My inbox has been filling up lately with emails regarding purported hate crimes against Asian-Americans. Somewhat curiously, these emails are coming from institutions that explicitly discriminate against Asian-Americans (see “A Ceiling on Asian Student Enrollment at MIT and Harvard?”, for example, and Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard).

Harvard graduate Tom Lehrer wrote about this in his song “National Brotherhood Week“:

it’s Fun to eulogize the

People you despise

As long you don’t let them in your school.

From Larry Bacow, President of Harvard:

For the past year, Asians, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders have been blamed for the pandemic—slander born of xenophobia and ignorance. … Footage of individuals being targeted and assaulted has driven home a rise in aggression and violence across the nation. Today, we continue to reel in the wake of eight murders in Georgia—six of the victims of Asian descent—and to contend with events that shock the collective conscience.

(If only six of the victims were of Asian descent, what’s El Presidente’s theory for how this was an anti-Asian hate crime? The murderer hated Asians, but was not intelligent enough to distinguish between Asians and non-Asians?)

Harvard must stand as a bulwark against hatred and bigotry. We welcome and embrace individuals from every background because it makes us a better community, a stronger community.

I long for the day when I no longer have to send such messages. It is our collective responsibility to repair this imperfect world. To Asians, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders in our community: We stand together with you today and every day going forward.

(Is there, in fact, anyone who blames “Pacific Islanders” for COVID-19 or coronapanic? Readers: Have you heard someone curse Samoans, Fijians, or Tongans for causing the deaths of 82-year-olds in Maskachusetts?)

From Martha Tedeschi, director of the Harvard Art Museums, where the paychecks keep coming despite the museum being closed.

I am reaching out to the extended museum family of the Harvard Art Museums in the face of Wednesday’s breaking—and heartbreaking—news of the deadly shootings and violence against women of Asian descent in Atlanta. I want to state my own shock and horror—sentiments I know so many of you share—that once again we are confronted by a wave of racist violence that makes it impossible for so many communities in this country to feel safe. Anti-Asian hostility has a long history in the United States. … want to say emphatically that the Harvard Art Museums stand firmly against Anti-Asian racism. It feels only moments ago that I was writing to you about the murder of George Floyd and so many others and the importance of banding together in support of our black and brown communities.

(Do we think that George Floyd, with his minimal employment history, would have been a likely customer for a $20 ticket to Martha Tesdeschi’s museum? If not, what qualifies Martha Tedeschi to talk about those in Mr. Floyd’s socioeconomic stratum?)

What if we go downmarket and down the river? From L. Rafael Reif, President of MIT:

This message is for everyone. But let me begin with a word for the thousands of members of our MIT family – undergraduates, graduate students, postdocs, staff, faculty, alumni, parents and Corporation members – who are Asian or of Asian descent: We would not be MIT without you.

(But, as noted above, “we also don’t want too many of you”?)

Bizarrely, for a school that claims credentials are important enough to spend years and hundreds of thousands of dollars acquiring, the president of MIT, with no credentials in criminology or political science, claims expertise in criminology and political science:

Across the country, a cruel signature of this pandemic year has been a terrible surge in anti-Asian violence, discrimination and public rhetoric. I know some of you have experienced such harm directly. The targets are very often women and the elderly.

These acts are especially disturbing in the context of several years of mounting hostility and suspicion in the United States focused on people of Chinese origin. The murders in Georgia Tuesday, including among the victims so many Asian women, come as one more awful shock.

Lumped in with the discussion regarding spa workers, because she happened to have identified (maybe?) as an Asian female:

Earlier this month, we lost an extraordinary citizen of MIT, ChoKyun Rha ’62, SM ’64, SM ’66, SCD ’67, a professor post-tenure of biomaterials science and engineering, at the age of 87. Raised in Seoul in a family that expected her to become a doctor, she came to MIT because she wanted to be an engineer. In 1974, she joined our faculty; in 1980, she became the first Asian female faculty member to earn tenure at MIT. Dr. Rha went on to build a remarkable career as a teacher, a mentor and a scholar.

It is difficult to imagine how alone she must have felt in her early years at MIT, when women students and Asian students numbered in just dozens. But the trail she and so many others blazed helped lead to the rich diversity of MIT we treasure today.

Is this an example of “All Look Same”? In the context of killings of spa workers in Atlanta, what’s the relevance of someone who defied her family by becoming an engineer rather than a doctor and never lived in Atlanta?

(Also, Rafael Reif says that she must have felt alone (how can he know?). If so, given that she stayed at MIT for four degrees and to work as a professor, isn’t that equivalent to calling her stupid? An intelligent person would have left MIT, presumably, and gone somewhere where she didn’t feel alone.)

Circling back to the title of this post… if the presidents of Harvard and MIT love Asians so much, why won’t they let them into their respective schools?

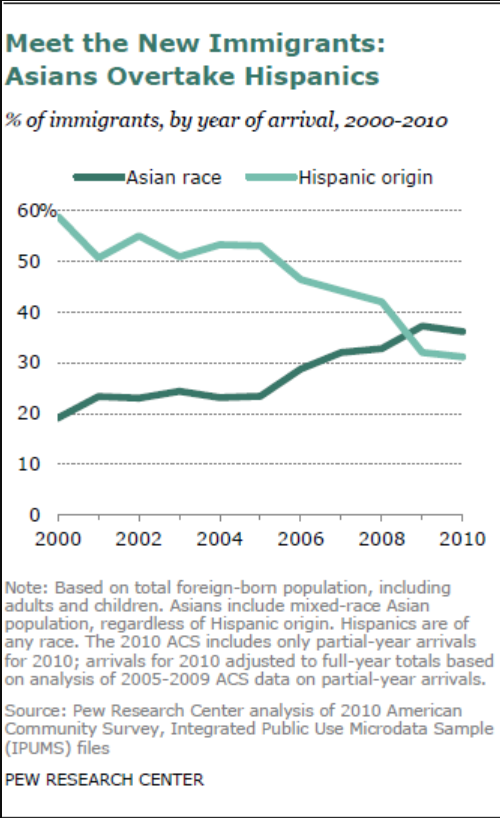

(If the answer is, “we just can’t find enough Asians whose personalities we like, notwithstanding their superb academic achievements,” here are some numbers from “The Rise of Asian Americans” (Pew, 2012): “The modern immigration wave from Asia is nearly a half century old and has pushed the total population of Asian Americans—foreign born and U.S born, adults and children—to a record 18.2 million in 2011, or 5.8% of the total U.S. population, up from less than 1% in 1965.”

)

Readers: Are you getting a lot of email from bureaucrats expressing their new-found love for Asians?

Full post, including comments