One thing that I’ve learned from going to public lectures on astrophysics or planetary exploratoration is that people with no sci/tech education love science and hate engineering. The more irrelevant the topic to everyday life, the more fascinating. At a (fascinating) lecture by Brian Keating, author of Losing the Nobel Prize, I remarked to a friend “Look how excited people are to hear about stuff that they can’t do anything about, that happened billions of years ago, and that won’t have any effect within their lifetimes. Even if you offered to pay, however, I bet that none of these people would be willing to sit through a lecture on how their televisions or personal computers or smartphones work.”

The Perfectionists: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World, by Simon Winchester (author of the truly awesome Krakatoa: The Day the World Exploded: August 27, 1883) fights against humanity’s indifference to engineering and engineers. I would love to hear from non-engineer readers who’ve read this book.

The ancients were not always successful:

Modern investigators have concluded that the device was very well made, “with some parts constructed to accuracies of a few tenths of a millimeter.” By that measure alone, it would seem that the Antikythera mechanism can lay claim to being a most precise instrument—and, crucially for this introduction to the story, maybe the first precision instrument ever made. Except that there is an inherent flaw in this claim. The device, as model-tested by the legions of fascinated modern analysts, turns out to be woefully, shamefully, uselessly inaccurate. One of the pointers, which supposedly indicates the position of Mars, is on many occasions thirty-eight degrees out of true.

The early steam engine guys were partying like Kavanaughs:

What is especially and additionally noteworthy, though, is that a historic convergence [with James Watt] was in the making. For, living and working nearby in the Midlands, and soon to produce a patent himself (the already noted Number 1063 of January 1774, an exact one hundred fifty patents and exactly five years later than James Watt’s), was no less an inventor than John Wilkinson, ironmaster. By then, Wilkinson’s amiable madness was making itself felt throughout the ferrous community: all came to learn that he had made an iron pulpit from which he lectured, an iron boat he floated on various rivers, an iron desk, and an iron coffin in which he would occasionally lie and make his frightening mischief. (Women were in plentiful attendance, despite his being a somewhat unattractive man with a massively pockmarked face. He had a vigorous sex drive, fathering a child at seventy-eight by way of a maidservant, a calling of which he was inordinately fond. He kept a seraglio of three such women at one time, each one unaware of the others.)

Before working hard was outlawed, the French were the pioneers in automobiles and also in precision gun-making:

IT WAS IN the French capital in 1785 that the idea of producing interchangeable parts for guns was first properly realized, and the precision manufacturing processes that allowed for it were ordered to be first put into operation.

Henry Ford and Henry Royce, the engineer behind Rolls-Royce (Rolls was a sales guy), were both born in 1863. Royce’s aunt paid for the boy to serve as an apprentice for three years in a railroad workshop. Royce started with cranes and began making cars in 1903, partnering with Rolls in 1904. The authors shows how Henry Ford’s basic cars were equally dependent on high precision:

The Model T had fewer than one hundred different parts (a modern car has more than thirty thousand).

Within Rolls-Royce, it may seem as though the worship of the precise was entirely central to the making of these enormously comfortable, stylish, swift, and comprehensively memorable cars. In fact, it was far more crucial to the making of the less costly, less complex, less remembered machines that poured from the Ford plants around the world. And for a simple reason: the production lines required a limitless supply of parts that were exactly interchangeable.

There is a chapter on the modern jet engine. As with many other innovations in aviation, Americans were late to realize the value.

It was Frank Whittle, the first son of a Lancashire cotton factory worker turned tinkerer, who invented the jet engine.

Also, it is worth noting that American laboratories were curiously blind and deaf to the idea of a turbine-powered engine as having any utility for the aircraft industry, and the United States pursued almost no research until the 1940s. It was left to the diminutive Frank Whittle, therefore, to pursue the dream, fired by his famous criticism of the outmoded nature of propeller-driving piston engines, a condemnation that resonates today. “Reciprocating engines are exhausted,” he declared. “They have hundreds of parts jerking to and fro and they cannot be made more powerful without becoming too complicated.* The engine of the future must produce two thousand horsepower with one moving part: a spinning turbine and compressor.”

Jet engines are beasts of extreme complexity bound up within a design of extraordinary simplicity. All that ensures they work as well as they do are the rare and costly materials from which they are made, the protection of the integrity of the pieces machined from these materials, and the superfine tolerances of the manufacture of every part of which they are composed. Frank Whittle had to deal with these harsh realities for ten testing years, from the moment he had his grand idea in the summer of 1928. Every imaginable obstacle was put in his way during that decade. Nevertheless, he persisted.

(Based on that last sentence, is it same to assume that Frank Whittle identified as a woman?)

It is impressive how far into the future Whittle was able to see:

.. first planted the seed at the end of his stint as a flight cadet at Cranwell, the Royal Air Force academy in the English Midlands. Cadets at the time were each obliged to write a short scientific thesis on a topic that interested them, and Whittle’s paper has since become a part of aeronautical legend: with all the hubris of a young man on the make, he titled it “Future Developments in Aircraft Design.” At the time of his graduation from Cranwell, powered flight was only a quarter of a century old. The aircraft in which cadets such as Whittle trained were mostly biplanes—they had wooden frames, were in no sense streamlined, had no enhancements such as retractable undercarriages or pressurized cabins, flew at low altitudes, and trundled through the skies at speeds seldom exceeding 200 miles an hour. RAF fighters, in many ways more advanced than most, averaged a puny 150 miles per hour, and operated at only a few thousand feet above sea level.

It was fifteen months later, in October 1929, that the penny finally dropped. Whittle was by now a fully qualified general duties pilot, stationed in Cambridgeshire, and while training and teaching others to fly, he obsessively ruminated and calculated and imagined the kind of engine that could possibly make aircraft go lightning fast. All his designs involved some kind of supercharged piston engine. At the same time, he could see that even a modest increase in engine power, and thus aircraft speed, would require a very much larger and heavier engine—an engine probably much too big and heavy for any aircraft to carry. He was about to abandon the quest when, suddenly, one day that October, he had his brain wave: why not, he thought, employ a gas turbine as an engine, a gas turbine that, instead of driving a propeller at the engine’s front, would thrust out a powerful jet of air from the engine’s rear? An idea that would change the world in unimaginable ways had come to Frank Whittle when he was just twenty-two years old.

Moreover, a gas turbine could also, in theory, be vastly more powerful than a piston engine, and for a very simple reason. A crucial element in any combustion engine is air—air is drawn into the engine, mixed with fuel, and then burns or explodes. The thermal energy from that event is turned into kinetic energy, and the engine’s moving parts are thereby powered. But the amount of air sucked into a piston engine is limited by, among other factors, the size of the cylinders. In a gas turbine, there is almost no limit: a gigantic fan at the opening of such an engine can swallow vastly more air than can be taken into a piston engine—as a rule of thumb, seventy times as much, in the early, Whittle-era jets.

The guy who engineered our modern world of travel was not celebrated like a scientist with a Nobel Prize. You’re only as good/valued as your most recent project:

Frank Whittle, initially honored—King George VI conferred a knighthood—and somewhat revered, did not have as happy a time in postwar England as one might think he deserved. Power Jets was nationalized, and its chief engineer sidelined, put out to pasture. He traveled, he lectured, he wrote, and he particularly savored his election to a fellowship of the Royal Society. He won prizes, the most valuable of which, at around half a million dollars, he decided generously to split with Hans von Ohain, the German inventor whose Heinkel-powered plane had been the true first to fly with a turbojet engine. Whittle argued often for the good sense of building a supersonic passenger plane, and badgered officials long before Concorde was a drawing board dream. But no one listened, and by 1976, with his marriage failed, he decided to light out for America, and spent his final years in a suburb of Washington, DC.

The chapter includes a fascinating desciption of issues with cooling power turbine blades and how a small manufacturing error led to a dramatic uncontained engine failure for Qantas 32, an Airbus A380 that barely made it back to Singapore.

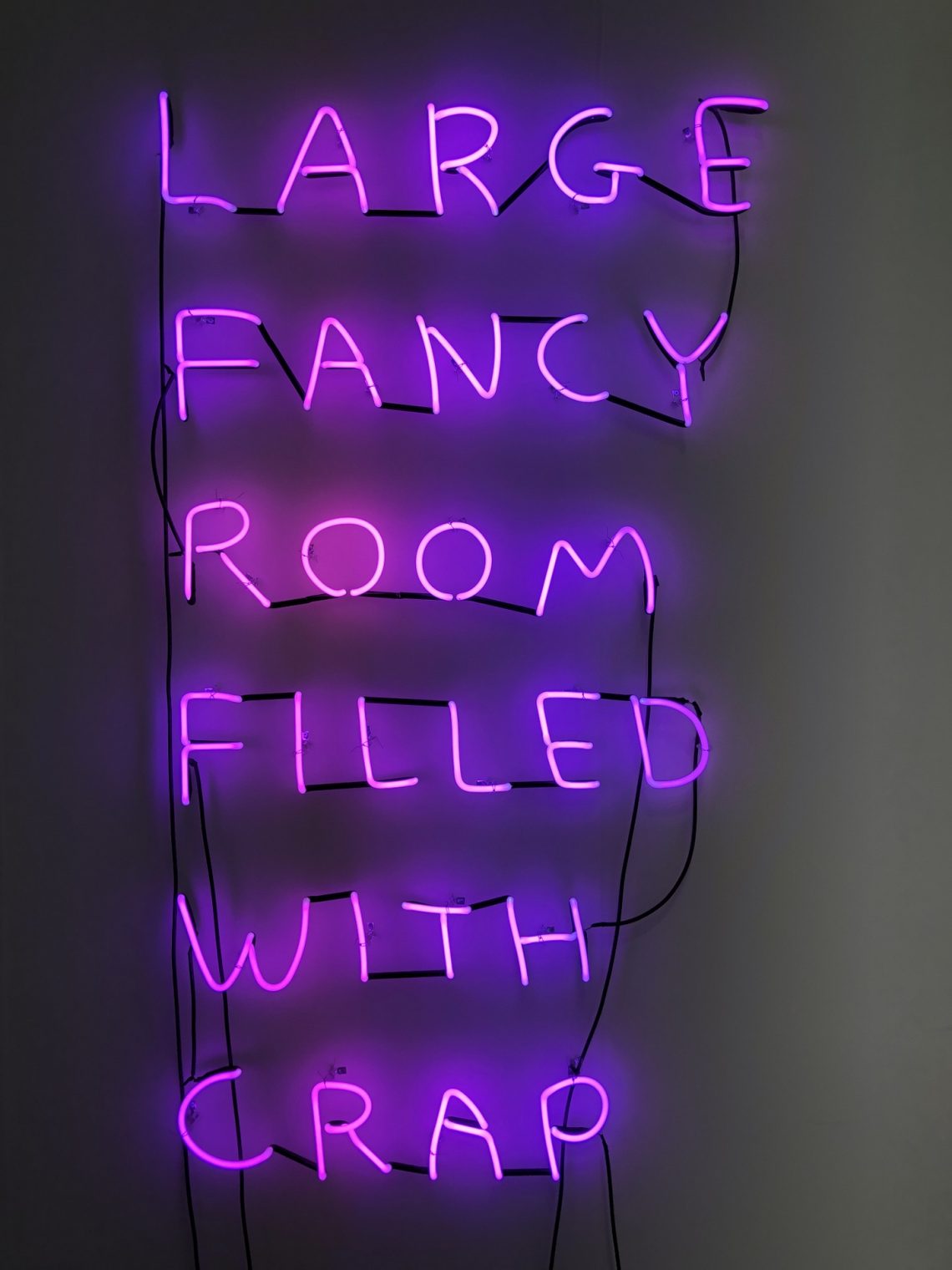

The book is a personal selection of topics, not a survey of the most important engineering developments or contributions. Each chapter stands on its own, so if you don’t want to relive the Hubble Space Telescope fiasco you can just skip that chapter. Some of the later chapters on newer technology were less interesting, perhaps because they lack the illustrations that would serve to explain how systems work.

The 74-year-old author is somewhat out of step with the times. Except by using pronouns, the book does not mention the gender IDs of any of the engineers featured. Nor is their skin color described. This book cannot be proudly displayed alongside Rosie Revere, Engineer or Women in Science: 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World.

More: Read The Perfectionists: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World

Full post, including comments