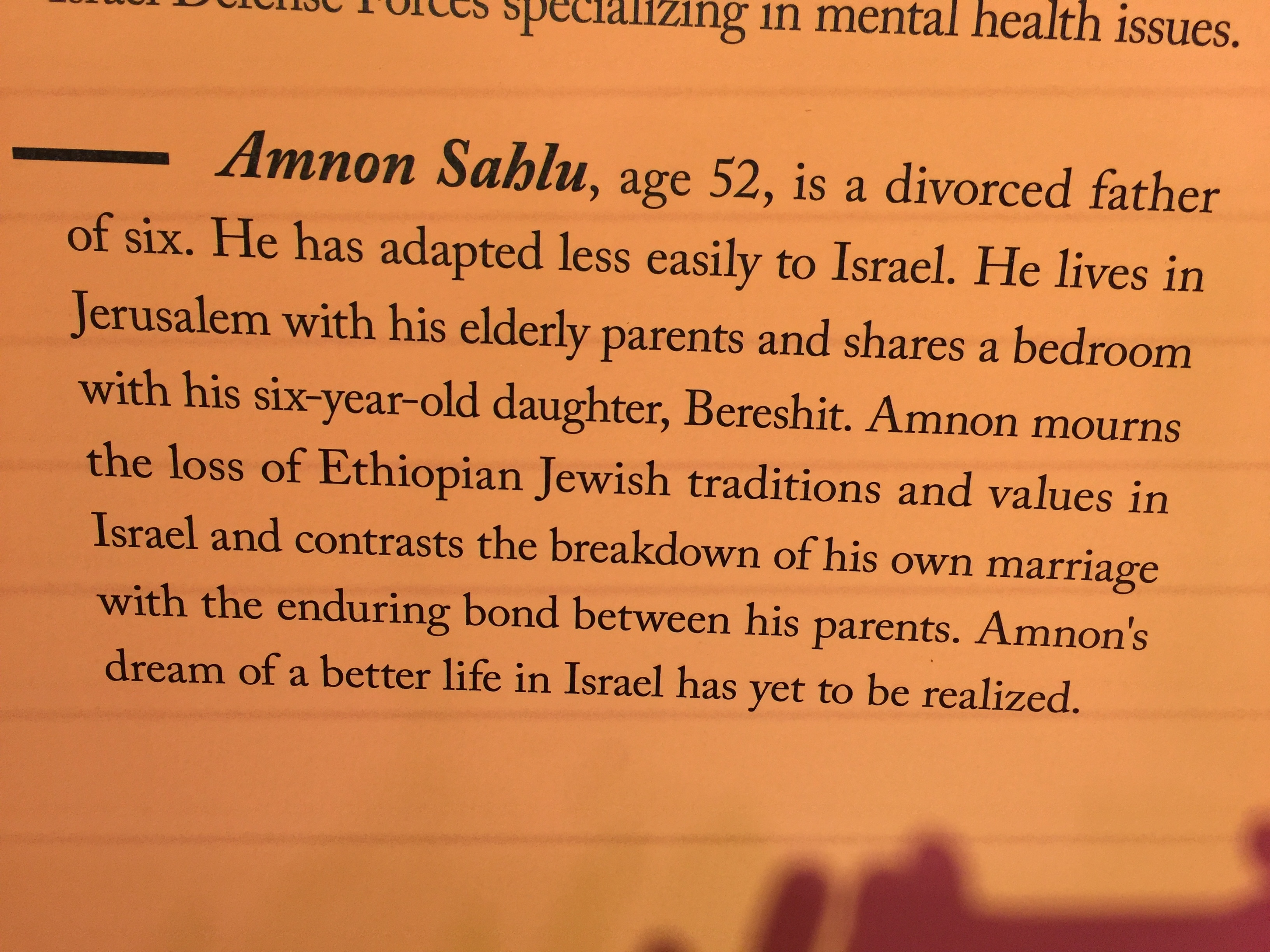

For those periods in the novel when the U.S. GDP is flat or shrinking, the younger generations resent the money being spent on the old. Being old is psychologically tough, even at the beginning of the novel before the meltdown:

I see the same thing in my elderly clients all the time. They have different obsessions, of course: we’re about to run out of water, or run out of food, or run out of energy. The economy’s on the brink of disaster and their 401(k)s will turn into pumpkins. But in truth they’re afraid of dying. And because when you die, the world dies, too, at least for you, they assume the world will die for everybody. It’s a failure of imagination, in a way—an inability to conceive of the universe without you in it. That’s why old people get apocalyptic: they’re facing apocalypse, and that part, the private apocalypse, is real. So the closer their personal oblivion gets, the more certain geriatrics project impending doom on their surroundings

Inter-generational conflict is worse when the younger generation is a different ethnic group than the older generation:

[a young man who works for a senior citizens’ outdoor excursion company called “Over the Hill”] … Because they don’t like following a guide. Especially a Lat guide. They’re enraged that Lats are running the show now, since somebody has to—” “Enough.” Florence threw the cabbage into what was starting to look like pork soup. “You forget. I’m on your side.” “I know you get sick of it, but you’ve no idea the waves of resentment I get from these crusties every day. They want their domination back, even if they think of themselves as progressives. They still want credit for being tolerant, without taking the rap for the fact that you only ‘tolerate’ what you can’t stand. Besides, we gotta tolerate honks same as they gotta put up with us. It’s our country every bit as much as these has-been gringos’. It’d be even more our country if these tottering white cretins would hurry up and die already.”

In an economy where it is tough to earn money via work, young people may pay attention to and spend time with old people to ensure an inheritance:

It was also standard on the two-hour trip from Brooklyn—this leafy section through Connecticut was pleasant—for Carter to question his motivations for these visits. With an eye to the long view, you naturally dote on an elderly parent as a subtly selfish prophylactic: to be able to assure yourself, on receipt of that fatal phone call, that you’d been devoted. Sometimes being a shade more attentive than you’re quite in the mood for can prevent self-excoriation down the line. After all, old people have a horrible habit of kicking it right after you ducked seeing them at the last minute with an excuse that sounded fishy, or on the heels of a regrettable encounter in which you let slip an acrid aside. To be dutiful without fail is like taking out emotional insurance. Yet in Carter’s case, the self-interest was crassly pecuniary. Did he keep in his father’s good graces with monthly runs to the Wellcome Arms only to safeguard his inheritance from, say, a rash or spiteful late-life impulse to endow a chair at Yale? He’d never know. Worse, his father would never know, and might not ever feel confidently cherished for himself. A family fortune introduced an element of corruption.

Old people drive the economy and people are anxious to get into the driver’s seat:

But as things stood at present: after a dip in the thirties, life expectancy had better than recovered. On average, Americans were living to ninety-two. The US sported an unprecedentedly large cohort of senior citizens. In contrast to Willing’s passive generation, typified by low rates of electoral participation, nearly all the shrivs voted, making it political anathema to restrict entitlements. Together, Medicare and Social Security consumed 80 percent of the federal budget.

From the start, he knew the variety of employment widely available: home health aide placements, health insurance and billing, design and maintenance of healthcare websites, answering healthcare help lines, medical device manufacture, service of medical devices, medical transport, medical research, pharmaceutical manufacture, pharmaceutical research, pharmaceutical advertising, hospital laundry, hospital catering, hospital administration, hospital construction, and work in assisted-living establishments that served every level of decrepitude from mildly impaired to moribund.

“So what’s up with your parents?” Willing interceded. “Dad’s two years from sixty-eight,” Goog said. “Then he’ll be sitting pretty.” People used to dread being put out to pasture. Desperate to qualify for entitlements, these days everyone couldn’t wait to be old.

The simplest way to get old is to sleep:

Willing was also perplexed by why slumbering hadn’t taken off decades earlier. When recreational drugs were legalized, regulated, and taxed, they became drear overnight. Only then did people get wise to the fact that the ultimate narcotic had been eternally available to everyone, for free: sleep. A pharmaceutical nudge into an indefinite coma was cheap, and a light steady dose allowed for repeated dream cycles. Inert bodies expend negligible energy, so the drips for nutrition and hydration had seldom to be replenished (slumbers were hooked to enormous drums of the stuff). The regular turning to prevent pressure sores provided welcome employment for the low skilled. Slumbers didn’t require apartments—much less maXfleXes or new clothes. They needed only a change of pajamas and a mattress. An outmoded designation revived, “rest homes” denoted warehouses of the somnambulant, who were only roused and kicked out once their prepayments were extinguished. Previous generations had scrounged to buy property. Many of Willing’s peers were similarly obsessed with scraping together a nest egg, but with an eye to dozing away as many years of their lives as the savings could buy.

The eeriest part of the book is that it anticipates the Sagamihara stabbings. In a society with a lot of dependents, Shriver predicts that workers whose mental health declines may target those dependents.

More: Read The Mandibles.

Full post, including comments